Synovial Periprosthetic Infection Markers Show High Variability in Different Clinical and Microbiological Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

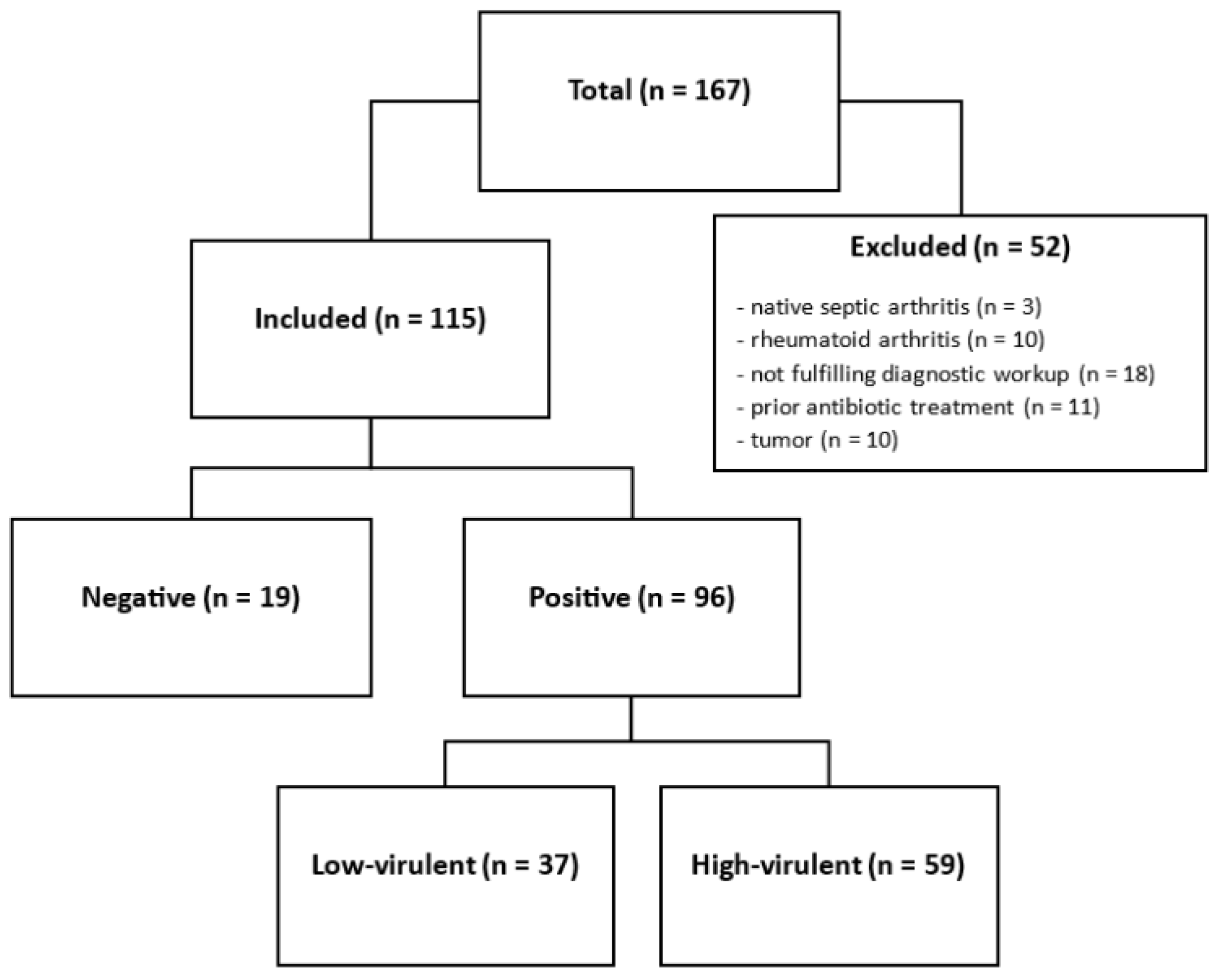

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Pathogen Detection

3.2. Clinical Appearance, Histology, Virulence

3.3. Associations Between WBC and Clinical and Diagnostic Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pannu, T.S.; Villa, J.M.; Higuera, C.A. Diagnosis and management of infected arthroplasty. SICOT J. 2021, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inacio, M.C.S.; Paxton, E.W.; Graves, S.E.; Namba, R.S.; Nemes, S. Projected increase in total knee arthroplasty in the United States—An alternative projection model. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 1797–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Ong, K.; Lau, E.; Mowat, F.; Halpern, M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2007, 89, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.M.; Ong, K.L.; Lau, E.; Bozic, K.J.; Berry, D.; Parvizi, J. Prosthetic joint infection risk after TKA in the Medicare population. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010, 468, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundtoft, P.H.; Pedersen, A.B.; Varnum, C.; Overgaard, S. Increased Mortality After Prosthetic Joint Infection in Primary THA. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2017, 475, 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, N.T.; Della Valle, C.J. Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infection-An Algorithm-Based Approach. J. Arthroplast. 2017, 32, 2047–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozic, K.J.; Ries, M.D. The impact of infection after total hip arthroplasty on hospital and surgeon resource utilization. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2005, 87, 1746–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Akgün, D.; Trampuz, A.; Perka, C.; Renz, N. High failure rates in treatment of streptococcal periprosthetic joint infection: Results from a seven-year retrospective cohort study. Bone Jt. J. 2017, 99, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, P.S.; Vicente, M.; Carrera, L.; Rodríguez-Pardo, D.; Corró, S. Current actual success rate of the two-stage exchange arthroplasty strategy in chronic hip and knee periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Jt. J. 2020, 102, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenguerrand, E.; Whitehouse, M.R.; Beswick, A.D.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Webb, J.C.; Mehendale, S.; Porter, M.; Blom, A.W. Mortality and re-revision following single-stage and two-stage revision surgery for the management of infected primary hip arthroplasty in England and Wales. Bone Jt. Res. 2023, 12, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheir, M.M.; Tan, T.L.; Shohat, N.; Foltz, C.; Parvizi, J. Routine Diagnostic Tests for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Demonstrate a High False-Negative Rate and Are Influenced by the Infecting Organism. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2018, 100, 2057–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvec, S.; Portillo, M.E.; Pasticci, B.M.; Borens, O.; Trampuz, A. Epidemiology and new developments in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2012, 35, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, S.; Ricciardi, B.F.; Briggs, T.W.; Sussmann, P.S.; Bostrom, M.P. Evaluation and Management of Periprosthetic Joint Infection-an International, Multicenter Study. HSS J. 2014, 10, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, K.K.; Wood, S.; Tarity, T.D. Low-Virulence Organisms and Periprosthetic Joint Infection-Biofilm Considerations of These Organisms. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2018, 11, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trampuz, A.; Piper, K.E.; Jacobson, M.J.; Hanssen, A.D.; Unni, K.K.; Osmon, D.R.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Cockerill, F.R.; Steckelberg, J.M.; Greenleaf, J.F.; et al. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, S.; Lepetsos, P.; Stylianakis, A.; Vlamis, J.; Birbas, K.; Kaklamanos, I. Superiority of the sonication method against conventional periprosthetic tissue cultures for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infections. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2018, 28, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, M.; Sousa, R.; Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M.; Chen, A.F.; Soriano, A.; Vogely, H.C.; Clauss, M.; Higuera, C.A.; Trebše, R. The EBJIS definition of periprosthetic joint infection: A practical guide for clinicians. Bone Jt. J. 2021, 103, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unter Ecker, N.; Suero, E.M.; Gehrke, T.; Haasper, C.; Zahar, A.; Lausmann, C.; Hawi, N.; Citak, M. Serum C-reactive protein relationship in high- versus low-virulence pathogens in the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.L.; Kheir, M.M.; Shohat, N.; Tan, D.D.; Kheir, M.; Chen, C.; Parvizi, J. Culture-Negative Periprosthetic Joint Infection: An Update on What to Expect. JBJS Open Access 2018, 3, e0060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArthur, B.A.; Abdel, M.P.; Taunton, M.J.; Osmon, D.R.; Hanssen, A.D. Seronegative infections in hip and knee arthroplasty: Periprosthetic infections with normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level. Bone Jt. J. 2015, 97, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvizi, J.; Tan, T.L.; Goswami, K.; Higuera, C.; Della Valle, C.; Chen, A.F.; Shohat, N. The 2018 Definition of Periprosthetic Hip and Knee Infection: An Evidence-Based and Validated Criteria. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 1309–1314.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izakovicova, P.; Borens, O.; Trampuz, A. Periprosthetic joint infection: Current concepts and outlook. EFORT Open Rev. 2019, 4, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deirmengian, C.A.; Citrano, P.A.; Gulati, S.; Kazarian, E.R.; Stave, J.W.; Kardos, K.W. The C-Reactive Protein May Not Detect Infections Caused by Less-Virulent Organisms. J. Arthroplast. 2016, 31, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costerton, J.W. Biofilm theory can guide the treatment of device-related orthopaedic infections. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005, 437, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzeng, A.; Tzeng, T.H.; Vasdev, S.; Korth, K.; Healey, T.; Parvizi, J.; Saleh, K.J. Treating periprosthetic joint infections as biofilms: Key diagnosis and management strategies. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 81, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbari, E.F.; Marculescu, C.; Sia, I.; Lahr, B.D.; Hanssen, A.D.; Steckelberg, J.M.; Gullerud, R.; Osmon, D.R. Culture-negative prosthetic joint infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, C.; Cabric, S.; Perka, C.; Trampuz, A.; Renz, N. Synovial fluid multiplex PCR is superior to culture for detection of low-virulent pathogens causing periprosthetic joint infection. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 90, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazanave, C.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K.E.; Hanssen, A.D.; Karau, M.J.; Schmidt, S.M.; Gomez Urena, E.O.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Osmon, D.R.; Lough, L.E.; Pritt, B.S.; et al. Rapid molecular microbiologic diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 2280–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achermann, Y.; Vogt, M.; Leunig, M.; Wüst, J.; Trampuz, A. Improved diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection by multiplex PCR of sonication fluid from removed implants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, K.; Parvizi, J.; Maxwell Courtney, P. Current Recommendations for the Diagnosis of Acute and Chronic PJI for Hip and Knee-Cell Counts, Alpha-Defensin, Leukocyte Esterase, Next-generation Sequencing. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2018, 11, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardete-Hartmann, S.; Mitterer, J.A.; Sebastian, S.; Frank, B.J.; Simon, S.; Huber, S.; Löw, M.; Sommer, I.; Prinz, M.; Halabi, M.; et al. The role of BioFire Joint Infection Panel in diagnosing periprosthetic hip and knee joint infections in patients with unclear conventional microbiological results. Bone Jt. Res. 2024, 13, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kildow, B.J.; Ryan, S.P.; Danilkowicz, R.; Lazarides, A.L.; Penrose, C.; Bolognesi, M.P.; Jiranek, W.; Seyler, T.M. Next-generation sequencing not superior to culture in periprosthetic joint infection diagnosis. Bone Jt. J. 2021, 103, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarabichi, M.; Shohat, N.; Goswami, K.; Alvand, A.; Silibovsky, R.; Belden, K.; Parvizi, J. Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infection: The Potential of Next-Generation Sequencing. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2018, 100, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | |

| Age * | 71.1 (sd = 12.4) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 55 |

| Female | 60 |

| Joint | |

| Hip | 40 |

| Knee | 75 |

| Variable * | p-Value † | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Pathogen Detection | negative | positive | |

| WBC G/L | 16.35 [32.0] | 42.44 [87.0] | <0.01 |

| PMN% | 86.0 [60.0] | 91.0 [10.0] | <0.01 |

| Histology | negative | positive | |

| WBC G/L | 16.73 [44.0] | 42.86 [87.0] | <0.01 |

| PMN% | 86.0 [67.0] | 91.0 [9.0] | =0.036 |

| Symptom Duration | >4 weeks | ≤4 weeks | |

| WBC G/L | 16.42 [46.0] | 58.27 [112.0] | <0.01 |

| PMN% | 88.0 [20.0] | 91.50 [9.0] | =0.042 |

| Virulence | low | high | |

| WBC G/L | 27.27 [46.0] | 58.27 [102.0] | <0.01 |

| PMN% | 91.0 [13.0] | 91.0 [10.0] | =0.631 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ortmayr, J.; Straub, J.; Vertesich, K.; Sigmund, I.K.; Böhler, C.; Windhager, R.; Staats, K. Synovial Periprosthetic Infection Markers Show High Variability in Different Clinical and Microbiological Settings. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010052

Ortmayr J, Straub J, Vertesich K, Sigmund IK, Böhler C, Windhager R, Staats K. Synovial Periprosthetic Infection Markers Show High Variability in Different Clinical and Microbiological Settings. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtmayr, Joachim, Jennifer Straub, Klemens Vertesich, Irene Katharina Sigmund, Christoph Böhler, Reinhard Windhager, and Kevin Staats. 2026. "Synovial Periprosthetic Infection Markers Show High Variability in Different Clinical and Microbiological Settings" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010052

APA StyleOrtmayr, J., Straub, J., Vertesich, K., Sigmund, I. K., Böhler, C., Windhager, R., & Staats, K. (2026). Synovial Periprosthetic Infection Markers Show High Variability in Different Clinical and Microbiological Settings. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010052