Modeling the Posture–Movement Continuum: Predictive Mapping of Spinopelvic Control Across Gait Speeds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.2.1. Static Parameters

2.2.2. Dynamic Parameters

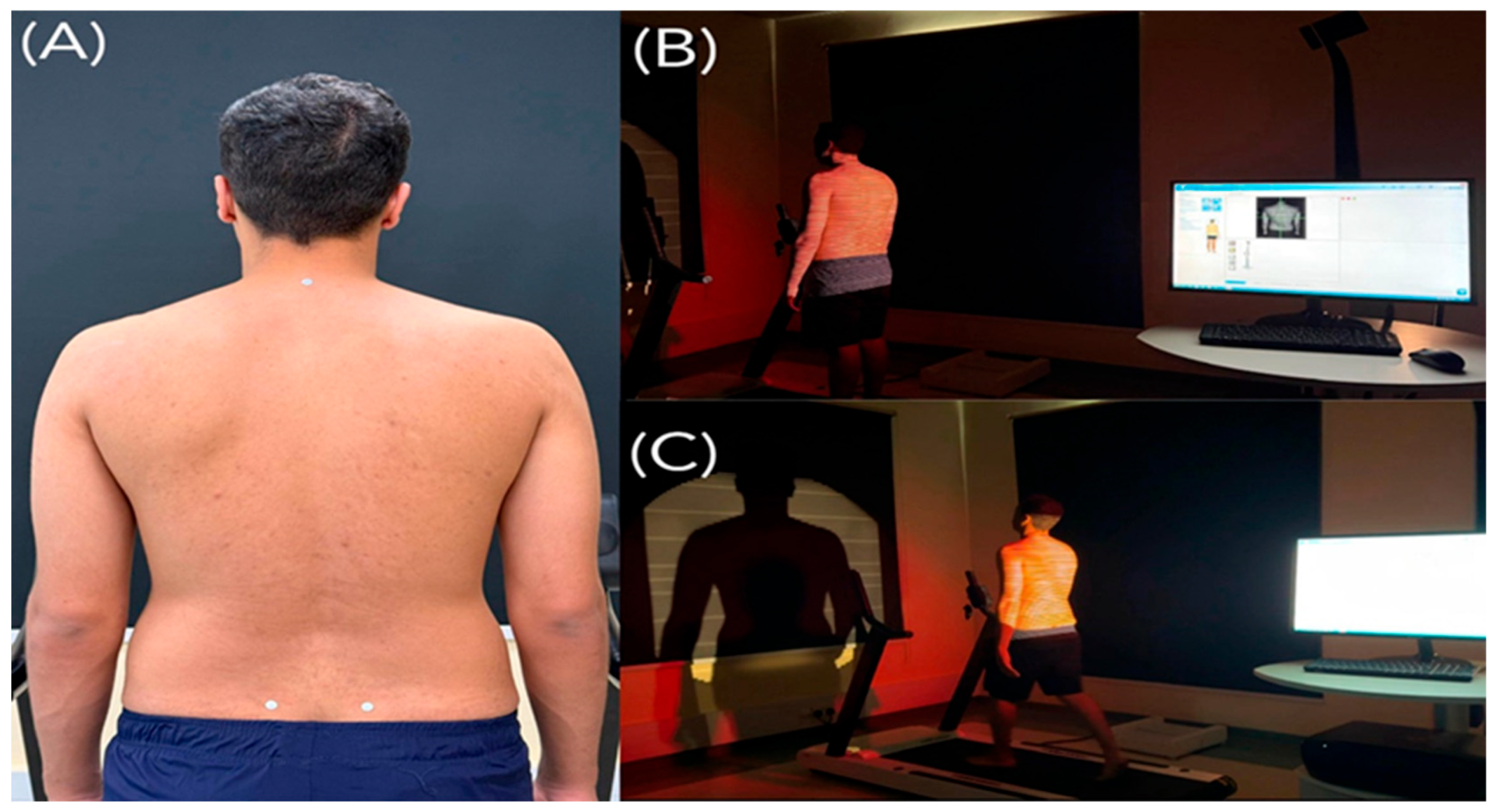

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Participant Preparation

2.3.2. CVA and Q-Angle Assessment

2.3.3. Static Spinopelvic Assessment

2.3.4. Dynamic Spinopelvic Assessment

