The Effect of Cognitive Training After Heart Valve Surgery: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

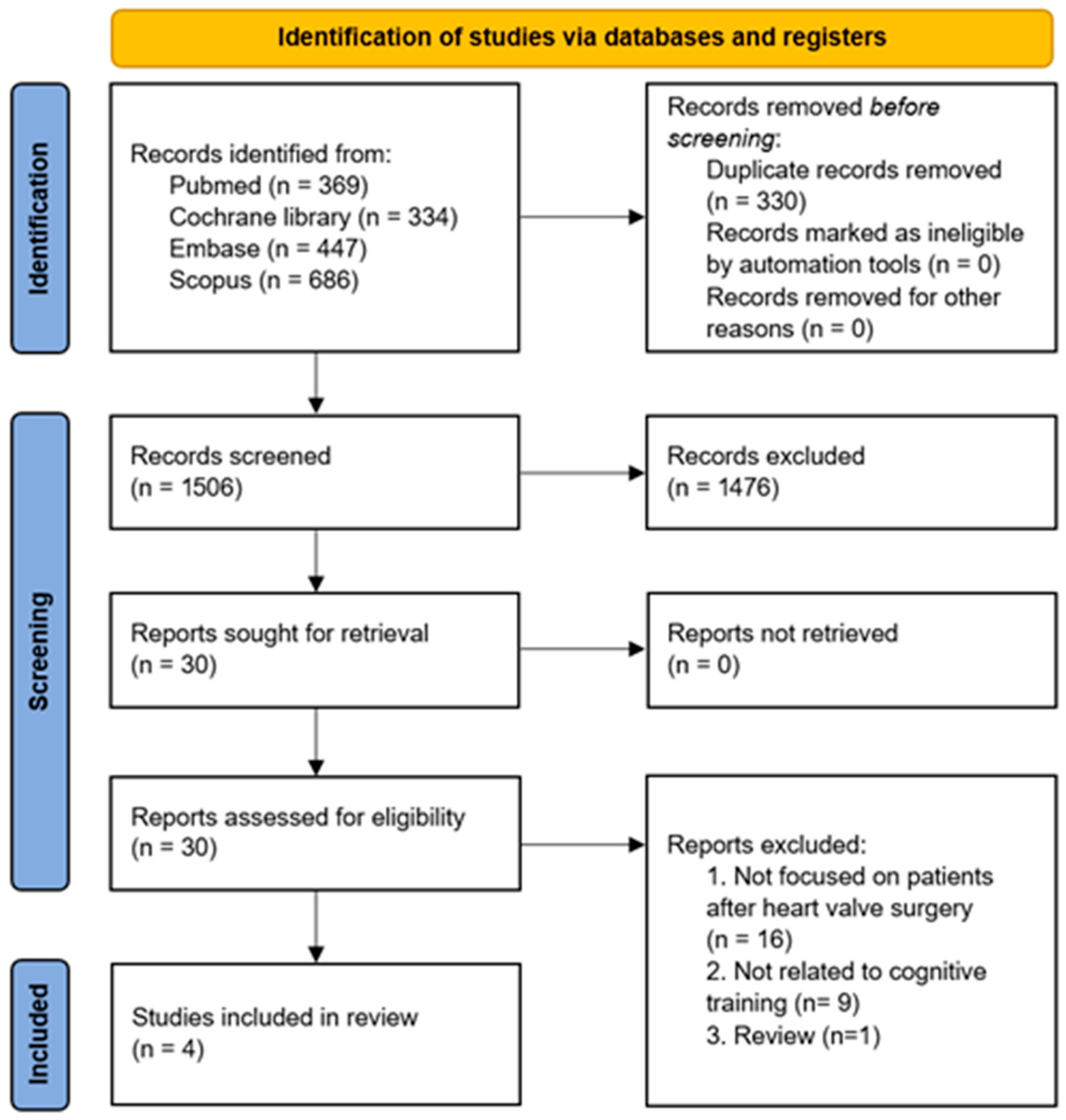

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

Review Registration

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

