Effects of Perceptual Learning Through Binocular Virtual Reality Exercises on Low Stereopsis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Clinical Protocol

2.2.1. Clinical Evaluation

2.2.2. Binocular Vision Assessment

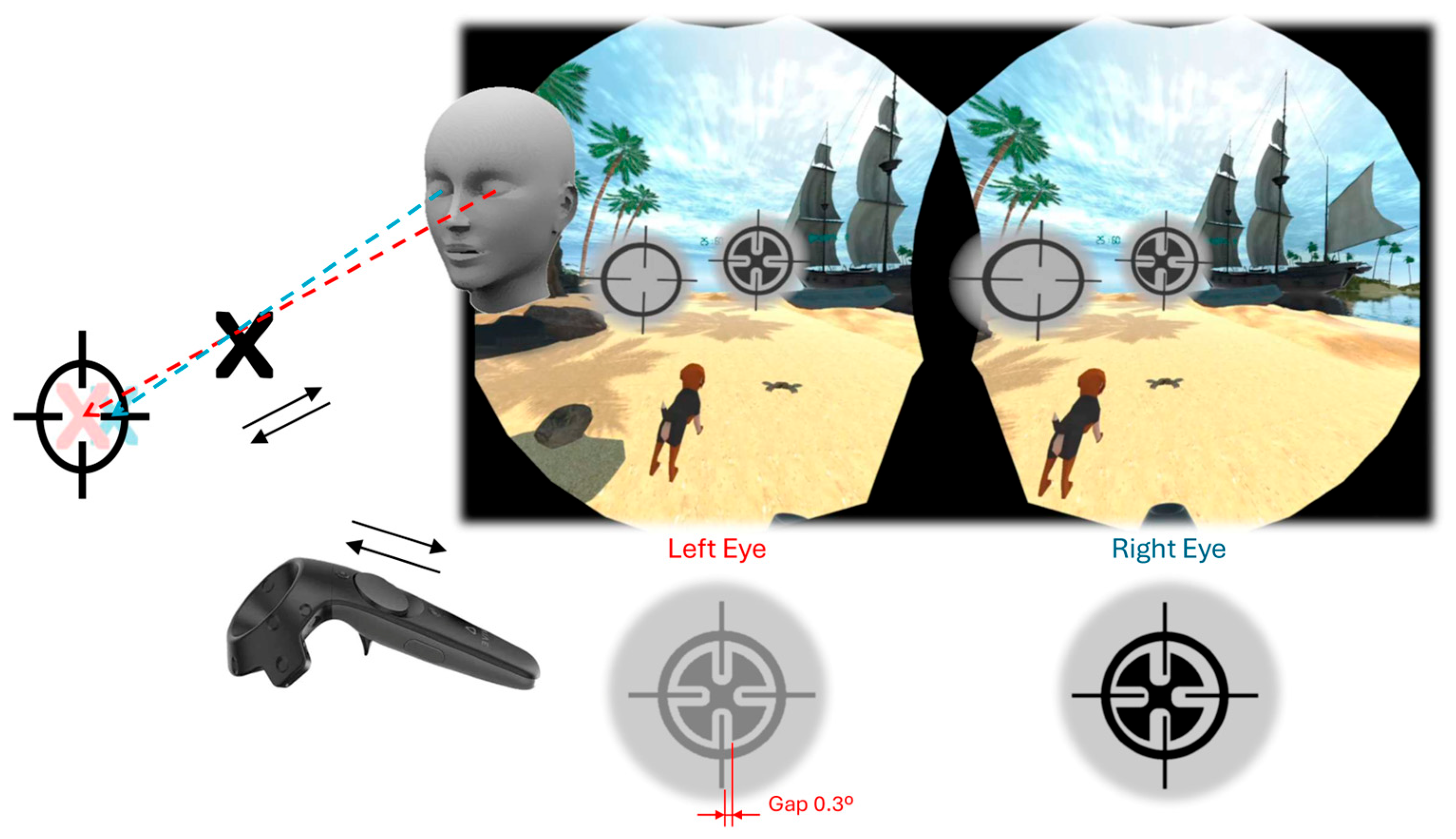

2.2.3. Intervention

2.3. Statistical Analysis

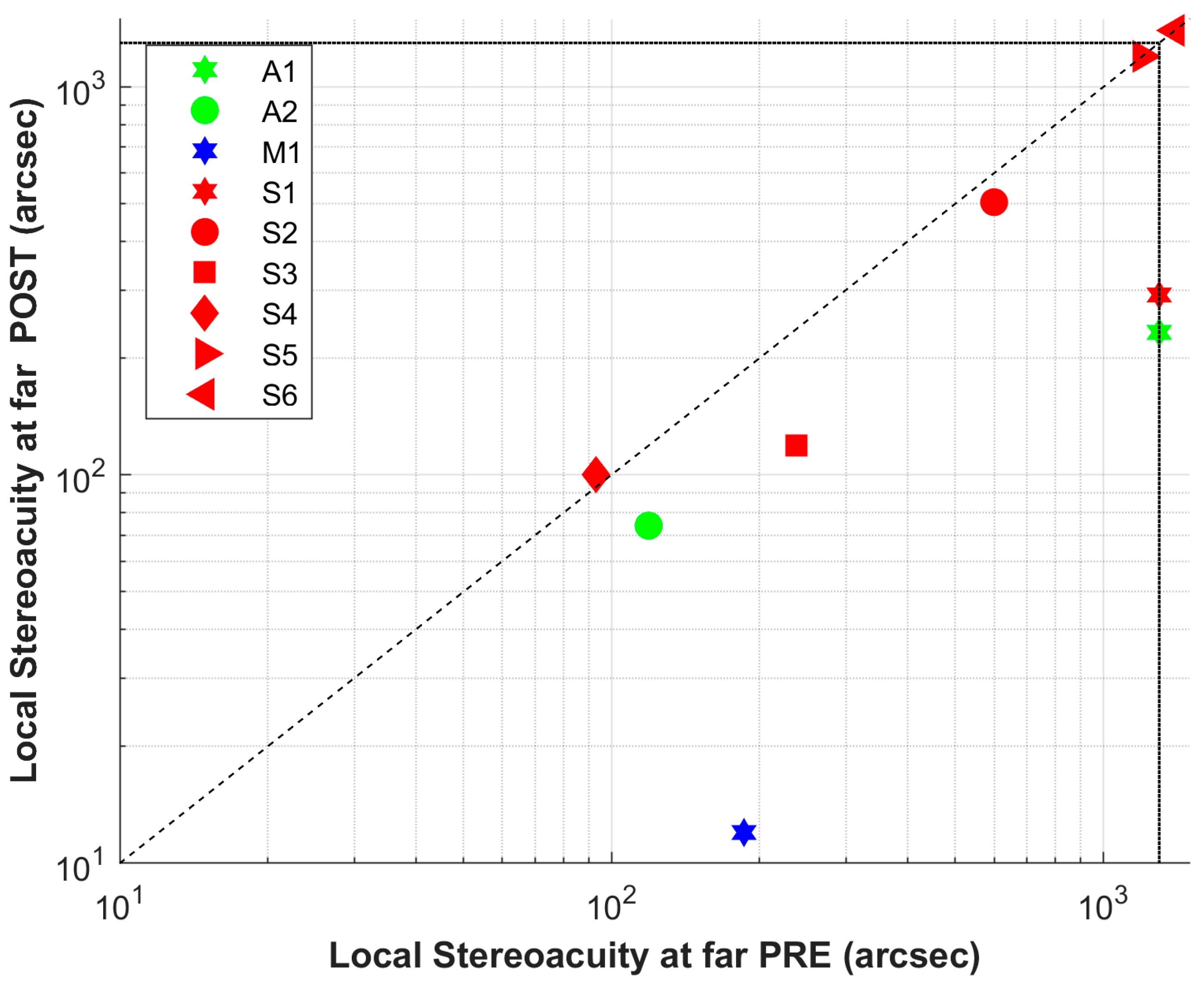