2.4. Sample Size Determination

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

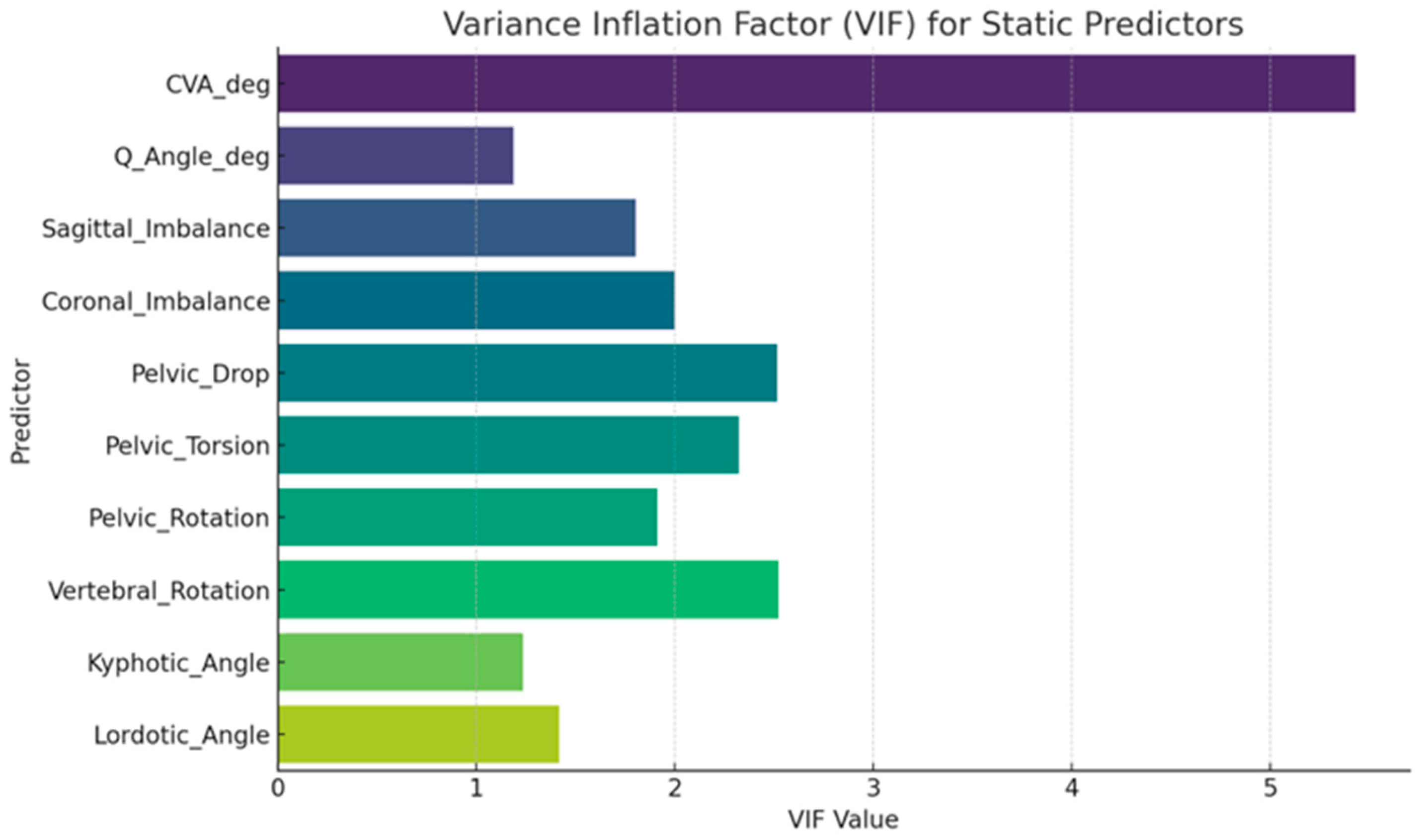

3.2. Model Diagnostics and Collinearity

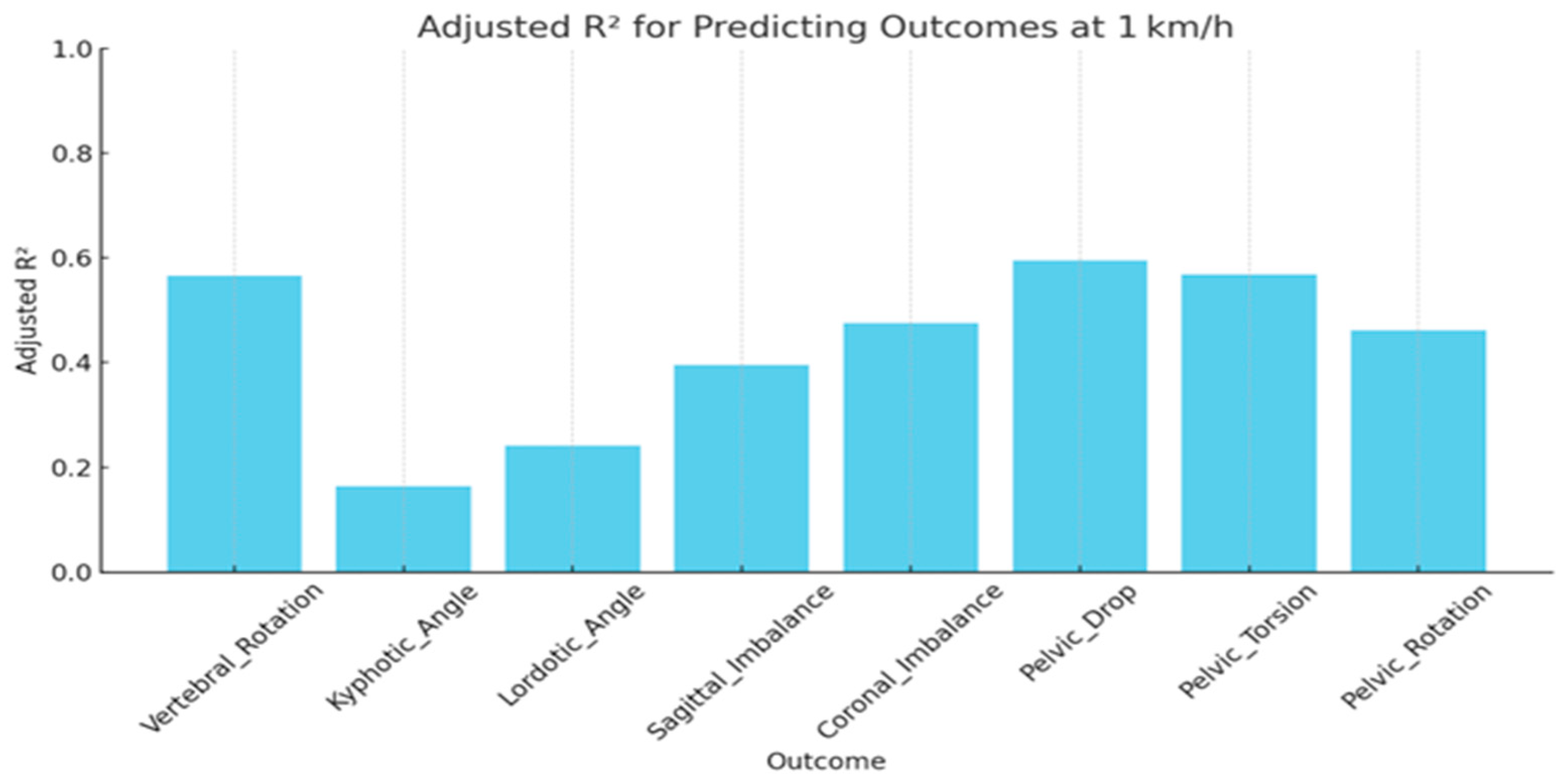

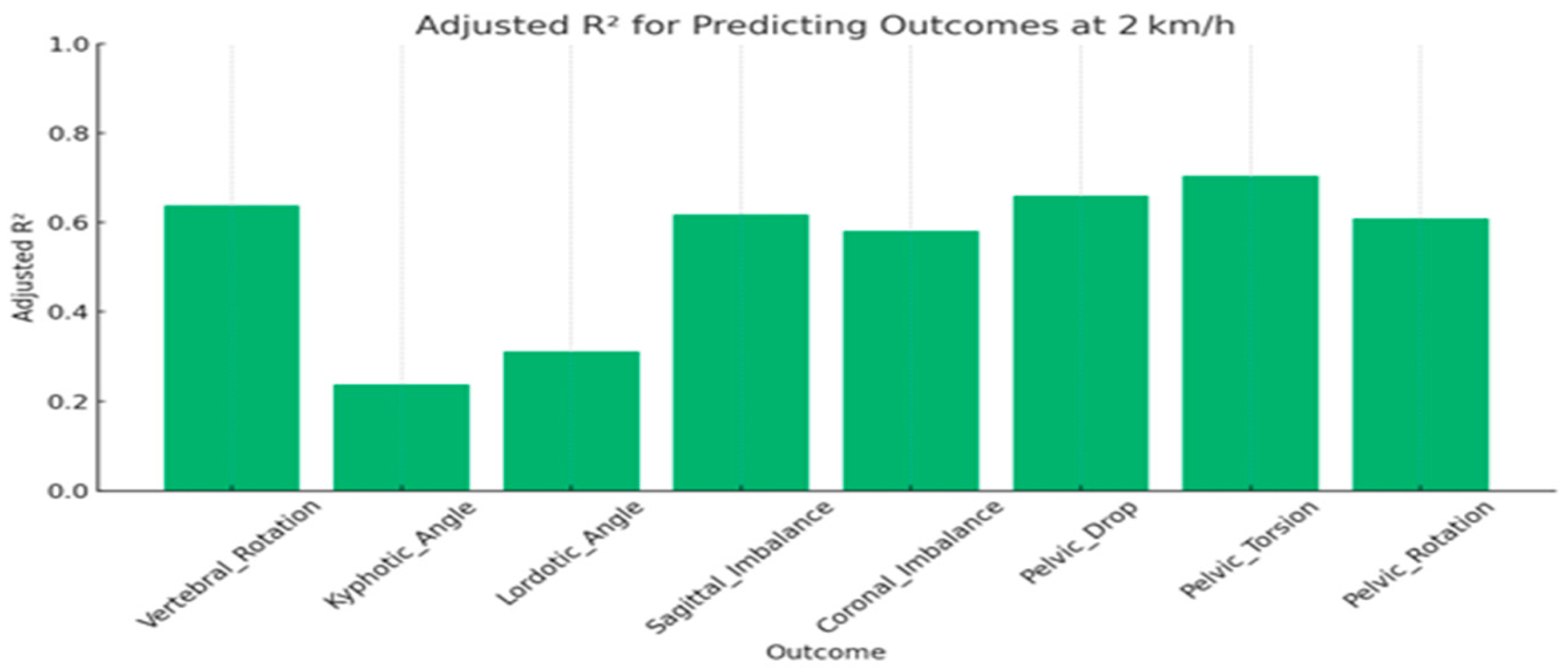

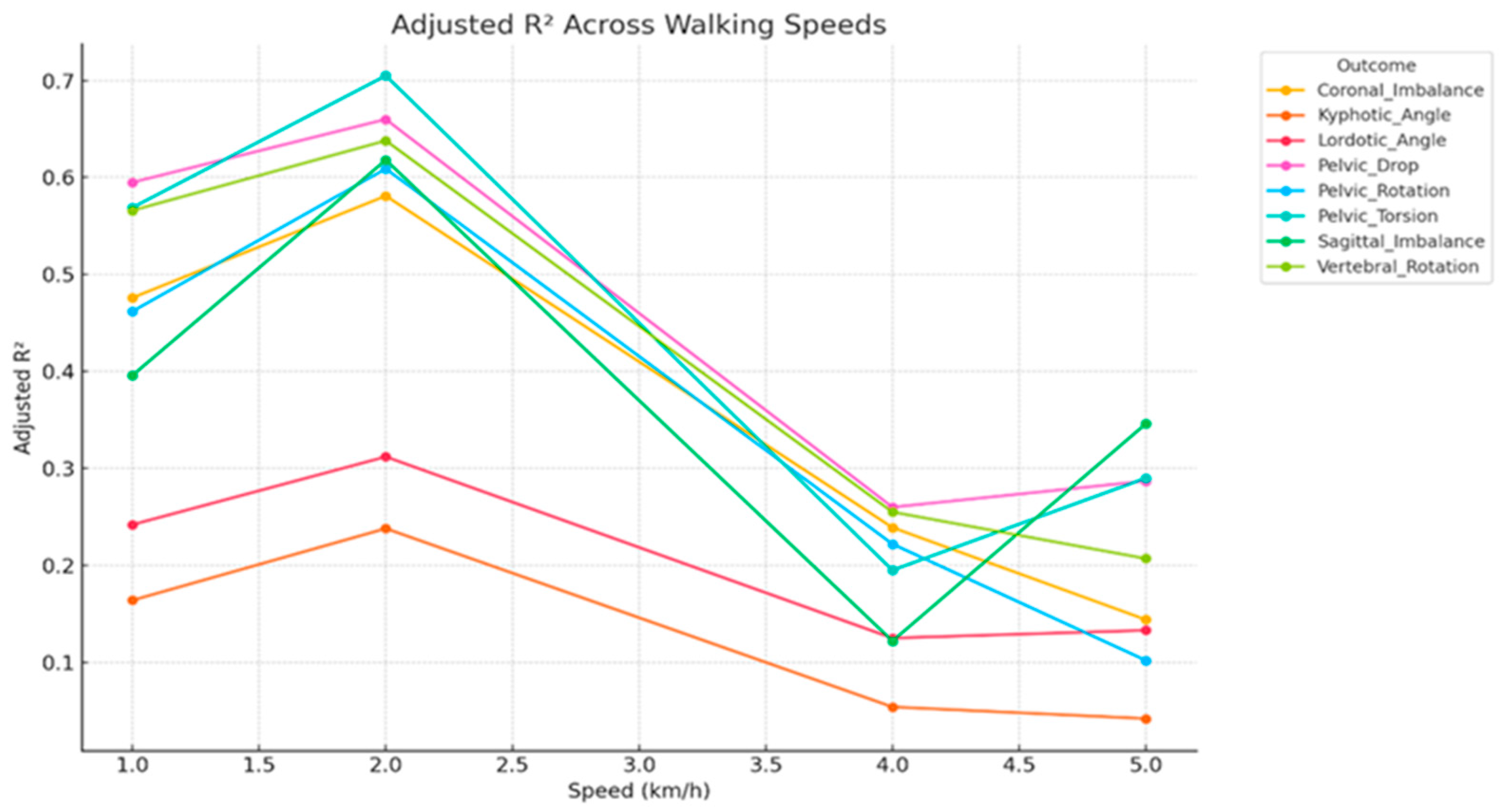

3.3. Speed-Stratified Prediction (Multiple Linear Regression)

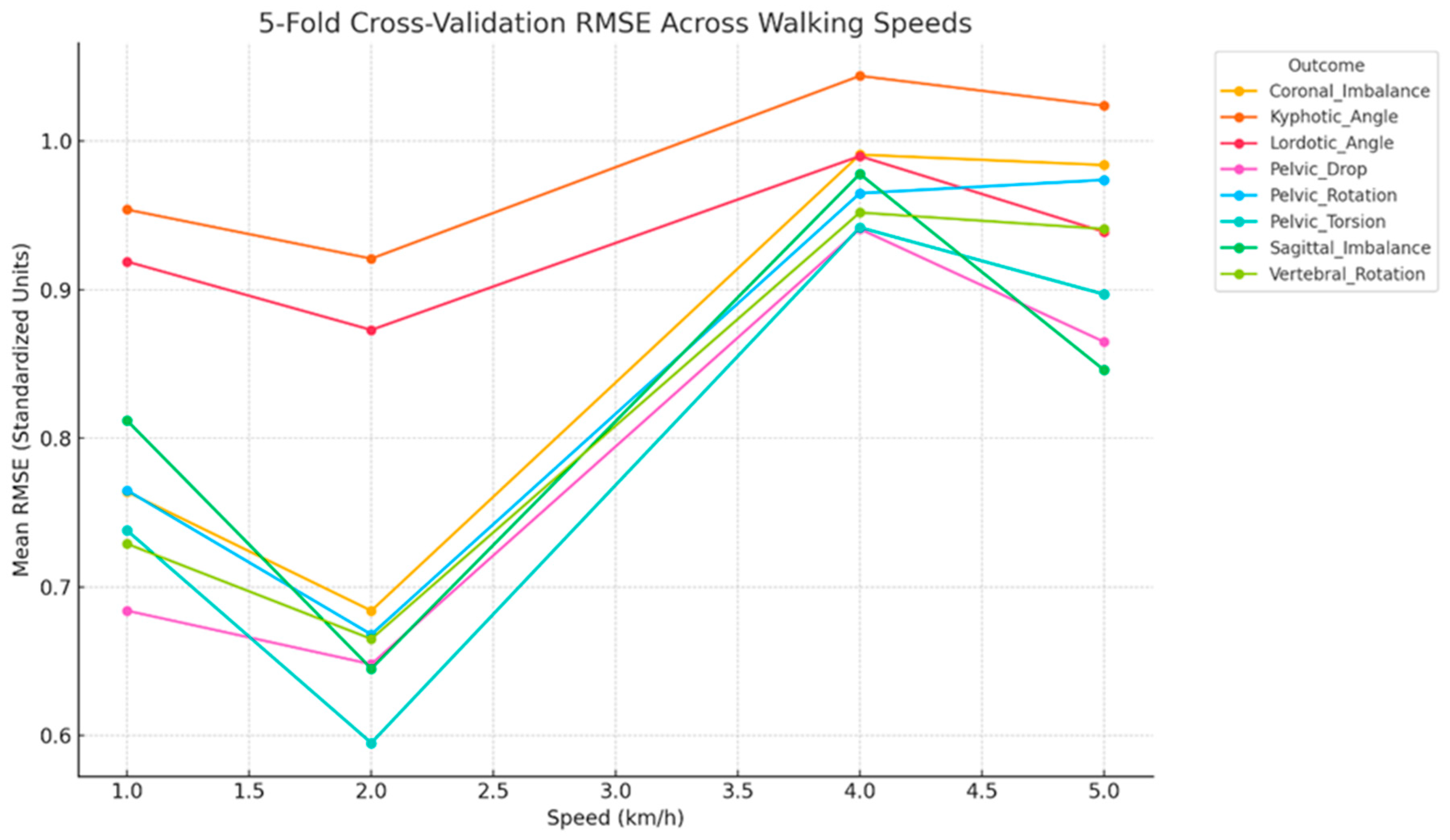

3.4. Cross-Validated Performance

3.5. Summary of Key Predictors Across Outcomes and Walking Speeds

4. Discussion

4.1. Biomechanical Role of Key Static Predictors

4.2. Transition to Neuromuscular Control at Higher Speeds

4.3. Neural Integration: Cervical Inputs and Pelvic Coupling

4.4. Clinical Implications and Functional Applications

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVA | Craniovertebral Angle |

