Measuring What Matters for Breast Cancer Survivors: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Croatian Version of Lymphedema Quality of Life Tool-Arm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

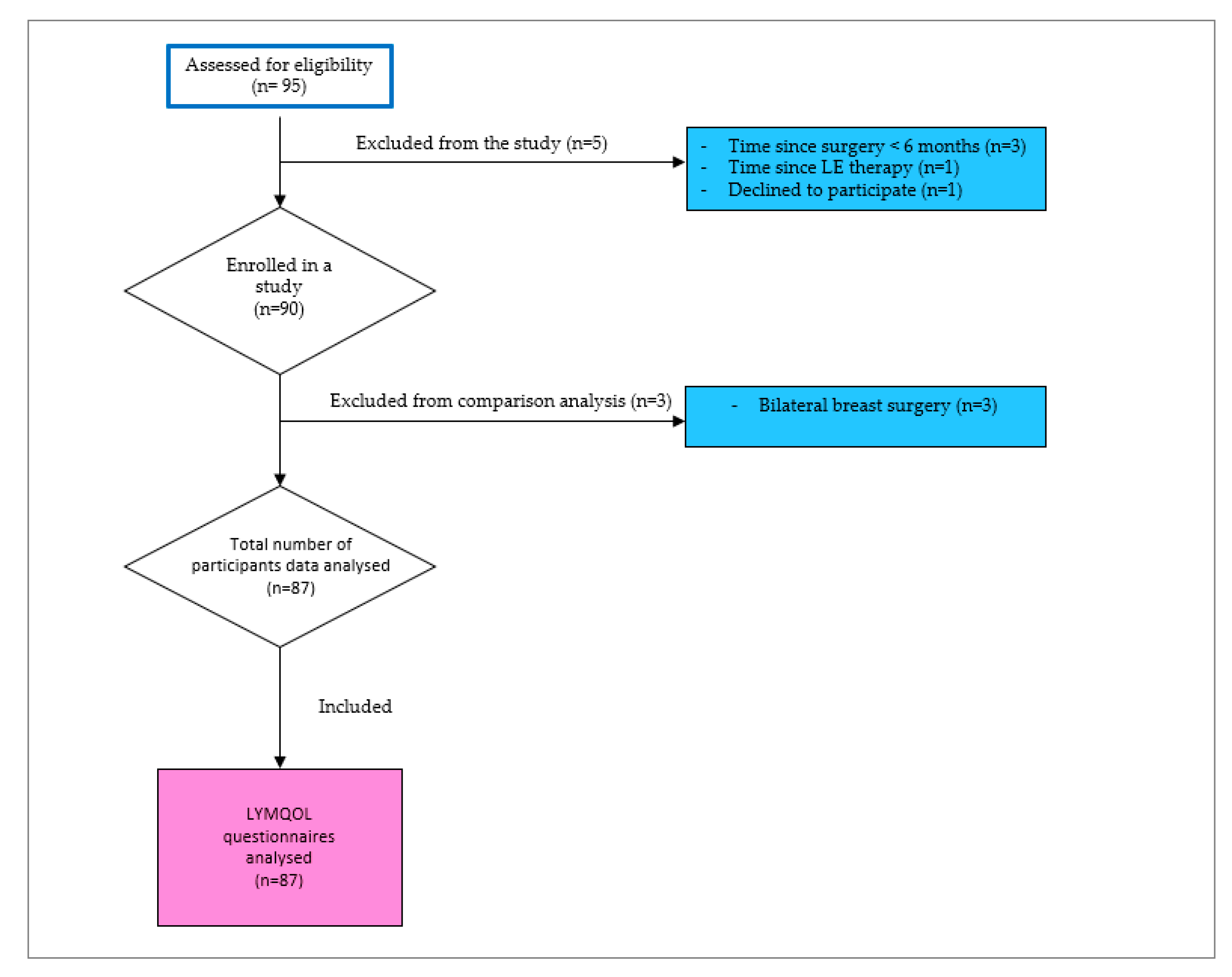

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Lymphedema Diagnosis

2.3.1. Volume Measurements of the Upper Limbs

2.3.2. Patients’ Self-Perceived Lymphedema

2.4. Instruments/Outcome Measures

2.4.1. Lymphedema Quality of Life Questionnaire-Arm (LYMQoL-Arm)

2.4.2. Short-Form Health Survey with 36 Items (SF-36)

2.4.3. Pain Intensity Numerical Rating Scale (PINRS)

2.5. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation Process

2.5.1. Forward Translation

2.5.2. Reconciliation

2.5.3. Back Translation

2.5.4. Back Translation Review and Harmonisation

2.5.5. Cognitive Debriefing

2.5.6. Review of Cognitive Debriefing Results and Finalisation

2.5.7. Proofreading and Editing

2.6. Reliability

2.6.1. Internal Consistency

2.6.2. Test–Retest Reliability

2.7. Validation

2.7.1. Content Validity

2.7.2. Criterion and Construct Validity

2.7.3. Discriminant Validity

2.8. Responsiveness

2.9. Factor Structure

2.10. Floor/Ceiling Effects

2.11. Quality of Evidence for the Measurement Properties of LYMQoL

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Translation Process

3.2. Participants’ Demographics and Treatment-Related Characteristics

3.3. Reliability

3.3.1. Internal Consistency

3.3.2. Test–Retest Reliability

3.4. Validity

3.4.1. Criterion and Construct Validity

3.4.2. Discriminant Validity

3.4.3. Content Validity

Responsiveness

3.5. Factor Analysis

3.6. Floor and Ceiling Effects

3.7. Quality of Evidence for the Measurement Properties of LYMQoL

4. Discussion

4.1. Content Validity and Cultural Adaptation

4.2. Reliability

4.3. Validity

4.4. Clinical Interpretation and Construct Relationships

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TLA | Three-letter acronyms |

| LYMQoL | Lymphedema Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| SF-36 | Short-Form Health Survey |

| PI-PINRS-11 | Pain Intensity Numerical Rating Scale |

| RVC | Relative Volume Change |

| BCRL | Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| UL | Upper Limb |

| CRO | Croatian |

| PROM | Patient Reported Outcome Measure |

| SF-36 | Short Form Health Survey—36 Items |

| PCS | Physical Component Summary |

| MCS | Mental Component Summary |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| CI | Confidence Interval; |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy; |