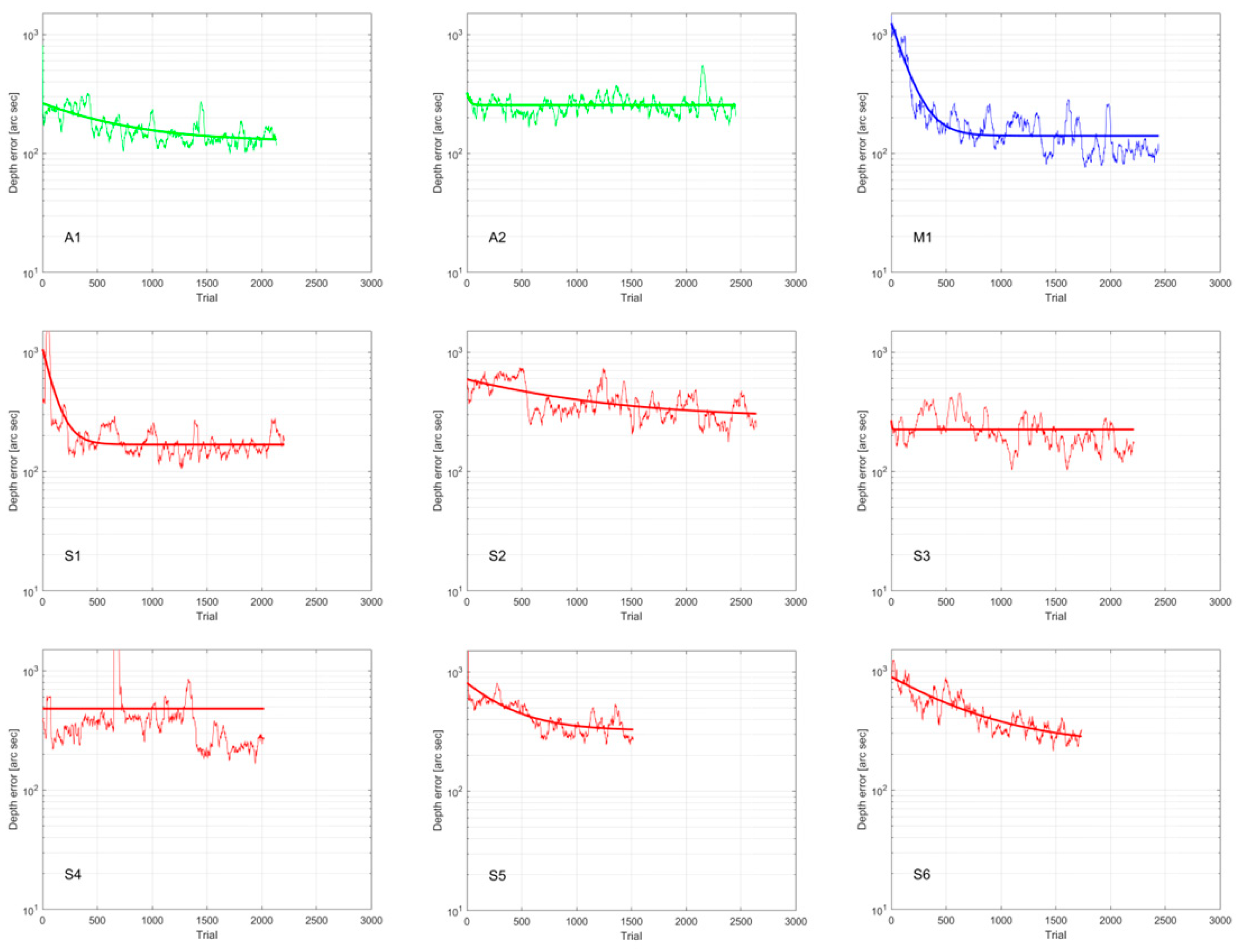

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| RTC | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| BCVA | Best-Corrected Visual Acuity |

| BF | Binocular Function |

| UCT | Unilateral Cover Test |

| FV | Fusional Vergence |

| PFV/NFV | Positive/Negative FV |

| RC | Retinal Correspondence |

| NRC | Normal RC |

| ARC | Anomalous RC |

| HARC | Harmonious ARC |

| UHARC | Unharmonious ARC |

| SA | Stereoacuity |

| LE/RE | Left/Right Eye |

Appendix A

| ID | Sex | Age | Rx | AA | MEM | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | M | 35 | −1.50/−1.75 | 5/5 | +1.0/+1.0 | Overcorrected with negative lens |

