Examining the Unanswered Questions in TSW: A Case Series of 16 Patients and Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Case Study

3.2. Cohort Characteristics

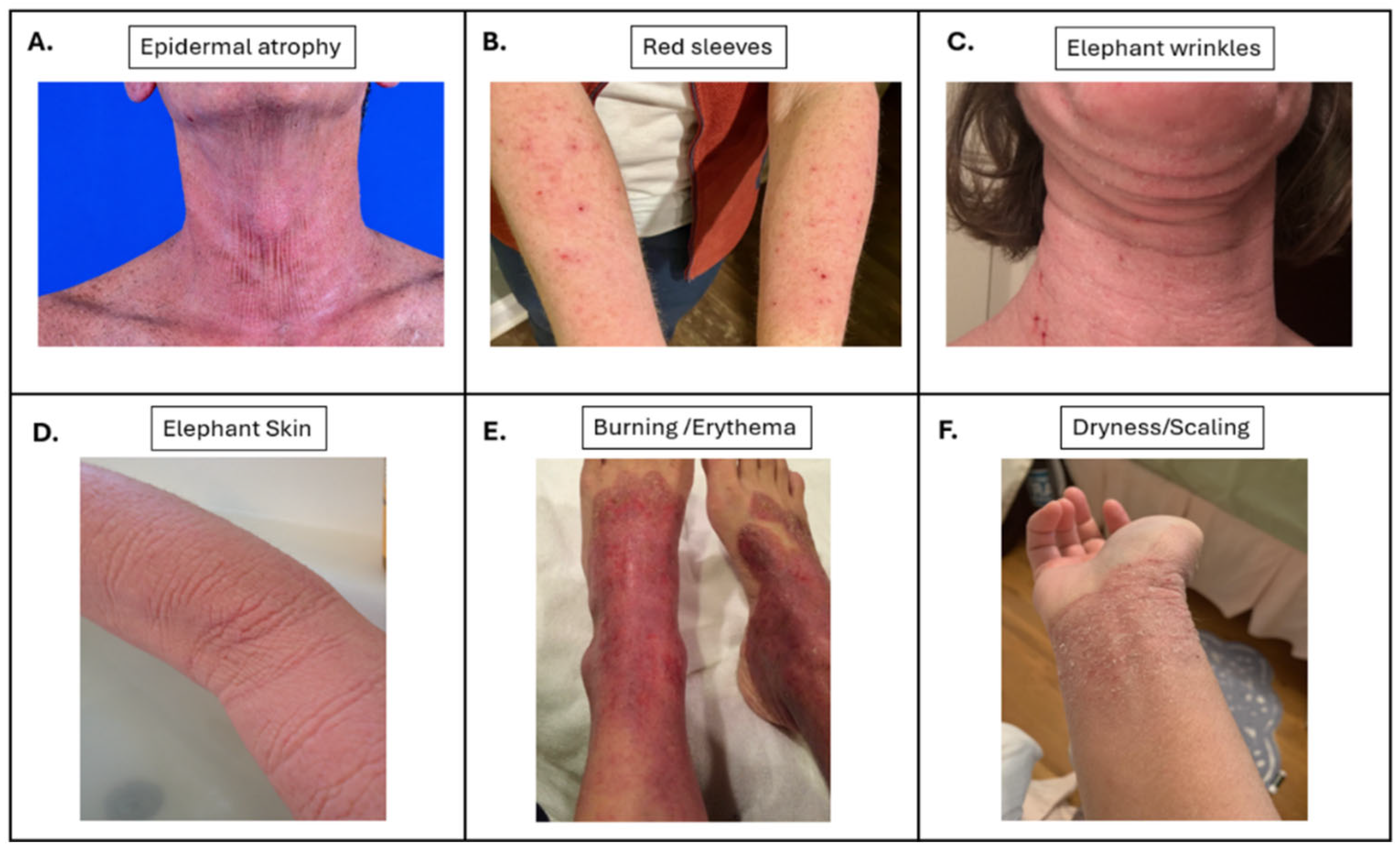

3.3. Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

3.4. Treatment Approaches

3.5. Follow-Up Survey

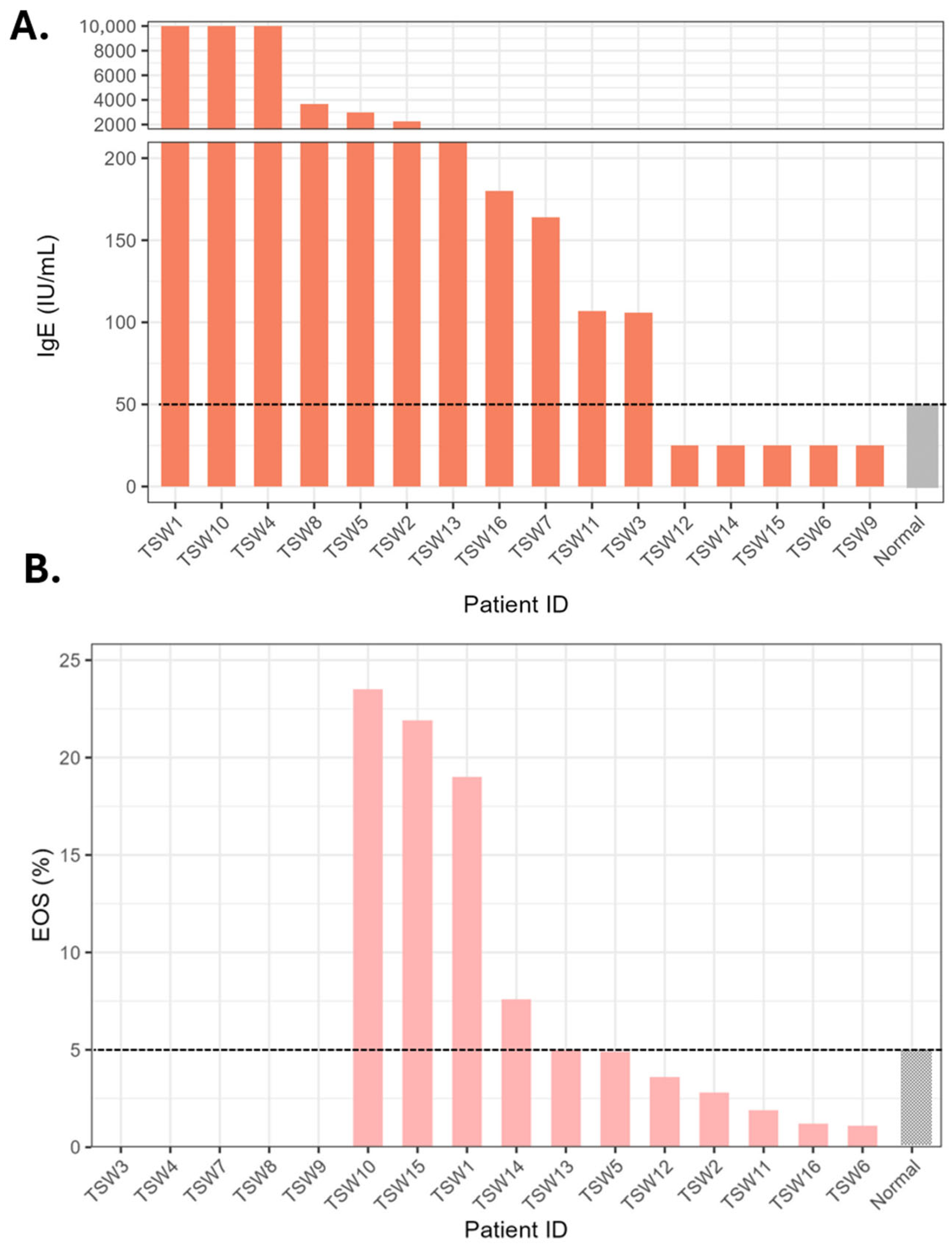

3.6. Laboratory Findings

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Atopic Dermatitis |

| DLQI | Dermatology Life Quality Index |

| HFSC | Human Follicular Stem Cells |

| TSW | Topical Steroid Withdrawal |

References

- Stacey, S.K.; McEleney, M. Topical Corticosteroids: Choice and Application. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 103, 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, H.F.; Leung, D.Y.M.; Lack, G.; Sindher, S.; Ciaccio, C.E.; Chan, S.; Nadeau, K.C.; Brough, H.A. Topical steroid withdrawal and atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 132, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, R.; Proctor, A.; Moss, C. Topical steroid withdrawal: A survey of UK dermatologists’ attitudes. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 49, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guckian, J.; Hughes, O.; Nikookam, Y.; Nair, R.; Asif, A.; Brown, J.; Bewley, A.; Latheef, F. Topical steroid withdrawal: Self-diagnosis, unconscious bias and social media. Ski. Health Dis. 2025, 5, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroman, F.; Schimmel, C.S.; van der Rijst, L.P.; de Graaf, M.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Kemperman, P.M.J.H.; Hijnen, D.J.; Haeck, I.M. Topical Steroid Withdrawal: Perspectives of Dutch Healthcare Professionals. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2025, 105, adv44209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.; Bell, F.; Ross, G. Topical Steroid Withdrawal: A Perspective of Australian Dermatologists. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2025, 66, e433–e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, N.; Rogers, M.; Stein, A.; Thompson Coon, J.; Stein, K. Reviewing the Evidence Base for Topical Steroid Withdrawal Syndrome in the Research Literature and Social Media Platforms: An Evidence Gap Map. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e57687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajar, T.; Leshem, Y.A.; Hanifin, J.M.; Nedorost, S.T.; Lio, P.A.; Paller, A.S.; Block, J.; Simpson, E.L. A systematic review of topical corticosteroid withdrawal (“steroid addiction”) in patients with atopic dermatitis and other dermatoses. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 541–549.e542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Lio, P.A. Topical corticosteroid withdrawal (‘steroid addiction’): An update of a systematic review. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheary, B. Topical corticosteroid addiction and withdrawal—An overview for GPs. Aust. Fam. Physician 2016, 45, 386–388. [Google Scholar]