| FHP | Forward head posture |

| Q-angle | Quadriceps angle |

References

- Abelin-Genevois, K. Sagittal Balance of the Spine. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2021, 107, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, T.; Zoroofchi, S.; Vettorazzi, E.; Droste, J.N.; Welsch, G.H.; Schwesig, R.; Marshall, R.P. Functional Analysis of Postural Spinal and Pelvic Parameters Using Static and Dynamic Spinometry. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmazer Kayatekin, A.Z.; Taşkinalp, O.; Uluçam, E. The Effect of the Quadriceps Angle on the Gait Pattern in Young Adults Aged 18–25 Years. Namık Kemal Med. J. 2025, 13, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Park, R.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Yoon, S.R.; Jung, K.I. The Effect of the Forward Head Posture on Postural Balance in Long Time Computer Based Worker. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 36, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liu, W. Does Spinal Sagittal Imbalance Lead to Future Vertebral Compression Fractures in Osteoporosis Patients? Spine J. 2021, 21, 1362–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Bhat, S.G.; Cheng, C.-H.; Pignolo, R.J.; Lu, L.; Kaufman, K.R. Age-Related Changes in Gait, Balance, and Strength Parameters: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Kadone, H.; Asada, T.; Sakashita, K.; Sunami, T.; Koda, M.; Funayama, T.; Takahashi, H.; Noguchi, H.; Sato, K.; et al. Evaluation of Dynamic Spinal Alignment Changes and Compensation Using Three-Dimensional Gait Motion Analysis for Dropped Head Syndrome. Spine J. 2022, 22, 1974–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segi, N.; Nakashima, H.; Ito, S.; Ouchida, J.; Kayamoto, A.; Oishi, R.; Yamauchi, I.; Takegami, Y.; Ishizuka, S.; Seki, T.; et al. Is Spinopelvic Compensation Associated with Unstable Gait?: Analysis Using Whole Spine X-Rays and a Two-Point Accelerometer during Gait in Healthy Adults. Gait Posture 2024, 111, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Rider, S.M.; Lafage, R.; Gupta, S.; Farooqi, A.S.; Protopsaltis, T.S.; Passias, P.G.; Smith, J.S.; Lafage, V.; Kim, H.-J.; et al. Spinopelvic Sagittal Compensation in Adult Cervical Deformity. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2023, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Salahzadeh, Z.; Karimipour, B.; Reza Azghani, M.; Sarbakhsh, P.; Adigozali, H.; Khalilian-Ekrami, N.; Hemmati, A. Postural Analysis of The Trunk, Pelvic Girdle and Lower Extremities in The Sagittal Plane in People with and without Forward Head Posture. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2022, 12, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Huec, J.C.; Thompson, W.; Mohsinaly, Y.; Barrey, C.; Faundez, A. Sagittal Balance of the Spine. Eur. Spine J. 2019, 28, 1889–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, Z.; Bhati, P.; Hussain, M.E. Influence of Forward Head Posture on Cervicocephalic Kinesthesia and Electromyographic Activity of Neck Musculature in Asymptomatic Individuals. J. Chiropr. Med. 2020, 19, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.-Y.; Lee, H.-Y.; Yong, M.-S. Characteristics of Cervical Position Sense in Subjects with Forward Head Posture. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2014, 26, 1741–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, I.; Youssef, A.S.A.; Ahbouch, A.; Harrison, D. Demonstration of Autonomic Nervous Function and Cervical Sensorimotor Control after Cervical Lordosis Rehabilitation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Athl. Train. 2021, 56, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Diab, A.A.M.; Harrison, D.E. Does Forward Head Posture Influence Somatosensory Evoked Potentials and Somatosensory Processing in Asymptomatic Young Adults? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Shousha, T.; Arumugam, A.; Harrison, D.E. Is Thoracic Kyphosis Relevant to Pain, Autonomic Nervous System Function, Disability, and Cervical Sensorimotor Control in Patients with Chronic Nonspecific Neck Pain? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijspeert, A.J.; Daley, M.A. Integration of Feedforward and Feedback Control in the Neuromechanics of Vertebrate Locomotion: A Review of Experimental, Simulation and Robotic Studies. J. Exp. Biol. 2023, 226, jeb245784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, A.D. The Relative Roles of Feedforward and Feedback in the Control of Rhythmic Movements. Mot. Control 2002, 6, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Fekete, G.; Mei, Q.; Gu, Y. The Effect of Walking Speed on the Foot Inter-Segment Kinematics, Ground Reaction Forces and Lower Limb Joint Moments. PeerJ 2018, 2018, e5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Hou, B.Y.; Lam, W.K. Influence of Gait Speeds on Contact Forces of Lower Limbs. J. Healthc. Eng. 2017, 2017, 6375976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zhao, X.; Tao, Z.; Wang, W. Gait Biomechanics and Postural Adaptations in Forward Head Posture: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, N.E.; Newsome, S.D.; Eloyan, A.; Marasigan, R.E.R.; Calabresi, P.A.; Zackowski, K.M. Longitudinal Relationships among Posturography and Gait Measures in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 2015, 84, 2048–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacRae, C.S.; Critchley, D.; Lewis, J.S.; Shortland, A. Comparison of Standing Postural Control and Gait Parameters in People with and without Chronic Low Back Pain: A Cross-Sectional Case-Control Study. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendershot, B.D.; Shojaei, I.; Acasio, J.C.; Dearth, C.L.; Bazrgari, B. Walking Speed Differentially Alters Spinal Loads in Persons with Traumatic Lower Limb Amputation. J. Biomech. 2018, 70, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otayek, J.; Bizdikian, A.J.; Yared, F.; Saad, E.; Bakouny, Z.; Massaad, A.; Ghanimeh, J.; Labaki, C.; Skalli, W.; Ghanem, I.; et al. Influence of Spino-Pelvic and Postural Alignment Parameters on Gait Kinematics. Gait Posture 2020, 76, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarwani, M.; VanSwearingen, J.M.; Perera, S.; Sparto, P.J.; Brach, J.S. Challenging the Motor Control of Walking: Gait Variability during Slower and Faster Pace Walking Conditions in Younger and Older Adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 66, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Anderschitz, M.; Dietz, V. Contribution of Feedback and Feedforward Strategies to Locomotor Adaptations. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 95, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabd, A.M.; Elabd, O.M. Relationships between Forward Head Posture and Lumbopelvic Sagittal Alignment in Older Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2021, 28, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koura, G.; Elshiwi, A.M.F.; Reddy, R.S.; Alrawaili, S.M.; Ali, Z.A.; Alshahrani, M.A.N.; Alshahri, A.A.M.; Al-Ammari, S.S.Z. Proprioceptive Deficits and Postural Instability in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Comparative Study of Balance Control and Key Predictors. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1595125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Yang, J.; Hao, Z.; Li, Y.; Fu, R.; Zu, Y.; Ma, J.; Lo, W.L.A.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, G.; et al. The Effects of Proprioceptive Weighting Changes on Posture Control in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1144900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, M.; Wild, M.; Jungbluth, P.; Hakimi, M.; Windolf, J.; Haex, B.; Horstmann, T.; Rapp, W. Reliability and Validity of 4D Rasterstereography under Dynamic Conditions. Comput. Biol. Med. 2011, 41, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalik, R.; Hamm, J.; Quack, V.; Eschweiler, J.; Gatz, M.; Betsch, M. Dynamic Spinal Posture and Pelvic Position Analysis Using a Rasterstereographic Device. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, G.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Wilkinson, T. The Relationship between Forward Head Posture, Postural Control and Gait: A Systematic Review. Gait Posture 2022, 98, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, M.G.; Hall, T.L. Quadriceps Femoris Muscle Angle: Normal Values and Relationships with Gender and Selected Skeletal Measures. Phys. Ther. 1989, 69, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szucs, K.A.; Donoso Brown, V. Rater Reliability and Construct Validity of a Mobile Application for Posture Analysis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohokum, M.; Schülein, S.; Skwara, A. The Validity of Rasterstereography: A Systematic Review. Orthop. Rev. 2015, 7, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, H.M.; Sanchez, E.G.d.M.; Baraúna, M.A.; Canto, R.S.d.T. Evaluation of Q Angle in Differents Static Postures. Acta Ortop. Bras. 2014, 22, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranjape, S.; Singhania, N. Effect of Body Positions on Quadriceps Angle Measurement. Sci. Med. J. 2019, 1, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, S.; Dullien, S.; Grifka, J.; Jansen, P. Comparison between Rasterstereographic Scan and Orthopedic Examination for Posture Assessment: An Observational Study. Front. Surg. 2024, 11, 1461569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, M.S.; Lee, H.Y. Does Forward Head Posture Influence Muscle Tone, Stiffness, and Elasticity in University Students? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dass, B.; Shinde, D.; Kala, S.; Agrawal, N. Improvement in the Lumbo-Pelvic Rhythm by the Correction of Forward Head Posture. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2020, 10, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C.L.; Laudicina, N.M.; Khuu, A.; Loverro, K.L. The Human Pelvis: Variation in Structure and Function During Gait. Anat. Rec. 2017, 300, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donati, D.; Giorgi, F.; Farì, G.; Tarallo, L.; Catani, F.; Tedeschi, R. The Influence of Pelvic Tilt and Femoral Torsion on Hip Biomechanics: Implications for Clinical Assessment and Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Huec, J.C.; Saddiki, R.; Franke, J.; Rigal, J.; Aunoble, S. Equilibrium of the Human Body and the Gravity Line: The Basics. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skouras, A.Z.; Kanellopoulos, A.K.; Stasi, S.; Triantafyllou, A.; Koulouvaris, P.; Papagiannis, G.; Papathanasiou, G. Clinical Significance of the Static and Dynamic Q-Angle. Cureus 2022, 14, e24911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, V. Proprioception and Locomotor Disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D. Human Balance and Posture Control during Standing and Walking. Gait Posture 1995, 3, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanenko, Y.P.; Grasso, R.; Zago, M.; Molinari, M.; Scivoletto, G.; Castellano, V.; Macellari, V.; Lacquaniti, F. Temporal Components of the Motor Patterns Expressed by the Human Spinal Cord Reflect Foot Kinematics. J. Neurophysiol. 2003, 90, 3555–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuchi, C.A.; Fukuchi, R.K.; Duarte, M. Effects of Walking Speed on Gait Biomechanics in Healthy Participants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay-Lyons, M. Central Pattern Generation of Locomotion: A Review of the Evidence. Phys. Ther. 2002, 82, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, S.A.; Granata, K.P. The Influence of Gait Speed on Local Dynamic Stability of Walking. Gait Posture 2007, 25, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rix, G.D.; Bagust, J. Cervicocephalic Kinesthetic Sensibility in Patients with Chronic, Nontraumatic Cervical Spine Pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 82, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treleaven, J. Sensorimotor Disturbances in Neck Disorders Affecting Postural Stability, Head and Eye Movement Control. Man. Ther. 2008, 13, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadat, M.; Salehi, R.; Negahban, H.; Shaterzadeh, M.J.; Mehravar, M.; Hessam, M. Postural Stability in Patients with Non-Specific Chronic Neck Pain: A Comparative Study with Healthy People. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2018, 32, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidary, Z.; Pirayeh, N.; Mehravar, M.; Shaterzadeh Yazdi, M.J. Evaluating the Stability Limits Between Individuals with Mild and Moderate-to-Severe Grades of Forward Head Posture. Middle East J. Rehabil. Health Stud. 2024, 11, e144970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.L.S.; Ribeiro, D.M.; Fernandes, L.C.; de Menezes, R.L. Postural Changes versus Balance Control and Falls in Community-Living Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Fisioter. Em Mov. 2018, 31, e003125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H. Effects of Forward Head Posture on Static and Dynamic Balance Control. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyeon, D.A.; Kim, J.S.; Lim, H.W. Effects of Capital Flexion Exercise on Craniovertebral Angle, Trunk Control, Balance, and Gait in Stroke Patients with Forward Head Posture: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Medicina 2025, 61, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.G.; Levin, M.F.; Garofolini, A.; Piscitelli, D.; Zhang, L. Central Pattern Generator and Human Locomotion in the Context of Referent Control of Motor Actions. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 2870–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takakusaki, K. Functional Neuroanatomy for Posture and Gait Control. J. Mov. Disord. 2017, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wah, S.W.; Puntumetakul, R.; Boucaut, R. Effects of Proprioceptive and Craniocervical Flexor Training on Static Balance in University Student Smartphone Users with Balance Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pain Res. 2021, 14, 1935–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Definitions and Interpretations |

