COPD and Cardiovascular Diseases: Biomarker-Guided Stratification and Therapeutic Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

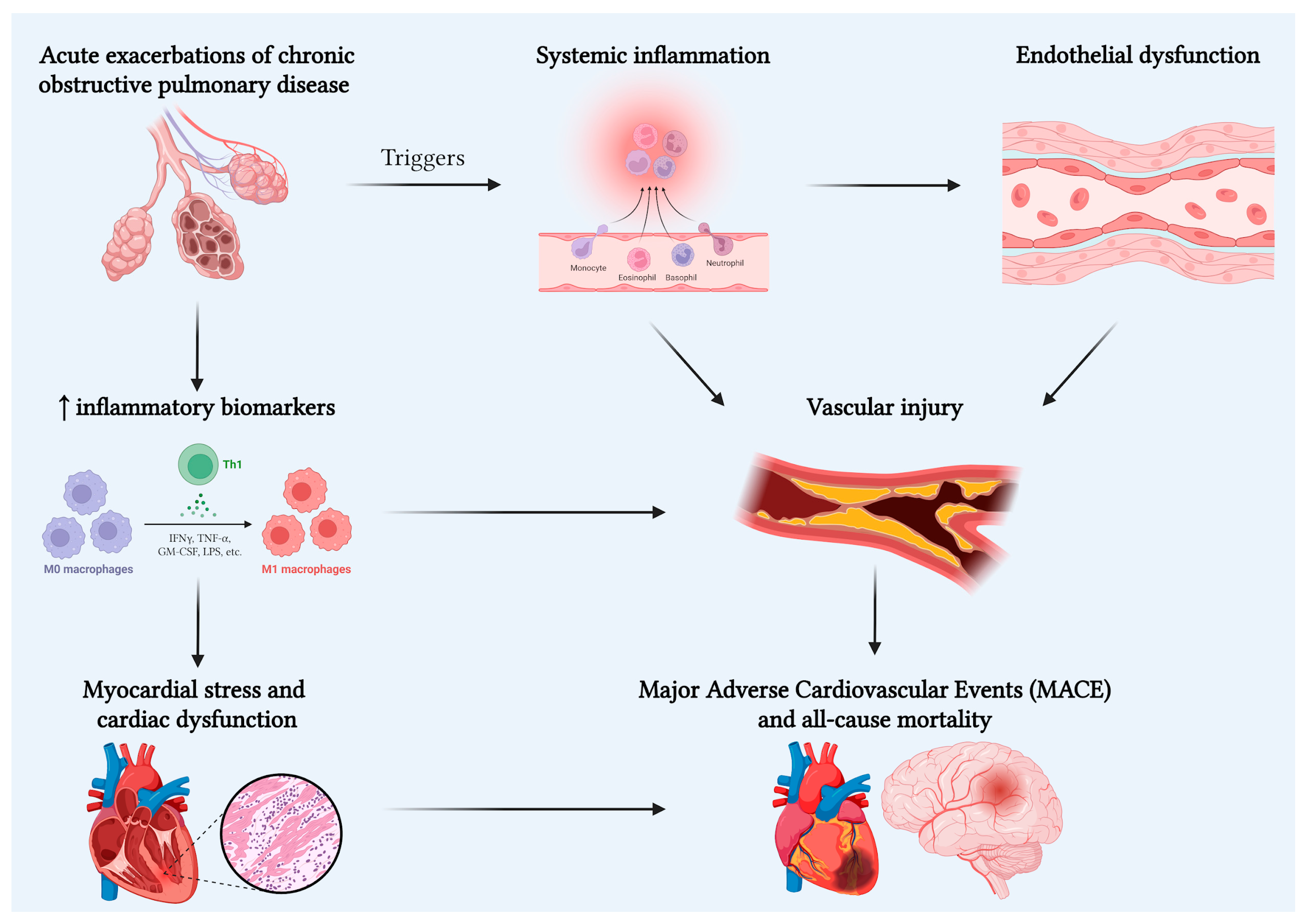

3. Linking Mechanisms

4. Biomarkers

5. Prognostic Value for MACE and All-Cause Mortality

6. Clinical and Research Implications

Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Egervall, K.; Rosso, A.; Elmståhl, S. Association between cardiovascular disease- and inflammation-related serum biomarkers and poor lung function in elderly. Clin. Proteom. 2021, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Papaporfyriou, A.; Bartziokas, K.; Gompelmann, D.; Idzko, M.; Fouka, E.; Zaneli, S.; Papaioannou, A.I. Cardiovascular Diseases in COPD: From Diagnosis and Prevalence to Therapy. Life 2023, 13, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curkendall, S.M.; DeLuise, C.; Jones, J.K.; Lanes, S.; Stang, M.R.; Goehring, E., Jr.; She, D. Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Saskatchewan Canada cardiovascular disease in COPD patients. Ann. Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andre’, S.; Conde, B.; Fragoso, E.; Boléo-Tome’, J.P.; Areias, V.; Cardoso, J. GI DPOC-Grupo de Interesse na Doenca Pulmonar Obstrutiva Cro’nica. COPD and Cardiovascular Disease. Pulmonology 2019, 25, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragnoli, B.; Chiazza, F.; Tarsi, G.; Malerba, M. Biological pathways and mechanisms linking COPD and cardiovascular disease. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2025, 16, 20406223251314286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Almagro, P.; Cabrera, F.J.; Diez, J.; Boixeda, R.; Alonso Ortiz, M.B.; Murio, C.; Soriano, J.B. Working Group on, COPD, Spanish Society of Internal Medicine. Comorbidities and short-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD:the EPOC en Servicios de medicina interna (ESMI) study. Chest J. 2012, 142, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, K.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Xu, Z.; Xie, B.; Dai, H. Prevalence and Impact of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Ischemic Heart Disease: A systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 18 Million Patients. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon Dis. 2024, 19, 2333–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Onishi, K. Total management of Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Li, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Sex differences in comorbidities and mortality risk among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A study based on NHANES data. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Camiciottoli, G.; Bigazzi, F.; Magni, C.; Bonti, V.; Diciotti, S.; Bartolucci, M.; Mascalchi, M.; Pistolesi, M. Prevalence of comorbidities according to predominant phenotype and severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2016, 11, 2229–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mariniella, D.F.; D’Agnano, V.; Cennamo, D.; Conte, S.; Quarcio, G.; Notizia, L.; Pagliaro, R.; Schiattarella, A.; Salvi, R.; Bainco, A.; et al. Comorbidities in COPD: Current and Future Treatment Challenges. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maclay, J.D.; McAllister, D.A.; Macnee, W. Cardiovascular risk in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology 2007, 12, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Ma, J.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. Unlocking the link: Predicting cardiovascular disease risk with a focus on airflow obstruction using machine learning. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 2025, 25, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, K.F.; Hurst, J.R.; Suissa, S. Cardiovascular disease and COPD: Dangerous liaisons? Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 180057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Taneja, V.; Vassallo, R. Cigarette smoking and inflammation: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ljubičić, Đ.; Balta, V.; Dilber, D.; Vražić, H.; Đikić, D.; Odeh, D.; Habek, J.Č.; Vukovac, E.L.; Tudoric’, N. Association of chronic inflammation with cardiovascular risk in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—A cross-sectional study. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ye, C.; Yuan, L.; Wu, K.; Shen, B.; Zhu, C. Association between systemic immune-inflammation index and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A population-based study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Meng, Y.; Adcock, I.M.; Yao, X. Role of inflammatory cells in airway remodeling in COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2018, 13, 3341–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aaron, C.P.; Schwartz, J.E.; Bielinski, S.J.; Hoffman, E.A.; Austin, J.H.; Oelsner, E.C.; Donohue, K.M.; Kalhan, R.; Berardi, C.; Kaufman, J.D.; et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and progression of percent emphysema: The MESA Lung study. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Green, C.E.; Turner, A.M. The role of the endothelium in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Linden, F.; Domschke, G.; Erbel, C.; Akhavanpoor, M.; Katus, H.A.; Gleissner, C.A. Inflammatory therapeutic targets in coronary atherosclerosis-from molecular biology to clinical application. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marcuccio, G.; Candia, C.; Maniscalco, M.; Ambrosino, P. Endothelial dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An update on mechanisms, assessment tools and treatment strategies. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1550716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sin, D.D.; Man, S.F. Why are patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases? The potential role of systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Circulation 2003, 107, 1514–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodorakopoulou, M.P.; Alexandrou, M.E.; Bakaloudi, D.R.; Pitsiou, G.; Stanopoulos, I.; Kontakiotis, T.; Boutou, A.K. Endothelial dysfunction in COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using different functional assessment methods. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00983–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapp, B.R.; Hingorani, A.D.; Kharbanda, R.K.; Mohamed-Ali, V.; Stephens, J.W.; Vallance, P.; MacAllister, R.J. Inflammation-induced endothelial dysfunction involves reduced nitric oxide bioavailability and increased oxidant stress. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 64, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polverino, F.; Celli, B.R.; Owen, C.A. COPD as an endothelial disorder: Endothelial injury linking lesions in the lungs and other organs? (2017 Grover Conference Series). Pulm. Circ. 2018, 8, 2045894018758528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Taraseviciene-Stewart, L.; Voelkel, N.F. Molecular pathogenesis of emphysema. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanfleteren, L.E.; Spruit, M.A.; Groenen, M.T.; Bruijnzeel, P.L.; Taib, Z.; Rutten, E.P.; Op ‘t Roodt, J.; Akkermans, M.A.; Wouters, E.F.; Franssen, F.M. Arterial stiffness in patients with COPD: The role of systemic inflammation and the effects of pulmonary Rehabilitation. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 43, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, A.D.; Zakeri, R.; Quint, J.K. Defening the relationship between COPD and CVD: What are the implications for clinical practice? Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2018, 12, 1753465817750524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maclay, J.D.; McAllister, D.A.; Johnston, S.; Raftis, J.; McGuinnes, C.; Deans, A.; Newby, D.E.; Mills, N.L.; MacNee, W. Increased platelet activation in patients with stable and Acute exacerbation of COPD. Thorax 2011, 66, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Morrell, N.W.; Archer, S.L.; Stenmark, K.R.; MacLean, M.R.; Lang, I.M.; Christman, B.W.; Weir, E.K.; Eickelberg, O.; Voelkel, N.F.; et al. Cellular and Molecular pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 43, 13S–24S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malerba, M.; Olivini, A.; Radaeli, A.; Ricciardolo, F.L.; Clini, E. Platelet activation and cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2016, 32, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Hong, Q.; Xu, R. Platelet indices and the risk of pulmonary arterial hypertension:a two-sample and multivariable Mendelian randomization study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1395245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coppolino, I.; Ruggeri, P.; Nucera, F.; Cannavo, M.F.; Adcock, I.; Girbino, G.; Caramori, G. Role of stem cells in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary emphysema. COPD 2018, 15, 536–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamitava, L.; Cazzoletti, L.; Ferrari, M.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Jalil, A.; Degan, P.; Fois, A.G.; Zinellu, E.; Fois, S.S.; Fratta Pasini, A.M.; et al. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Chronic Airway Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- King, P.T. Inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its role in cardiovascular disease and lung cancer. Clin. Transl. Med. 2015, 4, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barnes, P.J. Oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 50965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, B.D.; Mitchell, P.D.; McNicholas, W.T. Hypoxemia in patients with COPD: Cause, effects, and disease progression. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2011, 6, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Polman, R.; Hurst, J.R.; Uysal, O.F.; Mandal, S.; Linz, D.; Simons, S. Cardiovascular disease and risk in COPD: A state of the art review. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2024, 22, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Tian, M.; Yang, G.; Tan, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wan, P.; Wu, J. Hypoxia signaling in human health and diseases: Implications and prospects for Therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, S.; Malcolm, K.C.; Miller, S.M.; Hendry-Hofer, T.; Schaack, J.B.; White, C.W. Differential regulation of pulmonary vascular cell growth by hypoxia- Inducible transcription factor-1α and hypoxia- inducible transcription Factor-2α. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhou, F.; Zhou, J.B.; Wei, T.P.; Wu, D.; Wang, R.X. The Role of HIF-1α in Atrial Fibrillation: Recent Advances and Therapeutic Potentials. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 26, 26787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koopman, M.; Posthuma, R.; Vanfleteren, L.E.G.W.; Simons, S.O.; Franssen, F.M.E. Lung Hyperinflation as Treatable Trait in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon Dis. 2024, 19, 1562–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tzani, P.; Aiello, M.; Elia, D.; Boracchia, L.; Marangio, E.; Olivieri, D.; Clini, E.; Chetta, A. Dynamic hyperinflation is associated with a poor cardiovascular response to Exercise in COPD patients. Respir. Res. 2011, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ceasovschih, A.; Șorodoc, V.; Covantsev, S.; Balta, A.; Uzokov, J.; Kaiser, S.E.; Almaghraby, A.; Lionte, C.; Stătescu, C.; Sascău, R.A.; et al. Electrocardiogram Features in Non-Cardiac Diseases: From Mechanisms to Practical Aspects. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 1695–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lukacsovits, J.; Szollosi, G.; Varga, J.T. Cardiovascular effects of exercise induced dynamic hyperinflation in COPD patients-Dynamically hyperinflated and nonhyperinflated subgroups. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0274585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singh, B.; Goyal, A.; Patel, B.C. C-Reactive Protein: Clinical Relevance and Interpretation. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghoorah, K.; De Soyza, A.; Kunadian, V. Increased cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the potential mechanisms linking the two conditions: A review. Cardiol. Rev. 2013, 21, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, M.; Ingebrigtsen, T.S.; Marott, J.L.; Dahl, M.; Lange, P.; Vestbo, J.; Nordstgaard, B.G. Inflammatory biomarkers and exacerbations in chronic obstructive Pulmonary disease. JAMA 2013, 309, 2353–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, H.J.; Duijkers, R.; van der Valk, P.; Schoorl, M.; Daniels, J.M.A.; van der Werf, T.S.; Boersma, W.G. CRP-guided antibiotic treatment in acute excerbations of COPD in hospital admissions. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1802014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahousse, L.; Loth, D.W.; Joos, G.F.; Hofman, A.; Leufkens, H.G.; Brusselle, G.G.; Stricker, B.H. Statins, systemic inflammation and risk of death in COPD: The Rotterdam study. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 26, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvoix, A.; Dickens, J.; Haq, I.; Mannino, D.; Miller, B.; Tal-Singer, R.; Lomas, D.A. Blood fibrinogen as a biomarker of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2013, 68, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singh, D.; Criner, G.J.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Han, M.K.; Lange, P.; Lettis, S.; Lipson, D.A.; Mannino, D.; Martin, N.; et al. InforMing the Pathway of COPD Treatment (IMPACT) trial: Fibrinogen levels predict risk of moderate or severe Exacerbations. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, B.R.; Anderson, J.A.; Brook, R.; Calverley, P.; Cowans, N.J.; Crim, C.; Dixon, I.; Kim, V.; Martinez, F.J.; Morris, A.; et al. Serum biomarkers and outcomes in patients with moderate COPD: A substudy of the randomized SUMMIT trial. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2019, 6, e000431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- MacCallum, P.K. Markers of hemostasis and systemic inflammation in heart disease and atherosclerosis in smokers. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2005, 2, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wedzicha, J.A.; Seemungal, T.A.; MacCallum, P.K.; Paul, E.A.; Donaldson, G.C.; Bhowmik, A.; Jeffries, D.J.; Meade, T.W. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are accompanied by elevations of plasma fibrinogen and serum IL-6 levels. Thromb. Haemost. 