Evolution of Coronary Stents: From Birth to Future Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Searching Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Addressed the design, function, evolution, clinical performance, or translational adoption of coronary or endovascular stents.

- Reported original research, regulatory documentation, expert consensus, or real-world clinical data.

- Contributed meaningfully to the historical, technological and clinical understanding of stents.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Focused exclusively on unrelated cardiovascular implants (e.g., valves, grafts).

- Case reports with anecdotal value only.

- Technical patents without supporting experimental or clinical evaluation.

2.4. Study Selection Process and Potential Selection Bias

3. Historical Development

3.1. Birth of PCI—A Glance into History (-1977)

Cardiac Intervention—A Long Journey

3.2. PTCA to Stent—A New Era (1977–1986)

Stent as Standard of Care

3.3. Amelioration of Stenting—DAPT and Coatings (1986–2002)

3.3.1. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

3.3.2. Stent Coating—A Revolutionary Concept

3.3.3. Biocompatible Coatings—Early Attempt

3.3.4. DES—A Revolutionary Drug-Delivery Coating

4. Current Stent Technologies

4.1. A Rapid Evolution (2002–Now)

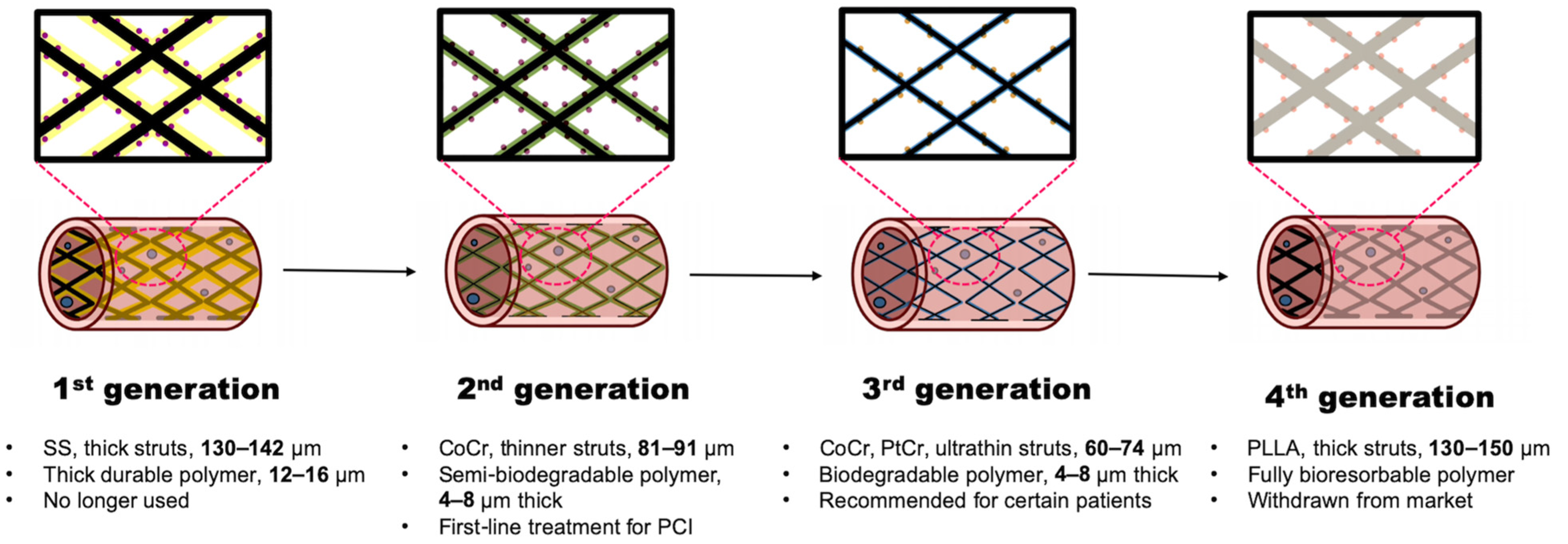

4.1.1. First-Generation DES

4.1.2. Second-Generation DES

4.1.3. Third-Generation DES

4.1.4. Fourth-Generation DES

4.2. Personalized DAPT

5. Future Directions

5.1. Biodegradable Alloy Scaffolds

5.2. Surface Functionalization

5.3. Stimuli-Responsive Coatings

5.4. Biomimetic Coatings

5.5. Integration of Smart and Digital Technologies

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC/AHA | American college of cardiology/American heart association |

| ACS | acute coronary syndromes |

| BMS | bare-metal stent |

| BVS | bioresorbable vascular scaffold |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| CABG | coronary artery bypass grafting |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CoCr | cobalt-chromium |

| DAPT | dual antiplatelet therapy |

| DBCO | dibenzocyclooctyne |

| DES | drug-eluting stent |

| EMA | European medicines agency |

| ESC | European society of cardiology |

| FDA | U.S. food and drug administration |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| ISR | in-stent restenosis |

| LST | late stent thrombosis |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

| NIR | near-infrared |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| PBMA | poly(n-butyl methacrylate) |

| PCI | percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PDA | polydopamine |

| PDLLA | poly(d,l-lactic acid) |

| PEVA | poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate) |

| PLGA | poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PLLA | poly(l-lactide) |

| PtCr | platinum-chromium |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RR | risk ratio |