| LQ | LYMQoL Question |

| SD | Standard Error of Measurement |

| α | Cronbach Alpha |

| EORTC QLQ C30 | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. |

| EQ 5D | EuroQol 5-Dimensions questionnaire |

| PINRS | Numerical rating Scale |

| F | F-statistics |

| p | Probability value |

| SRD | Smallest Real Difference |

References

- Hazard-Jenkins, H.W. Breast Cancer Survivorship-Mitigating Treatment Effects on Quality of Life and Improving Survival. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 49, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel-Parra, G.A.; García-Vivar, C.; Escalada-Hernández, P.; San Martín-Rodríguez, L.; Soto-Ruiz, N. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for long-term breast cancer survivorship: Assessment of quality and evidence-based recommendations. Br. J. Cancer 2025, 133, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajoei, R.; Ilkhani, M.; Azadeh, P.; Zohari Anboohi, S.; Heshmati Nabavi, F. Breast cancer survivors-supportive care needs: Systematic review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 13, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauer, E.R.; Ganz, P.A. Moving the Translational Needle in Breast Cancer Survivorship: Connecting Intervention Research to Clinical Practice. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2069–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, R.; Magrini, N.; Penna, A.; Mura, G.; Liberati, A. Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: The need for a critical appraisal. Lancet 2000, 355, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala de la Peña, F.; Antolín Novoa, S.; Gavilá Gregori, J.; González Cortijo, L.; Henao Carrasco, F.; Martínez Martínez, M.T.; Morales Estévez, C.; Stradella, A.; Vidal Losada, M.J.; Ciruelos, E. SEOM-GEICAM-SOLTI clinical guidelines for early-stage breast cancer (2022). Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2023, 25, 2647–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biganzoli, L.C.M.; Conte, B.; Cortesi, L.; Criscitiello, C.D.M.L.; Fiorentino, A.; Levaggi, A.; Montemurro, F.; Marchio, C.; Tinterri, C.; Zambelli, A. Breast Neoplasms Guidelines; Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica: Milano, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stangl, S.; Follmann, M.; Wenzel, G.; Langer, T.; Wöckel, A. Evidence-based guideline for the early detection, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of breast cancer. In Germany: German Guideline Program in Oncology (GGPO); The Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany: Frankfurt, Germany, 2021; Volume 462. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, C.; Levenhagen, K.; Ryans, K.; Perdomo, M.; Gilchrist, L. Interventions for Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Clinical Practice Guideline from the Academy of Oncologic Physical Therapy of APTA. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, M.G.; Toyserkani, N.M.; Hansen, F.G.; Bygum, A.; Sørensen, J.A. The impact of lymphedema on health-related quality of life up to 10 years after breast cancer treatment. npj Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSipio, T.; Rye, S.; Newman, B.; Hayes, S. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földi, M. On the pathophysiology of arm lymphedema after treatment for breast cancer. Lymphology 1995, 28, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, S.A.; Brunelle, C.L.; Taghian, A. Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Risk Factors, Screening, Management, and the Impact of Locoregional Treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2341–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, L.; Garne, J.P.; Søgaard, M.; Laursen, B.S. The experience of distress in relation to surgical treatment and care for breast cancer: An interview study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappalardo, M.; Starnoni, M.; Franceschini, G.; Baccarani, A.; De Santis, G. Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Recent Updates on Diagnosis, Severity and Available Treatments. