Cross-Sectional Study on Electrocardiographic Disorders in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis in Real-World Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

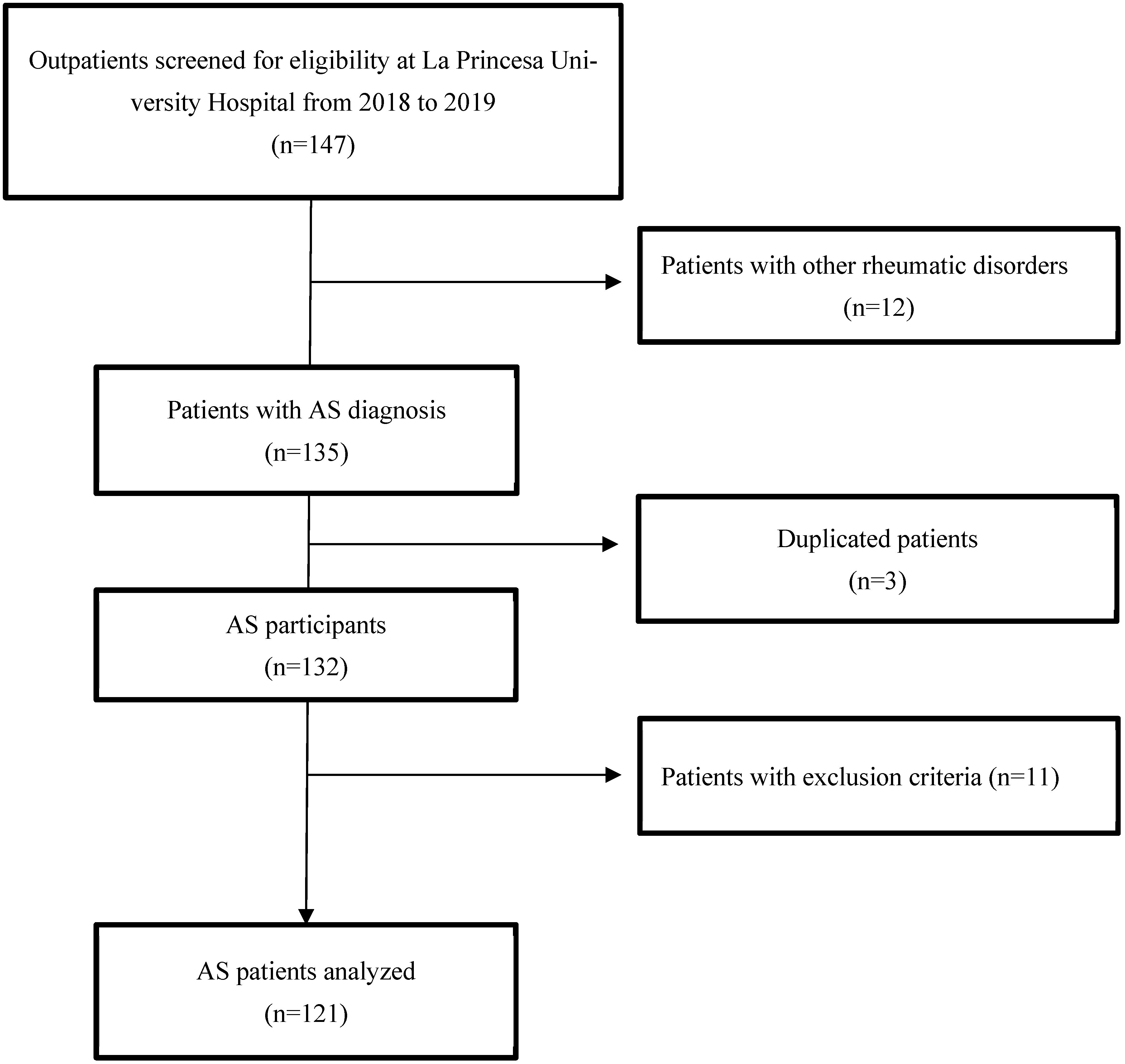

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population and Protocol

2.3. Electrocardiogram Analysis

2.4. Clinical Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Clinical Features of the Patients

3.2. Electric Heart Disorders

| Variables | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjusted Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 1.06 | 1.01–1.10 | 0.008 | |||

