Minimally Invasive Aortic Valve Replacement in Elderly Patients: Insights from a Large Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Ethical Statement

2.3. Surgical Technique

2.4. Follow-Up and Patient Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Postoperative Morbidity

3.3. Intrahospital Mortality

3.4. Early (30-Day) Mortality

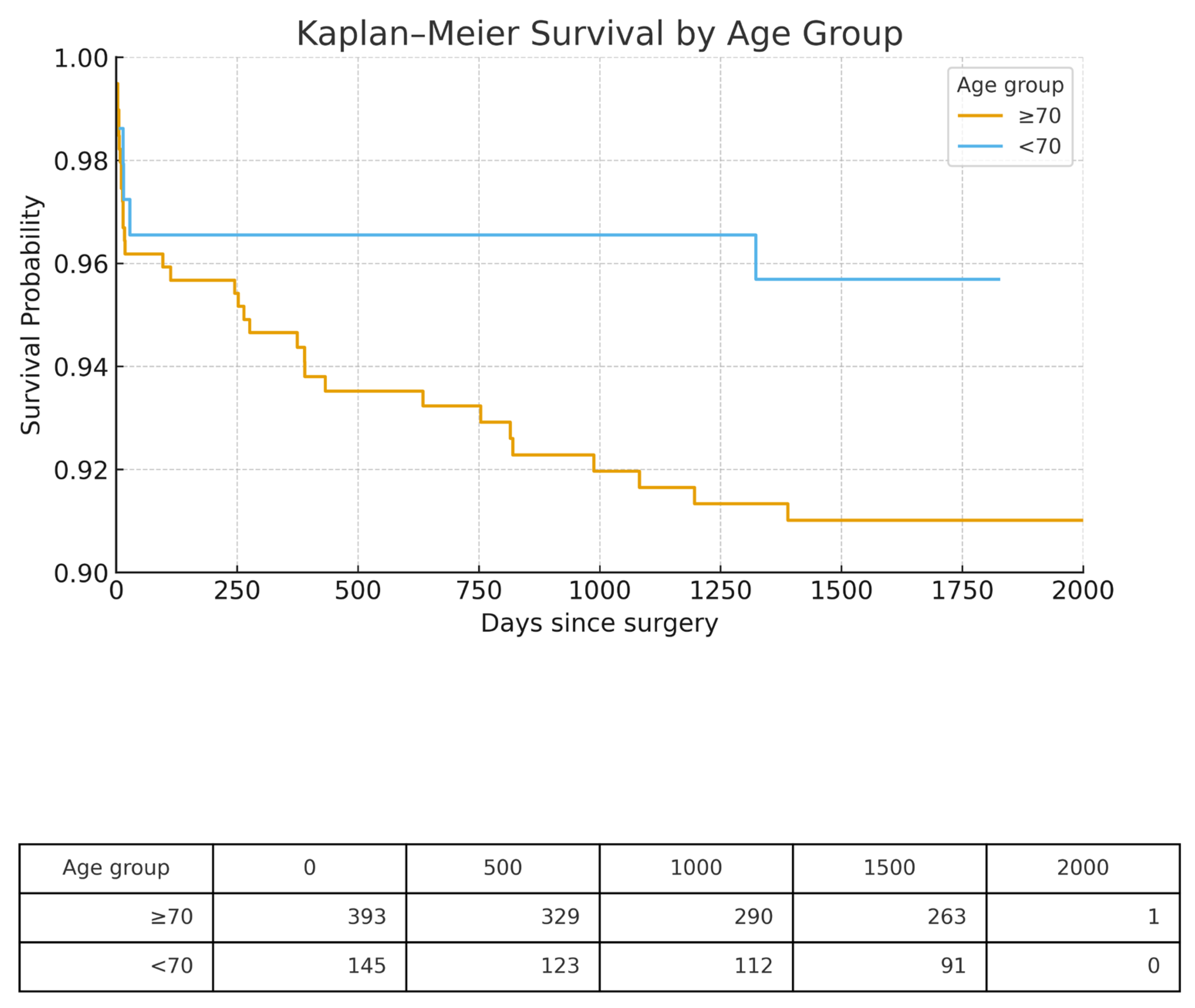

3.5. Long-Term Survival

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

4.2. Postoperative Bleeding

4.3. Permanent Pacemaker Implantation

4.4. Postoperative Sepsis

4.5. Stroke and Renal Failure

4.6. Key Clinical Message

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Andari, R.; Fialka, N.M.; Shan, S.; White, A.; Manikala, V.K.; Wang, S. Aortic Valve Replacement: Is Minimally Invasive Really Better? A Contemporary Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiol. Rev. 2024, 32, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Praet, K.M.; Nersesian, G.; Kukucka, M.; Kofler, M.; Wert, L.; Klein, C.; Unbehaun, A.; Kempfert, J.; Falk, V. Minimally invasive surgical aortic valve replacement via a partial upper ministernotomy. Multimedia Man. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamelas, J.; Alnajar, A. Recent advances in devices for minimally invasive aortic valve replacement. Expert. Rev. Med. Devices 2020, 17, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praz, F.; Borger, M.A.; Lanz, J.; Marin-Cuartas, M.; Abreu, A.; Adamo, M.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; Barili, F.; Bonaros, N.; Cosyns, B.; et al. 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur. Hear. J. 2025, 46, 4635–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, C.; Adams, H. Aortic stenosis and transcatheter aortic valve implantation in the elderly. Aust. J. Gen. Pr. 2023, 52, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatas, C.; Afilalo, J. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement over age 90: Risks vs. benefits. Clin. Cardiol. 2020, 43, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, A.; Hage, F.; Al-Amodi, H.; Gupta, S.; Papatheodorou, S.I.; Hawkins, R.; Ailawadi, G.; Mittleman, M.A.; Chu, M.W.A. Minimally Invasive Versus Sternotomy for Mitral Surgery in the Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Innovations 2021, 16, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, M.; Hussain, A.; Akowuah, E. Minimally invasive surgical aortic valve replacement. Heart 2019, 105, s10–s15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, J.; Zainulabdin, O.; Marzouk, M.; Guay, S.; Vasse, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Dagenais, F.; Caus, T.; Voisine, P. Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in the Elderly: It Is Worth It! Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 34, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francica, A.; Barbero, C.; Tonelli, F.; Cerillo, A.G.; Lodo, V.; Centofanti, P.; Marchetto, G.; Di Credico, G.; De Paulis, R.; Stefano, P.; et al. Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery in Elderly Patients: Results from a Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocchieri, R.; Mousavi, I.; Verbeek, E.C.; Riezebos, R.K.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.P.; de Mol, B. Elderly patients benefit from minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: Perioperative risk management matters. Interdiscip. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2024, 38, ivad211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisatomi, K.; Miura, T.; Obase, K.; Matsumaru, I.; Nakaji, S.; Tanigawa, A.; Taguchi, S.; Takura, M.; Nakao, Y.; Eishi, K. Minimally Invasive Valvular Surgery in the Elderly—Safety, Early Recovery, and Long-Term Outcomes. Circ. J. 2022, 86, 1725–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhassan, H.; Abdelbar, A.; Taylor, R.; Laskawski, G.; Saravanan, P.; Knowles, A.; Zacharias, J. A Propensity Score Analysis of Early and Long-Term Outcomes of Retrograde Arterial Perfusion for Endoscopic and Minimally Invasive Heart Valve Surgery in Both Young and Elderly Patients. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabata, M.; Khalpey, Z.; Shekar, P.S.; Cohn, L.H. Reoperative minimal access aortic valve surgery: Minimal mediastinal dissection and minimal injury risk. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008, 136, 1564–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElBardissi, A.W.; Shekar, P.; Couper, G.S.; Cohn, L.H. Minimally invasive aortic valve replacement in octogenarian, high-risk, transcatheter aortic valve implantation candidates. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 141, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faerber, G.; Berretta, P.; Nguyen, T.C.; Wilbring, M.; Lamelas, J.; Stefano, P.; Kempfert, J.; Rinaldi, M.; Pacini, D.; Pitsis, A.; et al. Pacemaker implantation after concomitant tricuspid valve repair in patients undergoing minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: Results from the Mini-Mitral International Registry. JTCVS Open 2024, 17, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, R.T.; Lugg, D.; Gray, R.; Hollis, D.; Stoner, M.; Williams, J.L. Pacemaker implantation in the extreme elderly. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2012, 33, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujak-Rogala, E.; Lisiak, M.H.; Uchmanowicz, I. Quality of life and frailty: An important issue for elderly patients with an implanted pacemaker. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2022, 21, zvac060.121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, A.; Del Castillo Carnevali, H.; Torres Lopez, M.; Goncalves Sánchez, F.; Dejuan Bitriá, C.; Rubio Alonso, M.; Duarte Torres, J.; Biscotti Rodil, B.; Álvarez Antón, S.; Martí Sánchez, D. Leadless pacemaker for urgent permanent implantation in elderly and very elderly patients. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, e27–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, E.A.; Galloway, A.C.; Ribakove, G.H.; Buttenheim, P.M.; Esposito, R.; Baumann, F.G.; Colvin, S.B. Minimally invasive port access surgery reduces operative morbidity for valve replacement in the elderly. Heart Surg. Forum 1999, 2, 212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, J.; Naito, S.; Neumann, N.; Conradi, L.; Reichenspurner, H.; Girdauskas, E. Impact of Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery in Elderly Patients. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 66, S1–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, G.M.; Levy, E.M.; Hammermeister, K.E.; Grover, F.; Daley, J. Independent association between acute renal failure and mortality following cardiac surgery. Am. J. Med. 1998, 104, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.; De Manna, N.D.; Schulz, S.; Ius, F.; Haverich, A.; Cebotari, S.; Tudorache, I.; Salman, J. Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery in the Elderly. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2024, 72, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, J.R.; Henry, M.; Rahouma, M.; Khan, F.M.; Wingo, M.; Hameed, I.; Di Franco, A.; Guy, T.S.; Girardi, L.N.; Gaudino, M. Systematic preoperative CT scan is associated with reduced risk of stroke in minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 278, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | <70 Years | ≥70 Years | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.4 ± 10.7 | 83.6 ± 3.2 | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 291/729 (39.9%) | 134/261 (51.3%) | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 ± 6.3 | 26.2 ± 4.6 | 0.004 |

