The Role of Personal Values in the Context of the Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Satisfaction with Life in the Group of Uniformed Personnel Treated in a Mental Health Clinic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure and Ethics

2.4. Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

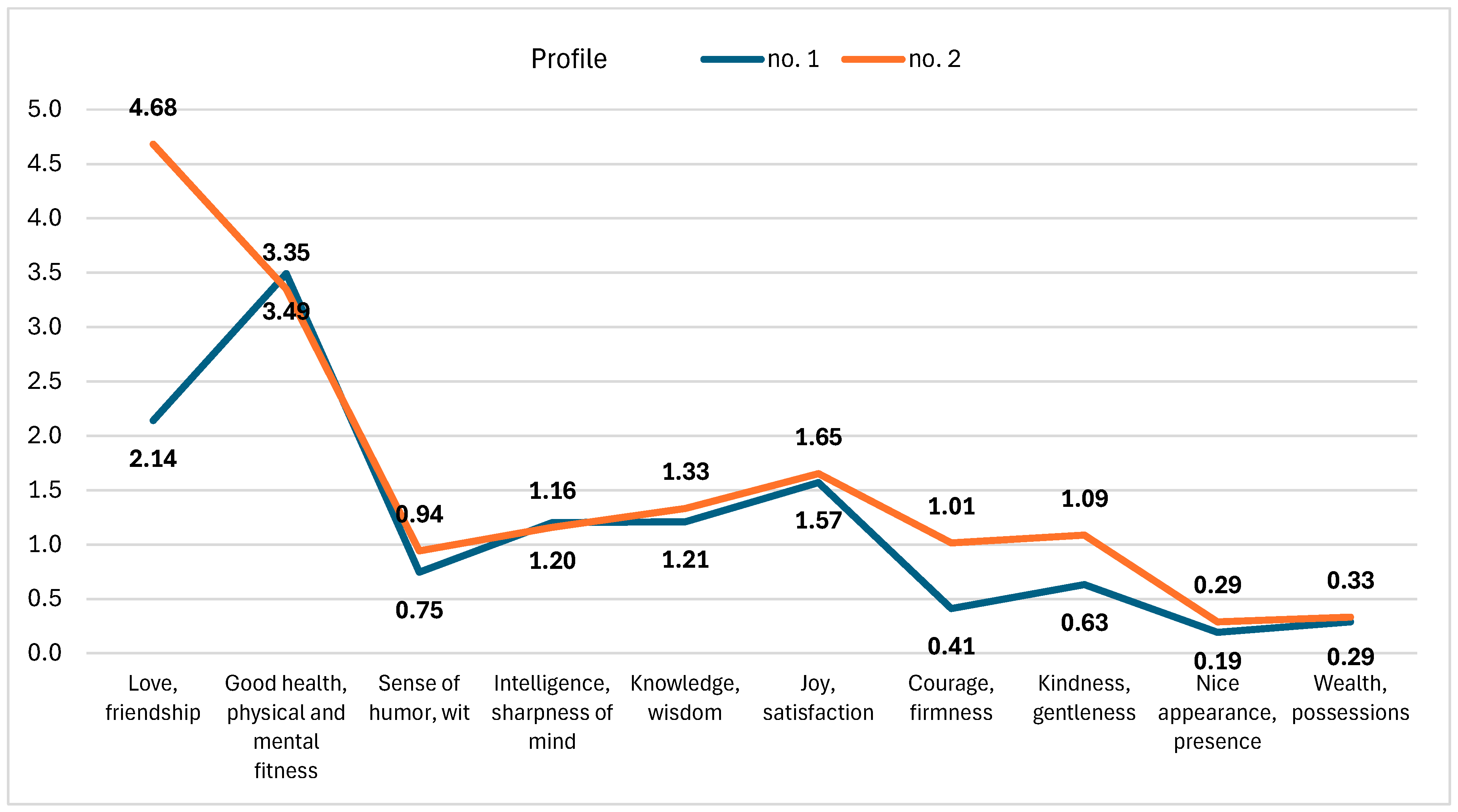

3.2. Latent Profile Analysis

3.3. Moderation Analysis

3.4. Personal Values Hierarchy and Stress Coping Styles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Implement interventions, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) or Motivational Interviewing, to align coping strategies with adaptive values, as personal values are related to coping;

- Use follow-up assessments of value hierarchies and coping styles to guide ongoing treatment and detect early warning signs of maladaptive coping, as perceived stress is related to satisfaction with life;