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridner, S.H.; Dietrich, M.S. Development and validation of the Lymphedema Symptom and Intensity Survey-Arm. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 3103–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, L.H.; Narkthong, N.; Hulett, J.M. Psychosocial Issues Associated with Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Literature Review. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2020, 12, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbari, A.B.; Wanchai, A.; Armer, J.M. Breast cancer-related lymphedema and quality of life: A qualitative analysis over years of survivorship. Chronic Illn. 2021, 17, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.; Lukkahatai, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Salim, N.A.; Han, G.; Qiang, W.; Lu, Q. Upper limb symptoms in breast cancer survivors with lymphedema: A latent class analysis and network analysis. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 12, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Liu, J.E.; Zhu, Y.; Mak, Y.W.; Qiu, H.; Liu, L.H.; Yang, S.S.; Chen, S.H. Development and validation of a nomogram to predict the risk of breast cancer-related lymphedema Among Chinese breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5435–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togawa, K.; Ma, H.; Smith, A.W.; Neuhouser, M.L.; George, S.M.; Baumgartner, K.B.; McTiernan, A.; Baumgartner, R.; Ballard, R.M.; Bernstein, L. Self-reported symptoms of arm lymphedema and health-related quality of life among female breast cancer survivors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormes, J.M.; Bryan, C.; Lytle, L.A.; Gross, C.R.; Ahmed, R.L.; Troxel, A.B.; Schmitz, K.H. Impact of lymphedema and arm symptoms on quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Lymphology 2010, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Dunn, M.; Plinsinga, M.L.; Reul-Hirche, H.; Ren, Y.; Laakso, E.L.; Troester, M.A. Do Patient-Reported Upper-Body Symptoms Predict Breast Cancer-Related Lymphoedema: Results from a Population-Based, Longitudinal Breast Cancer Cohort Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coriddi, M.; Dayan, J.; Sobti, N.; Nash, D.; Goldberg, J.; Klassen, A.; Pusic, A.; Mehrara, B. Systematic Review of Patient-Reported Outcomes following Surgical Treatment of Lymphedema. Cancers 2020, 12, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chima, C.; Murray, B.; Moore, Z.; Costello, M.; George, S. Health-related quality of life and assessment in patients with lower limb lymphoedema: A systematic review. J. Wound Care 2022, 31, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeley, V.; Crooks, S.; Locke, J.; Veigas, D.; Riches, K.; Hilliam, R. A quality of life measure for limb lymphoedema (LYMQOL). J. Lymphoedema 2010, 5, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Alfano, C.M.; Leach, C.R.; Smith, T.G.; Miller, K.D.; Alcaraz, K.I.; Cannady, R.S.; Wender, R.C.; Brawley, O.W. Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: A blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.R.; Axelrod, D.; Cleland, C.M.; Qiu, Z.; Guth, A.A.; Kleinman, R.; Scagliola, J.; Haber, J. Symptom report in detecting breast cancer-related lymphedema. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2015, 7, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticone, M.; Ferriero, G.; Keeley, V.; Brunati, R.; Liquori, V.; Maggioni, S.; Restelli, M.; Giordano, A.; Franchignoni, F. Lymphedema quality of life questionnaire (LYMQOL): Cross-cultural adaptation and validation in Italian women with upper limb lymphedema after breast cancer. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 4075–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilani, E.; Zanudin, A.; Mohd Nordin, N.A. Psychometric Properties of Quality of Life Questionnaires for Patients with Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2519. [Google Scholar]

