Five-Year Follow-Up of Photobiomodulation in Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Series Exploring Clinical Stability and Microbiome Modulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Sample Collection, DNA Extraction, and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Microbiome Diversity

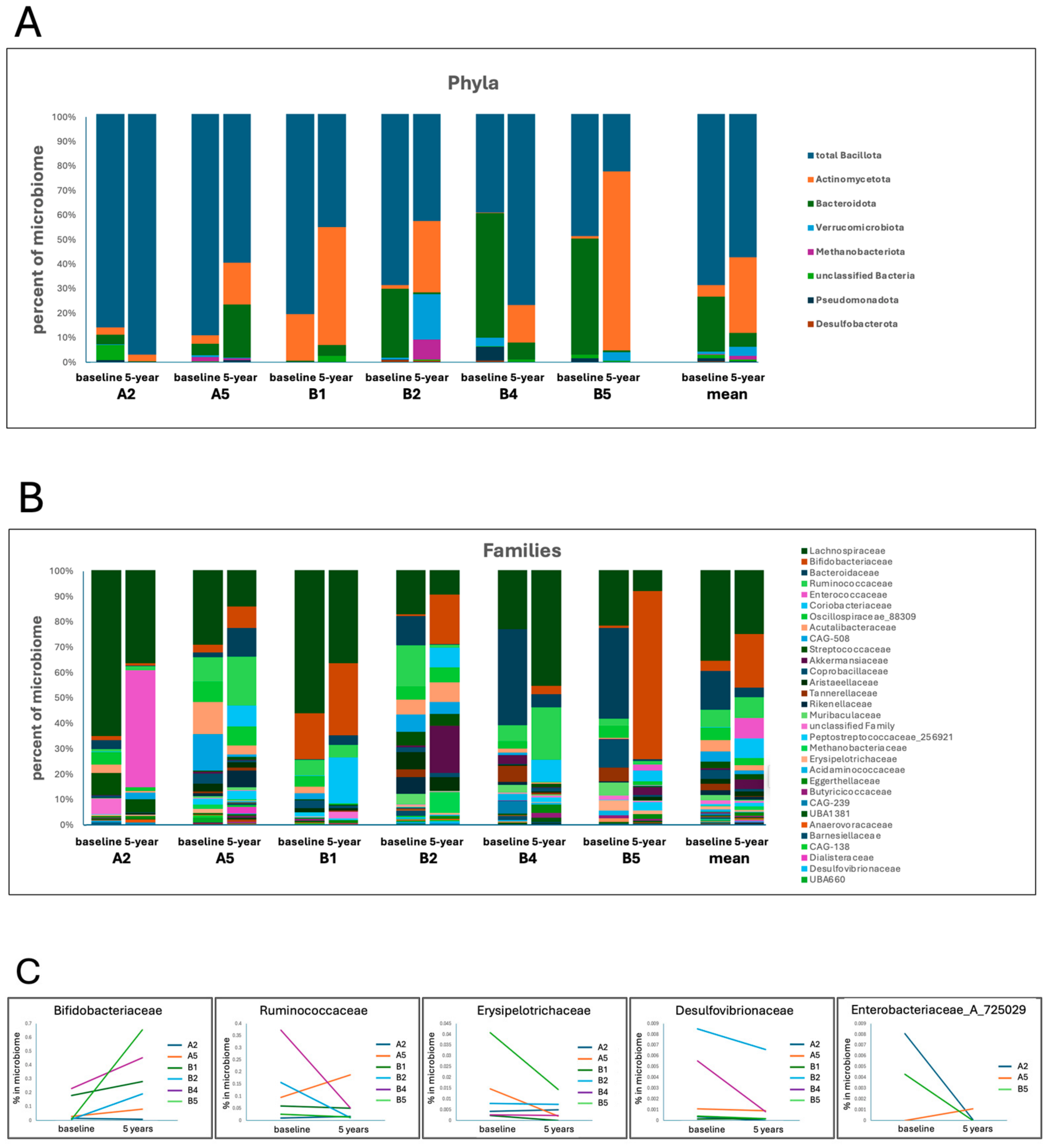

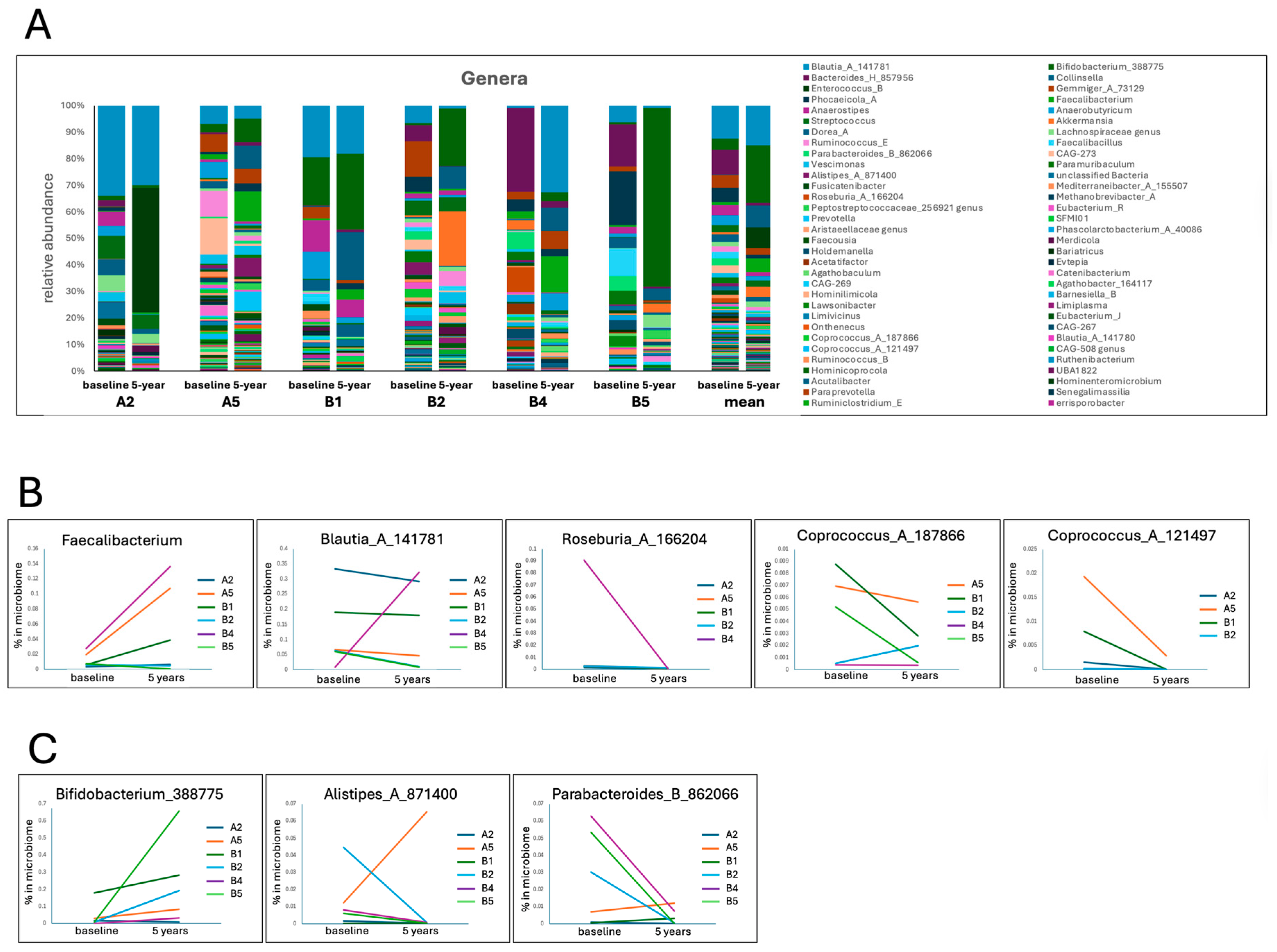

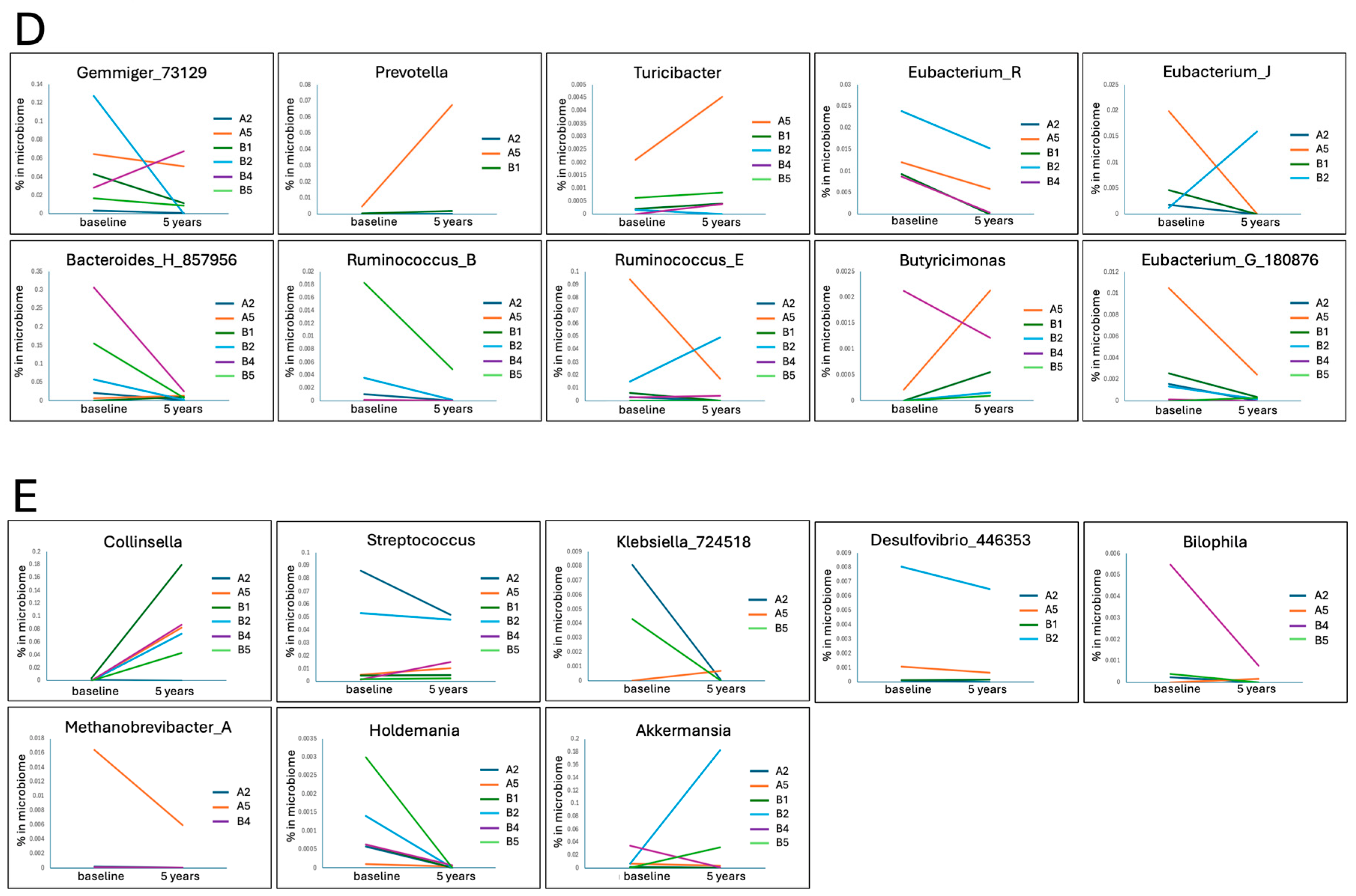

3.2. Taxonomic Changes

4. Discussion

4.1. Longterm Clinical Stability

4.2. Microbiome Shifts

4.3. Mechanistic Links Between PBM and the Microbiome

4.4. Comparison with Other Microbiome-Targeted Interventions

5. Limitations

Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, H.C.; Ulane, C.M.; Burke, R.E. Clinical progression in Parkinson disease and the neurobiology of axons. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 67, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghammer, P.; Van Den Berge, N. Brain-First versus Gut-First Parkinson’s Disease: A Hypothesis. J. Park. Dis. 2019, 9, S281–S295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmqvist, S.; Chutna, O.; Bousset, L.; Aldrin-Kirk, P.; Li, W.; Björklund, T.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Roybon, L.; Melki, R.; Li, J.-Y. Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 2014, 128, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, M.X.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.-Y. α-Synuclein pathology in Parkinson’s disease and related α-synucleinopathies. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 709, 134316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, C.; Yaghi, N.; El Hayeck, R.; Heraoui, G.N.; Fakhoury-Sayegh, N. Nutritional risk factors, microbiota and Parkinson’s disease: What is the current evidence? Nutrients 2019, 11, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, J.; Gage, H.; Kimber, A.; Storey, L.; Trend, P. Excess burden of constipation in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 1270–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, K.; Krogh, K.; Østergaard, K.; Borghammer, P. Constipation in Parkinson’s disease: Subjective symptoms, objective markers, and new perspectives. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, N.H.; Rashwan, H.H.; El-Hadidi, M.; Ramadan, R.; Mysara, M. Proinflammatory and GABA eating bacteria in Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome from a meta-analysis perspective. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Savva, G.M.; Bedarf, J.R.; Charles, I.G.; Hildebrand, F.; Narbad, A. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. npj Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.B.; Malireddi, A.; Abera, M.; Noor, K.; Ansar, M.; Boddeti, S.; Nath, T.S. Gut Microbiome and Its Role in Parkinson’s Disease. Cureus 2024, 16, e73150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; You, L.; Lei, H.; Li, X. Association between increased and decreased gut microbiota abundance and Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and subgroup meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2024, 191, 112444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.G.; Kang, W.; Shin, I.-J.; Chalita, M.; Oh, H.-S.; Hyun, D.-W.; Kim, H.; Chun, J.; An, Y.-S.; Lee, E.J.; et al. Difference in gut microbial dysbiotic patterns between body-first and brain-first Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 201, 106655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, D.; Postuma, R.B.; Adler, C.H.; Bloem, B.R.; Chan, P.; Dubois, B.; Gasser, T.; Goetz, C.G.; Halliday, G.; Joseph, L.; et al. MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelli, M.; Franza, L.; Pignataro, G.; Ojetti, V.; Covino, M.; Piccioni, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Franceschi, F. Interaction between lipopolysaccharide and gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, F.; Hertel, J.; Sandt, E.; Thinnes, C.C.; Neuberger-Castillo, L.; Pavelka, L.; Betsou, F.; Krüger, R.; Thiele, I.; Consortium, N.-P. Parkinson’s disease-associated alterations of the gut microbiome predict disease-relevant changes in metabolic functions. BMC Biol. 2020, 18, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Chiang, H.-L.; Liou, J.-M.; Chang, C.-M.; Lu, T.-P.; Chuang, E.Y.; Tai, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.; Lin, H.-Y.; et al. Altered gut microbiota and inflammatory cytokine responses in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe-Roach, A.; Finlay, B.B. The role of the gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease. Future Neurol. 2025, 20, 2494981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. Mechanisms and Mitochondrial Redox Signaling in Photobiomodulation. Photochem. Photobiol. 2018, 94, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghfour, J.; Mineroff, J.; Ozog, D.M.; Jagdeo, J.; Lim, H.W.; Kohli, I.; Anderson, R.; Kelly, K.M.; Mamalis, A.; Munavalli, G.; et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2025, 93, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Massri, N.; Johnstone, D.M.; Peoples, C.L.; Moro, C.; Reinhart, F.; Torres, N.; Stone, J.; Benabid, A.