Effectiveness of a Modified Transsellar Approach with Planum Sphenoidale Removal for Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors with Anterosuperior Extension

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

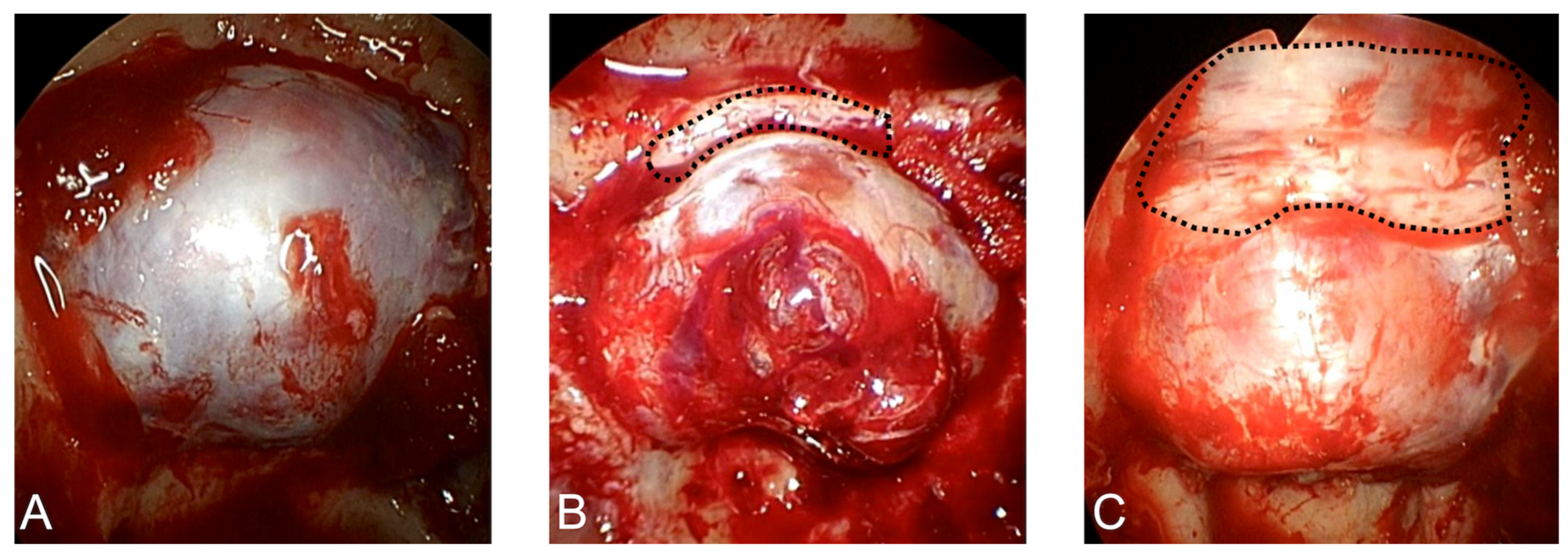

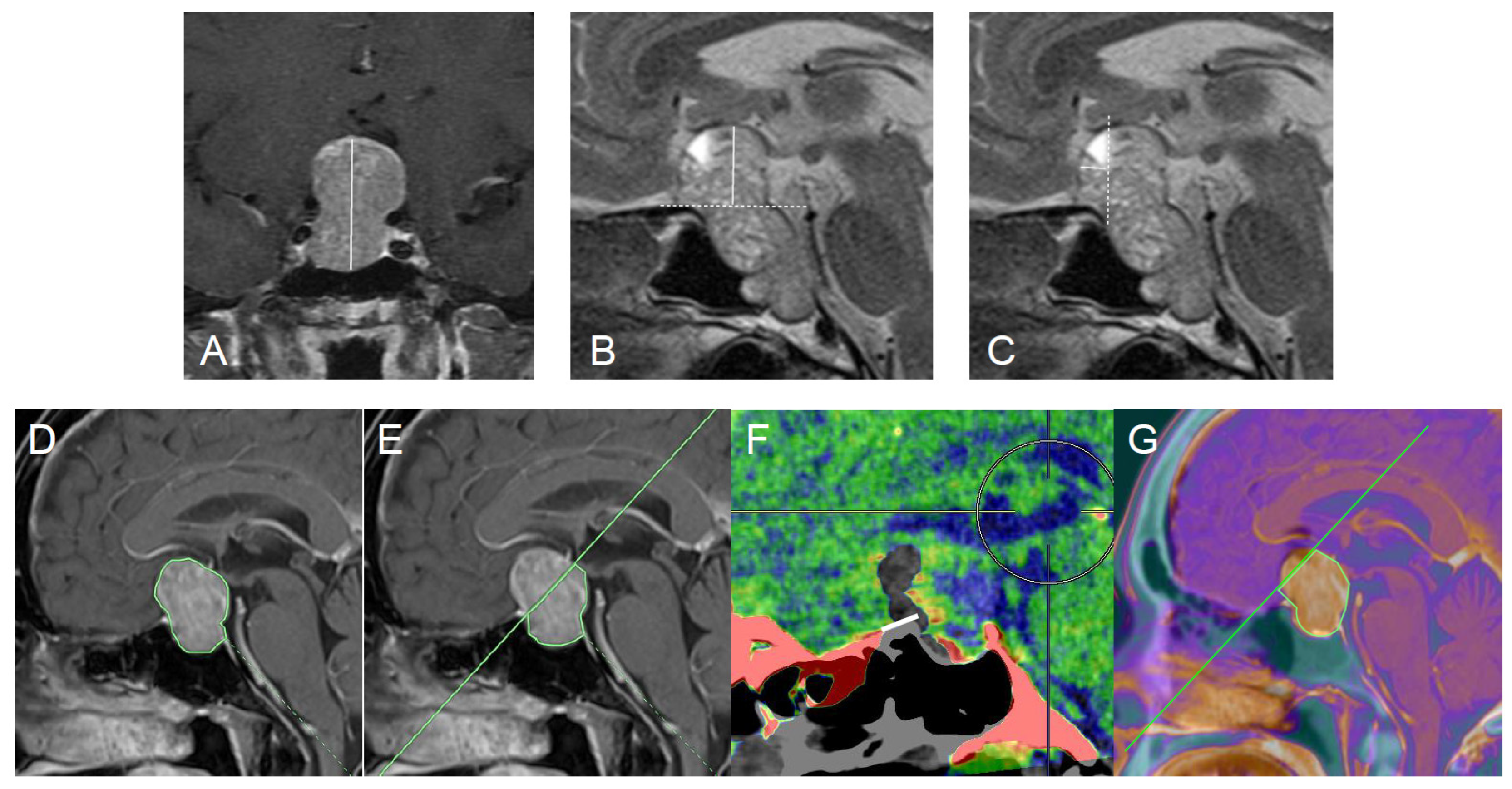

2.2. Surgical Procedure

2.3. Radiological Assessments

2.4. Surgical Outcome

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. TSA for PitNETs with Anterosuperior Extension

4.2. Advantages of mTSA for PitNETs with Anterosuperior Extension

4.3. Safety of mTSA

4.4. Limitation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| ETS | Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery |

| EETS | Extended endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery |

| GTR | gross total resection |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| mTSA | Modified transsellar approach |