| Male sex | 2.37 | 0.62–9.00 | 0.205 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 3.40 | 0.59–19.47 | 0.169 | |||

| Hypertension | 6.13 | 1.79–21.02 | 0.004 | 6.1 | 1.71–21.76 | 0.005 |

| Disease duration (years) | 1.05 | 0.99–1.11 | 0.111 | |||

| ESR, mm/1st h | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.217 | |||

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.87 | 0.43.1.72 | 0.682 | |||

| DMARDs | 0.74 | 0.19–2.93 | 0.670 | |||

| Treatment duration (years) | 1.06 | 1.00–1.13 | 0.037 | 1.07 | 1.00–1.13 | 0.043 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.07 | 0.95–1.19 | 0.292 | |||

| Variables | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjusted Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 1.07 | 1.02–1.12 | 0.005 | 1.07 | 1.01–1.14 | 0.013 |

| Male sex | 0.38 | 0.11–1.29 | 0.120 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 4.16 | 0.71–24.27 | 0.113 | |||

| Hypertension | 4.61 | 1.30–16.37 | 0.018 | NS | ||

| Disease duration (years) | 1.00 | 0.93–1.07 | 0.979 | |||

| ESR, mm/1st h | 0.97 | 0.90–1.04 | 0.341 | |||

| CRP, mg/dL | 1.00 | 0.97–1.04 | 0.804 | |||

| DMARDs | 1.16 | 0.74–1.81 | 0.529 | |||

| Treatment duration (years) | 0.37 | 0.10–1.37 | 0.136 | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.17 | 1.02–1.34 | 0.023 | 1.15 | 0.99–1.33 | 0.071 |

3.3. Comparison with Previous Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| AS | Ankylosing spondylitis |

| AVB | Atrioventricular block |

| BASDAI | Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index |

| BASFI | Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DMARDs | Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EHD | Electric heart disorders |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| IRT | Intranodal reentrant tachycardia |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| RR | Relative risk |

| SpA | Spondyloarthritis/spondyloarthritides |

| SVT | Supraventricular tachyarrhythmia |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