|---|---|

| (A) Sagittal Imbalance | The vertical difference in height between the vertebra prominens (VP) and the midpoint between the left and right posterior superior iliac spines (dimple middle, DM) in the sagittal plane. |

| (B) Coronal Imbalance | The lateral deviation of the VP from the DM. A positive value indicates a shift in the VP to the right, while a negative value indicates a shift to the left. |

| (C) Kyphotic Angle | The maximum kyphotic angle measured between the surface tangents at the upper inflection point (near the VP) and the thoracolumbar inflection point. |

| (D) Lordotic Angle | The maximum lordotic angle measured between the surface tangents at the thoracolumbar inflection point and the lumbosacral inflection point. |

| (E) Vertebral Rotation | The root mean square (RMS) of the horizontal components of the surface normals along the spinal symmetry line. |

| (F) Pelvic Obliquity | The vertical difference in height between the left and right lumbar dimples. |

| (G) Pelvic Torsion | The torsional rotation difference between the surface normals at the two lumbar dimples. |

| (H) Pelvic Rotation | The horizontal rotation of the right dimple (DR) relative to the left dimple (DL), based on a frontal plane passing through the DL. |

| (I) Pelvic Tilt (drop) | The difference in height of the lumbar dimples based on horizontal plane. DR is higher than DL if the angle is positive. |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21.6 | 2.4 | 18 | 27 |

| Height (cm) | 168.4 | 7.9 | 154 | 189 |

| Weight (kg) | 65.3 | 10.8 | 46 | 94 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.9 | 3.0 | 18.3 | 30.7 |