- Levenhagen, K.; Davies, C.; Perdomo, M.; Ryans, K.; Gilchrist, L. Diagnosis of Upper Quadrant Lymphedema Secondary to Cancer: Clinical Practice Guideline From the Oncology Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Phys. Ther. 2017, 97, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünherz, L.; Hulla, H.; Uyulmaz, S.; Giovanoli, P.; Lindenblatt, N. Patient-reported outcomes following lymph reconstructive surgery in lower limb lymphedema: A systematic review of literature. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2021, 9, 811–819.e812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, P.; Yaman, A.; Denizli, M.; Karahan, S.; Özdemir, O. The reliability and validity of Lymphedema Quality of Life Questionnaire-Arm in Turkish patients with upper limb lymphedema related with breast cancer. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 64, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, K.E.; Yeo, S.M.; Yoo, J.S.; Hwang, J.H. Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of the Lymphedema Quality of Life Questionnaire in Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema Patients. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2023, 21, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Xiu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, J. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of lymphedema patient-reported outcome measurements in Chinese breast cancer patients [abstract]. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, PO3-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, T.; Warg, M.L.; Heister, S.; Lidzba, K.; Ciklatekerlio, G.; Molter, Y.; Langer, S.; Nuwayhid, R. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Lymphedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (LYMQOL) in German-Speaking Patients with Upper Limb Lymphedema. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Pas, C.B.; Biemans, A.A.; Boonen, R.S.; Viehoff, P.B.; Neumann, H.A. Validation of the Lymphoedema Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (LYMQOL) in Dutch Patients Diagnosed with Lymphoedema of the Lower Limbs. Phlebology 2016, 31, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.Y.; Long, X.; Yang, E.L.; Li, Y.Z.; Li, Z.J.; Xu, M.; Zhang, B.F.; Yu, N.Z.; Huang, J.Z. Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of the Lymphedema Quality of Life Questionnaire. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 2021, 36, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Jayasinghe, U.W.; Koelmeyer, L.; Ung, O.; Boyages, J. Reliability and validity of arm volume measurements for assessment of lymphedema. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryans, K.; Perdomo, M.; Davies, C.C.; Levenhagen, K.; Gilchrist, L. Rehabilitation interventions for the management of breast cancer-related lymphedema: Developing a patient-centered, evidence-based plan of care throughout survivorship. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 17, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wedin, M.; Fredrikson, M.; Ahlner, E.; Falk, A.; Sandström, Å.; Lindahl, G.; Rosenberg, P.; Kjølhede, P. Validation of the Lymphoedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (LYMQOL) in Swedish cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2020, 59, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockson, S.G. Lymphedema after Breast Cancer Treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armer, J.M.; Stewart, B.R. A comparison of four diagnostic criteria for lymphedema in a post-breast cancer population. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2005, 3, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridner, S.H.; Montgomery, L.D.; Hepworth, J.T.; Stewart, B.R.; Armer, J.M. Comparison of upper limb volume measurement techniques and arm symptoms between healthy volunteers and individuals with known lymphedema. Lymphology 2007, 40, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Deltombe, T.; Jamart, J.; Recloux, S.; Legrand, C.; Vandenbroeck, N.; Theys, S.; Hanson, P. Reliability and limits of agreement of circumferential, water displacement, and optoelectronic volumetry in the measurement of upper limb lymphedema. Lymphology 2007, 40, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.; Cornish, B.; Newman, B. Comparison of methods to diagnose lymphoedema among breast cancer survivors: 6-month follow-up. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2005, 89, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarić-Kukuz, I.; Mršić, D.B.; Matana, A.; Barun, B.; Aljinović, J.; Marinović-Guić, M.; Poljičanin, A. High-Frequency Ultrasonography Imaging: Anatomical Measuring Site as Potential Clinical Marker for Early Identification of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancukiewicz, M.; Russell, T.A.; Otoole, J.; Specht, M.; Singer, M.; Kelada, A.; Murphy, C.D.; Pogachar, J.; Gioioso, V.; Patel, M.; et al. Standardized method for quantification of developing lymphedema in patients treated for breast cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 79, 1436–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soran, A.; Ozmen, T.; McGuire, K.P.; Diego, E.J.; McAuliffe, P.F.; Bonaventura, M.; Ahrendt, G.M.; DeGore, L.; Johnson, R. The importance of detection of subclinical lymphedema for the prevention of breast cancer-related clinical lymphedema after axillary lymph node dissection; a prospective observational study. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2014, 12, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, T.W.; Fan, X.; Sparapani, R.; Laud, P.W.; Walker, A.P.; Nattinger, A.B. A contemporary, population-based study of lymphedema risk factors in older women with breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 16, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout Gergich, N.L.; Pfalzer, L.A.; McGarvey, C.; Springer, B.; Gerber, L.H.; Soballe, P. Preoperative assessment enables the early diagnosis and successful treatment of lymphedema. Cancer 2008, 112, 2809–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Specht, M.C.; Miller, C.L.; Russell, T.A.; Horick, N.; Skolny, M.N.; O’Toole, J.A.; Jammallo, L.S.; Niemierko, A.; Sadek, B.T.; Shenouda, M.N.; et al. Defining a threshold for intervention in breast cancer-related lymphedema: What level of arm volume increase predicts progression? Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 140, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerniec, S.A.; Ward, L.C.; Refshauge, K.M.; Beith, J.; Lee, M.J.; York, S.; Kilbreath, S.L. Assessment of breast cancer-related arm lymphedema--comparison of physical measurement methods and self-report. Cancer Investig. 2010, 28, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyages, J.; Vicini, F.A.; Shah, C.; Koelmeyer, L.A.; Nelms, J.A.; Ridner, S.H. The Risk of Subclinical Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema by the Extent of Axillary Surgery and Regional Node Irradiation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 109, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelle, C.L.; Roberts, S.A.; Horick, N.K.; Gillespie, T.C.; Jacobs, J.M.; Daniell, K.M.; Naoum, G.E.; Taghian, A.G. Integrating Symptoms Into the Diagnostic Criteria for Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Applying Results From a Prospective Surveillance Program. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 2186–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juresa, V.; Ivanković, D.; Vuletić, G.; Babić-Banaszak, A.; Srcek, I.; Mastilica, M.; Budak, A. The Croatian Health Survey--SF-36: I. General quality of life assessment. Coll. Antropol. 2000, 24, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Maslić Sersić, D.; Vuletić, G. Psychometric evaluation and establishing norms of Croatian SF-36 health survey: Framework for subjective health research. Croat. Med. J. 2006, 47, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar, J.T.; Young, J.P., Jr.; LaMoreaux, L.; Werth, J.L.; Poole, M.R. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001, 94, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, S.; Lončarić Kelečić, I.; Bilić, M.; Begić, M.; Pate, J.W. Conceptualization of pain in Croatian adults: A cross-sectional and psychometric study. Croat. Med. J. 2024, 65, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruchinho, P.; López-Franco, M.D.; Capelas, M.L.; Almeida, S.; Bennett, P.M.; Miranda da Silva, M.; Teixeira, G.; Nunes, E.; Lucas, P.; Gaspar, F. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of Measurement Instruments: A Practical Guideline for Novice Researchers. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 2701–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuster, J. Review: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews for interventions, Version 5.1.0, published 3/2011. Julian P.T. Higgins and Sally Green, Editors. Res. Synth. Methods 2011, 2, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.N.; Cornacchi, S.D.; Tsangaris, E.; Poulsen, L.; Beelen, L.M.; Bordeleau, L.; Zhong, T.; Jorgensen, M.G.; Sorensen, J.A.; Mehrara, B.; et al. Iterative qualitative approach to establishing content validation of a patient-reported outcome measure for arm lymphedema: The LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2024, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, Y.; Tuğral, A.; Özdemir, Ö.; Duygu, E.; Üyetürk, Ü. Translation and Validation of the Turkish Version of Lymphedema Quality of Life Tool (LYMQOL) in Patients with Breast Cancer Related Lymphedema. Eur. J. Breast Health 2017, 13, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, V.; Dovey, T.; Wade, A. Assessing Test-Retest Reliability of Psychological Measures. European Psychologist. Eur. Psychol. 2017, 22, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusic, A.; Liu, J.C.; Chen, C.M.; Cano, S.; Davidge, K.; Klassen, A.; Branski, R.; Patel, S.; Kraus, D.; Cordeiro, P.G. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures in head and neck cancer surgery. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2007, 136, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.; Cornish, B.; Newman, B. Preoperative assessment enables the early detection and successful treatment of lymphedema. Cancer 2010, 116, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgay, T.; Günel Karadeniz, P.; Maralcan, G. Quality of Life for Women with Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: The Importance of Collaboration between Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and General Surgery Clinics. Arch. Breast Cancer 2021, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulley, C.; Gaal, S.; Coutts, F.; Blyth, C.; Jack, W.; Chetty, U.; Barber, M.; Tan, C.W. Comparison of breast cancer-related lymphedema (upper limb swelling) prevalence estimated using objective and subjective criteria and relationship with quality of life. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 807569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2020 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 2020, 53, 3–19. [CrossRef]