| SIBS | styrene-isobutylene-styrene |

| SMC | smooth muscle cell |

| SS | stainless steel |

| ST | stent thrombosis |

References

- Stark, B.; Johnson, C.; Roth, G.A. Global prevalence of coronary artery disease: An update from the global burden of disease study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyton, J.R.; Klemp, K.F. Development of the lipid-rich core in human atherosclerosis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996, 16, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 2002, 420, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzon, J.F.; Otsuka, F.; Virmani, R.; Falk, E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1852–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.M.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, J.H. Ten-year trends of clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: A Korean nationwide longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, B.; Ma, Y.; Ma, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Su, X.; Li, B.; et al. Trends in percutaneous coronary intervention in China: Analysis of China PCI Registry Data from 2010 to 2018. Cardiol. Plus 2022, 7, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, S.; Bennett, K.; Shelley, E.; Kearney, P.; Daly, K.; Fennell, W. Trends in percutaneous coronary intervention and angiography in Ireland, 2004-2011: Implications for Ireland and Europe. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vessels 2014, 4, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inohara, T.; Kohsaka, S.; Spertus, J.A.; Masoudi, F.A.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Kennedy, K.F.; Wang, T.Y.; Yamaji, K.; Amano, T.; Nakamura, M. Comparative Trends in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Japan and the United States, 2013 to 2017. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1328–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand View Research, Stents Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Product (Coronary, Peripheral), by Material, by End-Use, by Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2024–2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/stents-market-report (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruntzig, A. Transluminal dilatation of coronary-artery stenosis. Lancet 1978, 311, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentecost, B.L. Coronary artery disease. I. Management of the acute episode. Br. Med. J. 1971, 1, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florey, H. Coronary artery disease. Br. Med. J. 1960, 2, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, F.C.; Glassman, E. Surgical procedures for coronary artery disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 1972, 23, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, H.W., Jr.; Fisher, R.D.; Faulkner, S.L.; Friesinger, G.C. Unstable coronary artery disease: Comparison of medical and surgical treatment. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1975, 19, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monagan, D.; Williams, D.O. Journey into the Heart: A Tale of Pioneering Doctors and Their Race to Transform Cardiovascular Medicine; Gotham Books: Sheridan, WY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Afshar, A.; Steensma, D.P.; Kyle, R.A. Werner Forssmann: A Pioneer of Interventional Cardiology and Auto-Experimentation. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, e97–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1956. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1956/summary/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Shrestha, S.; Patel, J.; Hollander, G.; Shani, J. Coronary Artery Stents: From the Beginning to the Present. Consultant 2020, 60, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, M.J. Tribute to a legend in invasive/interventional cardiology Melvin P. Judkins, M.D. (1922–85). Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2005, 64, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, M.M. Charles Theodore Dotter. The father of intervention. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2001, 28, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barton, M.; Gruntzig, J.; Husmann, M.; Rosch, J. Balloon Angioplasty—The Legacy of Andreas Gruntzig, M.D. (1939–1985). Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2014, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, C.; Aronoff, R. Restenosis following coronary angioplasty. Am. Heart J. 1990, 119, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Popma, J.J.; Ellis, S.G.; Hacker, J.A.; Topol, E.J. Abrupt vessel closure complicating coronary angioplasty: Clinical, angiographic and therapeutic profile. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992, 19, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekar, B.; Tanguay, J.F. Platelets and restenosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 35, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker, L.A. Role of platelets and thrombosis in mechanisms of acute occlusion and restenosis after angioplasty. Am. J. Cardiol. 1987, 60, 20B–28B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruys, P.W.; Luijten, H.E.; Beatt, K.J.; Geuskens, R.; de Feyter, P.J.; van den Brand, M.; Reiber, J.H.; ten Katen, H.J.; van Es, G.A.; Hugenholtz, P.G. Incidence of restenosis after successful coronary angioplasty: A time-related phenomenon. A quantitative angiographic study in 342 consecutive patients at 1, 2, 3, and 4 months. Circulation 1988, 77, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigwart, U. The Stent Story: How it all started. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2171–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigwart, U.; Puel, J.; Mirkovitch, V.; Joffre, F.; Kappenberger, L. Intravascular stents to prevent occlusion and restenosis after transluminal angioplasty. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 316, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmaz, J.C. Balloon-expandable intravascular stent. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1988, 150, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruys, P.W.; Strauss, B.H.; Beatt, K.J.; Bertrand, M.E.; Puel, J.; Rickards, A.F.; Meier, B.; Goy, J.J.; Vogt, P.; Kappenberger, L.; et al. Angiographic follow-up after placement of a self-expanding coronary-artery stent. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, R.F.; Kuntz, R.E.; Carrozza, J.P., Jr.; Miller, M.J.; Senerchia, C.C.; Schnitt, S.J.; Diver, D.J.; Safian, R.D.; Baim, D.S. Long-term results of directional coronary atherectomy: Predictors of restenosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992, 20, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Feuvre, C.; Bonan, R.; Lesperance, J.; Gosselin, G.; Joyal, M.; Crepeau, J. Predictive factors of restenosis after multivessel percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am. J. Cardiol. 1994, 73, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhai, A.; Booth, J.; Delahunty, N.; Nugara, F.; Clayton, T.; McNeill, J.; Davies, S.W.; Cumberland, D.C.; Stables, R.H.; on behalf of the SV Stent Investigators. The SV stent study: A prospective, multicentre, angiographic evaluation of the BiodivYsio phosphorylcholine coated small vessel stent in small coronary vessels. Int. J. Cardiol. 2005, 102, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostoni, P.; Valgimigli, M.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.G.; Abbate, A.; Garcia Garcia, H.M.; Anselmi, M.; Turri, M.; McFadden, E.P.; Vassanelli, C.; Serruys, P.W.; et al. Clinical effectiveness of bare-metal stenting compared with balloon angioplasty in total coronary occlusions: Insights from a systematic overview of randomized trials in light of the drug-eluting stent era. Am. Heart J. 2006, 151, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccheri, D.; Piraino, D.; Andolina, G.; Cortese, B. Understanding and managing in-stent restenosis: A review of clinical data, from pathogenesis to treatment. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E1150–E1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischman, D.L.; Leon, M.B.; Baim, D.S.; Schatz, R.A.; Savage, M.P.; Penn, I.; Detre, K.; Veltri, L.; Ricci, D.; Nobuyoshi, M.; et al. A randomized comparison of coronary-stent placement and balloon angioplasty in the treatment of coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruys, P.W.; de Jaegere, P.; Kiemeneij, F.; Macaya, C.; Rutsch, W.; Heyndrickx, G.; Emanuelsson, H.; Marco, J.; Legrand, V.; Materne, P.; et al. A comparison of balloon-expandable-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, M.J.; Brown, P.P.; Kugelmass, A.D.; Battaglia, S.L.; Tarkington, L.G.; Simon, A.W.; Culler, S.D.; Becker, E.R. Current status and outcomes of coronary revascularization 1999 to 2002: 148,396 surgical and percutaneous procedures. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004, 77, 761–766; discussion 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, F.C.; Muller, D.W.; Ellis, S.G.; Rosenschein, U.; Chapekis, A.; Quain, L.; Zimmerman, C.; Topol, E.J. Thrombosis of a flexible coil coronary stent: Frequency, predictors and clinical outcome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1993, 21, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzalini, L.; Ellis, S.G.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Kimura, T.; Gao, R.; Onuma, Y.; Chevalier, B.; Dressler, O.; Crowley, A.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Optimal dual antiplatelet therapy duration for bioresorbable scaffolds: An individual patient data pooled analysis of the ABSORB trials. EuroIntervention 2021, 17, e981–e988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Feyter, P.J.; DeScheerder, I.; van den Brand, M.; Laarman, G.; Suryapranata, H.; Serruys, P.W. Emergency stenting for refractory acute coronary artery occlusion during coronary angioplasty. Am. J. Cardiol. 