-L.; Mitrofanis, J. The effect of different doses of near infrared light on dopaminergic cell survival and gliosis in MPTP-treated mice. Int. J. Neurosci. 2016, 126, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, D.M.; el Massri, N.; Moro, C.; Spana, S.; Wang, X.S.; Torres, N.; Chabrol, C.; De Jaeger, X.; Reinhart, F.; Purushothuman, S.; et al. Indirect application of near infrared light induces neuroprotection in a mouse model of parkinsonism—An abscopal neuroprotective effect. Neuroscience 2014, 274, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltmarche, A.E.; Hares, O.; Bicknell, B.; Liebert, A.; Naeser, M.; Ramachandran, S.; Sykes, J.; Togeretz, K.; Namini, A.; Heller, G.Z.; et al. Effectiveness of Photobiomodulation to Treat Motor and Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomised Clinical Trial with Extended Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebert, A.; Bicknell, B.; Laakso, E.-L.; Tilley, S.; Heller, G.; Kiat, H.; Herkes, G. Improvements in clinical signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease using photobiomodulation: A five-year follow-up. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herkes, G.; McGee, C.; Liebert, A.; Bicknell, B.; Isaac, A.; Kiat, H.; McLachlan, C. A novel transcranial photobiomodulation device to address motor signs of Parkinson’s disease: A parallel randomised feasibility study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 66, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebert, A.; Bicknell, B.; Laakso, E.L.; Heller, G.; Jalilitabaei, P.; Tilley, S.; Mitrofanis, J.; Kiat, H. Improvements in clinical signs of Parkinson’s disease using photobiomodulation: A prospective proof-of-concept study. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, B.; Liebert, A.; Johnstone, D.; Kiat, H. Photobiomodulation of the microbiome: Implications for metabolic and inflammatory diseases. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, B.; Liebert, A.; McLachlan, C.S.; Kiat, H. Microbiome Changes in Humans with Parkinson’s Disease after Photobiomodulation Therapy: A Retrospective Study. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, B.; Saltmarche, A.; Hares, O.; Herkes, G.; Liebert, A. Parkinson’s disease and the Interaction of Photobiomodulation, the Microbiome, and Antibiotics: A Case Series. Med. Res. Arch. 2024, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.; Jiang, Y.; Balaban, M.; Cantrell, K.; Zhu, Q.; Gonzalez, A.; Morton, J.T.; Nicolaou, G.; Parks, D.H.; Karst, S.M.; et al. Greengenes2 unifies microbial data in a single reference tree. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Pirrung, M.; Gonzalez, A.; Knight, R. EMPeror: A tool for visualizing high-throughput microbial community data. Gigascience 2013, 2, 2047-2217X-2042-2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, S.; Van Treuren, W.; White, R.A.; Eggesbø, M.; Knight, R.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of composition of microbiomes: A novel method for studying microbial composition. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 27663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aho, V.T.E.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Voutilainen, S.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Auvinen, P.; Scheperjans, F. Gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease: Temporal stability and relations to disease progression. eBioMedicine 2019, 44, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Yue, L.; Fang, X.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; Sun, X.; Jia, X.; Yang, J.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Altered gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease patients/healthy spouses and its association with clinical features. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 81, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirstea, M.S.; Yu, A.C.; Golz, E.; Sundvick, K.; Kliger, D.; Radisavljevic, N.; Foulger, L.H.; Mackenzie, M.; Huan, T.; Finlay, B.B.; et al. Microbiota Composition and Metabolism Are Associated With Gut Function in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, S.; Gorthi, S.P.; Prabhu, A.N.; Das, B.; Mutreja, A.; Vasudevan, K.; Shetty, V.; Ramamurthy, T.; Ballal, M. Dysbiosis of the Beneficial Gut Bacteria in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease from India. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2023, 26, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, T.S.; Chong, C.W.; Lim, S.-Y.; Bowman, J.; Cirstea, M.; Lin, C.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Appel-Cresswell, S.; Finlay, B.B.; Tan, A.H. Gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease: New insights from meta-analysis. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 94, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barichella, M.; Severgnini, M.; Cilia, R.; Cassani, E.; Bolliri, C.; Caronni, S.; Ferri, V.; Cancello, R.; Ceccarani, C.; Faierman, S.; et al. Unraveling gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Sandhu, K.; Peterson, V.; Dinan, T.G. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Burns, E.M.; Debelius, J.W.; Morton, J.T.; Wissemann, W.T.; Lewis, M.R.; Wallen, Z.D.; Peddada, S.D.; Factor, S.A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C.P.; et al. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Velazquez, D.; Kidwai, S.; Liu, T.C.; El-Yacoubi, M.A.; Garssen, J.; Tonda, A.; Lopez-Rincon, A. Understanding Parkinson’s: The microbiome and machine learning approach. Maturitas 2025, 193, 108185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Yang, F.; Cao, J.; Ding, W.; Yan, S.; Shi, W.; Wen, S.; Yao, L. Alterations of gut microbiota and metabolome with Parkinson’s disease. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 160, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metwaly, A.; Reitmeier, S.; Haller, D. Microbiome risk profiles as biomarkers for inflammatory and metabolic disorders. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzum, N.D.; Szymlek-Gay, E.A.; Loke, S.; Dawson, S.L.; Teo, W.-P.; Hendy, A.M.; Loughman, A.; Macpherson, H. Differences in the gut microbiome across typical ageing and in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropharmacology 2023, 235, 109566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, M.; AbuRaya, S.; Ahmed, S.M.; Ashmawy, G.; Ibrahim, A.; AbdelKhaliq, E. Study of the gut microbiome in Egyptian patients with Parkinson’s Disease. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhong, Y.; Sun, Y. Retrospective analysis of diet and gut microbiota diversity and clinical pharmacology outcomes in patients with Parkinsonism syndrome. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Onose, G.; Rotariu, M.; Poștaru, M.; Turnea, M.; Galaction, A.I. Role of Microbiota-Derived Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) in Modulating the Gut-Brain Axis: Implications for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullich, C.; Keshavarzian, A.; Garssen, J.; Kraneveld, A.; Perez-Pardo, P. Gut Vibes in Parkinson’s Disease: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2019, 6, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, H.; Hu, Y.; Lu, L.; Zheng, C.; Fan, Y.; Wu, B.; Zou, T.; Luo, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Gut bacterial profiles in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murros, K.E. Hydrogen Sulfide Produced by Gut Bacteria May Induce Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Wu, J.; Wu, L.; Sun, X.; Chen, C.; Huang, L. The utilization of N-acetylgalactosamine and its effect on the metabolism of amino acids in Erysipelotrichaceae strain. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, L.; He, P.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Deng, G.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Gut Microbiome and Lipid Metabolism in Mice Infected with Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Metabolites 2022, 12, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubomski, M.; Xu, X.; Holmes, A.J.; Muller, S.; Yang, J.Y.H.; Davis, R.L.; Sue, C.M. Nutritional Intake and Gut Microbiome Composition Predict Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 881872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aho, V.T.E.; Houser, M.C.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Chang, J.; Rudi, K.; Paulin, L.; Hertzberg, V.; Auvinen, P.; Tansey, M.G.; Scheperjans, F. Relationships of gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, inflammation, and the gut barrier in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiwaki, H.; Ito, M.; Hamaguchi, T.; Maeda, T.; Kashihara, K.; Tsuboi, Y.; Ueyama, J.; Yoshida, T.; Hanada, H.; Takeuchi, I.; et al. Short chain fatty acids-producing and mucin-degrading intestinal bacteria predict the progression of early Parkinson’s disease. npj Park. Dis. 2022, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, N.; Wilkinson, J.; Bjornevik, K.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; McIver, L.; Ascherio, A.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomics of the Gut Microbiome in Parkinson’s Disease: Prodromal Changes. Ann. Neurol. 2023, 94, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Huang, S.-Y.; Chen, S.-D.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Yu, J.-T. Investigating Casual Associations Among Gut Microbiota, Metabolites, and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 87, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Kang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Yang, H.; Fan, W. Gut Microbiota and Parkinson’s Disease: Implications for Faecal Microbiota Transplantation Therapy. ASN Neuro 2021, 13, 17590914211016217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lv, X.; Ye, T.; Zhao, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Xie, H.; Zhan, L.; Chen, L.; et al. Microbiota-microglia crosstalk between Blautia producta and neuroinflammation of Parkinson’s disease: A bench-to-bedside translational approach. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 117, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewaschuk, J.B.; Diaz, H.; Meddings, L.; Diederichs, B.; Dmytrash, A.; Backer, J.; Looijer-van Langen, M.; Madsen, K.L. Secreted bioactive factors from Bifidobacterium infantis enhance epithelial cell barrier function. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 295, G1025–G1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minato, T.; Maeda, T.; Fujisawa, Y.; Tsuji, H.; Nomoto, K.; Ohno, K.; Hirayama, M. Progression of Parkinson’s disease is associated with gut dysbiosis: Two-year follow-up study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, B.J.; Wearsch, P.A.; Veloo, A.C.M.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A. The Genus Alistipes: Gut Bacteria With Emerging Implications to Inflammation, Cancer, and Mental Health. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallen, Z.D.; Demirkan, A.; Twa, G.; Cohen, G.; Dean, M.N.; Standaert, D.G.; Sampson, T.R.; Payami, H. Metagenomics of Parkinson’s disease implicates the gut microbiome in multiple disease mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Chang, R.; Xu, M.; Zhou, G.; Meng, J.; Liu, D.; Mao, Z.; Yang, Y. Gut microbiota from patients with Parkinson’s disease causes motor deficits in honeybees. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1418857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.; Saltykova, I.; Zhukova, I.; Alifirova, V.; Zhukova, N.; Dorofeeva, Y.B.; Tyakht, A.; Kovarsky, B.; Alekseev, D.; Kostryukova, E.; et al. Analysis of gut microbiota in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 162, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintz-Buschart, A.; Pandey, U.; Wicke, T.; Sixel-Döring, F.; Janzen, A.; Sittig-Wiegand, E.; Trenkwalder, C.; Oertel, W.H.; Mollenhauer, B.; Wilmes, P. The nasal and gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease and idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Lyu, N.; Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Liang, S.; Tao, H.; Zhu, B.; Alkasir, R. Analysis of the Gut Microflora in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedarf, J.R.; Hildebrand, F.; Coelho, L.P.; Sunagawa, S.; Bahram, M.; Goeser, F.; Bork, P.; Wüllner, U. Functional implications of microbial and viral gut metagenome changes in early stage L-DOPA-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapała, B.; Stefura, T.; Wójcik-Pędziwiatr, M.; Kabut, R.; Bałajewicz-Nowak, M.; Milewicz, T.; Dudek, A.; Stój, A.; Rudzińska-Bar, M. Differences in the Composition of Gut Microbiota between Patients with Parkinson’s Disease and Healthy Controls: A Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, T.; Gao, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Nie, K. Gut Microbiota Altered in Mild Cognitive Impairment Compared With Normal Cognition in Sporadic Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crost, E.H.; Coletto, E.; Bell, A.; Juge, N. Ruminococcus gnavus: Friend or foe for human health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshavarzian, A.; Green, S.J.; Engen, P.A.; Voigt, R.M.; Naqib, A.; Forsyth, C.B.; Mutlu, E.; Shannon, K.M. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mo, C.; He, X.; Xiao, Q.; Yang, X. Gut microbial community of patients with Parkinson’s disease analyzed using metagenome-assembled genomes. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Arango, L.F.; Barrett, H.L.; Wilkinson, S.A.; Callaway, L.K.; McIntyre, H.D.; Morrison, M.; Dekker Nitert, M. Low dietary fiber intake increases Collinsella abundance in the gut microbiota of overweight and obese pregnant women. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiwaki, H.; Ueyama, J.; Kashihara, K.; Ito, M.; Hamaguchi, T.; Maeda, T.; Tsuboi, Y.; Katsuno, M.; Hirayama, M.; Ohno, K. Gut microbiota in dementia with Lewy bodies. npj Park. Dis. 2022, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Zuo, Y.; Wen, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, T. Impact of exercise training on gut microbiome imbalance in obese individuals: A study based on Mendelian randomization analysis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1264931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, D.; Cai, X.; Xing, X.; Shao, X.; Yin, A.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, M.; Fan, Y.N.; Liu, B.; et al. Gut Commensal Barnesiella Intestinihominis Ameliorates Hyperglycemia and Liver Metabolic Disorders. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2411181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubomski, M.; Xu, X.; Holmes, A.J.; Muller, S.; Yang, J.Y.; Davis, R.L.; Sue, C.M. The gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease: A longitudinal study of the impacts on disease progression and the use of device-assisted therapies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 875261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, X.; Shao, L.; Kong, Q.; Zheng, N.; Ling, Z.; Hu, W. Akkermansia muciniphila in neuropsychiatric disorders: Friend or foe? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1224155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim Neto, D.P.; Bosque, B.P.; Pereira de Godoy, J.V.; Rodrigues, P.V.; Meneses, D.D.; Tostes, K.; Costa Tonoli, C.C.; Faustino de Carvalho, H.; González-Billault, C.; de Castro Fonseca, M. Akkermansia muciniphila induces mitochondrial calcium overload and α -synuclein aggregation in an enteroendocrine cell line. iScience 2022, 25, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Wang, G.; Gong, J.; Yang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Li, D.; Sheng, S.; Zhang, F. Akkermansia muciniphila protects against dopamine neurotoxicity by modulating butyrate to inhibit microglia-mediated neuroinflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 152, 114374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, S.K.; Finseth, T.; Sillau, S.H.; Berman, B.D. Progression of MDS-UPDRS scores over five years in de novo Parkinson disease from the Parkinson’s progression markers initiative cohort. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2018, 5, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrucci, D.; Cerroni, R.; Unida, V.; Farcomeni, A.; Pierantozzi, M.; Mercuri, N.B.; Biocca, S.; Stefani, A.; Desideri, A. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in a selected population of Parkinson’s patients. Park. Relat. Disord. 2019, 65, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Huang, P.; Li, B.; Du, J.; He, Y.; Su, B.; Xu, L.-M.; Wang, L.; et al. Gut metagenomics-derived genes as potential biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2020, 143, 2474–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallen, Z.D.; Appah, M.; Dean, M.N.; Sesler, C.L.; Factor, S.A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C.P.; Standaert, D.G.; Payami, H. Characterizing dysbiosis of gut microbiome in PD: Evidence for overabundance of opportunistic pathogens. npj Park. Dis. 2020, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Siles, M.; Duncan, S.H.; Garcia-Gil, L.J.; Martinez-Medina, M. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: From microbiology to diagnostics and prognostics. ISME J. 2017, 11, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, M.S.; Suvorova, I.A.; Iablokov, S.N.; Petrov, S.N.; Rodionov, D.A. Genomic reconstruction of short-chain fatty acid production by the human gut microbiota. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 949563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Besten, G.; van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Bakker, B.M. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depommier, C.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Plovier, H.; Van Hul, M.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Falony, G.; Raes, J.; Maiter, D.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: A proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, Z.; Deng, L.; Lu, Z.; Wu, F.; Liu, W.; Huang, D.; Peng, Y. Protective effects of Akkermansia muciniphila on cognitive deficits and amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nutr. Diabetes 2020, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donskey, C.J.; Chowdhry, T.K.; Hecker, M.T.; Hoyen, C.K.; Hanrahan, J.A.; Hujer, A.M.; Hutton-Thomas, R.A.; Whalen, C.C.; Bonomo, R.A.; Rice, L.B. Effect of antibiotic therapy on the density of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in the stool of colonized patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerroni, R.; Pietrucci, D.; Teofani, A.; Chillemi, G.; Liguori, C.; Pierantozzi, M.; Unida, V.; Selmani, S.; Mercuri, N.B.; Stefani, A. Not just a snapshot: An Italian longitudinal evaluation of stability of gut microbiota findings in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wu, J.; Dong, X.; Yin, H.; Shi, X.; Su, S.; Che, B.; Li, Y.; Yang, J. Gut flora-targeted photobiomodulation therapy improves senile dementia in an Aß-induced Alzheimer’s disease animal model. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2021, 216, 112152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.H.; Kwon, J.; Do, E.-J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, E.S.; Jeong, J.-Y.; Bae, S.M.; Kim, S.-Y.; Park, D.H. Duodenal Dual-Wavelength Photobiomodulation Improves Hyperglycemia and Hepatic Parameters with Alteration of Gut Microbiome in Type 2 Diabetes Animal Model. Cells 2022, 11, 3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Balsells, A.; Borràs-Pernas, S.; Flotta, F.; Chen, W.; Del Toro, D.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Alberch, J.; Blivet, G.; Touchon, J.; Xifró, X.; et al. Brain–gut photobiomodulation restores cognitive alterations in chronically stressed mice through the regulation of Sirt1 and neuroinflammation. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 354, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Banstola, A.; Bhayana, B.; Wu, M.X. Photobiomodulation strengthens muscles via its dual functions in gut microbiota. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e11582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Shi, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Hu, J.; Dong, X.; Chen, H.; Dai, J.; Yin, H. Gut Microbiota-Targeted Photobiomodulation Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Pathology via the Gut–Brain Axis: Comparable Efficacy to Transcranial Irradiation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khramov, R.N.; Zalomova, L.V.; Fesenko, E.E., Jr. Study of the Effect of Photobiomodulation on the Human Intestinal Microbiota in vitro During Normal and Post-Cryopreservation. Biophysics 2025, 70, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.D.S.; Salehpour, F.; Coimbra, N.C.; Gonzalez-Lima, F.; Gomes da Silva, S. Photobiomodulation for the treatment of neuroinflammation: A systematic review of controlled laboratory animal studies. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1006031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Balah, O.F.; Rafie, M.; Osama, A.-R. Immunomodulatory effects of photobiomodulation: A comprehensive review. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Jo, J.; Shin, H.; Kang, H.W. Therapeutic potential of wavelength-dependent photobiomodulation on gut inflammation in an in vitro intestinal model. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2025, 269, 113201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamblin, M.R. Mechanisms and applications of the anti-inflammatory effects of photobiomodulation. AIMS Biophys. 2017, 4, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, A.M.; Zorzo, C.; Gutiérrez-Menéndez, A.; Arias, J.L.; Arias, N. Transabdominal photobiomodulation applications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2025, 26, e13921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, T.M.; Sabino, C.P.; Ribeiro, M.S. Photobiomodulation reduces abdominal adipose tissue inflammatory infiltrate of diet-induced obese and hyperglycemic mice. J. Biophotonics 2016, 9, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Yang, M.; Yue, N.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, C.; Wei, D.; Shi, R.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.; Li, D. Restore Intestinal Barrier Integrity: An Approach for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Therapy. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 5389–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, E.; Geetha, T.; Burnett, D.; Babu, J.R. The Role of Diet and Dietary Patterns in Parkinson’s Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegelmaier, T.; Lebbing, M.; Duscha, A.; Tomaske, L.; Tönges, L.; Holm, J.B.; Bjørn Nielsen, H.; Gatermann, S.G.; Przuntek, H.; Haghikia, A. Interventional Influence of the Intestinal Microbiome Through Dietary Intervention and Bowel Cleansing Might Improve Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, H.; Sedighi, S.; Kouchaki, E.; Barati, E.; Dadgostar, E.; Aschner, M.; Tamtaji, O.R. Probiotics and the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease: An Update. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 42, 2449–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Lai, H.-C.; Wu, M.-S. Gut-oriented disease modifying therapy for Parkinson’s disease. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2023, 122, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhao, F.; Liu, Y.; Ma, T.; Jin, H.; Quan, K.; Leng, B.; Zhao, J.; Yuan, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Probiotics synergized with conventional regimen in managing Parkinson’s disease. npj Park. Dis. 2022, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.H.; Hor, J.W.; Chong, C.W.; Lim, S.Y. Probiotics for Parkinson’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. JGH Open 2021, 5, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, S.; Rao, S.; Khattak, A.; Zamir, F.; Chaari, A. Physical Exercise and the Gut Microbiome: A Bidirectional Relationship Influencing Health and Performance. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekar, S.; Venkatachalapathy, R.; Jayaraman, A.; Sai Supra Siddhu, N. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of clinical evidence. Med. Microecol. 2025, 25, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Tan, G.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, C.; Ruan, G.; Ying, S.; Qie, J.; Hu, X.; Xiao, Z.; Xu, F.; et al. Efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Clinical trial results from a randomized, placebo-controlled design. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2284247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sciscio, M.; Bryant, R.V.; Haylock-Jacobs, S.; Day, A.S.; Pitchers, W.; Iansek, R.; Costello, S.P.; Kimber, T.E. Faecal microbiota transplant in Parkinson’s disease: Pilot study to establish safety & tolerability. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.S.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. The gut microbiome as a modulator of healthy ageing. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Benayoun, B.A. The microbiome: An emerging key player in aging and longevity. Transl. Med. Aging 2020, 4, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Zhang, K.; Paul, K.C.; Folle, A.D.; Del Rosario, I.; Jacobs, J.P.; Keener, A.M.; Bronstein, J.M.; Ritz, B. Diet and the gut microbiome in patients with Parkinson’s disease. npj Park. Dis. 2024, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | |||||||