- Paramanandam, V.S.; Lee, M.J.; Kilbreath, S.L.; Dylke, E.S. Self-reported questionnaires for lymphoedema: A systematic review of measurement properties using COSMIN framework. Acta Oncol. 2021, 60, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, J.N.; Xing, Y.; Zaniletti, I.; Askew, R.L.; Stewart, B.R.; Armer, J.M. Minimal limb volume change has a significant impact on breast cancer survivors. Lymphology 2009, 42, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, J.; Tuttle, N.; Box, R.; Reul-Hirche, H.; Laakso, E.L. Localised Objective Characterisation Assessment of Lymphoedema (LOCAL): Using High-Frequency Ultrasound, Bioelectrical Impedance Spectroscopy and Volume to Evaluate Superficial Tissue Composition. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanza, M.; Bergmann, A.; Ferreira, M.G.; de Aguiar, S.S.; Dias Rde, A.; Abrahão Kde, S.; Paltrinieri, E.M.; Allende, R.G.; de Andrade, M.F. Quality of Life and Volume Reduction in Women with Secondary Lymphoedema Related to Breast Cancer. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2015, 2015, 586827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viehoff, P.B.; van Genderen, F.R.; Wittink, H. Upper limb lymphedema 27 (ULL27): Dutch translation and validation of an illness-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire for patients with upper limb lymphedema. Lymphology 2008, 41, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bundred, N.; Foden, P.; Todd, C.; Morris, J.; Watterson, D.; Purushotham, A.; Bramley, M.; Riches, K.; Hodgkiss, T.; Evans, A.; et al. Increases in arm volume predict lymphoedema and quality of life deficits after axillary surgery: A prospective cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbestad, F.E.; Ammitzbøll, G.; Horsbøll, T.A.; Andersen, I.; Johansen, C.; Zehran, B.; Dalton, S.O. The long-term burden of a symptom cluster and association with longitudinal physical and emotional functioning in breast cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2023, 62, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, I.; Novy, D.M.; Chang, D.W.; Cox, M.G.; Fingeret, M.C. Examining pain, body image, and depressive symptoms in patients with lymphedema secondary to breast cancer. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, N.L.; Binkley, J.M.; Schmitz, K.H.; Andrews, K.; Hayes, S.C.; Campbell, K.L.; McNeely, M.L.; Soballe, P.W.; Berger, A.M.; Cheville, A.L.; et al. A prospective surveillance model for rehabilitation for women with breast cancer. Cancer 2012, 118, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Measure/Category | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | M ± SD 1 | 58.47 ± 8.95 |