1990, 66, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis-Gravel, G.; Dalgaard, F.; Jones, A.D.; Lokhnygina, Y.; James, S.K.; Harrington, R.A.; Wallentin, L.; Steg, P.G.; Lopes, R.D.; Storey, R.F.; et al. Post-Discharge Bleeding and Mortality Following Acute Coronary Syndromes With or Without PCI. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, L.; Afzal, S.; Czychy, N.; M’Pembele, R.; Zako, S.; Helten, C.; Mourikis, P.; Zikeli, D.; Ahlbrecht, S.; Trojovsky, K.; et al. Risk prediction of bleeding and MACCE by PRECISE-DAPT score post-PCI. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2021, 33, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunther, H.U.; Strupp, G.; Volmar, J.; von Korn, H.; Bonzel, T.; Stegmann, T. Coronary stent implantation: Infection and abscess with fatal outcome. Z. Kardiol. 1993, 82, 521–525. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, B.A.; Kaiser, C.; Pfisterer, M.E.; Bonetti, P.O. Coronary stent infection: A rare but severe complication of percutaneous coronary intervention. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2005, 135, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubelakis, A.; Rawlins, J.; Baliulis, G.; Olsen, S.; Corbett, S.; Kaarne, M.; Curzen, N. Coronary artery rupture caused by stent infection: A rare complication. Circulation 2015, 131, 1302–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, E.; Kostantinis, S.; Karacsonyi, J.; Allana, S.S.; Walser-Kuntz, E.; Rangan, B.V.; Simsek, B.; Rynders, B.; Mastrodemos, O.C.; Stanberry, L.; et al. Incidence, treatment and outcomes of coronary artery dissection during percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2023, 35, E341–E354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, V.M.; Mintz, G.S.; Apple, S.; Weissman, N.J. Background incidence of late malapposition after bare-metal stent implantation. Circulation 2002, 106, 1753–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.K.; Mintz, G.S.; Lee, C.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, S.W.; Song, J.M.; Han, K.H.; Kang, D.H.; Song, J.K.; Kim, J.J.; et al. Incidence, mechanism, predictors, and long-term prognosis of late stent malapposition after bare-metal stent implantation. Circulation 2004, 109, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, A.; Hall, P.; Nakamura, S.; Almagor, Y.; Maiello, L.; Martini, G.; Gaglione, A.; Goldberg, S.L.; Tobis, J.M. Intracoronary stenting without anticoagulation accomplished with intravascular ultrasound guidance. Circulation 1995, 91, 1676–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schomig, A.; Neumann, F.J.; Kastrati, A.; Schuhlen, H.; Blasini, R.; Hadamitzky, M.; Walter, H.; Zitzmann-Roth, E.M.; Richardt, G.; Alt, E.; et al. A randomized comparison of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy after the placement of coronary-artery stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.R.; Yusuf, S.; Peters, R.J.; Bertrand, M.E.; Lewis, B.S.; Natarajan, M.K.; Malmberg, K.; Rupprecht, H.; Zhao, F.; Chrolavicius, S.; et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: The PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001, 358, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steg, P.G.; Harrington, R.A.; Emanuelsson, H.; Katus, H.A.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Meier, B.; Storey, R.F.; Wojdyla, D.M.; Lewis, B.S.; Maurer, G.; et al. Stent thrombosis with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: An analysis from the prospective, randomized PLATO trial. Circulation 2013, 128, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, J.P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthélémy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Dendale, P.; Dorobantu, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Folliguet, T.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1289–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Morimoto, T.; Natsuaki, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Obayashi, Y.; Ogita, M.; Suwa, S.; Isawa, T.; Domei, T.; Yamaji, K.; et al. Comparison of Clopidogrel Monotherapy After 1 to 2 Months of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy with 12 Months of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: The STOPDAPT-2 ACS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Vranckx, P.; Valgimigli, M.; Sartori, S.; Angiolillo, D.J.; Bangalore, S.; Bhatt, D.L.; Feng, Y.; Ge, J.; Hermiller, J.; et al. One- versus three-month dual antiplatelet therapy in high bleeding risk patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. EuroIntervention 2024, 20, e630–e642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Mitsumata, M.; Ling, G.; Jiang, J.; Shu, Q. Migration of medial smooth muscle cells to the intima after balloon injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997, 811, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, J.S.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Bangalore, S.; Bates, E.R.; Beckie, T.M.; Bischoff, J.M.; Bittl, J.A.; Cohen, M.G.; DiMaio, J.M.; Don, C.W.; et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization. JACC 2022, 79, e21–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, H.; Weiss, A.B.; Parsons, J.R. Ligament and tendon repair with an absorbable polymer-coated carbon fiber stent. Bull. Hosp. Jt. Dis. Orthop. Inst. 1986, 46, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- George, P.J.; Irving, J.D.; Mantell, B.S.; Rudd, R.M. Covered expandable metal stent for recurrent tracheal obstruction. Lancet 1990, 335, 582–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, R.; Palmaz, J.C.; Garcia, O.J.; Tio, F.O.; Rees, C.R. Evaluation of polymer-coated balloon-expandable stents in bile ducts. Radiology 1989, 170, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, T.; Robich, M.P. Drug-eluting stent coatings. Interv. Cardiol. 2012, 4, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.; Sevilla, P.; Galan, A.M.; Escolar, G.; Engel, E.; Gil, F.J. Evaluation of ion release, cytotoxicity, and platelet adhesion of electrochemical anodized 316 L stainless steel cardiovascular stents. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2008, 87, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanekamp, C.E.; Bonnier, H.J.; Michels, R.H.; Peels, K.H.; Heijmen, E.P.; Hagen Ev, E.; Koolen, J.J. Initial results and long-term clinical follow-up of an amorphous hydrogenated silicon-carbide-coated stent in daily practice. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Interv. 1998, 1, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehrlein, C.; Zimmermann, M.; Metz, J.; Ensinger, W.; Kubler, W. Influence of surface texture and charge on the biocompatibility of endovascular stents. Coron. Artery Dis. 1995, 6, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holmes, D.R.; Camrud, A.R.; Jorgenson, M.A.; Edwards, W.D.; Schwartz, R.S. Polymeric stenting in the porcine coronary artery model: Differential outcome of exogenous fibrin sleeves versus polyurethane-coated stents. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994, 24, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, C.D.; Lee, E.S.; Kim, S.W. The antiplatelet activity of immobilized prostacyclin. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1982, 16, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardhammar, P.A.; van Beusekom, H.M.; Emanuelsson, H.U.; Hofma, S.H.; Albertsson, P.A.; Verdouw, P.D.; Boersma, E.; Serruys, P.W.; van der Giessen, W.J. Reduction in thrombotic events with heparin-coated Palmaz-Schatz stents in normal porcine coronary arteries. Circulation 1996, 93, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beusekom, H.M.; Serruys, P.W.; van der Giessen, W.J. Coronary stent coatings. Coron. Artery Dis. 1994, 5, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, C.J.; Camrud, A.R.; Sangiorgi, G.; Kwon, H.M.; Edwards, W.D.; Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Schwartz, R.S. Fibrin-film stenting in a porcine coronary injury model: Efficacy and safety compared with uncoated stents. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998, 31, 1434–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelsson, H.; van der Giessen, W.J.; Serruys, P.W. Benestent II: Back to the future. J. Interv. Cardiol. 1994, 7, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unverdorben, M.; Sippel, B.; Degenhardt, R.; Sattler, K.; Fries, R.; Abt, B.; Wagner, E.; Koehler, H.; Daemgen, G.; Scholz, M.; et al. Comparison of a silicon carbide-coated stent versus a noncoated stent in human beings: The Tenax versus Nir Stent Study’s long-term outcome. Am. Heart J. 2003, 145, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, S.; Kornowski, R.; Silber, S.; Lewis, B.S.; Bilodeau, L.; Almagor, Y.; van Remortel, E.; Morice, M.C.; Colombo, A. Fused-Gold’ vs. ‘Bare’ stainless steel NIRflex stents of the same geometric design in diseased native coronary arteries. Long-term results from the NIR TOP Study. EuroIntervention 2007, 3, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Furst, J.G.; Ellis, S.G.; Tuch, R.J.; Topol, E.J. Sustained local delivery of dexamethasone by a novel intravascular eluting stent to prevent restenosis in the porcine coronary injury model. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997, 29, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regar, E.; Sianos, G.; Serruys, P.W. Stent development and local drug delivery. Br. Med. Bull. 2001, 59, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruys, P.W.; Ormiston, J.A.; Sianos, G.; Sousa, J.E.; Grube, E.; den Heijer, P.; de Feyter, P.; Buszman, P.; Schomig, A.; Marco, J.; et al. Actinomycin-eluting stent for coronary revascularization: A randomized feasibility and safety study: The ACTION trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 1363–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, J.H., Jr.; McCallister, B.D.; Bateman, T.M.; Kuhnlein, D.L.; Ligon, R.W.; Hartzler, G.O. Ineffectiveness of colchicine for the prevention of restenosis after coronary angioplasty. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992, 19, 1597–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, M.; Marx, S.O.; Gallo, R.; Badimon, J.J.; Taubman, M.B.; Marks, A.R. Rapamycin inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell migration. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 98, 2277–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axel, D.I.; Kunert, W.; Goggelmann, C.; Oberhoff, M.; Herdeg, C.; Kuttner, A.; Wild, D.H.; Brehm, B.R.; Riessen, R.; Koveker, G.; et al. Paclitaxel inhibits arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration in vitro and in vivo using local drug delivery. Circulation 1997, 96, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J.W.; Leon, M.B.; Popma, J.J.; Fitzgerald, P.J.; Holmes, D.R.; O’Shaughnessy, C.; Caputo, R.P.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Williams, D.O.; Teirstein, P.S.; et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W.; Ellis, S.G.; Cox, D.A.; Hermiller, J.; O’Shaughnessy, C.; Mann, J.T.; Turco, M.; Caputo, R.; Bergin, P.; Greenberg, J.; et al. One-year clinical results with the slow-release, polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting TAXUS stent: The TAXUS-IV trial. Circulation 2004, 109, 1942–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, L.T.; Kutcher, M.A.; Royster, R.L. Coronary artery stents: Part I. Evolution of percutaneous coronary intervention. Anesth. Analg. 2008, 107, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, E.P.; Stabile, E.; Regar, E.; Cheneau, E.; Ong, A.T.; Kinnaird, T.; Suddath, W.O.; Weissman, N.J.; Torguson, R.; Kent, K.M.; et al. Late thrombosis in drug-eluting coronary stents after discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy. Lancet 2004, 364, 1519–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, A.J.; Briel, M.; Bucher, H.C. Mortality in randomized controlled trials comparing drug-eluting vs. bare metal stents in coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 2784–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerqvist, B.; Carlsson, J.; Frobert, O.; Lindback, J.; Schersten, F.; Stenestrand, U.; James, S.K.; Swedish Coronary, A.; Angioplasty Registry Study, G. Stent thrombosis in Sweden: A report from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camenzind, E.; Steg, P.G.; Wijns, W. Stent thrombosis late after implantation of first-generation drug-eluting stents: A cause for concern. Circulation 2007, 115, 1440–1455; discussion 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brami, P.; Fischer, Q.; Pham, V.; Seret, G.; Varenne, O.; Picard, F. Evolution of Coronary Stent Platforms: A Brief Overview of Currently Used Drug-Eluting Stents. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, C.; Pfisterer, M. Increased rate of stent thrombosis with DES. Herz 2007, 32, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, L.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Yeh, R.W.; Driscoll-Shempp, P.; Cutlip, D.E.; Steg, P.G.; Normand, S.L.; Braunwald, E.; Wiviott, S.D.; Cohen, D.J.; et al. Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2155–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W.; Ellis, S.G.; Cox, D.A.; Hermiller, J.; O’Shaughnessy, C.; Mann, J.T.; Turco, M.; Caputo, R.; Bergin, P.; Greenberg, J.; et al. A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, R.M.; Abbott, J.D. Update on the everolimus-eluting coronary stent system: Results and implications from the SPIRIT clinical trial program. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H.; Chung, W.Y.; Lee, J.M.; Park, J.J.; Yoon, C.H.; Suh, J.W.; Cho, Y.S.; Doh, J.H.; Cho, J.M.; Bae, J.W.; et al. Angiographic outcomes of Orsiro biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stents and Resolute Integrity durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stents: Results of the ORIENT trial. EuroIntervention 2017, 12, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, I.T.; Verheye, S.; Dubois, C.L.; Dens, J.; Fajadet, J.; Carrie, D.; Walsh, S.; Oldroyd, K.G.; Varenne, O.; El-Jack, S.; et al. Primary endpoint results of the EVOLVE trial: A randomized evaluation of a novel bioabsorbable polymer-coated, everolimus-eluting coronary stent. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diletti, R.; Serruys, P.W.; Farooq, V.; Sudhir, K.; Dorange, C.; Miquel-Hebert, K.; Veldhof, S.; Rapoza, R.; Onuma, Y.; Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; et al. ABSORB II randomized controlled trial: A clinical evaluation to compare the safety, efficacy, and performance of the Absorb everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold system against the XIENCE everolimus-eluting coronary stent system in the treatment of subjects with ischemic heart disease caused by de novo native coronary artery lesions: Rationale and study design. Am. Heart J. 2012, 164, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitabata, H.; Kubo, T.; Komukai, K.; Ishibashi, K.; Tanimoto, T.; Ino, Y.; Takarada, S.; Ozaki, Y.; Kashiwagi, M.; Orii, M.; et al. Effect of strut thickness on neointimal atherosclerotic change over an extended follow-up period (>/= 4 years) after bare-metal stent implantation: Intracoronary optical coherence tomography examination. Am. Heart J. 2012, 163, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapnisis, K.; Constantinides, G.; Georgiou, H.; Cristea, D.; Gabor, C.; Munteanu, D.; Brott, B.; Anderson, P.; Lemons, J.; Anayiotos, A. Multi-scale mechanical investigation of stainless steel and cobalt-chromium stents. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 40, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedhi, E.; Joesoef, K.S.; McFadden, E.; Wassing, J.; van Mieghem, C.; Goedhart, D.; Smits, P.C. Second-generation everolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in real-life practice (COMPARE): A randomised trial. Lancet 2010, 375, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Chico, J.L.; van Geuns, R.J.; Regar, E.; van der Giessen, W.J.; Kelbæk, H.; Saunamäki, K.; Escaned, J.; Gonzalo, N.; di Mario, C.; Borgia, F.; et al. Tissue coverage of a hydrophilic polymer-coated zotarolimus-eluting stent vs. a fluoropolymer-coated everolimus-eluting stent at 13-month follow-up: An optical coherence tomography substudy from the RESOLUTE All Comers trial. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 2454–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, D.; Ploumen, E.H.; Pinxterhuis, T.H.; Buiten, R.A.; Aminian, A.; Schotborgh, C.E.; Danse, P.W.; Roguin, A.; Anthonio, R.L.; Benit, E.; et al. Final 5-year report of BIONYX comparing the thin-composite wire-strut zotarolimus-eluting stent versus ultrathin-strut sirolimus-eluting stent. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 104, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, E.; Byrne, R.A.; Kastrati, A. Pharmacological inhibition of coronary restenosis: Systemic and local approaches. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2014, 15, 2155–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKeigan, J.P.; Krueger, D.A. Differentiating the mTOR inhibitors everolimus and sirolimus in the treatment of tuberous sclerosis complex. Neuro Oncol. 2015, 17, 1550–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.W.; Lee, J.M.; Kang, S.H.; Ahn, H.S.; Yang, H.M.; Lee, H.Y.; Kang, H.J.; Koo, B.K.; Cho, J.; Gwon, H.C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of second-generation everolimus-eluting Xience V stents versus zotarolimus-eluting resolute stents in real-world practice: Patient-related and stent-related outcomes from the multicenter prospective EXCELLENT and RESOLUTE-Korea registries. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Birgelen, C.; Basalus, M.W.; Tandjung, K.; van Houwelingen, K.G.; Stoel, M.G.; Louwerenburg, J.H.; Linssen, G.C.; Said, S.A.; Kleijne, M.A.; Sen, H.; et al. A randomized controlled trial in second-generation zotarolimus-eluting Resolute stents versus everolimus-eluting Xience V stents in real-world patients: The TWENTE trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 1350–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Birgelen, C.; Sen, H.; Lam, M.K.; Danse, P.W.; Jessurun, G.A.; Hautvast, R.W.; van Houwelingen, G.K.; Schramm, A.R.; Gin, R.M.; Louwerenburg, J.W.; et al. Third-generation zotarolimus-eluting and everolimus-eluting stents in all-comer patients requiring a percutaneous coronary intervention (DUTCH PEERS): A randomised, single-blind, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.J.; Marks, A.; Berg, K.J.; Eppihimer, M.; Sushkova, N.; Hawley, S.P.; Robertson, K.A.; Knapp, D.; Pennington, D.E.; Chen, Y.L.; et al. The SYNERGY biodegradable polymer everolimus eluting coronary stent: Porcine vascular compatibility and polymer safety study. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 86, E247–E257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kereiakes, D.J.; Windecker, S.; Jobe, R.L.; Mehta, S.R.; Sarembock, I.J.; Feldman, R.L.; Stein, B.; Dubois, C.; Grady, T.; Saito, S.; et al. Clinical Outcomes Following Implantation of Thin-Strut, Bioabsorbable Polymer-Coated, Everolimus-Eluting SYNERGY Stents. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, e008152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, M.M.; Zocca, P.; Buiten, R.A.; Danse, P.W.; Schotborgh, C.E.; Scholte, M.; Hartmann, M.; Stoel, M.G.; van Houwelingen, G.; Linssen, G.C.M.; et al. Two-year clinical outcome of all-comers treated with three highly dissimilar contemporary coronary drug-eluting stents in the randomised BIO-RESORT trial. EuroIntervention 2018, 14, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilgrim, T.; Heg, D.; Roffi, M.; Tuller, D.; Muller, O.; Vuilliomenet, A.; Cook, S.; Weilenmann, D.; Kaiser, C.; Jamshidi, P.; et al. Ultrathin strut biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent versus durable polymer everolimus-eluting stent for percutaneous coronary revascularisation (BIOSCIENCE): A randomised, single-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2014, 384, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Way, J.A.H.; Kritharides, L.; Brieger, D. Polymer-free versus durable polymer drug-eluting stents in patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Ann. Med. Surg. 2019, 38, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastrati, A.; Mehilli, J.; Dirschinger, J.; Dotzer, F.; Schuhlen, H.; Neumann, F.J.; Fleckenstein, M.; Pfafferott, C.; Seyfarth, M.; Schomig, A. Intracoronary stenting and angiographic results: Strut thickness effect on restenosis outcome (ISAR-STEREO) trial. Circulation 2001, 103, 2816–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, H.Y.; Huang, Y.Y.; Lim, S.T.; Wong, P.; Joner, M.; Foin, N. Mechanical behavior of polymer-based vs. metallic-based bioresorbable stents. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, S923–S934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizing, E.; Kum, S.; Ipema, J.; Varcoe, R.L.; Shah, A.P.; de Vries, J.P.; Unlu, C. Mid-term outcomes of an everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold in patients with below-the-knee arterial disease: A pooled analysis of individual patient data. Vasc. Med. 2021, 26, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, S.; Sartori, S.; Baber, U.; Claessen, B.E.; Giustino, G.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Chandiramani, R.; Cohen, D.J.; Henry, T.D.; Guedeney, P.; et al. Bleeding Risk, Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Cessation, and Adverse Events After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The PARIS Registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, e008226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, Y.; Bar, S.; Losdat, S.; Otsuka, T.; Zanchin, C.; Zanchin, T.; Gragnano, F.; Gargiulo, G.; Siontis, G.C.M.; Praz, F.; et al. Validation of the Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk (ARC-HBR) criteria in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and comparison with contemporary bleeding risk scores. EuroIntervention 2020, 16, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtane, A.J.; Stoler, R.; Feldman, R.; Neumann, F.J.; Boutis, L.; Tahirkheli, N.; Toelg, R.; Othman, I.; Stein, B.; Choi, J.W.; et al. Primary Results of the EVOLVE Short DAPT Study: Evaluation of 3-Month Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in High Bleeding Risk Patients Treated with a Bioabsorbable Polymer-Coated Everolimus-Eluting Stent. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, e010144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, F.; Hort, N.; Vogt, C.; Cohen, S.; Kainer, K.U.; Willumeit, R.; Feyerabend, F. Degradable biomaterials based on magnesium corrosion. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2008, 12, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zheng, M.Y. Effects of microarc oxidation surface treatment on the mechanical properties of Mg alloy and Mg matrix composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 447, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haude, M.; Toelg, R.; Lemos, P.A.; Christiansen, E.H.; Abizaid, A.; von Birgelen, C.; Neumann, F.J.; Wijns, W.; Ince, H.; Kaiser, C.; et al. Sustained Safety and Performance of a Second-Generation Sirolimus-Eluting Absorbable Metal Scaffold: Long-Term Data of the BIOSOLVE-II First-in-Man Trial at 5 Years. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2022, 38, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksman, R.; Erbel, R.; Di Mario, C.; Bartunek, J.; de Bruyne, B.; Eberli, F.R.; Erne, P.; Haude, M.; Horrigan, M.; Ilsley, C.; et al. Early- and long-term intravascular ultrasound and angiographic findings after bioabsorbable magnesium stent implantation in human coronary arteries. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksman, R.; Pakala, R.; Kuchulakanti, P.K.; Baffour, R.; Hellinga, D.; Seabron, R.; Tio, F.O.; Wittchow, E.; Hartwig, S.; Harder, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of bioabsorbable magnesium alloy stents in porcine coronary arteries. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2006, 68, 607–617; discussion 618–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, M.; Vaz, M.F.; Colaco, R.; Santos, C.; Carmezim, M. Biodegradable Iron and Porous Iron: Mechanical Properties, Degradation Behaviour, Manufacturing Routes and Biomedical Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaed, E.; Sikora-Jasinska, M.; Drelich, J.W.; Vedani, M. Zinc-based alloys for degradable vascular stent applications. Acta Biomater. 2018, 71, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venezuela, J.; Dargusch, M.S. The influence of alloying and fabrication techniques on the mechanical properties, biodegradability and biocompatibility of zinc: A comprehensive review. Acta Biomater. 2019, 87, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, K.; Gao, J.; Yang, Y.; Qin, Y.X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, D. Enhanced cytocompatibility and antibacterial property of zinc phosphate coating on biodegradable zinc materials. Acta Biomater. 2019, 98, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hast, K.; Stone, M.R.L.; Jia, Z.; Baci, M.; Aggarwal, T.; Izgu, E.C. Bioorthogonal Functionalization of Material Surfaces with Bioactive Molecules. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 4996–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Dellatore, S.M.; Miller, W.M.; Messersmith, P.B. Mussel-inspired surface chemistry for multifunctional coatings. Science 2007, 318, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Jin, Q.; Ren, K.; Ji, J. Mussel-inspired polydopamine: A biocompatible and ultrastable coating for nanoparticles in vivo. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9384–9395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Wilson, R.L. Polydopamine Applications in Biomedicine and Environmental Science. Materials 2024, 17, 3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Nie, J.; Xu, L.; Liang, C.; Peng, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, T.; Mei, L.; Huang, L.; Zeng, X. pH-Sensitive Delivery Vehicle Based on Folic Acid-Conjugated Polydopamine-Modified Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Targeted Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 18462–18473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, A.P.; Bhattarai, D.P.; Maharjan, B.; Ko, S.W.; Kim, H.Y.; Park, C.H.; Kim, C.S. Polydopamine-based Implantable Multifunctional Nanocarpet for Highly Efficient Photothermal-chemo Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, B.; Guo, G.; Yu, T.; Yang, L.; Li, G.; Luo, R.; Wang, Y. Research and prospects of strategies for surface-modified coatings on blood-contacting materials. Med-X 2025, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2022: Fulfilling Demanding Applications with Simple Reactions. ACS Chem. Biol. 2022, 17, 2959–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chu, C.W.; Ma, W.; Takahara, A. Functionalization of Metal Surface via Thiol-Ene Click Chemistry: Synthesis, Adsorption Behavior, and Postfunctionalization of a Catechol- and Allyl-Containing Copolymer. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 7488–7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Hao, R.; Tu, Q.; Tian, X.; Xiao, Y.; Xiong, K.; Wang, M.; Feng, Y.; Huang, N.; et al. Bioclickable and mussel adhesive peptide mimics for engineering vascular stent surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 16127–16137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Wang, T.; Li, F.; Mao, X. Surface modifications of biomaterials in different applied fields. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 20495–20511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspardone, A.; Versaci, F. Coronary stenting and inflammation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 65L–70L. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Wu, L.; Liu, X.; Jiao, Z. A facile route for rapid synthesis of hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles as pH-responsive delivery carrier. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 451, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Zhuang, W.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y. A biomimetic and pH-sensitive polymeric micelle as carrier for paclitaxel delivery. Regen. Biomater. 2017, 5, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Kulkarni, P.P.; Tripathi, P.; Agarwal, V.; Dash, D. Nanogold-coated stent facilitated non-invasive photothermal ablation of stent thrombosis and restoration of blood flow. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, W.; Niu, C.; Yu, G.; Huang, X.; Shi, J.; Ma, D.; Lin, X.; Zhao, K. A NIR light-activated PLGA microsphere for controlled release of mono- or dual-drug. Polym. Test. 2022, 116, 107762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, G.M.; Small, W.t.; Wilson, T.S.; Benett, W.J.; Matthews, D.L.; Hartman, J.; Maitland, D.J. Fabrication and in vitro deployment of a laser-activated shape memory polymer vascular stent. Biomed. Eng. Online 2007, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moris, D.; Spartalis, M.; Spartalis, E.; Karachaliou, G.S.; Karaolanis, G.I.; Tsourouflis, G.