References

- Kim, Y.; Oh, H.C.; Park, J.W.; Kim, I.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, K.C.; Chae, D.S.; Jo, W.L.; Song, J.H. Diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory joint disease. Hip Pelvis 2017, 29, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, J.J.; van Mens, L.J.; van der Heijde, D.; Landewé, R.; Baeten, D.L. Prevalence of peripheral and extra-articular disease in ankylosing spondylitis versus non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: A meta-analysis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2016, 18, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, Y. Cardiac involvement in ankylosing spondylitis. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 8, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoane-Mato, D.; Sánchez-Piedra, C.; Silva-Fernández, L.; Sivera, F.; Blanco, F.J.; Pérez Ruiz, F.; Juan-Mas, A.; Pego-Reigosa, J.M.; Narváez, J.; Quilis Martí, N.; et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in the adult population in Spain (EPISER 2016 study): Objectives and methodology. Reumatol. Clin. 2019, 15, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, F.; Talpin, A.; Said-Nahal, R.; Goldberg, M.; Henny, J.; Chiocchia, G.; Garchon, H.J.; Zins, M.; Breban, M. Prevalence of spondyloarthritis in reference to HLA-B27 in the French population: Results of the GAZEL cohort. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casals-Sánchez, J.L.; García De Yébenes Prous, M.J.; Descalzo Gallego, M.Á.; Barrio Olmos, J.M.; Carmona Ortells, L.; Hernández García, C. Characteristics of patients with spondyloarthritis followed in rheumatology units in Spain: emAR II study. Reumatol. Clin. 2012, 8, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raychaudhuri, S.P.; Deodhar, A. The classification and diagnostic criteria of ankylosing spondylitis. J. Autoimmun. 2014, 48–49, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julià, A.; Martínez-Mateu, S.H.; Domènech, E.; Cañete, J.D.; Ferrándiz, C.; Tornero, J.; Gisbert, J.P.; Fernández-Nebro, A.; Daudén, E.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; et al. Food groups associated with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A Mendelian randomization and disease severity study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 1368–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandour, M.; Chen, S.; van de Sande, M.G.H. The role of the IL-23/IL-17 axis in disease initiation in spondyloarthritis: Lessons learned from animal models. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 618581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schett, G.; McInnes, I.B.; Neurath, M.F. Reframing immune-mediated inflammatory diseases through signature cytokine hubs. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz-Amaro, I.; Genre, F.; Blanco, R.; Calvo-Rio, V.; Corrales-Selaya, C.; Portilla, V.; Aurrecoechea, E.; Batanero, R.; Hernández-Hernández, V.; Quevedo-Abeledo, J.C.; et al. Sex-specific impact of inflammation on traditional cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in axial spondyloarthritis: A multicentre study of 913 patients. RMD Open 2024, 10, e004187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, S.; Martín-Martínez, M.A.; González-Juanatey, C.; Llorca, J.; García-Yébenes, M.J.; Pérez-Vicente, S.; Sánchez-Costa, J.T.; Díaz-Gonzalez, F.; González-Gay, M.A. Cardiovascular morbidity and associated risk factors in Spanish patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases attending rheumatology clinics: Baseline data of the CARMA project. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015, 44, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, S.; Nurmohamed, M.T.; González-Gay, M.A. Cardiovascular disease in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 30, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Pan, Z.; Fan, D.; Xu, S.; Pan, F. The increased risk of atrial fibrillation in inflammatory arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Immunol. Investig. 2022, 51, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, M.J.; Geurts, S.; Zhu, F.; Bos, M.M.; Ikram, M.A.; de Maat, M.P.M.; de Groot, N.M.S.; Kavousi, M. Autoimmune diseases and new-onset atrial fibrillation: A UK Biobank study. Europace 2023, 25, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, S.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, C.; Gonzalez-Gay, M.A. Inflammatory arthritis and heart disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzerini, P.E.; Capecchi, P.L.; Laghi-Pasini, F. Systemic inflammation and arrhythmic risk: Lessons from rheumatoid arthritis. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, M.; van Wagoner, D.R.; Nattel, S. Role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation pathophysiology and management. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengtsson, K.; Forsblad-d’Elia, H.; Lie, E.; Klingberg, E.; Dehlin, M.; Exarchou, S.; Lindström, U.; Askling, J.; Jacobsson, L.T.H. Risk of cardiac rhythm disturbances and aortic regurgitation in different spondyloarthritis subtypes in comparison with the general population: A register-based study from Sweden. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, I.; Choi, E.K.; Jung, J.H.; Han, K.D.; Choi, Y.J.; Park, J.