| BMI 2 (kg/m2) | M ± SD | 27.74 ± 5.64 |

| Marital status n (%) | Married | 54.84% |

| Single | 18.28% | |

| Widowed | 15.05% | |

| Education level n (%) | High school diploma | 50.54% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 21.51% | |

| Primary school | 13.98% | |

| Household income n (%) | <1000 € | 38 (41.8%) |

| 1000–2000 € | 31 (34.1%) | |

| >2000 € | 16 (17.6%) | |

| Years since the BC 3 surgery | M ± SD | 6.25 ± 5.33 |

| Type of the BC surgery; n (%) | Breast conserving | 41.4% |

| Mastectomy | 58.6% | |

| Lymph node removal; n (%) | SLND 4 | 35 (40.2%) |

| ALND 5 | 52 (59.8%) | |

| Radiotherapy; n (%) | Yes | 75.9% |

| No | 24.1% | |

| Chemotherapy; n (%) | Yes | 60.9% |

| No | 39.0% |

| Variable | RVC 1 < 5% (n = 40) | RVC ≥ 5% (n = 47) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years); M ± SD | 55.3 ± 9.8 | 60.5 ± 10.9 | 0.021 * |

| BMI 2 (kg/m2); M ± SD | 26.8 ± 4.9 | 28.7 ± 5.2 | 0.084 |

| Time since surgery (years); M ± SD | 6.2 ± 4.8 | 7.9 ± 5.4 | 0.137 |

| Dominant arm affected; n (%) | 13 (33.3%) | 19 (40.4%) | 0.505 |

| Mastectomy; n (%) | 16 (41.0%) | 25 (53.2%) | 0.247 |

| ALND 3; n (%) | 19 (48.7%) | 31 (66.0%) | 0.096 |

| Therapy; n (%) | |||

| Radiotherapy; n (%) | 30 (76.9%) | 38 (80.9%) | 0.648 |

| Chemotherapy; n (%) | 25 (64.1%) | 34 (72.3%) | 0.417 |

| Endocrine therapy; n (%) | 27 (69.2%) | 35 (74.5%) | 0.573 |

| Self-reported swelling; n (%) | 21 (53.8%) | 40 (85.1%) | 0.001 ** |

| LYMQoL 1 Domain | Cronbach’s α | Cronbach’s α Retest |

|---|---|---|

| Function | 0.850 | 0.791 |

| Appearance | 0.846 | 0.855 |

| Symptoms | 0.907 | 0.901 |

| Mood | 0.748 | 0.921 |

| LYQMoL Domain | Test (M ± SD) 1 | Retest (M ± SD) | ICC 2 | p-Value | SEM 3 | SRD 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 0.71 | <0.01 | 0.38 | 1.05 |

| Appearance | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 0.68 | <0.01 | 0.45 | 1.25 |

| Symptoms | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 0.73 | <0.01 | 0.31 | 0.86 |

| Mood | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.69 | <0.01 | 0.39 | 1.08 |

| Global | 6.3 ± 2.1 | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 0.70 | <0.01 | 1.15 | 3.19 |

| LYQMoL 1 Domain | SF-36 2 PSC 3 | SF-36 MSC 4 | PINRS 5 Current | PINRS Worst |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | −0.65 * | −0.20 | 0.29 * | 0.29 * |

| Appearance | −0.30 | −0.15 | 0.22 * | 0.25 * |

| Symptoms | −0.70 * | −0.25 | 0.37 ** | 0.41 ** |

| Mood | −0.40 | −0.60 * | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| Domain | RVC 1 < 5% (n = 40) | RVC ≥ 5% (n = 47) | F-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LYQMoL 2-Arm Function | 1.23 ± 0.45 | 1.89 ± 0.52 | 4.23 | 0.016 * |

| LYQMoL-Arm Appearance | 1.57 ± 0.31 | 1.72 ± 0.41 | 1.12 | 0.331 |

| LYQMoL-Arm Symptoms | 1.95 ± 0.61 | 2.78 ± 0.67 | 5.67 | 0.004 * |

| LYQMoL-Arm Mood | 1.82 ± 0.39 | 2.45 ± 0.58 | 3.45 | 0.035 * |

| SF-36 3 PSC 4 | 42.1 ± 8.2 | 38.5 ± 7.6 | 2.98 | 0.087 |

| SF-36 MSC 5 | 48.3 ± 9.1 | 44.7 ± 8.9 | 1.75 | 0.189 |

| LYMQoL 1 Arm | Function | Appearance | Symptoms | Mood | Communality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LQ 2 1a | 0.36 | −0.19 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.45 |

| LQ1b | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.54 | 0.12 | 0.63 |

| LQ1c | 0.62 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.68 |

| LQ1d | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.62 | 0.09 | 0.67 |

| LQ1e | 0.76 | −0.02 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.60 |

| LQ1f | 0.85 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.77 |

| LQ1g | 0.38 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.65 |

| LQ1h | 0.87 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.76 |

| LQ2 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.60 |

| LQ3 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.63 |

| LQ4 | 0.12 | 0.86 | 0.23 | −0.07 | 0.82 |

| LQ5 | −0.01 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.81 |

| LQ6 | −0.04 | 0.85 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.73 |

| LQ7 | 0.06 | 0.73 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.71 |

| LQ8 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.42 |

| LQ9 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.73 | 0.14 | 0.64 |

| LQ10 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.82 | 0.12 | 0.78 |

| LQ11 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.82 | 0.13 | 0.78 |

| LQ12 | −0.04 | 0.22 | 0.79 | 0.33 | 0.81 |

| LQ13 | 0.07 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.76 |

| LQ14 | 0.12 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.55 | 0.68 |

| LQ15 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.77 | 0.73 |

| LQ16 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.73 | 0.71 |

| LQ17 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.86 | 0.79 |

| LQ18 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.72 | 0.70 |

| LQ19 | −0.07 | −0.09 | 0.16 | 0.88 | 0.82 |

| LQ20 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.30 | 0.29 |

| LYQMoL 1 domain | Floor (%) | Ceiling (%) | Floor (%) | Ceiling (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Retest | |||