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Tzatzaki, E.; Theocharis, S. The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases and the clinical significance of myocardial redox. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Shang, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, L.; Liu, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Application of a Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Drug-Eluting Coating for Surface Modification of Vascular Stents. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 35431–35443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, R.; Du, Y.; Mou, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y. Reactive oxygen species-responsive coating based on Ebselen: Antioxidation, pro-endothelialization and anti-hyperplasia for surface modification of cardiovascular stent. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 245, 114314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udriste, A.S.; Burdusel, A.C.; Niculescu, A.G.; Radulescu, M.; Grumezescu, A.M. Coatings for Cardiovascular Stents-An Up-to-Date Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Rodriguez, S.; Rasser, C.; Mesnier, J.; Chevallier, P.; Gallet, R.; Choqueux, C.; Even, G.; Sayah, N.; Chaubet, F.; Nicoletti, A.; et al. Coronary stent CD31-mimetic coating favours endothelialization and reduces local inflammation and neointimal development in vivo. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senemaud, J.; Skarbek, C.; Hernandez, B.; Song, R.; Lefevre, I.; Bianchi, E.; Castier, Y.; Nicoletti, A.; Bureau, C.; Caligiuri, G. Camouflaging endovascular stents with an endothelial coat using CD31 domain 1 and 2 mimetic peptides. JVS Vasc. Sci. 2024, 5, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Weng, Y. Copper-Based SURMOFs for Nitric Oxide Generation: Hemocompatibility, Vascular Cell Growth, and Tissue Response. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 7872–7883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Qi, P.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Tan, X.; Xiao, Y.; Maitz, M.F.; Huang, N.; Yang, Z. Biomimetic engineering endothelium-like coating on cardiovascular stent through heparin and nitric oxide-generating compound synergistic modification strategy. Biomaterials 2019, 207, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musick, K.M.; Coffey, A.C.; Irazoqui, P.P. Sensor to detect endothelialization on an active coronary stent. Biomed. Eng. Online 2010, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, E.Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Beier, B.; Chappell, W.J.; Irazoqui, P.P. Evaluation of Cardiovascular Stents as Antennas for Implantable Wireless Applications. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2009, 57, 2523–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brox, D.S.; Chen, X.; Mirabbasi, S.; Takahata, K. Wireless Telemetry of Stainless-Steel-Based Smart Antenna Stent Using a Transient Resonance Method. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2016, 15, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.; Park, I. Ultrathin, Biocompatible, and Flexible Pressure Sensor with a Wide Pressure Range and Its Biomedical Application. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yu, K.; Tan, Y. Applications and Advances of Magnetoelastic Sensors in Biomedical Engineering: A Review. Materials 2019, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.R.; Kwon, R.S.; Elta, G.H.; Gianchandani, Y.B. In situ and ex vivo evaluation of a wireless magnetoelastic biliary stent monitoring system. Biomed. Microdevices 2010, 12, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, J.; Manivasagam, G. Perspectives on smart stents with sensors: From conventional permanent to novel bioabsorbable smart stent technologies. Med. Devices Sens. 2020, 3, e10116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, R.; Lim, H.R.; Rigo, B.; Yeo, W.H. Fully implantable wireless batteryless vascular electronics with printed soft sensors for multiplex sensing of hemodynamics. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The BARI Investigators. The final 10-year follow-up results from the BARI randomized trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 1600–1606. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlatky, M.A. Analysis of costs associated with CABG and PTCA. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1996, 61, S30–S32; discussion S33–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviniemi, T.O.; Pietila, A.; Gunn, J.M.; Aittokallio, J.M.; Mahonen, M.Q.; Salomaa, V.V.; Niiranen, T.J. Trends in rates, patient selection and prognosis of coronary revascularisations in Finland between 1994 and 2013: The CVDR. EuroIntervention 2016, 12, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, N.; Asano, R.; Nagayama, M.; Tobaru, T.; Misu, K.; Hasumi, E.; Hosoya, Y.; Iguchi, N.; Aikawa, M.; Watanabe, H.; et al. Long-term outcome of first-generation metallic coronary stent implantation in patients with coronary artery disease: Observational study over a decade. Circ. J. 2007, 71, 1360–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagerqvist, B.; James, S.K.; Stenestrand, U.; Lindback, J.; Nilsson, T.; Wallentin, L.; Group, S.S. Long-term outcomes with drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in Sweden. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.O.; Tilsted, H.H.; Thayssen, P.; Kaltoft, A.; Maeng, M.; Lassen, J.F.; Hansen, K.N.; Madsen, M.; Ravkilde, J.; Johnsen, S.P.; et al. Paclitaxel and sirolimus eluting stents versus bare metal stents: Long-term risk of stent thrombosis and other outcomes. From the Western Denmark Heart Registry. EuroIntervention 2010, 5, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajadet, J.; Wijns, W.; Laarman, G.J.; Kuck, K.H.; Ormiston, J.; Baldus, S.; Hauptmann, K.E.; Suttorp, M.J.; Drzewiecki, J.; Pieper, M.; et al. Long-term follow-up of the randomised controlled trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the zotarolimus-eluting driver coronary stent in de novo native coronary artery lesions: Five year outcomes in the ENDEAVOR II study. EuroIntervention 2010, 6, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, R.W. Drug-eluting coronary stents—A note of caution. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 186, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baschet, L.; Bourguignon, S.; Marque, S.; Durand-Zaleski, I.; Teiger, E.; Wilquin, F.; Levesque, K. Cost-effectiveness of drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Open Heart 2016, 3, e000445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, T.; Sotomi, Y.; Tsujimura, T.; Iida, O.; Kobayashi, T.; Hamanaka, Y.; Omatsu, T.; Sakata, Y.; Higuchi, Y.; Mano, T. Impact of diabetes mellitus on the early-phase arterial healing after drug-eluting stent implantation. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhammar, A.; Lagerqvist, B.; Saleh, N. Long-term mortality after PCI in patients with diabetes mellitus: Results from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry. EuroIntervention 2010, 5, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Serruys, P.W.; Gao, C.; Hara, H.; Takahashi, K.; Ono, M.; Kawashima, H.; O’leary, N.; Holmes, D.R.; Witkowski, A.; et al. Ten-year all-cause death after percutaneous or surgical revascularization in diabetic patients with complex coronary artery disease. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 43, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elezi, S.; Kastrati, A.; Neumann, F.J.; Hadamitzky, M.; Dirschinger, J.; Schomig, A. Vessel size and long-term outcome after coronary stent placement. Circulation 1998, 98, 1875–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habara, S.; Mitsudo, K.; Goto, T.; Kadota, K.; Fujii, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Kato, H.; Takenaka, S.; Fuku, Y.; Hosogi, S.; et al. The impact of lesion length and vessel size on outcomes after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation for in-stent restenosis. Heart 2008, 94, 1162–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.K.; Park, Y.H.; Song, Y.B.; Oh, J.H.; Chun, W.J.; Kang, G.H.; Jang, W.J.; Hahn, J.Y.; Yang, J.H.; Choi, S.H.; et al. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of True and Non-True Bifurcation Lesions According to Medina Classification- Results From the COBIS (COronary BIfurcation Stent) II Registry. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oemrawsingh, P.V.; Mintz, G.S.; Schalij, M.J.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Jukema, J.W.; van der Wall, E.E. Intravascular ultrasound guidance improves angiographic and clinical outcome of stent implantation for long coronary artery stenoses: Final results of a randomized comparison with angiographic guidance (TULIP Study). Circulation 2003, 107, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valgimigli, M.; Frigoli, E.; Heg, D.; Tijssen, J.; Jüni, P.; Vranckx, P.; Ozaki, Y.; Morice, M.C.; Chevalier, B.; Onuma, Y.; et al. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy after PCI in Patients at High Bleeding Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1643–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, P.; Meredith, I.T.; Abizaid, A.; Pocock, S.J.; Carrié, D.; Naber, C.; Lipiecki, J.; Richardt, G.; Iñiguez, A.; Brunel, P.; et al. Polymer-free Drug-Coated Coronary Stents in Patients at High Bleeding Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2038–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Coronary Drug-Eluting Stents—Nonclinical and Clinical Studies; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2008.