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, E.; Choe, W.; Lee, S.R.; et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: A novel risk factor for atrial fibrillation—A nationwide population-based study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 275, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morovatdar, N.; Watts, G.F.; Bondarsahebi, Y.; Goldani, F.; Rahmanipour, E.; Rezaee, R.; Sahebkar, A. Ankylosing spondylitis and risk of cardiac arrhythmia and conduction disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 17, e150521193326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Sijl, A.M.; van Eijk, I.C.; Peters, M.J.; Serné, E.H.; van der Horst-Bruinsma, I.E.; Smulders, Y.M.; Nurmohamed, M.T. Tumour necrosis factor blocking agents and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S.; Valkenburg, H.A.; Cats, A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1984, 27, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GGlikson, M.; Nielsen, J.C.; Kronborg, M.B.; Michowitz, Y.; Auricchio, A.; Barbash, I.M.; Barrabés, J.A.; Boriani, G.; Braunschweig, F.; Brignole, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3427–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Doblas, J.J.; Muñiz, J.; Alonso Martin, J.J.; Rodríguez-Roca, G.; Lobos, J.M.; Awamleh, P.; Permanyer-Miralda, G.; Chorro, F.J.; Anguita, M.; Roig, E.; et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in Spain: Results of the OFRECE study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2014, 67, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aro, A.L.; Anttonen, O.; Kerola, T.; Junttila, M.J.; Tikkanen, J.T.; Rissanen, H.A.; Reunanen, A.; Huikuri, H.V. Prognostic significance of prolonged PR interval in the general population. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genre, F.; López-Mejías, R.; Miranda-Filloy, J.A.; Ubilla, B.; Carnero-López, B.; Blanco, R.; Pina, T.; González-Juanatey, C.; Llorca, J.; González-Gay, M.A. Adipokines, biomarkers of endothelial activation, and metabolic syndrome in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 860651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graßmann, S.; Wirsching, J.; Eichelmann, F.; Aleksandrova, K. Association between peripheral adipokines and inflammation markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity 2017, 25, 1776–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, V.; Danda, D. Inflammation, metabolism and adipokines: Toward a unified theory. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 19, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Liu, L.; Que, W.; Lu, D.; Jing, S.; Gan, Y.; Liu, S.; Xiao, F. Association of regional adiposity distribution with risk of autoimmune diseases. Clin. Rheumatol. 2025, 44, 2541–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, T.; Hadizadeh, F.; Rask-Andersen, M.; Johansson, Å.; Ek, W.E. Body mass index and the risk of rheumatic disease: Linear and nonlinear Mendelian randomization analyses. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75, 2027–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, Z.; Oldgren, J.; Siegbahn, A.; Wallentin, L. Application of biomarkers for risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalta, T.; Yalta, K. Systemic inflammation and arrhythmogenesis: A review of mechanistic and clinical perspectives. Angiology 2018, 69, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, I.M.; Gibson, D.S.; McGilligan, V.; McNerlan, S.E.; Alexander, H.D.; Ross, O.A. Age and age-related diseases: Role of inflammation triggers and cytokines. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadic, M.; Cuspidi, C. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation: From mechanisms to clinical practice. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 108, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusinowicz, T.; Zielonka, T.M.; Zycinska, K. Cardiac arrhythmias in patients with exacerbation of COPD. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1022, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimetbaum, P. Atrial fibrillation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, ITC33–ITC48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tse, G.; Zhang, L.; Wan, E.Y.; Guo, Y.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Li, G.; Lu, Z.; Liu, T.; et al. Cardiac arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19. J. Arrhythm. 2020, 36, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathannair, R.; Olshansky, B.; Chung, M.K.; Gordon, S.; Joglar, J.A.; Marcus, G.M.; Mar, P.L.; Russo, A.M.; Srivatsa, U.N.; Wan, E.Y.; et al. Cardiac arrhythmias and autonomic dysfunction associated with COVID-19: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 150, e449–e465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.S.; Rashid, M.; Beynon, R.; Barker, D.; Patwala, A.; Morley-Davies, A.; Satchithananda, D.; Nolan, J.; Myint, P.K.; Buchan, I.; et al. Prolonged PR interval, first-degree heart block and adverse cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2016, 102, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Overall Cohort (n = 121) | Arrythmia (n = 11) | No Arrythmia (n = 110) | p-Value | Conduction Delays (n = 14) | No Conduction Delays (n = 107) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 76 (62.8) | 4 (36.4) | 72 (65.5) | 0.098 | 11 (78.6) | 65 (60.8) | 0.248 |

