Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting After Open Lumbar Discectomy: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial Using Adequacy of Anesthesia Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Anesthetic Technique

2.2.1. Stage 1

2.2.2. Stage 2

2.2.3. Stage 3—Intraoperative

2.2.4. Stage 4—Postoperatively

2.3. Apfel Score

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AoA | Adequacy of Anesthesia |

| BF | Bupivacaine/fentanyl |

| C | Control |

| DoN | Department of Neurosurgery |

| FNT | Fentanyl |

| GA | General anesthesia |

| IA | Infiltration anesthesia |

| IPPP | Inappropriate postoperative pain perception |

| IROA | Intraoperative rescue opioid analgesics |

| MAP | Mean arterial pressure |

| MF | Morphine |

| NPRS | Numeric pain rating scale |

| OLD | Open lumbar discectomy |

| PACU | Post-anesthesia care unit |

| PONV | Postoperative nausea and vomiting |

| RE | Response entropy |

| RF | Ropivacaine/fentanyl |

| SE | State entropy |

| SPI | Surgical pleth index |

References

- Eberhart, L.H.J.; Mauch, M.; Morin, A.M.; Wulf, H.; Geldner, G. Impact of a Multimodal Anti-Emetic Prophylaxis on Patient Satisfaction in High-Risk Patients for Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anaesthesia 2002, 57, 1022–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, H.; Chae, Y.J.; Kang, S.; Yi, I.K. Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting and Recovery of Heart Rate Variability Following General Anesthesia with Propofol or Sevoflurane: A Randomized, Double-Blind Preliminary Study. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1575865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortier, J.; Chung, F.; Su, J. Unanticipated Admission after Ambulatory Surgery—A Prospective Study. Can. J. Anaesth. 1998, 45, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, R.P.; Lubarsky, D.A.; Phillips-Bute, B.; Fortney, J.T.; Creed, M.R.; Glass, P.S.; Gan, T.J. Cost-Effectiveness of Prophylactic Antiemetic Therapy with Ondansetron, Droperidol, or Placebo. Anesthesiology 2000, 92, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avinash, S.H.; Krishna, H.M. The Impact of the Apfel Scoring System for Prophylaxis of Post-Operative Nausea and Vomiting: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 39, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, T.J.; Belani, K.G.; Bergese, S.; Chung, F.; Diemunsch, P.; Habib, A.S.; Jin, Z.; Kovac, A.L.; Meyer, T.A.; Urman, R.D.; et al. Fourth Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 411–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoicea, N.; Gan, T.J.; Joseph, N.; Uribe, A.; Pandya, J.; Dalal, R.; Bergese, S.D. Alternative Therapies for the Prevention of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Front. Med. 2015, 2, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apfel, C.C.; Heidrich, F.M.; Jukar-Rao, S.; Jalota, L.; Hornuss, C.; Whelan, R.P.; Zhang, K.; Cakmakkaya, O.S. Evidence-Based Analysis of Risk Factors for Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Br. J. Anaesth. 2012, 109, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüsch, D.; Becke, K.; Eberhart, L.H.J.; Franck, M.; Hönig, A.; Morin, A.M.; Opel, S.; Piper, S.; Treiber, H.; Ullrich, L.; et al. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV)—Recommendations for risk assessment, prophylaxis and therapy—Results of an expert panel meeting. Anasthesiol. Intensivmed. Notfallmedizin Schmerzther. AINS 2011, 46, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apfel, C.C.; Läärä, E.; Koivuranta, M.; Greim, C.A.; Roewer, N. A Simplified Risk Score for Predicting Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting: Conclusions from Cross-Validations between Two Centers. Anesthesiology 1999, 91, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivuranta, M.; Läärä, E.; Snåre, L.; Alahuhta, S. A Survey of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anaesthesia 1997, 52, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhart, L.H.J.; Geldner, G.; Hörle, S.; Wulf, H. Prophylaxis and treatment of nausea and vomiting after outpatient ophthalmic surgery. Ophthalmol. Z. Dtsch. Ophthalmol. Ges. 2004, 101, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranke, P.; Apefel, C.C.; Papenfuss, T.; Rauch, S.; Löbmann, U.; Rübsam, B.; Greim, C.A.; Roewer, N. An Increased Body Mass Index Is No Risk Factor for Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. A Systematic Review and Results of Original Data. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2001, 45, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apfel, C.C.; Kranke, P.; Katz, M.H.; Goepfert, C.; Papenfuss, T.; Rauch, S.; Heineck, R.; Greim, C.A.; Roewer, N. Volatile Anaesthetics May Be the Main Cause of Early but Not Delayed Postoperative Vomiting: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Factorial Design. Br. J. Anaesth. 2002, 88, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, K.; Myles, P.S.; Chan, M.T.V.; Paech, M.J.; Peyton, P.; Forbes, A.; McKenzie, D.; ENIGMA Trial Group. Risk Factors for Severe Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in a Randomized Trial of Nitrous Oxide-Based vs Nitrous Oxide-Free Anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2008, 101, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, D.; Radovanović, Z.; Škorić-Jokić, S.; Tatić, M.; Mandić, A.; Ivković-Kapicl, T. Thoracic Epidural Versus Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia after Open Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Acta Clin. Croat. 2017, 56, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakkuri, A.; Yli-Hankala, A.; Talja, P.; Mustola, S.; Tolvanen-Laakso, H.; Sampson, T.; Viertiö-Oja, H. Time-Frequency Balanced Spectral Entropy as a Measure of Anesthetic Drug Effect in Central Nervous System during Sevoflurane, Propofol, and Thiopental Anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2004, 48, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, S. Monitoring Consciousness: Using the Bispectral Index During Anesthesia, 2nd ed.; Aspect Medical Systems: Norwood, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald, M.; Ilies, C. Monitoring the Nociception-Anti-Nociception Balance. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2013, 27, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiku, M.; Uutela, K.; van Gils, M.; Korhonen, I.; Kymäläinen, M.; Meriläinen, P.; Paloheimo, M.; Rantanen, M.; Takala, P.; Viertiö-Oja, H.; et al. Assessment of Surgical Stress during General Anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2007, 98, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funcke, S.; Sauerlaender, S.; Pinnschmidt, H.O.; Saugel, B.; Bremer, K.; Reuter, D.A.; Nitzschke, R. Validation of Innovative Techniques for Monitoring Nociception during General Anesthesia: A Clinical Study Using Tetanic and Intracutaneous Electrical Stimulation. Anesthesiology 2017, 127, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; He, B.; Tong, X.; Xia, R.; Zhang, C.; Shi, X. Intraoperative Monitoring of Nociception for Opioid Administration: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019, 85, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.-D.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Song, N.; Meng, X.-W.; Liu, H.; Ji, F.-H.; Peng, K. Opioid-Free Anaesthesia Reduces Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting after Thoracoscopic Lung Resection: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 132, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorrilla-Vaca, A.; Healy, R.J.; Mirski, M.A. A Comparison of Regional Versus General Anesthesia for Lumbar Spine Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Studies. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2017, 29, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagistan, Y.; Okmen, K.; Dagistan, E.; Guler, A.; Ozkan, N. Lumbar Microdiscectomy Under Spinal and General Anesthesia: A Comparative Study. Turk. Neurosurg. 2015, 25, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, E.C.; Girardi, F.P.; Sama, A.; Pappou, I.P.; Urban, M.K.; Cammisa, F.P. Lumbar Microdiscectomy under Epidural Anesthesia: A Comparison Study. Spine J. Off. J. N. Am. Spine Soc. 2006, 6, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, R.; Kumar, N.; Sharma, J.P.; Kumar, R. Efficacy of Dexmedetomidine Added to Ropivacaine Infilteration on Postoperative Pain Following Spine Surgeries: A Randomized Controlled Study. Anesth. Essays Res. 2018, 12, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aveline, C.; Hetet, H.L.; Vautier, P.; Gautier, J.F.; Bonnet, F. Peroperative Ketamine and Morphine for Postoperative Pain Control after Lumbar Disk Surgery. Eur. J. Pain Lond. Engl. 2006, 10, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiowski, M.; Missir, A.; Pluta, A.; Szumera, I.; Stasiak, M.; Szopa, W.; Błaszczyk, B.; Możdżyński, B.; Majchrzak, K.; Tymowski, M.; et al. Influence of Infiltration Anaesthesia on Perioperative Outcomes Following Lumbar Discectomy under Surgical Pleth Index-Guided General Anaesthesia: A Preliminary Report from a Randomised Controlled Prospective Trial. Adv. Med. Sci. 2020, 65, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, A.; Stasiowski, M.J.; Lyssek-Boroń, A.; Król, S.; Krawczyk, L.; Niewiadomska, E.; Żak, J.; Kawka, M.; Dobrowolski, D.; Grabarek, B.O.; et al. Adverse Events during Vitrectomy under Adequacy of Anesthesia-An Additional Report. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, K.; Stasiowski, M.J.; Lyssek-Boroń, A.; Zmarzły, N. Adverse Events Following Vitreoretinal Surgeries Under Adequacy of Anesthesia with Combined Paracetamol/Metamizole—Additional Report. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiowski, M.J.; Pluta, A.; Lyssek-Boroń, A.; Król, S.; Krawczyk, L.; Niewiadomska, E.; Żak, J.; Kawka, M.; Dobrowolski, D.; Grabarek, B.O.; et al. Adverse Events during Vitreoretinal Surgery under Adequacy of Anesthesia Guidance-Risk Factor Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiowski, M.J.; Zmarzły, N.; Grabarek, B.O.; Gąsiorek, J. Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting Following Endoscopic Sinus Surgery under the Guidance of Adequacy of Anesthesia or Pupillometry with Intravenous Propofol/Remifentanil. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiowski, M.J.; Lyssek-Boroń, A.; Kawka-Osuch, M.; Niewiadomska, E.; Grabarek, B.O. Possibility of Using Surgical Pleth Index in Predicting Postoperative Pain in Patients after Vitrectomy Performed under General Anesthesia. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasiowski, M.J.; Marczak, K.; Lyssek-Boroń, A.; Zmarzły, N. Risk Factors for Intolerable Postoperative Pain After Vitreoretinal Surgery Under AoA-Guided General Anesthesia with Intravenous COX-3 Inhibitors: A Post Hoc Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laufenberg-Feldmann, R.; Müller, M.; Ferner, M.; Engelhard, K.; Kappis, B. Is “anxiety Sensitivity” Predictive of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting?: A Prospective Observational Study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 36, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazarika, R.; Parua, S.; Choudhury, D.; Barooah, R.K. Comparison of Bupivacaine Plus Magnesium Sulfate and Ropivacaine Plus Magnesium Sulfate Infiltration for Postoperative Analgesia in Patients Undergoing Lumbar Laminectomy: A Randomized Double-Blinded Study. Anesth. Essays Res. 2017, 11, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Palazón, J.; Tortosa Serrano, J.A.; Martínez-Pérez, M.; Piqueras-Pérez, C.; Burguillos López, S. Bupivacaine in continuous epidural infusion using a portable mechanical devise for postoperative analgesia after surgery for hernia of the lumbar disk. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. 2001, 48, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, C.; Ludwigs, J.; Gruenewald, M.; Thee, C.; Hanf, J.; Hanss, R.; Steinfath, M.; Bein, B. The Effect of Posture and Anaesthetic Technique on the Surgical Pleth Index. Anaesthesia 2012, 67, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzian, A.; Gholipour Baradari, A.; Alipour, A.; Emami Zeydi, A.; Zamani Kiasari, A.; Emadi, S.A.; Kheradmand, B.; Hadadi, K. Ultra-Low-Dose Naloxone as an Adjuvant to Patient Controlled Analgesia (PCA) With Morphine for Postoperative Pain Relief Following Lumber Discectomy: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2018, 30, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiołek, H.; Cettler, M.; Woroń, J.; Wordliczek, J.; Dobrogowski, J.; Mayzner-Zawadzka, E. The 2014 Guidelines for Post-Operative Pain Management. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2014, 46, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Pain Summit of the International Association for the Study Of Pain. Declaration of Montréal: Declaration That Access to Pain Management Is a Fundamental Human Right. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2011, 25, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluta, M.P.; Krzych, Ł.J. Usefulness of Apfel score to predict postoperative nausea and vomiting—Single-center experiences. Ann. Acad. Medicae Silesiensis 2018, 72, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvall, J.; Handscombe, M.; Maat, B.; So, K.; Suganthirakumar, A.; Leslie, K. Interpretation of the Four Risk Factors for Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in the Apfel Simplified Risk Score: An Analysis of Published Studies. Can. J. Anaesth. J. Can. Anesth. 