2000, 84, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzola, M.; Rogliani, P.; Matera, M.G. Cardiovascular disease in patients with COPD. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Miguel Diez, J.; Chancafe Morgan, J.; Jimenez Garcia, R. The association between COPD and heart failure risk. a review. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon Dis. 2013, 8, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Adrish, M.; Nannaka, V.B.; Cano, E.J.; Bajantri, B.; Diaz-Fuentes, G. Significance of NT-pro-BNP in acute exacerbation of COPD patients without underlying left Ventricular dysfunction. Int. Chronic. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2017, 12, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Labaki, W.W.; Xia, M.; Murray, S.; Curtis, J.L.; Barr, R.G.; Bhatt, S.P.; Bleecker, E.R.; Hansel, N.N.; Cooper, C.B.; Dransfield, M.T.; et al. NT-pro BNP in stable COPD and future Exacerbation risk: Analysis of the SPIROMICS cohort. Respir. Med. 2018, 140, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hattori, K.; Ishii, T.; Motegi, T.; Kusunoki, Y.; Gemma, A.; Kida, K. Relationship between serum cardiac troponin T level and cardiopulmonary function in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2015, 10, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Waschki, B.; Alter, P.; Zeller, T.; Magnussen, C.; Neumann, J.T.; Twerenbold, R.; Sinning, C.; Herr, C.; Kahnert, K.; Fähndrich, S.; et al. High-sensitivity troponin I and all-cause mortality in patients with stable COPD: An analysis of the COSYCONET study. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1901314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neukamm, A.M.; Høiseth, A.D.; Hagve, T.A.; Søyseth, V.; Omland, T. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T levels are increased in stable COPD. Heart 2013, 99, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brekke, P.H.; Omland, T.; Holmedal, S.H.; Smith, P.; Søyseth, V.; Troponin, T. elevation and long-term mortality after chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiszniak, S.; Schwarz, Q. Exploring the Intracrine Functions of VEGF-A. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, A.; Qi, X.; Cui, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, M. Serum VEGF: Diagnostic Value of Acute Coronary Syndrome from Stable Angina Pectoris and Prognostic Value of Coronary Artery Disease. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2020, 6786302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Valipour, A.; Schreder, M.; Wolzt, M.; Saliba, S.; Kapiotis, S.; Eickhoff, P.; Burghuber, O.C. Circulating vascular endothelial growth factor and systemic inflammatory Markers in patients with stable and exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin. Sci. 2008, 115, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastva, A.M.; Wright, J.R.; Williams, K.L. Immunomodulatory roles of surfactant proteins A and D: Implications in lung disease. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2007, 4, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lock-Johansson, S.; Vestbo, J.; Sorensen, G.L. Surfactant protein D, Club cell protein 16, Pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine, C-reactive protein, and Fibrinogen biomarker variation in chronic obstructive lung disease. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dickens, J.A.; Miller, B.E.; Edwards, L.D.; Silverman, E.K.; Lomas, D.A.; Tal-Singer, R. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Study investigators. COPD association and repeatability of blood biomarkers in The ECLIPSE cohort. Respir. Res. 2011, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Colmorten, K.B.; Nexoe, A.B.; Sorensen, G.L. The Dual Role of Surfactant Protein-D in Vascular Inflammation and Development of Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hara, A.; Niwa, M.; Noguchi, K.; Kanayama, T.; Niwa, A.; Matsuo, M.; Hatano, Y.; Tomita, H. Galectin-3 as a next-generation biomarker for detecting early stage of various disease. Biomarkers 2020, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besler, C.; Lang, D.; Urban, D.; Rommel, K.P.; von Roeder, M.; Fengler, K.; Blazek, S.; Kandolf, R.; Klingel, K.; Thiele, H.; et al. Plasma and Cardiac Galectin-3 in Patients with Heart Failure Reflects Both Inflammation and Fibrosis:Implications for Its Use as a Biomarker. Circ. Heart Fail. 2017, 10, e003804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Wu, X.; Li, S.; Zhai, C.; Wang, J.; Shi, W.; Li, M. Association of Serum Galectin-3with the Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 4612–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hiramatsu, K.; Motegi, T.; Morii, K.; Kida, K. Assessment of novel cardiovascular biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wan, Y.; Fu, J. GDF15 as a key disease target and biomarker:linking chronic lung diseases and ageing. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 479, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng, M.; Bian, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Hou, G. Growth Differentiation Factor-15 as a Biomarker for Sarcopenia in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 897097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T.; Doi, K.; Matsunaga, K.; Takahashi, S.; Donishi, T.; Suga, K.; Oishi, K.; Yasuda, K.; Mimura, Y.; Harada, M.; et al. A novel role of growth Differentiation factor (GDF)-15 in overlap with sedentary lifestyle and Cognitive risk in COPD. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husebø, G.R.; Grønseth, R.; Lerner, L.; Gyuris, J.; Hardie, J.A.; Bakke, P.S.; Eagan, T.M. Growth differentiation factor-15 is a predictor of important disease outcomes in a patients with COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, C.H.; Freeman, C.M.; Nelson, J.D.; Murray, S.; Wang, X.; Budoff, M.J.; Dransfield, M.T.; Hokanson, J.E.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Kinney, G.L.; et al. COPD Gene Investigators. GDF-15 plasma levels in chronic Obstructive pulmonary disease are associated with subclinical coronary artery Disease. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geenen, L.W.; Baggen, V.J.M.; Kauling, R.M.; Koudstaal, T.; Boomars, K.A.; Boersma, E.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W.; Bosch, A.E.v.D. Growth differentiation factor-15 as candidate predictor for mortality in adults with pulmonary hypertension. Heart 2020, 106, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Liang, G.; Cheng, M. Predictive Value of GDF-15 and sST2 for Pulmonary Hypertension in Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2023, 18, 2431–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rasmussen, L.J.H.; Petersen, J.E.V.; Eugen-Olsen, J. Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor (suPAR) as a Biomarker of Systemic Chronic Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 780641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koch, A.; Voigt, S.; Kruschinski, C.; Sanson, E.; Duckers, H.; Horn, A.; Yagmur, E.; Zimmermann, H.; Trautwein, C.; Tacke, F. Circulating soluble urokinase Plasminogen activator receptor is stably elevated during the first week of Treatment in the intensive care unit and predicts mortality in critically ill Patients. Crit. Care 2011, 15, R63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, Q.; Xiong, H.; Shuai, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, L.; Lu, J.; Liu, J. The clinical value of suPAR in diagnosis and prediction for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2020, 14, 1753466620938546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rekha, D.; Johnson, P.; Das, S.; GR, S. Serum Soluble Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator Receptor: A Promising Biomarker for Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. Cureus 2025, 17, e79594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacileo, M.; Cirillo, P.; De Rosa, S.; Ucci, G.; Petrillo, G.; Musto D’aMore, S.; Sasso, L.; Maietta, P.; Spagnuolo, R.; Chiariello, M. The role of neopterin in Cardiovascular disease. Monaldi Arch. Chest. Dis. 2007, 68, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, F.; Zeng, Z.; Lei, C.; Chen, D.; Zhang, X. Neopterin in patients with COPD, asthma, and ACO: Association with endothelial and lung functions. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Tong, X.Z.; Xia, W.H.; Xie, W.L.; Yu, B.B.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L.; Tao, J. Increased plasma neopterin levels are associated with reduced endothelial Function and arterial elasticity in hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2016, 30, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.R.; Li, C.Y.; Zhang, J.; Lv, X.J. Role of sirtuin family members in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ministrini, S.; Puspitasari, Y.M.; Beer, G.; Liberale, L.; Montecucco, F.; Camici, G.G. Sirtuin 1 in Endothelial Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Aging. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 733696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yanagisawa, S.; Papaioannou, A.I.; Papaporfyriou, A.; Baker, J.R.; Vuppusetty, C.; Loukides, S.; Barnes, P.J.; Ito, K. Decreased Serum Sirtuin-1 in COPD. Chest 2017, 152, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pavord, I.D.; Lettis, S.; Locantore, N.; Pascoe, S.; Jones, P.W.