| A2 | A5 | B1 | B2 | B4 | B5 | ||

| Sex | F | M | F | F | M | F | |

| Age | Baseline | 79 | 72 | 58 | 77 | 75 | 67 |

| 5 years | 84 | 77 | 63 | 82 | 80 | 72 | |

| Years since diagnosis at baseline | 1 | not reported | 3 | 7 | 2 | 7 | |

| Hoehn and Yahr stage | Baseline | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 5 years | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| Affected side | L | L | L | L | L | R | |

| Medications | Madopar bd HBS nocte | Sinemet 7 × d Sifrol mane | Kinson 7 × d | Kinson QID | Madopar bd | Stalevo QID | |

| Daily L-dopa | 600 mg | 700 mg | 170 mg | 400 mg | 600 mg | 800 mg | |

| MDS-UPDRS-III SCORE | Baseline | 20 | 15 | 23 | 54 | 18 | 20 |

| 5 years | 24 | 15 | 21 | 23 | 12 | 19 | |

| Falls in 5 years | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Change in sense of smell | Improvement from hyposmia | Unchanged | Slow improvement | Substantial improvement from >5 years of anosmia | Improvement from anosmia | Slowly deteriorating | |

| Major dietary changes over 5 yrs | No | No | ? less healthy after year 2 | No | No | Reduced carbohydrates 2 years into study | |

| Exercise | Bike 20 min/day | Unanswered | Bike 30–40 km/week | Gardening + incidental (stairs) | Walking 5–6000 steps/day | PD-specific exercises 1× per week | |

| Helmet used | SYMBYX | VIELIGHT | SYMBYX | WELL RED | VIELIGHT | SYMBYX | |

| Taxa | Functional Relevance | Change in PD vs. HCs | Change over 5 Years | Mean % in | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incr. | Decr. | nc | nd | Microbiome | |||

| Phylum | |||||||

| Bacillota | Contains many SCFA producers | Often depleted [8,10] | 2 | 4 | - | 17.055 | |

| Actinomycetota | Mixed functions, some beneficial | 6 | 0 | - | 17.550 | ||

| Bacteroidota | Contains SCFA producers as well as pathobionts | Can be enriched [8,46] or depleted [47] | 2 | 4 | - | 9.832 | |

| Pseudomonadota | Contains many pathobionts | Enriched in PD [48] | 2 | 4 | - | 0.762 | |

| Desulfobacterota | H2S-producing bacteria | Enriched in PD [49] | 1 | 5 | - | 0.206 | |

| Methanobacteriota | CH4-producing | Enriched in PD [9] | 2 | 4 | - | 0.862 | |

| Family | |||||||

| Ruminococcaceae | Contains SCFA producers | Can be depleted [50] or enriched [11] | 3 | 3 | - | 7.500 | |

| Bifidobacteriaceae | Contains SCFA producers, anti-inflammatory, contains probiotic species | Often enriched [38,51] | 5 | 1 | - | 12.501 | |

| Enterobacteriaceae | Gram-negative, LPS producers, implicated in neuroinflammation | Often enriched [10] | 1 | 2 | - | 3 | 0.123 |

| Desulfovibrionaceae | H2S producers | Enriched [52], linked to α-synuclein aggregation [52] | 0 | 5 | 1 | - | 0.205 |

