The Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy on Non-Tumorous Barrett’s Dysplasia of the Esophagus: A Multicenter Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology and Clinical Significance

1.2. Diagnosis and Risk Stratification

1.3. Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Management

1.4. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy (NCRT)

1.5. Rationale and Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Cohort

3.2. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.3. Treatment Characteristics

3.4. Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Previous Literature

4.2. Clinical Implications

4.3. Biological Considerations and Mechanistic Insights

4.4. Challenges and the Role of Preoperative Planning

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Summary and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BE | Barrett’s esophagus |

| EAC | Esophageal adenocarcinoma |

| NCRT | Neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy |

| HGD | High-grade dysplasia |

| LGD | Low-grade dysplasia |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| 5-FU | 5-Fluorouracil |

| CROSS | Chemoradiotherapy for Oesophageal cancer followed by Surgery Study |

| ESOPEC | Esophageal cancer trial |

References

- Pohl, H.; Welch, H.G. The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrift, A.P. Global burden and epidemiology of Barrett oesophagus and oesophageal cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Lin, J.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Huang, K.; Lin, D.; Xiao, Y.; Li, C.; Zeng, D. Esophageal cancer trends in the US from 1992 to 2019 with projections to 2044 using SEER data. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codipilly, D.C.; Sawas, T.; Dhaliwal, L.; Johnson, M.L.; Lansing, R.; Wang, K.K.; Leggett, C.L.; Katzka, D.A.; Iyer, P.G. Epidemiology and Outcomes of Young Onset Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: An Analysis from a Population-Based Database. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eusebi, L.H.; Cirota, G.G.; Zagari, R.M.; Ford, A.C. Global prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal cancer in individuals with gastro-oesophageal reflux: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2021, 70, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, N.J.; Falk, G.W.; Iyer, P.G.; Souza, R.F.; Yadlapati, R.H.; Sauer, B.G.; Wani, S. Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus: An Updated ACG Guideline. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 559–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eluri, S.; Reddy, S.; Ketchem, C.C.; Tappata, M.; Nettles, H.G.; Watts, A.E.; Cotton, C.C.; Dellon, E.S.; Shaheen, N.J. Low Prevalence of Endoscopic Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus in a Screening-Eligible Primary Care Population. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 1764–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Dent, J.; Armstrong, D.; Bergman, J.J.; Gossner, L.; Hoshihara, Y.; Jankowski, J.A.; Junghard, O.; Lundell, L.; Tytgat, G.N.; et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: The Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, J.H.; Shaheen, N.J. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 302–317.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasa, S.; Desai, M.; Vittal, A.; Chandrasekar, V.T.; Pervez, A.; Kennedy, K.F.; Gupta, N.; Shaheen, N.J.; Sharma, P. Estimating neoplasia detection rate (NDR) in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus based on index endoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2019, 68, 2122–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabau, M.; Luc, G.; Terrebonne, E.; Belleanne, G.; Vendrely, V.; Cunha, A.S.; Collet, D. Lymph node invasion might have more prognostic impact than R status in advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 2013, 205, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlottmann, F.; Patti, M.G.; Shaheen, N.J. Endoscopic Treatment of High-Grade Dysplasia and Early Esophageal Cancer. World J. Surg. 2017, 41, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennathur, A.; Farkas, A.; Krasinskas, A.M.; Ferson, P.F.; Gooding, W.E.; Gibson, M.K.; Schuchert, M.J.; Landreneau, R.J.; Luketich, J.D. Esophagectomy for T1 esophageal cancer: Outcomes in 100 patients and implications for endoscopic therapy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 87, 1048–1054, discussion 1054–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthi, R.; Singh, S.; Ragunathan, K.; Visrodia, K.; Wang, K.K.; Katzka, D.A.; Iyer, P.G. Factors Associated With Progression of Barrett’s Esophagus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 1046–1055.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, O.; May, A.; Manner, H.; Behrens, A.; Pohl, J.; Weferling, M.; Hartmann, U.; Manner, N.; Huijsmans, J.; Gossner, L.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection for patients with mucosal adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 652–660.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, T.; Nie, M.; Yin, K. The correlation between the margin of resection and prognosis in esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 21, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustgi, A.K.; El-Serag, H.B. Esophageal Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2499–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppedijk, V.; van der Gaast, A.; van Lanschot, J.J.; van Hagen, P.; van Os, R.; van Rij, C.M.; van der Sangen, M.J.; Beukema, J.C.; Rütten, H.; Spruit, P.H.; et al. Patterns of recurrence after surgery alone versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy and surgery in the CROSS trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthaner, R.; Wong, R.K.S.; Spithoff, K. Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site Group of Cancer Care Ontario’s Program in Evidence-based Care. Preoperative or postoperative therapy for resectable oesophageal cancer: An updated practice guideline. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 2010, 22, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Batran, S.E.; Homann, N.; Pauligk, C.; Goetze, T.O.; Meiler, J.; Kasper, S.; Kopp, H.G.; Mayer, F.; Haag, G.M.; Luley, K.; et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): A randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashist, Y.; Goyal, A.; Shetty, P.; Girnyi, S.; Cwalinski, T.; Skokowski, J.; Malerba, S.; Prete, F.P.; Mocarski, P.; Kania, M.K.; et al. Evaluating Postoperative Morbidity and Outcomes of Robotic-Assisted Esophagectomy in Esophageal Cancer Treatment—A Comprehensive Review on Behalf of TROGSS (The Robotic Global Surgical Society) and EFISDS (European Federation International Society for Digestive Surgery) Joint Working Group. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, F.; Hallemeier, C.L.; Lerut, T.; Fu, J. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet 2024, 404, 1991–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medical Research Council Oesophageal Cancer Working Party. Surgical resection with or without preoperative chemotherapy in oesophageal cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002, 359, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allum, W.H.; Stenning, S.P.; Bancewicz, J.; Clark, P.I.; Langley, R.E. Long-term results of a randomized trial of surgery with or without preoperative chemotherapy in esophageal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5062–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, J.S.; Kucera, S.T.; Lin, J.L.; Hoffe, S.E.; Strosberg, J.R.; Ahmed, I.; Dilling, T.J.; Stevens, C.W. Does Barrett’s esophagus respond to chemoradiation therapy for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus? Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 71, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raouf, A.; Evoy, D.; Carton, E.; Mulligan, E.; Griffin, M.; Sweeney, E.; Reynolds, J.V. Spontaneous and inducible apoptosis in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 85, 1781–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.J.; Zaidi, A.H.; Smith, M.A.; Omstead, A.N.; Kosovec, J.E.; Matsui, D.; Martin, S.A.; DiCarlo, C.; Werts, E.D.; Silverman, J.F.; et al. The Dynamic and Transient Immune Microenvironment in Locally Advanced Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Post Chemoradiation. Ann. Surg. 2018, 268, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraggi, D.; Fassan, M.; Bornschein, J.; Farinati, F.; Realdon, S.; Valeri, N.; Rugge, M. From Barrett metaplasia to esophageal adenocarcinoma: The molecular background. Histol. Histopathol. 2016, 31, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hagen, P.; Hulshof, M.C.C.M.; Van Lanschot, J.J.B.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Henegouwen, M.V.B.; Wijnhoven, B.P.L.; Richel, D.J.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G.A.P.; Hospers, G.A.P.; Bonenkamp, J.J.; et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, F.; de Manzoni, G.; Zanoni, A.; Grandinetti, A.; Capirci, C.; Pavarana, M.; Tomezzoli, A.; Rubello, D.; Cordiano, C. Neoadjuvant therapy with weekly docetaxel and cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil continuous infusion, and concurrent radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer produced a high percentage of long-lasting pathological complete response: A phase 2 study. Cancer 2013, 119, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almhanna, K.; Hoffe, S.; Strosberg, J.; Dinwoodie, W.; Meredith, K.; Shridhar, R. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with protracted infusion of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cisplatin for locally advanced resectable esophageal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2015, 6, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastroesophageal Cancer Research. Surveillance and Outcomes After Curative Resection for Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma. Available online: https://ge-cancer.com/testimonial/surveillance-and-outcomes-after-curative-resection-for-gastroesophageal-adenocarcinoma/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Sudo, K.; Taketa, T.; Correa, A.M.; Campagna, M.C.; Wadhwa, R.; Blum, M.A.; Komaki, R.; Lee, J.H.; Bhutani, M.S.; Weston, B.; et al. Locoregional failure rate after preoperative chemoradiation of esophageal adenocarcinoma and the outcomes of salvage strategies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 4306–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeppner, J.; Lordick, F.; Brunner, T.; Glatz, T.; Bronsert, P.; Röthling, N.; Schmoor, C.; Lorenz, D.; Ell, C.; Hopt, U.T.; et al. ESOPEC: Prospective randomized controlled multicenter phase III trial comparing perioperative chemotherapy (FLOT protocol) to neoadjuvant chemoradiation (CROSS protocol) in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus (NCT02509286). BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.J.; Ajani, J.A.; Kuzdzal, J.; Zander, T.; Van Cutsem, E.; Piessen, G.; Mendez, G.; Feliciano, J.; Motoyama, S.; Lièvre, A.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab in Resected Esophageal or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NCRT + Surgery (N = 18) | Surgery Alone (N = 10) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.4 ± 7.1 | 72.7 ± 7.8 | 0.064 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.41 | ||