- Provide mental health professionals with training in value-oriented approaches to strengthen therapeutic alliance and enhance treatment outcomes, as personal values are related to stress coping.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juczyński, Z. Health in the Hierarchy of Personal Values of Children and Youth. Pedagog. Rodz. 2014, 4, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, R.A.R. Health Psychology: Well-Being in a Diverse World; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, N.; Bhau, S. A Comparative Study of Levels of Perceived Stress, Life Satisfaction and Quality of Life among Mental Health Professionals and Non-mental Health Professionals in India. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2023, 14, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Endler, N.S. Coronary Heart Disease (CHD); Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Pergamon, Turkey, 2001; pp. 2770–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, N.S. Stress, anxiety and coping: The multidimensional interaction model. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 1997, 38, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, J.; Lopez, K.J. Labor, Depletion, and Disconnection: Leisure as Restoration for Uniformed Public Safety Personnel. Leis. Sci. 2025, 47, 1595–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivar, L.S.; Valera, M.A.B.; Ocampo, D.L.; de Torres, M.J.R.; Gonzales, R.J.E.; Yabut, G.C.; Villa, E.B. Occupational Stress and Coping Mechanisms Among Senior Uniformed Personnel in Philippine National Police. Int. J. Multidiscip. Appl. Bus. Educ. Res. 2024, 5, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingräber, A.-M.; Tübben, N.; Brinkmann, N.; Finkeldey, F.; Migutin, S.; Bürger, A.; Laubstein, A.; Abel, B.; von Lüdinghausen, N.; Herzberg, P.Y.; et al. Contributions to operational psychology: Psychological training model in the context of stress management for specialized German military police personnel and specialized police personnel. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2022, 37, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, K.; Hurtado, S.L.; Yablonsky, A.M. Evaluation of a Stress Management Course for Shipboard Sailors. Mil. Med. 2023, 188, e503–e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.H.; Park, S.S.; Hong, C.W.; Kwon, K.T.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, K.S.; Choi, H.; et al. Investigating the effect of mindfulness training for stress management in military training: The relationship between the autonomic nervous system and emotional regulation. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Heeringa, S.G.; Stein, M.B.; Colpe, L.J.; Fullerton, C.S.; Hwang, I.; Naifeh, J.A.; Nock, M.K.; Petukhova, M.; Sampson, N.A.; et al. Thirty-Day Prevalence of DSM-IV Mental Disorders Among Nondeployed Soldiers in the US Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruby, A.; Lieberman, H.R.; Smith, T.J. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder and their relationship to health-related behaviors in over 12,000 US military personnel: Bi-directional associations. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 283, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. The Global Standard for Diagnostic Health Information. Available online: https://icd.who.int/en/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Endler, N.S.; Parker, J.D.A. Multidimensional Assessment of Coping: A Critical Evaluation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strelau, J.; Jaworowska, A.; Wrześniewski, K.; Szczepaniak, P. CISS—Coping in Stressful Situations; Manual; PTP: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Juczynski, Z.; Oginska-Bulik, N. Tools for Measuring Stress and Coping with Stress; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi, Version 2.3; Jamovi: Sydney, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Zalewska, A.M.; Zwierzchowska, M. Personality Traits, Personal Values, and Life Satisfaction among Polish Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemay, E.P., Jr.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Molinario, E.; Agostini, M.; Bélanger, J.J.; Gützkow, B.; Kreienkamp, J.; Margit Reitsema, A.R.; vanDellen, M.; PsyCorona Collaboration; et al. The role of values in coping with health and economic threats of COVID-19. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 163, 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamila, A.; Turana, A.; Rashid, J.; Mammadli, I. Students’ Values and Their Mental Health during Pandemic. J. Educ. Psychol. Propos. Represent. 2021, 9, e1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaveanu, S.M.; Prisăcaru, A.; Ungureanu, G. Psychological Resilience in Relation to the Coping Strategies and Individual Values of the Students—Diagnosis and Intervention Measures. Euromentor 2023, 14, 9–32. [Google Scholar]

| Gender | Education | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Secondary | Higher | |

| n | 34 (18.6%) | 149 (81.4%) | 89 (48.6%) | 94 (51.4%) |

| M | 46.94 | 44.21 | 45.55 | 44.17 |

| SD | 8.38 | 4.99 | 6.11 | 6.12 |

| min | 30 | 33 | 33 | 30 |

| max | 66 | 57 | 66 | 60 |

| Variables | M | SD | min | max | S | K | S-W | p | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress coping styles | |||||||||

| Task-oriented style | 53.60 | 11.26 | 13 | 75 | −1.51 | 3.65 | 0.87 | <0.001 | 0.88 |

| Emotion-oriented style | 42.60 | 11.47 | 10 | 66 | −0.37 | 0.06 | 0.98 | 0.031 | 0.91 |

| Avoidant style | 42.10 | 9.89 | 16 | 62 | −0.61 | 0.33 | 0.97 | <0.0001 | 0.83 |

| Distraction seeking | 19.30 | 5.13 | 8 | 31 | −0.10 | −0.59 | 0.99 | 0.073 | 0.76 |