| PitNET | Pituitary neuroendocrine tumor |

| PS | Planum sphenoidale |

| TS | Tuberculum sellae |

| TSA | Transsellar approach |

References

- Sivakumar, W.; Chamoun, R.; Nguyen, V.; Couldwell, W.T. Incidental pituitary adenomas. Neurosurg. Focus 2011, 31, E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molitch, M.E. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pituitary Adenomas: A Review. JAMA 2017, 317, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sun, C.; Tian, W.; Bao, Z.; Gao, H.; Wang, J.; Lu, X.; Wang, Q. Endoscopic endonasal approaches for resection of suprasellar pituitary neuroendocrine tumors: A novel classification based on the optic chiasm and operative nuances. BMC Surg. 2025, 25, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Malek, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Ramak Hashemi, S.M.; Khamseh, M.E.; Zare Mehrjardi, A.; Emami, Z.; Ebrahim Valojerdi, A. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic versus microscopic trans-sphenoidal surgery for large pituitary adenoma. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 32, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, S.T.; Morshed, R.A.; Lucas, C.G.; Aghi, M.K.; Theodosopoulos, P.V.; Berger, M.S.; de Divitiis, O.; Solari, D.; Cappabianca, P.; Cavallo, L.M.; et al. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: Grading scale to assess surgical outcomes using the transcranial versus transsphenoidal approach. Neurosurg. Focus 2018, 44, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Divitiis, E.; Cappabianca, P.; Cavallo, L.M.; Esposito, F.; de Divitiis, O.; Messina, A. Extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for extrasellar craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery 2007, 61, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Deng, K.; Lu, L.; Yao, Y. Suprasellar pituitary adenomas: A 10-year experience in a single tertiary medical center and a literature review. Pituitary 2020, 23, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Shen, H.; Peng, G.; Zhou, J.; Xu, D.; Che, Y.; Mo, J. The Role of Comprehensive Structural Preservation Strategy in Skull Base Reconstruction Following Endoscopic Endonasal Surgery for Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. World Neurosurg. 2025, 200, 124171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solari, D.; d’Avella, E.; Barkhoudarian, G.; Zoli, M.; Cheok, S.; Bove, I.; Gianluca, L.; Zada, G.; Mazzatenta, D.; Kelly, D.F.; et al. Indications and outcomes of the extended endoscopic endonasal approach for the removal of “unconventional” suprasellar pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. J. Neurosurg. 2025, 143, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Sharma, B.S. Giant pituitary adenomas--an enigma revisited. Microsurgical treatment strategies and outcome in a series of 250 patients. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2010, 24, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micko, A.S.G.; Keritam, O.; Marik, W.; Strickland, B.A.; Briggs, R.G.; Shahrestani, S.; Cardinal, T.; Knosp, E.; Zada, G.; Wolfsberger, S. Dumbbell-shaped pituitary adenomas: Prognostic factors for prediction of tumor nondescent of the supradiaphragmal component from a multicenter series. J. Neurosurg. 2021, 137, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarenko, S.; Alzahrani, I.; Karsy, M.; Deopujari, C.; Couldwell, W.T. Outcomes and surgical nuances in management of giant pituitary adenomas: A review of 108 cases in the endoscopic era. J. Neurosurg. 2022, 137, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Cao, J.; Jie, Y.; Wang, L. Transsphenoidal Surgery of Giant Pituitary Adenoma: Results and Experience of 239 Cases in A Single Center. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 879702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, Y.; Takeuchi, K.; Iwami, K.; Okumura, E.; Sato, Y.; Hirose, T.; Saito, R. Surgical Strategies for Giant Pituitary Adenomas to Minimize Postoperative Hematoma Formation. Neurol. Med.-Chir. 2025, 65, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Corrales, E.; Acitores Cancela, A.; Baonza, G.; Madrid Egusquiza, I.; Rodríguez Berrocal, V.; Araujo-Castro, M. Clinical presentation and surgical outcomes of very large and giant pituitary adenomas: 80 cases in a cohort study of 306 patients with pituitary adenomas. Acta Neurochir. 2024, 166, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, B.K.; Binu, A.; Stanley, A.; Shah, S.K.; Darshan, H.R.; George, T.; Easwer, H.V.; Nair, P. Large pituitary adenoma: Strategies to maximize volumetric resection using endoscopic endonasal approaches and an analysis of factors limiting resection. World Neurosurg. 2022, 167, e694–e704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalif, E.J.; Couldwell, W.T.; Aghi, M.K. Effect of facility volume on giant pituitary adenoma neurosurgical outcomes. J. Neurosurg. 