| N2 | F | 52 | −1.50/−1.75/Ad +2.00 | - | - | Presbyopic |

| N3 | M | 23 | −2.25 −0.50 95°/−1.50 −1.25 90° | 20/20 | +0.50/+0.50 | Protanomalous |

| N4 | M | 44 | +0.25/+0.50 | 6.66/5 | +0.50/+1.0 | |

| N5 | M | 22 | +1.25/+1.25 | 6.66/6.66 | +1.00/+1.00 |

| ID | UCT Distance | UCT Near | FV Distance | FV Near | Worth Test | Contrast Ratio | SA Local Distance | SA Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 2EF | ortho | PFV 30/25 NFV 6/2 | PFV 45/40 NFV 14/10 | Fusion | 1.05 | 23 | 63 |

| N2 | 2EF | 12EF | PFV 25/20 NFV 4/1 | PFV 45/35 NFV 12/10 | Fusion | 1.24 | 163 | 63 |

| N3 | ortho | 2XF | PFV 25/20 NFV 8/4 | PFV 25/20 NFV 16/12 | Fusion | 1.32 | 47 | 63 |

| N4 | ortho | ortho | PFV 25/16 NFV 10/6 | PFV > 45 NFV 20/18 | Fusion | 1.22 | 163 | 63 |

| N5 | 2XF | 6XF | PFV 16/12 NFV 10/6 | PFV 30/25 NFV 20/14 | Fusion | 1.32 | 12 | 63 |

| ID | Hours | Sessions | Days | Initial Error | Final Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 1.32 | 3 | 3 | 25 | 36 |

| N2 | 1.31 | 3 | 3 | 98 | 56 |

| N3 | 1.30 | 3 | 3 | 31 | 38 |

| N4 | 1.31 | 3 | 3 | 36 | 33 |

| N5 | 1.30 | 3 | 3 | 80 | 52 |

References

- Wade, N.J.; Swanston, M. Visual Perception: An Introduction, 3rd ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–322. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, D.M. Learning to see in depth. Vision Res. 2022, 200, 108082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopin, A.; Silver, M.A.; Sheynin, Y.; Ding, J.L.D. Transfer of Perceptual Learning From Local Stereopsis to Global Stereopsis in Adults With Amblyopia: A Preliminary Study. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 719120. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, D.M.; Knill, D.C.; Bavelier, D. Stereopsis and amblyopia: A mini-review. Vision Res. 2015, 114, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Thompson, B.; Lam, C.S.; Deng, D.; Chan, L.Y.; Maehara, G.; Woo, G.C.; Yu, M.; Hess, R.F. The role of suppression in amblyopia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 4169–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, R.J.; Clavagnier, S.R.; Bobier, W.; Thompson, B.H.R. The regional extent of suppression: Strabismics versus nonstrabismics. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 6585–6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, D.M.; McKee, S.P.; Movshon, J.A. Visual deficits in anisometropia. Vision Res. 2011, 51, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloper, J. New Treatments for Amblyopia—To Patch or Play ? JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 1408–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Portela-Camino, J.A.; Martín-González, S.; Ruiz-Alcocer, J.; Illarramendi-Mendicute, I.; Garrido-Mercado, R. A Random Dot Computer Video Game Improves Stereopsis. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2018, 95, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedamurthy, I.; Knill, D.C.; Huang, S.J.; Yung, A.; Ding, J.; Kwon, O.S.; Bavelier, D.; Levi, D.M. Recovering stereo vision by squashing virtual bugs in a virtual reality environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinez, A.; Martín-González, S.; Ibarrondo, O.; Levi, D.M. Scaffolding depth cues and perceptual learning in VR to train stereovision: A proof of concept pilot study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, E.B.; Cumming, B.G.L.M. Integration of stereopsis and motion shape cues. Vis. Res. 1994, 34, 2259–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, H.; Preston, T.J.; Meeson, A.W.A. The integration of motion and disparity cues to depth in dorsal visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, D.M. Applications and implications for extended reality to improve binocular vision and stereopsis. J. Vis. 2023, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.M.; Cotter, S.A.; Study, A.T.; Eye, P.; Investigator, D.; Concerns, Q. The Amblyopia Treatment Studies: Implications for Clinical Practice. Adv. Ophthalmol. Optom. 2016, 1, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.M.; Leske, D.A.; Hohberger, G.G. Defining real change in prism-cover test measurements. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 145, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, S.; Portela, J.A.; Ding, J.; Ibarrondo, O.; Levi, D.M. Evaluation of a Virtual Reality implementation of a binocular imbalance test. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopin, A.; Bavelier, D.; Levi, D.M. The prevalence and diagnosis of ‘stereoblindness’ in adults less than 60 years of age: A best evidence synthesis. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2019, 39, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, M.W.F. Distance discrimination. Effect on threshold of lateral separation of the test objects. Arch. Ophthal. 1948, 39, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fendick, M.; Westheimer, G. Effects of practice and the separation of test targets on foveal and peripheral stereoacuity. Vision Res. 1983, 23, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gantz, L.; Bedell, H.E. Variation of Stereothreshold with Random-Dot Stereogram Density. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2011, 88, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, A.L.; Wood, J.M.; Thompson, B.; Birch, E.E. From suppression to stereoacuity: A composite binocular function score for clinical research. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2019, 39, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gantz, L.B.H. Transfer of perceptual learning of depth discrimination between local and global stereograms. Vis. Res. 2010, 50, 1891–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Levi, D.M. Recovery of stereopsis through perceptual learning in human adults with abnormal binocular vision. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, E733–E741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela-Camino, J.A.; Martín-González, S.; Ruiz-Alcocer, J.; Illarramendi-Mendicute, I.; Piñero, D.P.; Garrido-Mercado, R. Predictive factors for the perceptual learning in stereodeficient subjects. J. Optom. 2021, 14, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astle, A.T.; McGraw, P.V.W.B. Recovery of stereo acuity in adults with amblyopia. BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 2011, bcr0720103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Jia, W.L.; Feng, L.X.; Lu, Z.L.; Huang, C.B. Perceptual learning improves stereoacuity in amblyopia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | Sex | Age | Rx | BCVA | AA | MEM | Prev. Tx | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | F | 19 | +0.50/+1.50 −0.50@180° | 1.25/0.9–2 | 10/6.66 | +0.25/+0.75 | Occlusion | Amb. Aniso |