- McDermott, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Hu, X.; Ash-Shakoor, A.; Avery, R.; Belyaeva, A.; Cruz, C.; Hughes, M.; Leadbetter, J.; Merkle, C.; et al. Application of quality by design (QbD) approach to ultrasonic atomization spray coating of drug-eluting stents. AAPS PharmSciTech 2015, 16, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maluenda, G.; Lemesle, G.; Waksman, R. A critical appraisal of the safety and efficacy of drug-eluting stents. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 85, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Serruys, P.W. Coronary stents: Current status. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, S1–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.P.; Yusuf, R.; Iqbal, R.; Avezum, Á.; Yusufali, A.; Rosengren, A.; Chifamba, J.; Lanas, F.; Diaz, M.L.; Miranda, J.J.; et al. The burden of cardiovascular events according to cardiovascular risk profile in adults from high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): A cohort study. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e1406–e1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Complication | Incidence Rate | Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stent Thrombosis | 12–20% (no DAPT) <1–4% (with DAPT) | High morbidity and mortality; often leads to MI or sudden cardiac death. | [33,39,40,42,43,44] |

| In-Stent Restenosis | 17–41% (SS-based BMS) 2.5–5% (New generation DES) | Typically presents as recurrent angina; may require repeat revascularization procedures. | [36,37,38] |