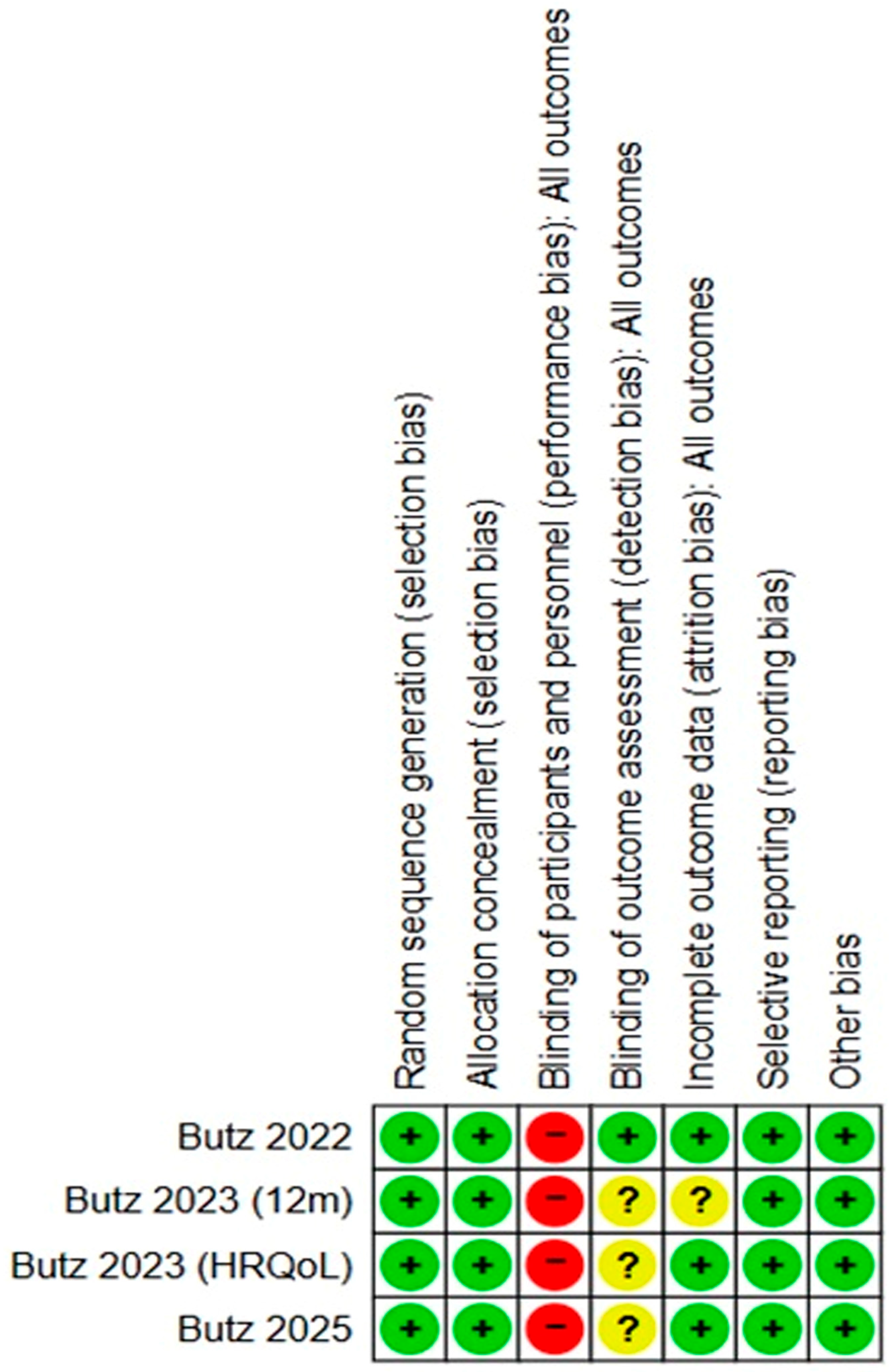

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| POCD | Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction |

| POCI | Postoperative Cognitive Improvement |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| SF-36 | Short Form 36 Health Survey |