| A2 | M | 37 | +4.50 −3.00@20°/0.00 | 0.8/1.2 | 6.75/8.25 | +3.00/+0.00 | Amb. Aniso | |

| M1 | F | 19 | +1.50 −0.50@170°/+4.75 −1.25@175° | 1.6/0.8 + 3 | 12.5/8.33 | +1.25/+2.00 | Occlusion | Amb. Aniso XT Int. |

| S1 | F | 20 | −1.00/+0.25 (Overminus −1.50) | 1.0/1.0 | 10/10 | −0.25/+0.25 | XT int. | |

| S2 | M | 27 | +3.75 +2.00@90°/+2.50 +1.75@70° | 1.0/1.0 | 15/15 | +0.75/+1.25 | XT int | |

| S3 | F | 19 | +7.00 −2.50@20°/+6.50 −3.50@165° | 1.0/1.0 | 15/15 | +0.75/+1.25 | XT alt. | |

| S4 | F | 19 | +2.50 −1.50@180°/+2.00 | 0.8/1.26 | 7.7/7.7 | +0.75/+0.75 | Sx RE ET | Amb. ET |

| S5 | F | 53 | +1.25/+0.50 | 0.8/1.26 | presbyopic | +1.00/+1.00 | Occlusion | Amb. ET |

| S6 | M | 58 | +1.00/+2.00 | 1.25/0.8 | presbyopic | +0.75/+1.25 | Occlusion | Amb. ET |

| ID | UCT Distance | UCT Near | RC | FV Distance | FV Near | Worth Test | Ratio | SA Local Distance | SA Local Near | SA Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 3EF | 3EF | NRC | NFV 12/6 PFV 18/12 | NFV 14/12 PFV 30/20 | Sup. LE | 1.02 | no | 400 | no |

| A2 | ortho | ortho | NRC | NFV 4/2 PFV 10/8 | NFV 14/12 PFV -/- | Fusion | 6.43 | 119 | 500 | no |

| M1 | 18XT int. | 20XT int. | NRC | NFV 18/16 PFV 6/- | NFV 20/18 PFV -/- | Int. Sup. | 2.03 | 186 | 100 | no |