| Age (years) | 54.6 ± 15.6 | 66.5 ± 16.4 | 53.4 ± 15.1 | 0.003 | 65.4 ± 13.6 | 53.1 ± 15.4 | 0.003 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.9 ± 4.8 | 30.3 ± 6.0 | 26.5 ± 4.5 | 0.009 | 28.2 ± 4.2 | 26.7 ± 4.9 | 0.146 |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 25 (20.7) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (22.7) | 0.075 | 1 (7.1) | 24 (22.4) | 0.223 |

| Daily physical activity, n (%) | 88 (76.5) | 9 (81.8) | 79 (76.0) | 1 | 9 (10.2) | 79 (88.7) | 0.5 |

| HLA B27 positive | 92 (82.1) | 9 (81.8) | 83 (82.2) | 1 | 12 (85.7) | 80 (81.6) | 1 |

| AS-related comorbidities | |||||||

| -Uveitis, n (%) | 19 (15.7) | 1 (9.1) | 18 (16.4) | 0.485 | 2 (14.3) | 17 (15.9) | 1 |

| -Inflammatory bowel disease, n (%) | 13 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (11.8) | 0.601 | 1 (7.1) | 12 (11.2) | 1 |

| Disease duration (years) | 14 (8–20) | 9 (6–17) | 14 (8–21) | 0.194 | 20.5 (19–23) | 14 (7–20) | 0.024 |

| Disease activity parameters | |||||||

| -ESR, mm/1st h, median (IQR) | 8 (4–21) | 6 (5–15) | 8 (4–21.5) | 0.883 | 10.5 (4–24) | 8 (4–21) | 0.801 |

| -CRP, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.686 | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.394 |

| -BASFI (0–100) | 26 (7–39) | 3.5 (0–4.5) | 2.6 (0.7–3.7) | 0.782 | 3.5 (1.9–4.5) | 2.4 (0.6–3.6) | 0.133 |

| -BASDAI (0–100) | 28 (6–55) | 4 (0–6.1) | 2.8 (0.6–4.9) | 0.785 | 3.4 (1.4–5.7) | 2.7 (0.6–5.1) | 0.636 |

| Current treatment | |||||||

| DMARDs, n (%) | 100 (82.6) | 7 (63.64) | 93 (84.6) | 0.098 | 11 (78.6) | 89 (83.2) | 0.709 |

| Sulfasalazine, n (%) | 58 (47.9) | 3 (27.3) | 55 (50) | 0.209 | 4 (28.6) | 54 (50.5) | 0.159 |

| Methotrexate, n (%) | 23 (19.0) | 3 (27.3) | 20 (18.2) | 0.436 | 3 (21.4) | 20 (18.7) | 0.729 |

| Biological drugs, n (%) | 61 (50.4) | 4 (36.4) | 57 (51.8) | 0.363 | 8 (57.1) | 53 (49.5) | 0.592 |

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 5 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.6) | 1 | 1 (7.1) | 4 (3.7) | 0.465 |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 60 (49.6) | 8 (72.7) | 52 (47.3) | 0.126 | 5 (35.71) | 55 (51.4) | 0.270 |

| Treatment duration (years) | 4.5 (0–11.5) | 4 (1–9) | 5 (0–12) | 0.913 | 12 (1–20) | 4 (0–11) | 0.040 |

| Other comorbidities | |||||||

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 7 (5.8) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (5.5) | 0.622 | 1 (7.1) | 6 (5.6) | 0.587 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 41 (33.9) | 7 (63.6) | 34 (30.9) | 0.043 | 10 (71.4) | 31 (29.0) | 0.002 |

| COPD, n (%) | 3 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.7) | 1 | 1 (7.1) | 2 (1.9) | 0.311 |

| OSAHS, n (%) | 9 (7.5) | 1 (9.1) | 8 (7.3) | 0.589 | 1 (7.1) | 8 (7.5) | 1 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 7 (5.8) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (5.5) | 0.496 | 2 (14.3) | 5 (4.7) | 0.186 |

| Electric Heart Disorders in AS Patients | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (5) |