| Gender, n (%) | Female: 58 (58%) Male: 42 (42%) | - | - | - |

| Self-reported physical activity (IPAQ categories) | - | - | - | |

| 15 (15%) | - | - | - |

| 67 (67%) | - | - | - |

| 18 (18%) | - | - | - |

| Occupation | ||||

| 90 (90%) | - | - | - |

| 4 (4%) | - | - | - |

| 6 (6%) | - | - | - |

| CVA (°) | 51.23 | 6.50 | 40.66 | 61.38 |

| Q-Angle (°) | 14.83 | 3.34 | 7.09 | 23.24 |

| Sagittal Imbalance0 (mm) | 3.93 | 0.97 | 1.68 | 6.02 |

| Coronal Imbalance0 (mm) | 5.52 | 1.16 | 2.95 | 8.27 |

| Pelvic Drop0 (°) | 3.25 | 1.03 | 1.16 | 5.37 |

| Pelvic Torsion0 (°) | 3.39 | 0.88 | 1.83 | 5.53 |

| Pelvic Rotation0 (°) | 4.29 | 1.08 | 1.76 | 6.81 |

| Vertebral Rotation0 (°) | 5.27 | 1.15 | 2.60 | 7.93 |

| Kyphotic Angle0 (°) | 56.73 | 2.80 | 50.97 | 64.10 |

| Lordotic Angle0 (°) | 42.91 | 2.72 | 36.46 | 49.10 |

| Sagittal Imbalance (mm) | 9.18 | 5.09 | 1.80 | 19.96 |

| Coronal Imbalance (mm) | 13.23 | 7.31 | 3.16 | 27.35 |

| Pelvic Drop (°) | 9.56 | 6.03 | 1.24 | 21.80 |

| Pelvic Torsion (°) | 8.61 | 5.03 | 1.90 | 19.99 |

| Pelvic Rotation (°) | 10.56 | 5.89 | 2.02 | 23.82 |

| Vertebral Rotation (°) | 11.48 | 5.95 | 2.82 | 24.86 |

| Kyphotic Angle (°) | 58.45 | 3.92 | 50.51 | 70.12 |

| Lordotic Angle (°) | 43.63 | 3.34 | 35.33 | 54.05 |

| Outcome | Adjusted R2 | MAE | RMSE | F-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral Rotation | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 15.32 | <0.001 |

| Coronal Imbalance | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 11.01 | <0.001 |

| Sagittal Imbalance | 0.40 | 0.58 | 0.74 | 8.22 | <0.001 |

| Lordotic Angle | 0.24 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 4.52 | <0.001 |

| Kyphotic Angle | 0.16 | 0.69 | 0.87 | 3.17 | 0.002 |

| Outcome | Adjusted RÂ2 | MAE | RMSE | F-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral_Rotation | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 20.35 | <0.001 |

| Kyphotic_Angle | 0.24 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 4.44 | <0.001 |

| Lordotic_Angle | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 5.98 | <0.001 |

| Sagittal_Imbalance | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 18.79 | <0.001 |

| Coronal_Imbalance | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 16.24 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic_Drop | 0.66 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 22.35 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic_Torsion | 0.71 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 27.29 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic_Rotation | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 18.12 | <0.001 |

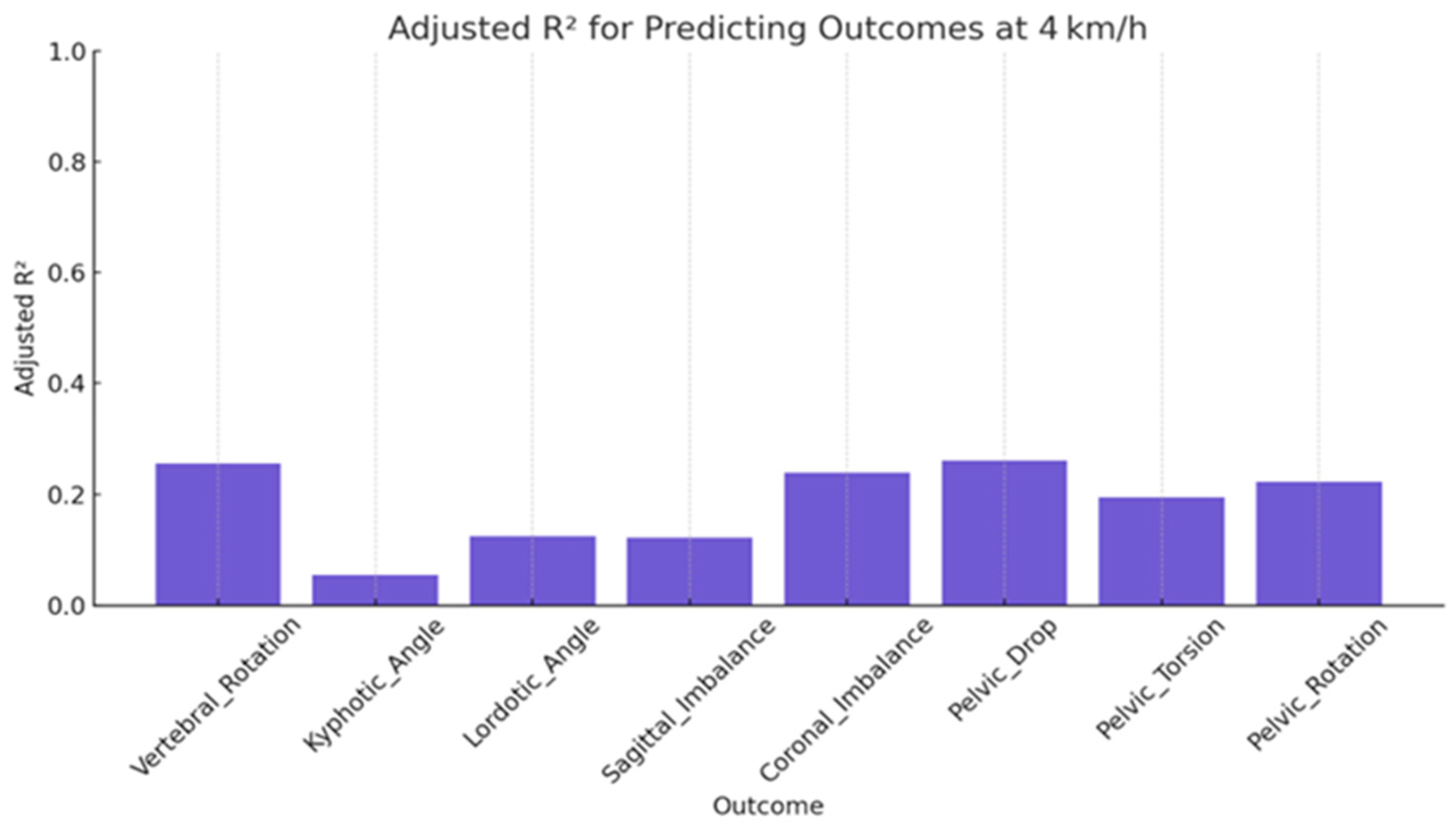

| Outcome | Adjusted RÂ2 | MAE | RMSE | F-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral_Rotation | 0.26 | 0.67 | 0.82 | 4.77 | <0.001 |

| Kyphotic_Angle | 0.05 | 0.75 | 0.93 | 1.63 | 0.118 |

| Lordotic_Angle | 0.13 | 0.73 | 0.89 | 2.56 | 0.011 |

| Sagittal_Imbalance | 0.12 | 0.72 | 0.89 | 2.53 | 0.012 |

| Coronal_Imbalance | 0.24 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 4.45 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic_Drop | 0.26 | 0.64 | 0.82 | 4.87 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic_Torsion | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 3.66 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic_Rotation | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 4.15 | <0.001 |