| S1 | 18XT int. | 14XT int. | NRC | NFV 20/10 PFV -/- | NFV 25/- PFV > 45 | Int. Sup. | 1.13 | no | 200 | no |

| S2 | 8XT int. | 12XT int. | NRC | NFV 10/8 PFV 16/8 | NFV 3/0 PFV 18/14 | Int. Sup. | 1.10 | 600 | 400 | no |

| S3 | 12XT | 15XT | NRC | NFV 12/8 PFV 25/16 | NFV 30/25 PFV 14/12 | Alt. Int. Sup. | 5.19 | 238 | no | no |

| S4 | 16ET-3HPT 2 | 18ET-2HPT 2 | UHARC 2 | no | no | Diplopia | 1.95 | 93 | 50 | no |

| S5 | 14 ET | 16 ET | NRC | no | no | Sup. RE | 12.00 | no | no | no |

| S6 | 10ET | 10ET | HARC | no | no | Sup. LE | 12.00 | no | no | no |

| UCT, Unilateral Cover Test; EF, esophoria; XF, exophoria; ET, esotropia; XT, exotropia; HPF, hyperphoria; RC, retinal correspondence; NRC, normal RC; ARC, anomalous RC; HARC, Harmonious ARC; UHARC, Unharmonious ARC; FV, fusional vergences; NFV/PFV, negative/positive FV; Int., intermittent; Alt., alternant; Sup., suppression; LE/RE, left/right eye; Ratio, binocular contrast ratio; SA, stereoacuity. CT and FV in diopters; SA in seconds of arc; Ratio unitless. | ||||||||||

| 2 S4 was diagnosed with strabismus at age 3 and underwent surgery at 14. The subjective deviation was 6Δ at both distance and near. | ||||||||||

| ID | UCT Distance | UCT Near | RC | FV Distance | FV Near | Worth Test | Ratio | SA Local Distance | SA Local Near | SA Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 3EF | 3EF | NRC | NFV 25/12 PFV 30/20 | NFV 12/10 PFV > 45 | Fusion | 1.02 | 233 | 63 | no 2 |

| A2 | Orto | orto | NRC | NFV 4/2 PFV 8/4 | NFV 10/8 PFV 6/4 | Fusion | 1.68 | 74 | 250 | no |

| M1 | 16XT | 18XT inter. | NRC | NFV 16/14 PFV 6/- | NFV 25/20 PFV 10/6 | Fusion | 1.78 | 12 | 16 | 125 |

| S1 | 10XF/10XF (OM) | 10XF/6XF (OM) | NRC | NFV 16/12 PFV 10/- | NFV 20/16 PFV > 45 | Fusion | 1.13 | 291 | 16 | 125 |

| S2 | 6XT int. | 3XT int. | NRC | NFV 10/6 PFV 25/18 | NFV 8/6 PFV 25/18 | Int. Sup. | 3.30 | 505 | 100 | 500 |

| S3 | 6XT | 3XT | NRC | NFV 16/18 PFV 10/8 | NFV 30/25 PFV 16/12 | Alt. Int. Sup. | 2.38 | 119 | 160 | no |

| S4 | 16ET-3HPT | 18ET-2HPT | UHARC | no | no | Diplopia | 2.10 | 100 | 50 | 500 |

| S5 | 14 ET | 16 ET | NRC | no | no | Fusion | 7.97 | no | no | no |

| S6 | 12ET | 12ET | HARC | no | no | Sup. LE | 7.97 | no | no | no |

| UCT, Unilateral Cover Test; EF, esophoria; XF, exophoria; ET, esotropia; XT, exotropia; HPF, hyperphoria; OM, overminus; RC, retinal correspondence; NRC, normal RC; ARC, anomalous RC; HARC, Harmonious ARC; UHARC, Unharmonious ARC; FV, fusional vergences; NFV/PFV, negative/positive FV; Int., intermittent; Alt., alternant; Sup., suppression; LE/RE, left/right eye; Ratio, binocular contrast ratio; SA, stereoacuity. CT and FV in diopters; SA in seconds of arc; Ratio unitless. | ||||||||||

| 2 A1 reports perceiving a protrusion in the random-dot pattern but is unable to identify its shape | ||||||||||