| Male | 15 (83.3) | 7 (70) | |

| Female | 3 (16.7) | 3 (30) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| White | 9 (50) | 9 (90) | |

| Other | 9 (50) | 0 (0) | |

| Declined | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.57 | ||

| Not Hispanic | 10 (55.6) | 7 (70) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (38.9) | 2 (20) | |

| Other | 1 (5.50) | 1 (10) | |

| Health Class, Mean ± SD | |||

| ASA | 2.5 ± 0.79 | 2.4 ± 0.52 | 0.39 |

| CCI | 4.82 ± 1.62 | 5.1 ± 0.74 | 0.28 |

| BE Length, Mean ± SD | |||

| Circumferential Length (cm) | 4.20 ± 4.12 | 5.70 ± 4.43 | 0.13 |

| Maximum Length (cm) | 4.70 ± 3.20 | 7.51 ± 3.52 | 0.03 |

| Chemotherapy | N/A | N/A | |

| Carboplatin + Taxol, n (%) | 15 (83.3) | ||

| Cisplatin + 5-FU, n (%) | 2 (11.1) | ||

| FLOT, n (%) | 1 (5.6) | ||

| Radiation | N/A | N/A | |

| Cycles, Mean ± SD | 5.30 ± 1.99 |

| NCRT + Surgery (N = 18) | Surgery Alone (N = 10) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