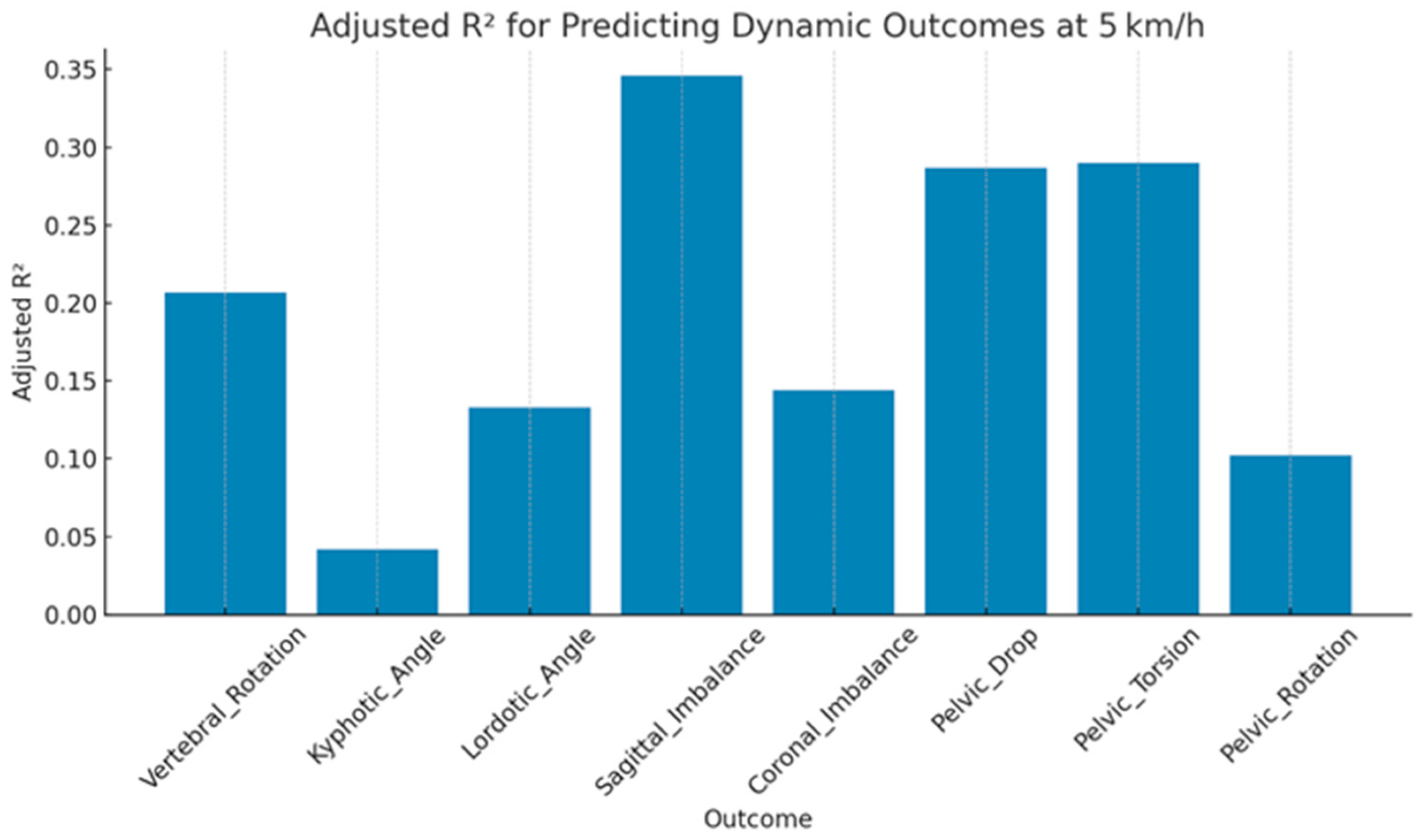

| Outcome | Adjusted RÂ2 | MAE | RMSE | F-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral_Rotation | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 3.88 | <0.001 |

| Kyphotic_Angle | 0.04 | 0.75 | 0.93 | 1.48 | 0.166 |

| Lordotic_Angle | 0.13 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 2.69 | 0.008 |

| Sagittal_Imbalance | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.77 | 6.81 | <0.001 |

| Coronal_Imbalance | 0.14 | 0.72 | 0.88 | 2.86 | 0.005 |

| Pelvic_Drop | 0.29 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 5.43 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic_Torsion | 0.29 | 0.63 | 0.80 | 5.49 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic_Rotation | 0.10 | 0.71 | 0.90 | 2.25 | 0.025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Elsayed, R.M.; Moustafa, I.M.; Alrahoomi, A.; Aldaihan, M.M.; Alsubiheen, A.M.; Khowailed, I.A. Modeling the Posture–Movement Continuum: Predictive Mapping of Spinopelvic Control Across Gait Speeds. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010073

Elsayed RM, Moustafa IM, Alrahoomi A, Aldaihan MM, Alsubiheen AM, Khowailed IA. Modeling the Posture–Movement Continuum: Predictive Mapping of Spinopelvic Control Across Gait Speeds. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleElsayed, Rofaida Mohamed, Ibrahim M. Moustafa, Abdulla Alrahoomi, Mishal M. Aldaihan, Abdulrahman M. Alsubiheen, and Iman Akef Khowailed. 2026. "Modeling the Posture–Movement Continuum: Predictive Mapping of Spinopelvic Control Across Gait Speeds" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010073

APA StyleElsayed, R. M., Moustafa, I. M., Alrahoomi, A., Aldaihan, M. M., Alsubiheen, A. M., & Khowailed, I. A. (2026). Modeling the Posture–Movement Continuum: Predictive Mapping of Spinopelvic Control Across Gait Speeds. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010073