| COPD | 89/729 (12.2%) | 41/261 (15.7%) | 0.151 |

| Renal impairment | 125/729 (17.1%) | 85/261 (32.6%) | <0.001 |

| On dialysis pre-op | 14/729 (1.9%) | 9/261 (3.4%) | 0.160 |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | 217/729 (29.8%) | 118/261 (45.2%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (any) | 174/729 (23.9%) | 61/261 (23.4%) | 0.871 |

| NYHA III–IV | 118/666 (17.7%) | 68/257 (26.5%) | <0.001 |

| Complication | <70 Years | >70 Years | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECMO/right heart failure | 4/729 (0.5%) | 2/261 (0.8%) | 0.698 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 14.9 ± 6.5 | 16.4 ± 11.6 | 0.605 |

| ICU stay (days) | 2.2 ± 3.4 | 2.7 ± 3.8 | 0.04 |

| Major bleeding | 30/729 (4.1%) | 20/261 (7.7%) | 0.025 |

| New pacemaker | 42/729 (5.8%) | 26/261 (10.0%) | 0.021 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1/729 (0.1%) | 1/261 (0.4%) | 0.448 |

| Dialysis | 13/729 (1.8%) | 8/261 (3.1%) | 0.217 |

| Re-thoracotomy | 22/729 (3.0%) | 9/261 (3.4%) | 0.732 |

| Sepsis | 8/729 (1.1%) | 9/261 (3.4%) | 0.012 |

| Stroke | 13/729 (1.8%) | 3/261 (1.1%) | 0.486 |

| Covariate (Row Order) | Log HR | HR (95% CI) | p | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 70 years | 0.909 | 2.48 (1.33–4.64) | 0.004 | The elderly cohort has ~2.5-fold higher long-term mortality vs. those <70 years, independent of other factors. |

| Male sex | −0.257 | 0.77 (0.42–1.43) | 0.411 | Sex is not a significant predictor after adjustment. |

| COPD | 0.785 | 2.19 (1.09–4.42) | 0.028 | COPD roughly doubles the risk of death. |

| Renal impairment | 0.631 | 1.88 (0.96–3.69) | 0.066 | Trend toward higher risk, but not quite significant at 0.05. |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | −0.081 | 0.92 (0.47–1.80) | 0.813 | No evident association with late mortality. |

| Variable | OR | 95% CI L | 95% CI U | p > |z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 70 years | 2.377842 | 1.024619 | 5.518277 | 0.043739 |

| Male sex | 1.173534 | 0.506475 | 2.71915 | 0.70897 |

| COPD | 1.733351 | 0.648504 | 4.632979 | 0.272827 |

| Renal impairment | 1.9436 | 0.793203 | 4.762438 | 0.146139 |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | 0.995601 | 0.409587 | 2.420054 | 0.992239 |

| Covariate | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 70 years | 2.48 | 1.33–4.64 | 0.004 |

| COPD | 2.19 | 1.09–4.42 | 0.028 |

| Renal impairment | 1.88 | 0.96–3.69 | 0.066 |

| Male sex | 0.77 | 0.42–1.43 | 0.411 |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | 0.92 | 0.47–1.80 | 0.813 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Amanov, L.; Arjomandi Rad, A.; Ali-Hasan-Al-Saegh, S.; Jauken, A.A.; Zotos, P.-A.; Athanasiou, T.; Ruemke, S.; Karsten, J.; Salman, J.; Ius, F.; et al. Minimally Invasive Aortic Valve Replacement in Elderly Patients: Insights from a Large Cohort. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010354

Amanov L, Arjomandi Rad A, Ali-Hasan-Al-Saegh S, Jauken AA, Zotos P-A, Athanasiou T, Ruemke S, Karsten J, Salman J, Ius F, et al. Minimally Invasive Aortic Valve Replacement in Elderly Patients: Insights from a Large Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010354

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmanov, Lukman, Arian Arjomandi Rad, Sadeq Ali-Hasan-Al-Saegh, Antonia Annegret Jauken, Prokopis-Andreas Zotos, Thanos Athanasiou, Stefan Ruemke, Jan Karsten, Jawad Salman, Fabio Ius, and et al. 2026. "Minimally Invasive Aortic Valve Replacement in Elderly Patients: Insights from a Large Cohort" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010354

APA StyleAmanov, L., Arjomandi Rad, A., Ali-Hasan-Al-Saegh, S., Jauken, A. A., Zotos, P.-A., Athanasiou, T., Ruemke, S., Karsten, J., Salman, J., Ius, F., Deniz, E., Schmack, B., Ruhparwar, A., Zubarevich, A., & Weymann, A. (2026). Minimally Invasive Aortic Valve Replacement in Elderly Patients: Insights from a Large Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010354