| CFQ | Cognitive Failures Questionnaire |

| WML | White Matter Lesions |

| SCI | Subclinical Cerebral Ischemia |

| AVR | Aortic Valve Replacement |

| TAVR | Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement |

| MVR | Mitral Valve Replacement |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Cicekcioglu, F.; Ozen, A.; Tuluce, H.; Tutun, U.; Parlar, A.I.; Kervan, U.; Karakas, S.; Katircioglu, S.F. Neurocognitive functions after beating heart mitral valve replacement without cross-clamping the aorta. J. Card. Surg. 2008, 23, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, D.; Psaltis, P.J.; Ross, T.J.; Davis, D.; Smith, A.E.; Boord, M.S.; Keage, H.A. Cognitive outcomes following coronary artery bypass grafting: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 91,829 patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 289, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakin, R.; Zimpfer, D.; Sodeck, G.H.; Rajek, A.; Mora, B.; Dumfarth, J.; Grimm, M.; Czerny, M. Influence of temperature management on neurocognitive function in biological aortic valve replacement. A prospective randomized trial. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2012, 53, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, M.A.; Vachon, J.; Yuh, D.; Lee, H.B. Cognitive outcomes after heart valve surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 2327–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Minhas, J.S.; Chung, E.M. Risk factors associated with cognitive decline after cardiac surgery: A systematic review. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2015, 2015, 370612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Harten, A.E.; Scheeren, T.W.; Absalom, A.R. A review of postoperative cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation associated with cardiac surgery and anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2012, 67, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Clare, L.; Altgassen, A.M.; Cameron, M.H.; Zehnder, F. Cognition-based interventions for healthy older people and people with mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 1, Cd006220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.E.; Loughrey, D.; Lawlor, B.A.; Robertson, I.H.; Walsh, C.; Brennan, S. The impact of cognitive training and mental stimulation on cognitive and everyday functioning of healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2014, 15, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, C.M.; Chen, S.M.; Tian, F.M.; Huang, P.M.; Chen, Y.M. Effects of cognitive training on cognitive function in patients after cardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2024, 103, e40324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, X.; Mao, W.; Li, L. Preoperative cognitive training improves postoperative cognitive function: A meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1293153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, M.; Gerriets, T.; Sammer, G.; El-Shazly, J.; Tschernatsch, M.; Huttner, H.B.; Braun, T.; Boening, A.; Mengden, T.; Choi, Y.-H.; et al. Effects of postoperative cognitive training on neurocognitive decline after heart surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 62, ezac251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, M.; Gerriets, T.; Sammer, G.; El-Shazly, J.; Tschernatsch, M.; Schramm, P.; Doeppner, T.R.; Braun, T.; Boening, A.; Mengden, T.; et al. The impact of postoperative cognitive training on health-related quality of life and cognitive failures in daily living after heart valve surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, M.; Gerriets, T.; Sammer, G.; El-Shazly, J.; Tschernatsch, M.; Braun, T.; Meyer, R.; Schramm, P.; Doeppner, T.R.; Böning, A.; et al. Twelve-month follow-up effects of cognitive training after heart valve surgery on cognitive functions and health-related quality of life: A randomised clinical trial. Open Heart 2023, 10, e002411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, M.; Gerriets, T.; Sammer, G.; El-Shazly, J.; Braun, T.; Sünner, L.; Meyer, R.; Tschernatsch, M.; Schramm, P.; Gerner, S.T.; et al. The impact of white matter lesions and subclinical cerebral ischemia on postoperative cognitive training outcomes after heart valve surgery: A randomized clinical trial. J. Neurol. Sci. 2025, 469, 123370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadoi, Y.; Kawauchi, C.; Ide, M.; Kuroda, M.; Takahashi, K.; Saito, S.; Fujita, N.; Mizutani, A. Preoperative depression is a risk factor for postoperative short-term and long-term cognitive dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Anesth. 2011, 25, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekker, A.; Lee, C.; de Santi, S.; Pirraglia, E.; Zaslavsky, A.; Farber, S.; Haile, M.; de Leon, M.J. Does mild cognitive impairment increase the risk of developing postoperative cognitive dysfunction? Am. J. Surg. 2010, 199, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, M.; Terrando, N.; Smith, S.K.; Browndyke, J.N.; Newman, M.F.; Mathew, J.P. Neurocognitive function after cardiac surgery: From phenotypes to mechanisms. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 829–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranucci, L.; Brischigiaro, L.; Mazzotta, V.; Anguissola, M.; Menicanti, L.; Bedogni, F.; Ranucci, M. Neurocognitive function in procedures correcting severe aortic valve stenosis: Patterns and determinants. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1372792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozolic, J.L.; Hayasaka, S.; Laurienti, P.J. A cognitive training intervention increases resting cerebral blood flow in healthy older adults. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, B.M.; Chen, C. Circuitry underlying experience-dependent plasticity in the mouse visual system. Neuron 2020, 106, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appelbaum, L.G.; Shenasa, M.A.; Stolz, L.; Daskalakis, Z. Synaptic plasticity and mental health: Methods, challenges and opportunities. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zotey, V.; Andhale, A.; Shegekar, T.; Juganavar, A. Adaptive neuroplasticity in brain injury recovery: Strategies and insights. Cureus 2023, 15, e45873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, D.; Hegde, S.; Thaut, M. Neural plasticity: The substratum of music-based interventions in neurorehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation 2021, 48, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutuli, D.; Landolfo, E.; Petrosini, L.; Gelfo, F. Environmental enrichment effects on the brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in healthy condition, Alzheimer’s disease, and other neurodegenerative disorders. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 85, 975–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.C.; Bischof, G.N. The aging mind: Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive training. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 15, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Fang, P.; Shang, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhou, J.; Yang, C.; Zhu, W.; Hao, X.; Ding, J.; et al. Cognitive training for reduction of delirium in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e247361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainz, E.; Juilfs, N.; Harler, U.; Kahl, U.; Mewes, C.; Zöllner, C.; Fischer, M. The impact of cognitive reserve on delayed neurocognitive recovery after major non-cardiac surgery: An exploratory substudy. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1267998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Author | Year | Study Design | Number of Participants (Treatment vs. Control) | Type of Intervention | Control Group | Treatment Duration | Follow-Up Period | Evaluation Tool | Effect Size | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Butz et al. [12] | 2022 | RCT | 60 (31 vs. 29) | Paper-and-pencil cognitive training | No cognitive training (standard cardiac rehabilitation) | 36 min/day, 6 days/week for 3 weeks | 3 months | Neuropsychological test battery (visual/verbal memory, executive function, attention) | POCD incidence: OR = 4.29 (discharge); OR = 6.46 (3 months) | The cognitive training group showed significantly lower rates of POCD and higher rates of POCI at 3 months compared with the control group |