| Social diversion | 14.80 | 4.25 | 2 | 23 | −0.72 | 0.50 | 0.96 | <0.001 | 0.75 |

| Perceived stress | 19.30 | 6.38 | 5 | 37 | −0.02 | −0.30 | 0.99 | 0.293 | 0.88 |

| Satisfaction with life | 21.00 | 5.49 | 5 | 33 | −0.19 | −0.28 | 0.99 | 0.065 | 0.76 |

| Personal values | |||||||||

| Love, friendship | 3.10 | 2.02 | 0 | 5 | −0.63 | −1.32 | 0.77 | <0.001 | - |

| Good health, physical and mental fitness | 3.44 | 1.86 | 0 | 5 | −0.96 | −0.61 | 0.76 | <0.001 | - |

| Sense of humor, wit | 0.82 | 1.42 | 0 | 6 | 1.71 | 1.83 | 0.64 | <0.001 | - |

| Intelligence, sharpness of mind | 1.19 | 1.64 | 0 | 10 | 1.47 | 3.33 | 0.72 | <0.001 | - |

| Knowledge, wisdom | 1.26 | 1.44 | 0 | 5 | 0.73 | −0.72 | 0.80 | <0.001 | - |

| Joy, satisfaction | 1.60 | 1.57 | 0 | 8 | 0.67 | 0.14 | 0.85 | <0.001 | - |

| Courage, firmness | 0.64 | 1.13 | 0 | 5 | 1.82 | 2.48 | 0.63 | <0.001 | - |

| Kindness, gentleness | 0.80 | 1.34 | 0 | 6 | 1.63 | 1.75 | 0.66 | <0.001 | - |

| Nice appearance, presence | 0.23 | 0.93 | 0 | 9 | 6.02 | 46.14 | 0.27 | <0.001 | - |

| Wealth, possessions | 0.31 | 0.90 | 0 | 5 | 3.50 | 12.35 | 0.39 | <0.001 | - |

| Effect | B | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived stress | −0.36 [−0.48; −0.24] | −5.68 | <0.001 |

| Personal values—profile no. 1 or no. 2 | 0.44 [−1.22; 2.07] | 0.53 | 0.595 |

| Moderation effect | 0.01 [−0.26; 0.26] | 0.12 | 0.907 |

| Profile of Personal Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. 1 | No. 2 | ||||||

| Stress Coping Styles | M | SD | M | SD | F | df | p |

| Task-oriented style | 53.70 | 9.88 | 53.50 | 13.30 | 0.01 | 1180 | 0.918 |

| Emotion-oriented style | 42.80 | 11.00 | 42.40 | 12.30 | 0.05 | 1180 | 0.822 |

| Avoidant style | 43.00 | 9.14 | 40.60 | 10.90 | 2.65 | 1180 | 0.105 |

| Distraction seeking | 20.00 | 4.73 | 18.00 | 5.53 | 6.75 | 1180 | 0.010 |

| Social diversion | 14.80 | 4.06 | 14.80 | 4.58 | 0.00 | 1180 | 0.980 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Curyło, M.; Zabojszcz, M.; Tkaczyk, L.; Iwolska, J.; Mikos, M.; Strzępek, Ł.; Czerw, A.; Charkiewicz, D.; Partyka, O.; Pajewska, M.; et al. The Role of Personal Values in the Context of the Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Satisfaction with Life in the Group of Uniformed Personnel Treated in a Mental Health Clinic. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010369

Curyło M, Zabojszcz M, Tkaczyk L, Iwolska J, Mikos M, Strzępek Ł, Czerw A, Charkiewicz D, Partyka O, Pajewska M, et al. The Role of Personal Values in the Context of the Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Satisfaction with Life in the Group of Uniformed Personnel Treated in a Mental Health Clinic. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):369. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010369

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuryło, Mateusz, Michał Zabojszcz, Lidia Tkaczyk, Jaromira Iwolska, Marcin Mikos, Łukasz Strzępek, Aleksandra Czerw, Dorota Charkiewicz, Olga Partyka, Monika Pajewska, and et al. 2026. "The Role of Personal Values in the Context of the Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Satisfaction with Life in the Group of Uniformed Personnel Treated in a Mental Health Clinic" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010369

APA StyleCuryło, M., Zabojszcz, M., Tkaczyk, L., Iwolska, J., Mikos, M., Strzępek, Ł., Czerw, A., Charkiewicz, D., Partyka, O., Pajewska, M., Sygit, K., Sygit, M., Wysocki, S., Gąska, I., Kaczmar, E., Grochans, E., Cybulska, A. M., Schneider-Matyka, D., Bandurska, E., ... Kozlowski, R. (2026). The Role of Personal Values in the Context of the Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Satisfaction with Life in the Group of Uniformed Personnel Treated in a Mental Health Clinic. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010369