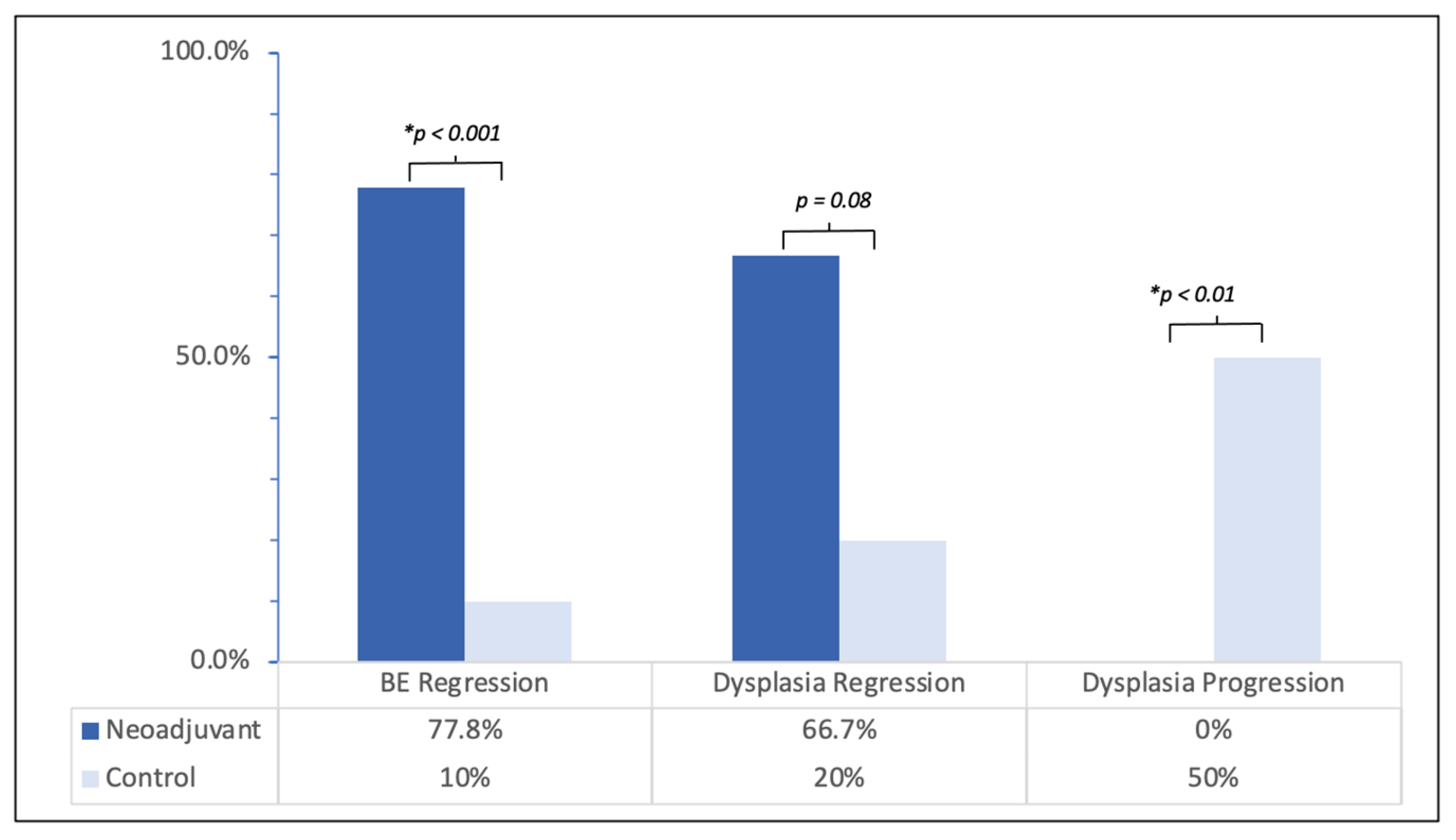

| BE Changes, n (%) | |||

| Total BE Regressed | 14 (77.8) | 1 (10) | <0.001 |

| BE Progression | 0 (0) | 7 (70) | <0.001 |

| Pre-EA Dysplasia, n (%) | |||

| Low Grade | 2 (16.7) | 1 (20) | 0.92 |

| High Grade | 10 (83.3) | 4 (80) | 0.62 |

| Post-EA Dysplasia, n (%) | |||

| Residual Dysplasia | 6 (33.3) | 8 (80) | 0.018 |

| Residual LGD | 3 (16.7) | 2 (20) | 0.3 |

| Residual HGD | 3 (16.7) | 6 (60) | 0.019 |

| NCRT + Surgery (n = 12) | Surgery Alone with Dysplasia (n = 5) | p Value | |

| Dysplasia Changes, n (%) | |||

| Dysplasia Regression | 8 (66.7) | 1 (20) | 0.079 |

| HGD Regression | 7 (70) | 1 (25) | 0.12 |

| Dysplasia Progression | 0 (0) | 5 (62.5) | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bachu, V.S.; Lee, J.M.; Wang, H.L.; Kozan, P.; Ramirez, M.; Garcia-Corella, J.; Ghassemi, K.A.; Muthusamy, V.; Issa, D. The Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy on Non-Tumorous Barrett’s Dysplasia of the Esophagus: A Multicenter Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010285

Bachu VS, Lee JM, Wang HL, Kozan P, Ramirez M, Garcia-Corella J, Ghassemi KA, Muthusamy V, Issa D. The Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy on Non-Tumorous Barrett’s Dysplasia of the Esophagus: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010285

Chicago/Turabian StyleBachu, Vismaya S., Jay M. Lee, Hanlin L. Wang, Phillip Kozan, Melanie Ramirez, Jose Garcia-Corella, Kevin A. Ghassemi, Venkataraman Muthusamy, and Danny Issa. 2026. "The Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy on Non-Tumorous Barrett’s Dysplasia of the Esophagus: A Multicenter Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010285

APA StyleBachu, V. S., Lee, J. M., Wang, H. L., Kozan, P., Ramirez, M., Garcia-Corella, J., Ghassemi, K. A., Muthusamy, V., & Issa, D. (2026). The Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy on Non-Tumorous Barrett’s Dysplasia of the Esophagus: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010285