2021, 68, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahovac, G.; Vilendecic, M.; Chudy, D.; Srdoc, D.; Skrlin, J. Nightmare Complication after Lumbar Disc Surgery: Cranial Nontraumatic Acute Epidural Hematoma. Spine 2011, 36, E1761–E1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekerak, R.; Mostafa, E.; Morris, M.T.; Nessim, A.; Vira, A.; Sharan, A. Comparative Outcome Analysis of Spinal Anesthesia versus General Anesthesia in Lumbar Fusion Surgery. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2021, 13, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmen, O.K.; Yentur, E.; Tunali, Y.; Balci, H.; Bahar, M. Does Preoperative Oral Carbohydrate Treatment Reduce the Postoperative Surgical Stress Response in Lumbar Disc Surgery? Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2017, 153, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozdemir, M.; Sert, H.; Yilmaz, N.; Kanbak, O.; Usta, B.; Demircioglu, R.I. Remifentanil-Propofol in Vertebral Disk Operations: Hemodynamics and Recovery versus Desflurane-n(2)o Inhalation Anesthesia. Adv. Ther. 2007, 24, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, S.; Min, K.; Marquardt, M.; Borgeat, A. Postoperative Intravenous Morphine Consumption, Pain Scores, and Side Effects with Perioperative Oral Controlled-Release Oxycodone after Lumbar Discectomy. Anesth. Analg. 2007, 105, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraçoğlu, A.; Eti, Z.; Konya, D.; Kabahasanoğlu, K.; Göğüş, F.Y. Perioperative Effects of Different Narcotic Analgesics Used to Improve Effectiveness of Total Intravenous Anaesthesia. Turk. J. Anaesthesiol. Reanim. 2016, 44, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersayli, D.T.; Gurbet, A.; Bekar, A.; Uckunkaya, N.; Bilgin, H. Effects of Perioperatively Administered Bupivacaine and Bupivacaine-Methylprednisolone on Pain after Lumbar Discectomy. Spine 2006, 31, 2221–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, M.R.; Asadian, M.A.; Imani, F.; Etezadi, F.; Moharari, R.S.; Amirjamshidi, A. General Anesthesia versus Combined Epidural/General Anesthesia for Elective Lumbar Spine Disc Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing the Impact of the Two Methods upon the Outcome Variables. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2013, 4, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, B.M.; Abraham, I.; Eberbach, N.; Kunst, G.; Stowe, D.F.; Martin, E. Differences in Cardiotoxicity of Bupivacaine and Ropivacaine Are the Result of Physicochemical and Stereoselective Properties. Anesthesiology 2002, 96, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdem, G.; Kavak Akelma, F.; Nalbant, B.; Gokbulut Ozaslan, N. Effect of Erector Spinae Plane Block on Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in Lumbar Disc Herniation Surgery. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2025, rapm-2025-106756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanapal, B.; Sistla, S.C.; Badhe, A.S.; Ali, S.M.; Ravichandran, N.T.; Galidevara, I. Effectiveness of Continuous Wound Infusion of Local Anesthetics after Abdominal Surgeries. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 212, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Gao, G.; Ma, R.; Lu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z. Bilateral Erector Spinae Plane Block by Multiple Injection for Pain Control in Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Surgery: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsterwald, M.; Muster, M.; Farshad, M.; Saporito, A.; Brada, M.; Aguirre, J.A. Spinal versus General Anesthesia for Lumbar Spine Surgery in High Risk Patients: Perioperative Hemodynamic Stability, Complications and Costs. J. Clin. Anesth. 2018, 46, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, L.; Yang, D.; Wang, T.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Ding, W. Cervical Plexus Anesthesia versus General Anesthesia for Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Medicine 2017, 96, e6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.H.; Saleem, H.; Ashfaq, A.D.; Malik, I.H.; Batool, F.; Siddique, K. General Anaesthesia Versus Regional Anaesthesia For Lumbar Laminectomy: A Review Of The Modern Literature. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad JAMC 2020, 32, 400–404. [Google Scholar]