- Fukaya, M.; Sato, K.; Sato, M.; Kimata, H.; Fujisawa, S.; Dozono, H.; Yoshizawa, J.; Minaguchi, S. Topical steroid addiction in atopic dermatitis. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2014, 6, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheary, B. Steroid Withdrawal Effects Following Long-term Topical Corticosteroid Use. Dermatitis 2018, 29, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobnam, N.; Ratley, G.; Saksena, S.; Yadav, M.; Chaudhary, P.P.; Sun, A.A.; Howe, K.N.; Gadkari, M.; Franco, L.M.; Ganesan, S.; et al. Topical Steroid Withdrawal Is a Targetable Excess of Mitochondrial NAD. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 145, 1953–1968.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboobacker, S.; Harris, B.W.; Limaiem, F. Lichenification. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Orlando, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bieber, T. How to Define Atopic Dermatitis? Dermatol. Clin. 2017, 35, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.B.; Bandhauer, M.E.; Bunker, A.M.; Roberts, W.L.; Hill, H.R. New childhood and adult reference intervals for total IgE. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y. Comparative analysis of dibutyric cAMP and butyric acid on the differentiation of human eosinophilic leukemia EoL-1 cells. Immune Netw. 2015, 15, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Rothenberg, M.E. Roles and regulation of gastrointestinal eosinophils in immunity and disease. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, T.S.-r.; Barlow, R.; Mohandas, P.; Bewley, A. Topical steroid withdrawal: An emerging clinical problem. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 48, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.Y.; Chandran, N.S.; Choi, E.C. Steroid Phobia: Is There a Basis? A Review of Topical Steroid Safety, Addiction and Withdrawal. Clin. Drug Investig. 2021, 41, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.P.; Kong, J.S.; Teuber, S.S. Reply to “Severe topical corticosteroid withdrawal syndrome or enigmatic drug eruption?”. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 1126–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, M.; Grinich, E.; Simpson, E. Topical steroid withdrawal treated with ruxolitinib cream. JAAD Case Rep. 2024, 48, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, K.; Lio, P. Pediatric Topical Steroid Withdrawal Syndrome: What Is Known, What Is Unknown. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2025, 42, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.P.; Kong, J.S.; Teuber, S.S. Severe Topical Corticosteroid Withdrawal Syndrome from Over-the-Counter Steroids. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 4147–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheary, B. Topical corticosteroid addiction and withdrawal in a 6 year old. J. Prim. Health Care 2017, 9, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsterholm, M.; af Klinteberg, M.; Vrang, S.; Sigurdardottir, G.; Sandström Falk, M.; Shayesteh, A. Topical Steroid Withdrawal in Atopic Dermatitis: Patient-reported Characterization from a Swedish Social Media Questionnaire. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2025, 105, adv40187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, F.; Abou Shahla, W.; Saade, D. Investigating Topical Steroid Withdrawal Videos on TikTok: Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Top 100 Videos. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e48389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheary, B. Topical Steroid Withdrawal: A Case Series of 10 Children. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2019, 99, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász, M.L.W.; Curley, R.A.; Rasmussen, A.; Malakouti, M.; Silverberg, N.; Jacob, S.E. Systematic Review of the Topical Steroid Addiction and Topical Steroid Withdrawal Phenomenon in Children Diagnosed with Atopic Dermatitis and Treated with Topical Corticosteroids. J. Dermatol. Nurses’ Assoc. 2017, 9, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, A.; Osaka, T.; Fukuya, Y.; Yanagisawa, N.; Ishiguro, N. Comparative Analysis of the Skin Microbiota of Rosacea, Steroid-Induced Rosacea and Perioral Dermatitis. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 34, e70084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijendra, A.; Shobnam, N.; Jordan, J.; Thota, P.; Myles, I.A. Biomarkers Are Consistent With Patient-Reported Allergic Sensitization in Topical Steroid Withdrawal. Allergy 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskey, A.R.; Kopulos, D.; Kwan, M.; Reyes, N.; Figueroa, C.; Mo, X.; Yang, N.; Tiwari, R.; Geliebter, J.; Li, X.M. Berberine Inhibits the Inflammatory Response Induced by Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Atopic Eczema Patients via the TNF-alpha/Inflammation/RAGE Pathways. Cells 2024, 13, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, K.; Yang, N.; Uzun, S.; Thanik, E.; Ehrlich, P.; Chung, D.; Yuan, Q.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Li, X.-M. Effect of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in moderate-to-severe eczema in clinic and animal model: Beyond corticosteroids. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, AB198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; Rose-Ward, S.; Osei-Karikari, K.; Myles, I.A. Possible Treatment of Topical Steroid Withdrawal with Methylene Blue Case Report: Implications for Mitochondrial Pathology. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2025, 17, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, K.A.; Treister, A.D.; Lio, P.A. Dupilumab in the management of topical corticosteroid withdrawal in atopic dermatitis: A retrospective case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2018, 4, 860–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunoki, M.; Fukuchi, K.; Fujiyama, T.; Ito, T.; Honda, T. Resolution of Molluscum Contagiosum After Discontinuation of Topical Corticosteroids During Dupilumab Therapy for Atopic Dermatitis: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e67391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, R.B.; Griffiths, C.E.M. Systemic therapies for psoriasis: Methotrexate, retinoids, and cyclosporine. Clin. Dermatol. 2008, 26, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallen-Russell, C.; Gijsberts-Veens, A.; Wallen-Russell, S. Could Modifying the Skin Microbiome, Diet, and Lifestyle Help with the Adverse Skin Effects after Stopping Long-Term Topical Steroid Use? Allergies 2022, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feschuk, A.M.; Pratt, M.E. Topical steroid withdrawal syndrome in a mother and son: A case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2023, 11, 2050313X231164268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Phan, P.; Law, J.Y.; Choi, E.; Chandran, N.S. Qualitative analysis of topical corticosteroid concerns, topical steroid addiction and withdrawal in dermatological patients. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Topical Steroid Awareness Network (ITSAN). ITSAN Topical Steroid Withdrawal Syndrome Support Group-Private Group. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ITSANSupport/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

| Age | Gender | Race | Prior History of AD | Exposure Time | Time Since Discontinuation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 27 | F | Asian | Yes | 2 years, 2 months | 1 year, 7 months |