| Bleeding | 2–3% | Increased risk of hemorrhagic events, including gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia. | [45,46] |

| Stent Infection | <0.1% | High mortality; often requires urgent intervention but is frequently fatal. | [47,48,49] |

| Coronary Artery Dissection | 1–2% | Can lead to acute vessel closure; severe cases may require emergency CABG. | [50] |

| Late Stent Malapposition | 4–5% | Potential cause of late restenosis or thrombosis; may necessitate further intervention. | [51,52] |

| Generation | Name | Manufacturer | Material | Strut Thickness (µm) | Polymer Type | Polymer Thickness (µm) | Drug | Drug Release Kinetics | Late Lumen Loss (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Cypher | Cordis | SS | 140 | Durable (PEVA/PBMA) | 12.6 | Sirolimus | 80% in 30 days | 0.17–0.24 [84] |

| Taxus | Boston Scientific | SS | 132 | Durable (SIBS) | 16 | Paclitaxel | <10% in 30 days | 0.23–0.39 [94] | |

| 2nd | Xience V | Abbott (Chicago, IL, USA) | CoCr | 81 | Durable (Fluoropolymer) | 7.6 | Everolimus | Full release in 90 days | 0.12–0.17 [95] |

| Resolute | Medtronic (Galway, Ireland) | CoCr | 91 | Durable/ Biodegradable (BioLinx) | 4.1 | Zotarolimus | Gradual release in 6 months | Mean 0.12 [96] | |

| 3rd | Synergy | Boston Scientific | PtCr | 74 | Biodegradable (PLGA) | 4 | Everolimus | Full release in 90 days | Mean 0.10 [97] |

| Orsiro | Biotronik (Berlin, Germany) | CoCr | 60 | Biodegradable (BIOlute) | 7.5 | Sirolimus | 50% in 30 days | Median 0.06 [96] | |

| 4th | Absorb | Abbott | PLLA | 130–150 | Fully bioresorbable (PDLLA) | / | Everolimus | 80% in 30 days | Mean 0.37 [98] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, Z.; Skarbek, C.; Li, Y.; Touma, J.; Desgranges, P.; Gallet, R.; Sénémaud, J. Evolution of Coronary Stents: From Birth to Future Trends. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010047

Huang Z, Skarbek C, Li Y, Touma J, Desgranges P, Gallet R, Sénémaud J. Evolution of Coronary Stents: From Birth to Future Trends. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Zhuo, Charles Skarbek, Yulin Li, Joseph Touma, Pascal Desgranges, Romain Gallet, and Jean Sénémaud. 2026. "Evolution of Coronary Stents: From Birth to Future Trends" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010047

APA StyleHuang, Z., Skarbek, C., Li, Y., Touma, J., Desgranges, P., Gallet, R., & Sénémaud, J. (2026). Evolution of Coronary Stents: From Birth to Future Trends. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010047