- Jellish, W.S.; Thalji, Z.; Stevenson, K.; Shea, J. A Prospective Randomized Study Comparing Short- and Intermediate-Term Perioperative Outcome Variables after Spinal or General Anesthesia for Lumbar Disk and Laminectomy Surgery. Anesth. Analg. 1996, 83, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, M.A.; Taeimah, M. Evaluation of Thoracolumbar Interfascial Plane Block for Postoperative Analgesia after Herniated Lumbar Disc Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2018, 12, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, H.D.; Ludbrook, G.L.; Wing, A.; Sleigh, J.W. Intraoperative “Analgesia Nociception Index”-Guided Fentanyl Administration During Sevoflurane Anesthesia in Lumbar Discectomy and Laminectomy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesth. Analg. 2017, 125, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majer, D.; Stasiowski, M.J.; Lyssek-Boroń, A.; Krysik, K.; Zmarzły, N. Adequacy of Anesthesia Guidance Combined with Peribulbar Blocks Shows Potential Benefit in High-Risk PONV Patients Undergoing Vitreoretinal Surgeries. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reibaldi, M.; Fallico, M.; Longo, A.; Avitabile, T.; Astuto, M.; Murabito, P.; Minardi, C.; Bonfiglio, V.; Boscia, F.; Furino, C.; et al. Efficacy of Three Different Prophylactic Treatments for Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting after Vitrectomy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.Z.; Taguchi, A.; Holtmann, B.; Kurz, A. Effect of Supplemental Pre-Operative Fluid on Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anaesthesia 2003, 58, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewer, J.K.; Wong, M.J.; Bird, S.J.; Habib, A.S.; Parker, R.; George, R.B. Supplemental Perioperative Intravenous Crystalloids for Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD012212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.-C.; Hsu, W.-T.; Fu, C.-L.; Lai, Y.-W.; Shen, M.-L.; Chen, K.-B. Does Surgical Plethysmographic Index-Guided Analgesia Affect Opioid Requirement and Extubation Time? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Anesth. 2022, 36, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Dong, X.; Wu, C.; Guo, Z.; Wu, X. Intraoperative Pleth Variability Index-Based Fluid Management Therapy and Gastrointestinal Surgical Outcomes in Elderly Patients: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Perioper. Med. Lond. Engl. 2023, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiowski, M.J.; Starzewska, M.; Niewiadomska, E.; Król, S.; Marczak, K.; Żak, J.; Pluta, A.; Eszyk, J.; Grabarek, B.O.; Szumera, I.; et al. Adequacy of Anesthesia Guidance for Colonoscopy Procedures. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiowski, M.; Duława, A.; Szumera, I.; Marciniak, R.; Niewiadomska, E.; Kaspera, W.; Krawczyk, L.; Ładziński, P.; Grabarek, B.O.; Jałowiecki, P. Variations in Values of State, Response Entropy and Haemodynamic Parameters Associated with Development of Different Epileptiform Patterns during Volatile Induction of General Anaesthesia with Two Different Anaesthetic Regimens Using Sevoflurane in Comparison with Intravenous Induct: A Comparative Study. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enqvist, B.; Björklund, C.; Engman, M.; Jakobsson, J. Preoperative Hypnosis Reduces Postoperative Vomiting after Surgery of the Breasts. A Prospective, Randomized and Blinded Study. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 1997, 41, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Wang, Q. Perioperative Acupuncture Medicine: A Novel Concept Instead of Acupuncture Anesthesia. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.-E.; Oh, D.-S. Potential Benefits of Acupuncture for Enhanced Recovery in Gynaecological Surgery. Forsch. Komplementarmedizin 2015, 22, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, D.; Gardiner, J.; Harrison, R.; Kelly, A. Acupressure and the Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting after Laparoscopy. Br. J. Anaesth. 1999, 82, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiranvand, S.; Noparast, M.; Eslamizade, N.; Saeedikia, S. The Effects of Religion and Spirituality on Postoperative Pain, Hemodynamic Functioning and Anxiety after Cesarean Section. Acta Med. Iran. 2014, 52, 909–915. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkose, Z.; Ercan, B.; Unal, Y.; Yardim, S.; Kaymaz, M.; Dogulu, F.; Pasaoglu, A. Inhalation versus Total Intravenous Anesthesia for Lumbar Disc Herniation: Comparison of Hemodynamic Effects, Recovery Characteristics, and Cost. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2001, 13, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | Total | C Group | BF Group | RF Group | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 94 (100%) | n = 31 (33%) | n = 32 (34%) | n = 31 (33%) | |||