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Contains SCFA producers, increased in inflammatory diseases [53] and disrupted lipid metabolism [54] | Enriched [38] or depleted [55], correlated with worsening UPDRS-III [38] | 1 | 5 | - | 0.868 | |

| Genus | |||||||

| SCFA Producers Reported as Reduced in PD Compared to HCs | |||||||

| Faecalibacterium | Key SCFA producer, anti-inflammatory, supports gut barrier, reduces systemic and neuroinflammation | Depleted in PD [56,57,58] | 4 | 1 | 1 | - | 3.019 |

| Anaerostipes | SCFA producer | Depleted [9], protective against PD [59] | 0 | 2 | 4 | - | 2.635 |

| Blautia | SCFA producer | Reduced in PD [60], negatively associated with PD severity [61] | 1 | 2 | 3 | - | 13.194 |

| Roseburia_A | SCFA producers, anti-inflammatory, reduces systemic and neuroinflammation | Reduced in PD [60] | 0 | 5 | - | 1 | 0.872 |

| Roseburia_C | 0 | 4 | - | 2 | 0.149 | ||

| Coprococcus_A_187866 | SCFA producers, anti-inflammatory | Reduced in PD [60] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.275 |

| Coprococcus_A_121497 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0.265 | ||

| SCFA Producers Reported as Increased in PD Compared to HCs | |||||||

| Bifidobacterium | SCFA producer, enhances tight junctions [62], neuroprotective in other models | Often enriched [8], but low levels found correlated with faster progression [63] | 4 | 0 | 2 | - | 12.498 |

| Alistipes | SCFA producer, mixed roles, beneficial and detrimental (IBD) effects [64] | Often enriched [9] | 2 | 4 | - | - | 1.169 |

| Parabacteroides | SCFA producer, anti-inflammatory in the microbiome | Can be enriched [65] | 1 | 4 | 1 | - | 1.486 |

| SCFA Producers Reported as Either Reduced or Increased in PD Compared to HCs | |||||||

| Gemmiger | SCFA producer | Sometimes enriched [66], other times depleted | 1 | 3 | 2 | - | 3.533 |

| Prevotella | Some strains related to dysbiosis, SCFA producer | Can be depleted [67] or enriched [68], inversely correlated with disease progression [34] | 3 | 0 | - | 3 | 0.622 |

| Turicibacter | SCFA producer, modifies bile acids, reduces cholesterol and triglycerides (mice) | Depleted [16] or enriched [69] | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.065 | |

| Eubacterium_R | SCFA producers, mixed species | Depleted [70] or enriched [71], some species correlated with higher UPDRS [70] | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.630 |

| Eubacterium_J | 1 | 3 | - | 2 | 0.364 | ||

| Eubacterium_G | 1 | 5 | - | - | 0.163 | ||

| Eubacterium_F | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.083 | ||

| Eubacterium_I | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.078 | ||

| Butyricimonas | SCFA producers | Enriched in PD [71], higher abundance correlated with worse cognitive symptoms [72] but better non-motor symptoms in one study [45] | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.054 |

| Ruminococcus_B | SCFA producers, strain-specific interactions in health and disease [73] | Can be depleted [69] or enriched in PD [42] | 0 | 4 | - | 2 | 0.234 |

| Ruminococcus_E | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.042 | ||

| Bacteroides | SCFA producers, some pro-inflammatory strains | Enriched [74] or depleted [67] in PD, low levels correlated with faster progression [63] | 2 | 4 | - | - | 5.051 |

| Pathobionts—Reported as Enriched in PD Compared to HCs | |||||||

| Streptococcus | Pathobiont | Enriched in PD [8] | 1 | 0 | 5 | - | 2.381 |

| Limiplasma | Unknown | Enriched in PD [9], correlated with PD severity [75] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.375 |

| Collinsella | Related to a high-protein and low-fibre diet [76], may be pro-inflammatory | Enriched in PD in some studies [36,66], depleted in one Indian study [37], related to Lewy Body dementia [77], correlated with faster PD progression [35] | 5 | 1 | - | - | 3.905 |

| Methanobrevibacter | Archean CH4 producer | Enriched in PD [9] | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.190 |

| Klebsiella | LPS producer | Enriched in PD [65] | 1 | 2 | - | 3 | 0.110 |

| Bilophila | H2S producer | Correlated with PD progression [35] | 1 | 3 | - | 2 | 0.059 |

| Desulfovibrio | H2S producer | Enriched, correlated with worsened MDS-UPDRS-III and IV [38] | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.139 |

| Holdemania | Associated with obesity [78] | Over-represented in PD [42] | 0 | 6 | - | - | 0.054 |

| Other Genera | |||||||

| Barnesiella | Mixed effects, may ameliorate T2D [79] | Reduced abundance correlated with faster PD progression [80] | 3 | 3 | - | 0.402 | |

| Akkermansia | Mucin degrader, gut barrier support [81] | Often enriched [35], may induce α-synuclein in vitro [82], neuroprotective in a mouse model of PD [83] | 2 | 4 | - | - | 2.234 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bicknell, B.; Liebert, A.; McLachlan, C.; Kiat, H. Five-Year Follow-Up of Photobiomodulation in Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Series Exploring Clinical Stability and Microbiome Modulation. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010368

Bicknell B, Liebert A, McLachlan C, Kiat H. Five-Year Follow-Up of Photobiomodulation in Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Series Exploring Clinical Stability and Microbiome Modulation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):368. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010368

Chicago/Turabian StyleBicknell, Brian, Ann Liebert, Craig McLachlan, and Hosen Kiat. 2026. "Five-Year Follow-Up of Photobiomodulation in Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Series Exploring Clinical Stability and Microbiome Modulation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010368

APA StyleBicknell, B., Liebert, A., McLachlan, C., & Kiat, H. (2026). Five-Year Follow-Up of Photobiomodulation in Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Series Exploring Clinical Stability and Microbiome Modulation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010368