| Pre | Post | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | p |

| BF | 4.33 ± 0.50 | 4.00 (1.00) | 3.51 ± 1.14 | 4.00 (1.30) | 0.03 * |

| Ratio | 4.76 ± 4.52 | 2.03 (5.30) | 3.26 ± 2.76 | 2.10 (1.62) | 0.09 |

| Depth Error | 752.11 ± 384.50 | 547.00 (553.00) | 221.78 ± 79.12 | 236.00 (105.00) | <0.01 * |

| Near | |||||

| SA global | 1300 ± 0.00 | 1300.00 (0.00) | 861.11 ± 537.08 | 1300.00 (800.00) | 0.06 |

| SA local | 616.67 ± 532.68 | 400.00 (1100.00) | 361.67 ± 537.11 | 100.00 (200.00) | 0.03 * |

| UCT | 15.00 ± 3.42 | 15.00 (4.00) | 11.43 ± 6.48 | 12.00 (10.50) | 0.10 |

| NFV Break | 12.67 ± 5.75 | 12.00 (6.00) | 14.50 ± 7.04 | 16.00 (4.50) | 0.58 |

| NFV Recovery | 8.33 ± 4.63 | 8.00 (3.00) | 10.67 ± 5.75 | 12.00 (6.00) | 0.34 |

| PFV Break | 12.50 ± 8.98 | 13.00 (10.50) | 14.85 ± 10.05 | 10.00 (12.75) | 0.69 |

| PFV Recovery | 7.33 ± 6.41 | 8.00 (9.00) | 8.33 ± 8.80 | 6.00 (14.50) | 0.58 |

| Distance | |||||

| SA local | 715.11 ± 573.54 | 600.00 (1114.00) | 437.11 ± 510.41 | 233.00 (405.00) | 0.03 * |

| UCT | 13.71 ± 3.90 | 14.00 (6.00) | 11.43 ± 4.28 | 12.00 (7.00) | 0.13 |

| NFV Break | 17.67 ± 9.52 | 17.00 (9.75) | 17.50 ± 8.89 | 16.00 (13.25) | 0.89 |

| NFV Recovery | 11.71 ± 9.89 | 12.00 (13.50) | 14.17 ± 7.44 | 13.00 (10.50) | 0.42 |

| PFV Break | 17.83 ± 17.53 | 16.00 (23.50) | 24.50 ± 17.12 | 20.50 (28.50) | 0.04 * |

| PFV Recovery | 15.17 ± 16.64 | 13.00 (15.50) | 21.67 ± 18.67 | 15.00 (30.75) | 0.06 |

| ID | Hours | Sessions | Days | Total Trials | Initial Error 1 | Final Error 1 |

| A1 | 3.06 | 7 | 12 | 2173 | 386 | 138 |

| A2 | 4.01 | 8 | 14 | 2492 | 397 | 236 |

| M1 | 3.51 | 8 | 10 | 2478 | 954 | 106 |

| S1 | 3.72 | 9 | 29 | 2244 | 1300 | 181 |

| S2 | 4.20 | 6 | 21 | 2680 | 547 | 319 |

| S3 | 4.10 | 7 | 31 | 2252 | 464 | 170 |

| S4 | 2.98 | 8 | 22 | 2061 | 434 | 237 |

| S5 | 4.56 | 11 | 23 | 1556 | 1300 | 334 |

| S6 | 6.15 | 11 | 24 | 1776 | 987 | 275 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Calderón-González, M.T.; Sánchez-Pavón, I.; Portela-Camino, J.A.; Martín-González, S. Effects of Perceptual Learning Through Binocular Virtual Reality Exercises on Low Stereopsis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010006

Calderón-González MT, Sánchez-Pavón I, Portela-Camino JA, Martín-González S. Effects of Perceptual Learning Through Binocular Virtual Reality Exercises on Low Stereopsis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalderón-González, María Teresa, Irene Sánchez-Pavón, Juan A. Portela-Camino, and Santiago Martín-González. 2026. "Effects of Perceptual Learning Through Binocular Virtual Reality Exercises on Low Stereopsis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010006

APA StyleCalderón-González, M. T., Sánchez-Pavón, I., Portela-Camino, J. A., & Martín-González, S. (2026). Effects of Perceptual Learning Through Binocular Virtual Reality Exercises on Low Stereopsis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010006