| Case 2 | 50 | F | White | Yes | 26 years | 11 years |

| Case 3 | 51 | F | White | No | 20 years | 7 years |

| Case 4 | 36 | F | Asian | Yes | 27 years | 4 years, 3 months |

| Case 5 | 38 | F | White | Yes | 29–30 years | 3 years, 2 months |

| Case 6 | 58 | M | White | No | 5 years, 9 months | 3 years, 3 months |

| Case 7 | 21 | M | White | Yes | 16 years | 6 months |

| Case 8 | 27 | F | Asian | Yes | “On/off for many years” | 8 months |

| Case 9 | 34 | F | White | Yes | “On/off for 21 years” | 8 years, 6 months |

| Case 10 | 40 | F | Black | Yes | 20 years | 4 months |

| Case 11 | 46 | F | White | Yes | 2–3 years | 10 years |

| Case 12 | 35 | F | White | Yes | “20+ years” | More than 6 months |

| Case 13 | 33 | F | Asian | Yes | 12 years, 8 months | 1 year, 8 months |

| Case 14 | 29 | F | White | Yes | 16 years | 19 months since last oral, 24 months since last topical |

| Case 15 | 41 | F | White | Yes | 30 years (17 consecutive) | 7 years, 8 months |

| Case 16 | 28 | F | White | Yes | 23 years | 14 months |

| Symptom | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Burning | 16 (100) |

| Heat/sun sensitivity | 16 (100) |

| Itch | 16 (100) |

| Pain | 16 (100) |

| Shedding | 16 (100) |

| Erythema | 16 (100) |

| Dryness | 16 (100) |

| Scaling | 16 (100) |

| Elephant skin | 15 (94) |

| Swelling/edema | 15 (94) |

| Thermodysregulation | 14 (88) |

| Nerve symptoms (zingers) | 14 (88) |

| Oozing | 13 (84) |

| Metal smell | 9 (56) |

| Hair loss | 9 (56) |

| New allergies | 8 (50) |

| Swollen lymph nodes | 8 (50) |

| Insomnia | 7 (44) |

| Joint pain | 7 (44) |

| Palpitations | 6 (38) |

| Unusual smell | 5 (31) |

| Vision changes | 4 (25) |

| Papules | 1 (6) |

| Pustules | 1 (6) |

| Skin tightness | 0 |

| Telangiectasia | 0 |

| Domain | Response Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Daily itch duration | Less than 6 h/day | 3 (38%) |

| 6–12 h/day | 3 (38%) | |

| 12–18 h/day | 2 (25%) | |

| Itch intensity | Mild | 4 (50%) |

| Moderate | 3 (38%) | |

| Severe | 1 (13%) | |

| Change since prior month to survey administration | Much better but still present | 2 (25%) |

| A little better but still present | 3 (38%) | |

| Unchanged | 3 (38%) | |

| Impact on sleep | Never or not applicable | 4 (50%) |

| Rarely affects | ||

| Delays falling asleep and causes awakenings | 3 (38%) | |

| Occasionally delays falling asleep | 1 (13%) | |

| Impact on leisure/social activities | Never or not applicable | 3 (38%) |

| Rarely affects | 2 (25%) | |

| Occasionally affects | 2 (25%) | |

| Always affects | 1 (13%) | |

| Impact on household/errands | Never or not applicable | 4 (50%) |

| Rarely affects | 1 (13%) | |

| Occasionally affects | 2 (25%) | |

| Always affects | 1 (13%) | |

| Impact on work/school | Never or not applicable | 5 (63%) |

| Rarely affects | 0 (0%) | |

| Occasionally affects | 2 (25%) | |

| Always affects | 1 (13%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lu, M.Y.; Erickson, A.; Vijendra, A.; Ratley, G.; Sun, A.A.; Myles, I.A.; Shobnam, N. Examining the Unanswered Questions in TSW: A Case Series of 16 Patients and Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010361

Lu MY, Erickson A, Vijendra A, Ratley G, Sun AA, Myles IA, Shobnam N. Examining the Unanswered Questions in TSW: A Case Series of 16 Patients and Review of the Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010361

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Max Y., Anna Erickson, Aditi Vijendra, Grace Ratley, Ashleigh A. Sun, Ian A. Myles, and Nadia Shobnam. 2026. "Examining the Unanswered Questions in TSW: A Case Series of 16 Patients and Review of the Literature" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010361

APA StyleLu, M. Y., Erickson, A., Vijendra, A., Ratley, G., Sun, A. A., Myles, I. A., & Shobnam, N. (2026). Examining the Unanswered Questions in TSW: A Case Series of 16 Patients and Review of the Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010361