| Function | 18.2 | 9.1 | 15.9 | 6.8 |

| Appearance | 12.7 | 5.4 | 9.8 | 4.1 |

| Symptoms | 8.3 | 3.9 | 6.2 | 2.7 |

| Mood | 10.6 | 4.8 | 7.5 | 3.6 |

| Measurement Property | COSMIN 1 Criteria/Requirement | LYMQoL-UL-CRO 2 Results | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content Validity | Item relevance, clarity, coverage of all aspects of the construct | All items are relevant and clear; the construct is thoroughly covered | Very good |

| Structural Validity | Factor analysis performed; KMO 3 > 0.7; significant Bartlett test | KMO 3 = 0.876; 4-factor model confirmed by EFA 4 | Very good |

| Internal Consistency | Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.70 for all domains | Function α = 0.85, Appearance α = 0.85, Symptoms α = 0.91, Mood α = 0.75 | Very good |

| Reliability (Test–Retest) | ICC 5 > 0.70 for all domains | Function ICC = 0.71, Appearance ICC = 0.68, Symptoms ICC = 0.73, Mood ICC = 0.69 (CI 6 0.61–0.78, p < 0.01). | Good |

| Measurement Error | SEM 7 and SRD 8 reported | SEM (Function: 0.38, Appearance: 0.45, Symptoms: 0.31, Mood: 0.39, Global: 1.15); SRD (Function: 1.05, Appearance: 1.25, Symptoms: 0.86, Mood: 1.08, Global: 3.19) | Adequate |

| Criterion Validity | Strong correlations with gold standards (SF-36 9 PCS 10, MCS 11, PINRS 12) | Function r = −0.65 (p < 0.001), Symptoms r = −0.70 (p < 0.001) with SF-36 PCS; Mood r = −0.60 (p < 0.001) with SF-36 MCS; correlations with PINRS ranged from 0.22 to 0.41 (p < 0.05) for all domains except Mood | Very good |

| Construct Validity | Correlations with related constructs | Confirmed by Spearman’s rank correlations with SF-36 PCS, MCS, and PINRS | Very good |

| Discriminant Validity | Differentiation between clinical and subclinical lymphedema | Significant differences in Function (F = 4.23, p = 0.016), Symptoms (F = 5.67, p = 0.004), Mood (F = 3.45, p = 0.035) domains | Very good |

| Responsiveness | Usability, completion time, floor and ceiling effects | Mean completion time approx. 5 min; floor effects 6.2–18.2%; ceiling effects 2.7–9.1% across domains | Very good |

| Cross-Cultural Validity | Equivalence of forward/back translation and adaptation | Near-complete equivalence, with minor linguistic adjustments | Very good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Klarić-Kukuz, I.; Ćurković, A.; Grančić, J.; Aljinović, J.; Barun, B.; Pivalica, D.; Poljičanin, A. Measuring What Matters for Breast Cancer Survivors: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Croatian Version of Lymphedema Quality of Life Tool-Arm. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020465

Klarić-Kukuz I, Ćurković A, Grančić J, Aljinović J, Barun B, Pivalica D, Poljičanin A. Measuring What Matters for Breast Cancer Survivors: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Croatian Version of Lymphedema Quality of Life Tool-Arm. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020465

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlarić-Kukuz, Ivana, Ana Ćurković, Josipa Grančić, Jure Aljinović, Blaž Barun, Dinko Pivalica, and Ana Poljičanin. 2026. "Measuring What Matters for Breast Cancer Survivors: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Croatian Version of Lymphedema Quality of Life Tool-Arm" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020465

APA StyleKlarić-Kukuz, I., Ćurković, A., Grančić, J., Aljinović, J., Barun, B., Pivalica, D., & Poljičanin, A. (2026). Measuring What Matters for Breast Cancer Survivors: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Croatian Version of Lymphedema Quality of Life Tool-Arm. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020465