| Atrial flutter or atrial tachycardia | 5 (4.1) |

| Atrioventricular conduction delay | |

| First degree AVB or second degree Mobitz I AVB | 8 (6.6) |

| Second degree Mobitz II or third degree AVB | 1 (0.8) |

| Intraventricular conduction delay | |

| With QRS < 120 ms | 2 (1.7) |

| With QRS > 120 ms | 5 (4.1) |

| Variables | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjusted Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 1.06 | 1.01–1.11 | 0.011 | 1.07 | 1.01–1.13 | 0.017 |

| Male sex | 0.30 | 0.8–1.1 | 0.069 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 1.73 | 0.19–15.9 | 0.626 | |||

| Hypertension | 3.91 | 1.07–14.3 | 0.039 | |||

| Disease duration (years) | 0.95 | 0.88–1.02 | 0.184 | 0.92 | 0.84–1.01 | 0.080 |

| ESR, mm/1st h | 1.00 | 0.96–1.04 | 0.919 | |||

| CRP, mg/dL | 1.19 | 0.76–1.86 | 0.442 | |||

| DMARDs | 0.32 | 0.08–1.21 | 0.094 | |||

| Treatment duration (years) | 0.98 | 0.90–1.06 | 0.573 | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.17 | 1.02–1.34 | 0.028 | 1.18 | 1.01–1.40 | 0.038 |

| Electric Heart Disorders | n | (%) | Prevalence Differences 3 | 95% CI of Difference | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF in general population 1 [26] | 8343 | 4.4 | Reference | ||

| -AF in AS (present series) | 121 | 5.0 | 0.6% | −3.3–4.5 | 0.78 |

| AF in general population [19] | 266,435 | 2.8 | Reference | ||

| -AF in AS [19] | 6448 | 4.1 | 1.3% | 0.8–1.8 | <0.001 |

| -AF in AS (present series) | 121 | 5.0 | 2.2% | −2.0–6.3 | 0.31 |

| AVB grade II–III in general population [19] | 266,435 | 0.3 | Reference | ||

| -AVB grade II–III in AS [19] | 6448 | 0.9 | 0.6% | 0.8–0.4 | <0.001 |

| -AVB grade II–III in AS (present series) | 121 | 0.8 | 0.5% | −1.1–2.1 | 0.52 |

| AVB grade I in general population 2 [27] | 10,785 | 2.1 | Reference | ||

| -AVB grade I in AS (present series) | 121 | 4.1 | 2.0% | −1.52–5.58 | 0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-López, C.; Soler Bonafont, B.; Gamarra, Á.; Díez-Villanueva, P.; Jiménez-Borreguero, L.J.; Uriarte-Ecenarro, M.; Vicente-Rabaneda, E.F.; González-Gay, M.A.; Alfonso, F.; Castañeda, S. Cross-Sectional Study on Electrocardiographic Disorders in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis in Real-World Conditions. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010362

Rodríguez-López C, Soler Bonafont B, Gamarra Á, Díez-Villanueva P, Jiménez-Borreguero LJ, Uriarte-Ecenarro M, Vicente-Rabaneda EF, González-Gay MA, Alfonso F, Castañeda S. Cross-Sectional Study on Electrocardiographic Disorders in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis in Real-World Conditions. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010362

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-López, Carlos, Bárbara Soler Bonafont, Álvaro Gamarra, Pablo Díez-Villanueva, Luis Jesús Jiménez-Borreguero, Miren Uriarte-Ecenarro, Esther F. Vicente-Rabaneda, Miguel A. González-Gay, Fernando Alfonso, and Santos Castañeda. 2026. "Cross-Sectional Study on Electrocardiographic Disorders in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis in Real-World Conditions" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010362

APA StyleRodríguez-López, C., Soler Bonafont, B., Gamarra, Á., Díez-Villanueva, P., Jiménez-Borreguero, L. J., Uriarte-Ecenarro, M., Vicente-Rabaneda, E. F., González-Gay, M. A., Alfonso, F., & Castañeda, S. (2026). Cross-Sectional Study on Electrocardiographic Disorders in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis in Real-World Conditions. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010362