| Apfel X ± Sd Me (IQR) | pts | 1.39 ± 0.86 1(1) | 1.52 ± 0.89 1(1) | 1.34 ± 0.83 1(1) | 1.32 ± 0.87 1(1) | 0.7 NS |

| % | 29.48 ± 14.86 21(18) | 31.6 ± 16.1 21(18) | 28.5 ± 13.8 21(18) | 28.3 ± 14.9 21(18) | 0.7 NS | |

| NPRS X ± Sd Me (IQR) | min | 1.9 ± 1.57 2(3) | 2.48 ± 1.77 2(1) | 1.44 ± 1.41 2(3) | 1.81 ± 1.38 2(3) | 0.1 NS |

| max | 4.17 ± 3.08 3.5(5) | 5.55 ± 3.04 6(5) | 3.72 ± 3.26 3.5(7) | 3.26 ± 2.48 3(2) | C vs. BF, p = 0.047; C vs. RF, p = 0.01 | |

| Moderate-to-severe pain NPRS > 3 n (%) | no | 48 (51.07%) | 10 (32.3%) | 17 (53.1%) | 21 (67.7%) | C vs. RF, p = 0.03 |

| yes | 46 (48.93%) | 21 (67.7%) | 15 (46.9%) | 10 (32.3%) | ||

| Motion sickness n (%) | no | 93 (98.9%) | 31 (100%) | 31 (96.9%) | 31 (100%) | - |

| yes | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Smoking n (%) | no | 51 (54.3%) | 16 (51.6%) | 14 (43.8%) | 21 (67.7%) | 0.2 NS |

| yes | 43 (45.7%) | 15 (48.4%) | 18 (56.2%) | 10 (32.3%) | ||

| Postoperative use of opioid drugs n (%) | no | 55 (58.5%) | 12 (38.7%) | 19 (59.4%) | 24 (77.4%) | C vs. RF, p = 0.005 |

| yes | 39 (41.5%) | 19 (61.3%) | 13 (40.6%) | 7 (22.6%) | ||

| Postoperative MF consumption in the PACU X ± Sd Me (IQR) | mg | 4.6 ± 5.66 0(10) | 7.1 ± 5.93 8(12) | 4 ± 4.93 0(10) | 2.71 ± 5.33 0(0) | C vs. RF, p = 0.009 |

| Intraoperative FNT requirement X ± Sd Me (IQR) | µg | 511.17 ± 388 400(450) | 491.94 ± 244.64 500(400) | 623.44 ± 548.01 500(525) | 414.52 ± 270.24 350(400) | 0.2 NS |

| Intraoperative Data | Total | C Group | BF Group | RF Group | p-Value | ||

| N = 94 (100%) | n = 31 (33%) | n = 32 (34%) | n = 31 (33%) | ||||

| Overall PONV n (%) | yes | 12 (12.8%) | 3 (9.7%) | 5 (15.6%) | 4 (12.9%) | 0.9 NS | |

| Early PONV n (%) | yes | 7 (7.4%) | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (3.1%) | 4 (12.9%) | 0.3 NS | |

| Late PONV n (%) | yes | 9 (9.6%) | 2 (6.5%) | 5 (15.6%) | 2 (6.5%) | 0.5 NS | |

| Both early and late PONV n (%) | yes | 4 (4.6%) | 1 (3.2%) | 1 (3.1%) | 2 6.5%) | 0.8 NS | |