| 2 | Butz et al. [13] | 2023 | RCT | 60 (31 vs. 29) | Paper-and-pencil cognitive training | No cognitive training (standard cardiac rehabilitation) | Approx. 15 days | 3 months | SF-36, CFQ | SF-36 mental component summary: η2 = 0.102 | The cognitive training group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in global HRQoL, overall SF-36 scores, and perceived health change, compared with the control group |

| 3 | Butz et al. [14] | 2023 | RCT | 58 (30 vs. 28) | Paper-and-pencil cognitive training | No cognitive training (standard cardiac rehabilitation) | 36 min/day, 6 days/week for 3 weeks | 12 months | Neuropsychological tests, SF-36, CFQ | POCD incidence: OR = 2.43 | Significantly greater improvements in HRQoL were observed in the cognitive training group compared with the control group |

| 4 | Butz et al. [15] | 2025 | RCT | 39 (18 vs. 21) | Paper-and-pencil cognitive training | Standard cardiac rehabilitation only | 36 min/day, 6 days/week for 3 weeks | 3 and 12 months | Neuropsychological tests, SF-36, HADS, MRI for WML/SCI | SF-36 mental component summary: η2 = 0.185 (3 months) | The cognitive training group showed greater improvements in cognition and HRQoL at 3 months than the control group, independent of the presence of WML and SCI |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yi, Y.G.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, D.; Yang, S.; Chang, M.C. The Effect of Cognitive Training After Heart Valve Surgery: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010370

Yi YG, Kim Y, Kwon D, Yang S, Chang MC. The Effect of Cognitive Training After Heart Valve Surgery: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):370. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010370

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, You Gyoung, Younji Kim, Daegil Kwon, Seoyon Yang, and Min Cheol Chang. 2026. "The Effect of Cognitive Training After Heart Valve Surgery: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010370

APA StyleYi, Y. G., Kim, Y., Kwon, D., Yang, S., & Chang, M. C. (2026). The Effect of Cognitive Training After Heart Valve Surgery: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010370