2022, 137, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.S.; Agazzi, S.; van Loveren, H.R. Transcranial surgery for pituitary adenomas. Neurosurgery 2005, 57, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emengen, A.; Yilmaz, E.; Gokbel, A.; Uzuner, A.; Balci, S.; Ozkan, S.; Tavukcu, E.; Ergen, A.; Caklili, M.; Cabuk, B.; et al. Refining Endoscopic and Combined Surgical Strategies for Giant Pituitary Adenomas: A Tertiary-Center Evaluation of 49 Cases over the Past Year. Cancers 2025, 17, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyooka, T.; Osada, H.; Otani, N.; Tomiyama, A.; Takeuchi, S. Simultaneous combined keyhole mini-transcranial approach and endoscopic transsphenoidal approach to remove multi-lobulated pituitary neuroendocrine tumor with suprasellar extension. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2024, 245, 108512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, P.; Rodríguez Berrocal, V.; Díez, J.J. Giant pituitary adenoma: Histological types, clinical features and therapeutic approaches. Endocrine 2018, 61, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathalla, H.; Di leva, A.; Lee, J.; Anderson, J.; Jing, R.; Solarski, M.; Cusimano, M.D. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks in extended endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery: Covering all the angles. Neurosurg. Rev. 2017, 40, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chen, P.; Lv, S.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, H.; Huang, R.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, Z. Evaluation of the gross total resection rate of suprasellar pituitary macroadenomas with and without the removal of the tuberculum sellae bone. World Neurosurg. 2021, 156, e291–e299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.S.; Na, H.S.; Kim, S.D.; Yi, K.I.; Mun, S.J.; Cho, K.S. Septal cartilage traction suture technique for correction of caudal septal deviation. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, E758–E763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, R.; Tosaka, M.; Miyagishima, T.; Osawa, T.; Horiguchi, K.; Honda, F.; Yoshimoto, Y. Sagittal bending of the optic nerve at the entrance from the intracranial to the optic canal and ipsilateral visual acuity in patients with sellar and suprasellar lesions. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 134, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, R.; Tosaka, M.; Shinohara, Y.; Todokoro, D.; Mukada, N.; Miyagishima, T.; Akiyama, H.; Yoshimoto, Y. Analysis of visual field disturbance in patients with sellar and suprasellar lesions: Relationship with magnetic resonance imaging findings and sagittal bending of the optic nerve. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2022, 122, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosaka, M.; Prevedello, D.M.; Yamaguchi, R.; Fukuhara, N.; Miyagishima, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Aihara, M.; Shimizu, T.; Yoshimoto, Y. Single-layer fascia patchwork closure for the extended endoscopic transsphenoidal transtuberculum transplanum approach: Deep suturing technique and preliminary results. World Neurosurg. 2021, 155, e271–e284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Hong, Y.K.; Jeun, S.S.; Park, J.S.; Lim, D.J.; Kim, S.W.; Cho, J.H.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, Y.G.; Kim, S.W. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach from the surgeon point of view. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2017, 28, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehdashti, A.R.; Ganna, A.; Witterick, I.; Gentili, F. Expanded endoscopic endonasal approach for anterior cranial base and suprasellar lesions: Indications and limitations. Neurosurgery 2009, 64, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Notaris, M.; Solari, D.; Cavallo, L.M.; D’Enza, A.I.; Ensenat, J. The “suprasellar notch,” or the tuberculum sellae as seen from below: Definition, features, and clinical implications from an endoscopic endonasal perspective: Laboratory investigation. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 116, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, A.; Kirkman, M.A.; Choi, D. Endoscopic endonasal anterior skull base surgery: A systematic review of complications during the past 65 years. World Neurosurg. 2016, 95, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes Medina, B.; Linsler, S.; Saffour, S.; Sitoci-Ficici, K.H.; Oertel, J. Dural repair after intraoperative CSF leakage in endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery without pedicled nasoseptal flap: Is it a safe surgical technique? Neurosurg. Rev. 2025, 48, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, R.; Tosaka, M.; Mukada, N.; Tsuneoka, H.; Shimauchi-Otaki, H.; Miyagishima, T.; Honda, F.; Yoshimoto, Y. Postoperative serum c-reactive protein and cerebrospinal fluid leakage after endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 2022, 84, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tumors Treated via TSA (n = 77) | Tumors Treated by mTSA (n = 27) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60 (37–83) | 65 (44–86) | 0.35 |