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Barnes, N.C. Blood eosinophils and inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting B2 agonist efficacy inCOPD. Thorax 2016, 71, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bozkus, F.; Samur, A.; Yazici, O. Can blood eosinophil count be used as a predictive marker for the severity of COPD and concomitant cardiovascular disease? The relationship with the 2023 Version of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Staging. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 28, 2777–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekström, M.P.; Hermansson, A.B.; Ström, K.E. Effects of cardiovascular drugs on mortality in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo, G.; Pavasini, R.; Biscaglia, S.; Contoli, M.; Ceconi, C. Overview of the pharmacological challenges facing physicians in the management of patients with concomitant cardiovascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2015, 1, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, K.; Lanes, S.; Tave, A.; Pollack, M.F.; Mannino, D.M.; Criner, G.; Neikirk, A.; Rhodes, K.; Feigler, N.; Nordon, C. Risk of Death and Cardiovascular Events Following an Exacerbation of COPD:The EXACOS-CV US Study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2024, 19, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lipson, D.A.; Barnhart, F.; Brealey, N.; Brooks, J.; Criner, G.J.; Day, N.C.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.N.G.; Han, M.K.; Jones, C.E.; et al. IMACT Investigators. Once-Daily Single- Inhaler Triple versus Dual Therapy in Patients with COPD. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1671–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F.J.; Rabe, K.F.; Ferguson, G.T.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Singh, D.; Wang, C.; Rossman, K.; Rose, E.S.; Trivedi, R.; Ballal, S.; et al. Reduced all-cause mortality in the ETHOS trial of budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol for chronic obstructive Pulmonary disease. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, parallel-group Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, D.M.; Decramer, M.; Celli, B.; Kesten, S.; Leimer, I.; Tashkin, D.P. Risk of nonlower respiratory serious adverse events following COPD exacerbations in the 4-year UPLIFT trial. Lung 2011, 189, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rennard, S.I.; Calverley, P.M.; Goehring, U.M.; Bredenbroker, D.; Martinez, F.J. Reduction of exacerbations by the PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast—The importance of defining different subsets of patients with COPD. Respir. Res. 2011, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Li, T.C.; Li, C.I.; Lin, S.P.; Fu, P.K. Statins Associated with Better Long-Term Outcomes in Aged Hospitalized Patients with COPD: A Real-World Experience from Pay-for-Performance Program. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lawes, C.M.; Thornley, S.; Young, R.; Hopkins, R.; Marshall, R.; Chan, W.C.; Jackson, G. Statin use in COPD patients is associated with a reduction in mortality: A National cohort study. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2012, 21, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, Y.; Chang, R.; Yao, J.; Xu, X.; Teng, Y.; Cheng, N. Effectiveness of long-term using statins in COPD—A network meta-analysis. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Neukamm, A.; Høiseth, A.D.; Einvik, G.; Lehmann, S.; Hagve, T.A.; Søyseth, V.; Omland, T. Rosuvastatin treatment in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (RODEO): A randomized controlled trial. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 278, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çolak, Y.; Afzal, S.; Marott, J.L.; Vestbo, J.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Lange, P. Type-2 inflammation and lung function decline in chronic airway disease in the general population. Thorax 2024, 79, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pascoe, S.; Locantore, N.; Dransfield, M.T.; Barnes, N.C.; Pavord, I.D. Blood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomized controlled trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.P.; Rabe, K.F.; Hanania, N.A.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Bafadhel, M.; Christenson, S.A.; Papi, A.; Singh, D.; Laws, E.; Patel, N.; et al. NOTUS Study Investigators Dupilumab for COPD with Blood Eosinophil Evidence of Type 2 Inflammatio. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 2274–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govoni, M.; Bassi, M.; Santoro, D.; Donegan, S.; Singh, D. Serum IL-8 as a Determinant of Response to Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Varricchi, G.; Poto, R. Towards precision medicine in COPD: Targeting type 2 cytokines and alarmins. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 125, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inflammatory Biomarker | Role in COPD | Role in CVD |