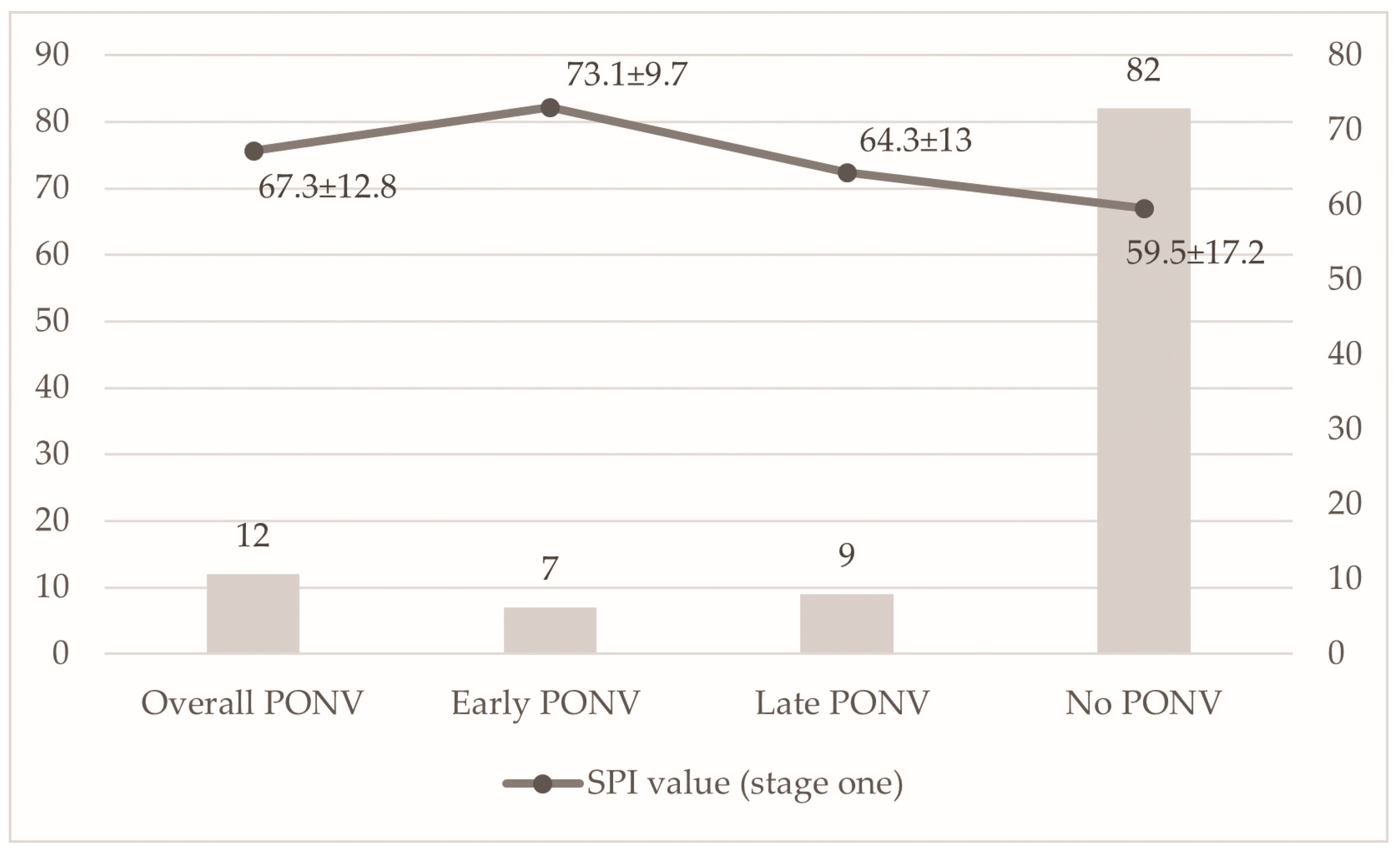

| Apfel Score [Point] n (%) | Low risk of PONV | Medium risk of PONV | High risk of PONV | p-Value | First monitored SPI value (stage one) | ||

| 0 (10% Risk of PONV) n = 13 | 1 (21% Risk of PONV) n = 41 | 2 (39% Risk of PONV) n = 30 | 3 (61% Risk of PONV) n = 10 | ||||

| Overall PONV n = 12 | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.9%) | 5 (16.7%) | 5 (50%) | 0 vs. 3, p = 0.045; 1 vs. 3, p = 0.01 | 67.3 ± 12.8 70(18.5) | |

| No PONV n = 82 | 13 (100%) | 39 (95.1%) | 25 (83.3%) | 5 (50%) | 59.5 ± 17.2 62(29) | ||

| Early PONV n = 7 | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | 3 (42.9%) | 1 vs. 3, p = 0.02 | 73.1 ± 9.7 74(20) | |

| Late PONV n = 9 | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0 vs. 3, p = 0.03; 1 vs. 3, p = 0.004 | 64.3 ± 13 62(18) | |

| p-value | - | - | - | - | - | Early PONV vs. No PONV, p = 0.03 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stasiowski, M.J.; Ćmiel-Smorzyk, K.; Zmarzły, N. Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting After Open Lumbar Discectomy: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial Using Adequacy of Anesthesia Monitoring. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010360

Stasiowski MJ, Ćmiel-Smorzyk K, Zmarzły N. Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting After Open Lumbar Discectomy: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial Using Adequacy of Anesthesia Monitoring. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):360. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010360

Chicago/Turabian StyleStasiowski, Michał J., Karolina Ćmiel-Smorzyk, and Nikola Zmarzły. 2026. "Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting After Open Lumbar Discectomy: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial Using Adequacy of Anesthesia Monitoring" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010360

APA StyleStasiowski, M. J., Ćmiel-Smorzyk, K., & Zmarzły, N. (2026). Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting After Open Lumbar Discectomy: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial Using Adequacy of Anesthesia Monitoring. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010360