| Female sex, no. (%) | 32 (41%) | 8 (27%) | 0.36 |

| Preoperative tumor factor | |||

| Tumor height, mm | 25 (18–32) | 32 (23–41) | <0.001 |

| Tumor top-anterior skull base distance, mm | 8.8 (2.0–15.6) | 15.1 (5.8–24.4) | <0.001 |

| Tumor anterior tip-tuberculum sellae distance, mm | 0 (0) | 4.6 (0–9.8) | |

| Postoperative factor | |||

| Planum sphenoidale removal distance, mm | 4.4 (0.1–8.7) | ||

| Tumor area measurement | |||

| Total tumor area, mm2 | 365 (118–612) | 615 (353–877) | <0.001 |

| Via TSA | |||

| Accessible tumor area, mm2 | 295 (122–468) | ||

| Ratio of accessible area to whole tumor area via TSA (%) | 83 (61–100) | ||

| Via mTSA | |||

| Hypothetical accessible tumor area via TSA, mm2, % | 381 (99–663), 70% | ||

| Accessible tumor area via mTSA, mm2, % | 520 (264–776), 88% | <0.001 | |

| Ratio of accessible area to whole tumor area via mTSA (%) | 88 (70–100) |

| Tumors Treated via TSA (n = 77) | Tumors Treated by mTSA (n = 27) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebrospinal fluid leakage, no. (%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (4%) |

| Meningitis, no. (%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (4%) |

| Ocular movement disturbance, no. (%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Visual worsening, no. (%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Symptomatic hemorrhage, no. (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Anosmia, no. (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yamaguchi, R.; Tosaka, M.; Mukada, N.; Aihara, M.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Oya, S. Effectiveness of a Modified Transsellar Approach with Planum Sphenoidale Removal for Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors with Anterosuperior Extension. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010367

Yamaguchi R, Tosaka M, Mukada N, Aihara M, Yoshimoto Y, Oya S. Effectiveness of a Modified Transsellar Approach with Planum Sphenoidale Removal for Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors with Anterosuperior Extension. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010367

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamaguchi, Rei, Masahiko Tosaka, Naoto Mukada, Masanori Aihara, Yuhei Yoshimoto, and Soichi Oya. 2026. "Effectiveness of a Modified Transsellar Approach with Planum Sphenoidale Removal for Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors with Anterosuperior Extension" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010367

APA StyleYamaguchi, R., Tosaka, M., Mukada, N., Aihara, M., Yoshimoto, Y., & Oya, S. (2026). Effectiveness of a Modified Transsellar Approach with Planum Sphenoidale Removal for Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors with Anterosuperior Extension. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010367