|---|---|---|

| CRP | Increased exacerbation risk with decreased lung function | Increased IHD risk |

| Fibrinogen | Increased risk of mortality and exacerbation risk | Higher IHD risk |

| BNP/NT-proBNP | Increased disease activity, exacerbation, and mortality risk | Increased levels in heart failure |

| Troponin | Elevated levels in COPD exacerbation | Detection of myocardial infarction risk |

| VEGF | Higher levels in COPD exacerbation | Predictor of CVD, promoting thrombogenesis |

| Surfactant protein D | Increased risk of exacerbation and all-cause mortality | Increased risk of coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis |

| Galectin-3 | Elevated levels in COPD exacerbation | Related to myocardial fibrosis and remodeling |

| GDF-15 | Associated with sarcopenia, higher exacerbation, and mortality rate | Increased levels in CVD |

| suPAR | Predictor of disease severity, exacerbation, and treatment | Increased levels in CVD |

| Neopterin | Decreased pulmonary function | Related to the risk of cardiovascular events |

| Sirtuin-1 | Reduced expression in COPD patients who smoker | Related to vascular aging and endothelial dysfunction, possible role in IHD |

| Blood eosinophil | Predictor of corticosteroid therapy response in COPD exacerbation | Involved in progression of atherosclerosis |

| ICAM-1 | Decreased pulmonary function | Increased risk of atherogenesis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Valizadeh, M.; Jensen, J.-U.; Ceasovschih, A.; Corlateanu, A.; Sivapalan, P. COPD and Cardiovascular Diseases: Biomarker-Guided Stratification and Therapeutic Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010049

Valizadeh M, Jensen J-U, Ceasovschih A, Corlateanu A, Sivapalan P. COPD and Cardiovascular Diseases: Biomarker-Guided Stratification and Therapeutic Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleValizadeh, Melika, Jens-Ulrik Jensen, Alexandr Ceasovschih, Alexandru Corlateanu, and Pradeesh Sivapalan. 2026. "COPD and Cardiovascular Diseases: Biomarker-Guided Stratification and Therapeutic Perspectives" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010049

APA StyleValizadeh, M., Jensen, J.-U., Ceasovschih, A., Corlateanu, A., & Sivapalan, P. (2026). COPD and Cardiovascular Diseases: Biomarker-Guided Stratification and Therapeutic Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010049