Ixazomib-Lenalidomide-Dexamethasone for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: A Hungarian Real-World Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patients

3.2. Treatment Characteristics

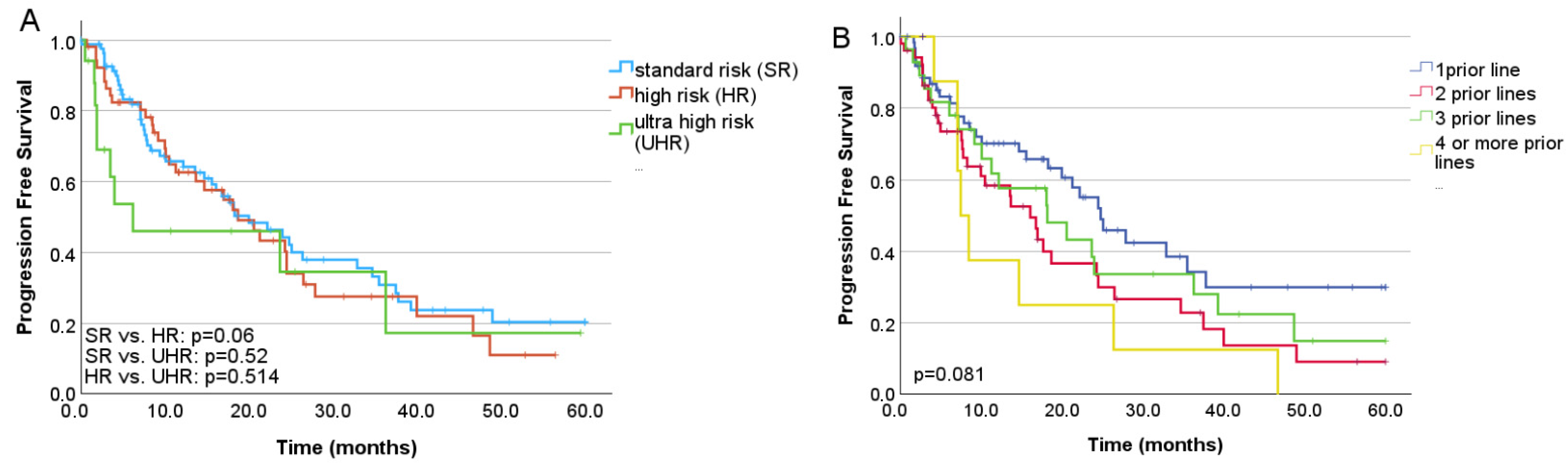

3.3. Treatment Efficacy

3.4. Safety

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEs | adverse events |

| ASCT | autologous stem cell transplantation |

| DRd | daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone |

| FISH | fluorescent in situ hybridization |

| FLC | free light chain |

| IMWG | international myeloma working group |

| IRd | ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone |

| ISS | international staging system |

| KRd | carfilzomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| RRMM | relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma |

| ORR | overall response rate |

| OS | overall survival |

References

- Vijjhalwar, R.; Kannan, A.; Fuentes-Lacouture, C.; Ramasamy, K. Approaches to Managing Relapsed Myeloma: Switching Drug Class or Retreatment with Same Drug Class? Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2025, 41, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Liu, H.D.; Rybicki, L.; Tomer, J.; Khouri, J.; Dean, R.M.; Faiman, B.M.; Kalaycio, M.; Samaras, C.J.; Majhail, N.S.; et al. Progression with clinical features is associated with worse subsequent survival in multiple myeloma. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman-Mazur, S.; Visram, A.; Kapoor, P.; Dispenzieri, A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Gertz, M.A.; Buadi, F.K.; Hayman, S.R.; Dingli, D.; Koruelis, T.; et al. Outcomes after biochemical or clinical progression in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhael, J.; Ismaila, N.; Cheung, M.C.; Costello, C.; Dhodapkar, M.V.; Kumar, S.; Lacy, M.; Lipe, B.; Little, R.F.; Nikonova, A.; et al. Treatment of Multiple Myeloma: ASCO and CCO Joint Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1228–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Moreau, P.; Terpos, E.; Mateos, M.V.; Zweegman, S.; Cook, G.; Delforge, M.; Hájek, R.; Schjesvold, F.; Cavo, M.; et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, N.; Hungria, V.T.M.; Chari, A.; Davies, F.E.; Cook, G.; Hájek, R.; Morgan, K.E.; Omel, J.; Terpos, E.; Thompson, M.A.; et al. Global Treatment Standard in Multiple Myeloma Remains Elusive: Updated Results from the INSIGHT MM Global, Prospective, Observational Study. Blood 2022, 140, 4269–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Terpos, E.; Boccadoro, M.; Moreau, P.; Mateos, M.V.; Zweegman, S.; Cook, G.; Engelhardt, M.; Delforge, M.; Hájek, R.; et al. EHA–EMN Evidence-Based Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with multiple myeloma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 22, 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.G.; Kumar, S.K.; Masszi, T.; Grzasko, N.; Bahlis, N.J.; Hansson, M.; Pour, L.; Sandhu, I.; Ganly, P.; Baker, B.W.; et al. Final Overall Survival Analysis of the TOURMALINE-MM1 Phase III Trial of Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2430–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, H.; Braun, M.; Reinhardt, H.; Rösner, A.; Ihorst, G.; Räder, J.; Wenger, S.; Brioli, A.; von Lilienfeld-Toal, M.; Klaiber-Hakimi, M.; et al. Ixazomib-lenalidomid-dexamethasone (IRd) in relapsed refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM)-multicenter real-world analysis from Germany and comparative review of the literature. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 3713–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.C.; Moon, J.H.; Park, S.S.; Koh, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Eom, H.S.; Shin, H.J.; Jung, S.H.; Do, Y.R.; Wilfred, G.; et al. Real-world effectiveness of ixazomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone in Asians with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Int. J. Hematol. 2025, 121, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batinić, J.; Dreta, B.; Rinčić, G.; Mrdeža, A.; Jakobac, K.M.; Krišto, D.R.; Vujčić, M.; Piršić, M.; Jonjić, Ž.; Periša, V.; et al. Outcomes of Ixazomib Treatment in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma: Insights from Croatian Cooperative Group for Hematologic Diseases (KROHEM). Medicina 2024, 60, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, G.; Nagy, Z.; Demeter, J.; Kosztolányi, S.; Szomor, Á.; Alizadeh, H.; Deák, B.; Schneider, T.; Plander, M.; Szendrei, T.; et al. Real World Efficacy and Safety Results of Ixazomib Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone Combination in Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: Data Collected from the Hungarian Ixazomib Named Patient Program. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2019, 25, 1615–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hájek, R.; Minařík, J.; Straub, J.; Pour, L.; Jungova, A.; Berdeja, J.; Boccadoro, M.; Brozova, L.; Spencer, A.; van Rhee, F.; et al. Ixazomib-Lenalidomide-Dexamethasone in Routine Clinical Practice: Effectiveness in Relapsed/refractory Multiple Myeloma. Future Oncol. 2021, 17, 2499–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovas, S.; Obajed Al-Ali, N.; Farkas, K.; Pinczés, L.I.; Varga, G.; Mikala, G.; Rajnics, P.; Kosztolányi, S.; Plander, M.; Pettendi, P.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Daratumumab, Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone Therapy in the First Relapse of Multiple Myeloma Patients—Real World Data from Hungary. J. Hematol. 2025, 14, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Paiva, B.; Anderson, K.C.; Durie, B.; Landgren, O.; Moreau, P.; Munshi, N.; Lonial, S.; Bladé, J.; Mateos, M.V.; et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e328–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, R.M.; Costello, C.L.; Birhiray, R.E.; Kambhampati, S.; Richter, J.; Abonour, R.; Lee, H.C.; Stokes, M.; Ren, K.; Stull, D.M.; et al. In-Class Transition from Bortezomib-Based Therapy to IRd is an Effective Approach in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Future Oncol. 2024, 20, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, P.G.; San Miguel, J.F.; Moreau, P.; Hajek, R.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Laubach, J.P.; Palumbo, A.; Luptakova, K.; Romanus, D.; Skacel, T.; et al. Interpreting clinical trial data in multiple myeloma: Translating findings to the real-world setting. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leleu, X.; Lee, H.C.; Zonder, J.A.; Macro, M.; Ramasamy, K.; Hulin, C. INSURE: A pooled analysis of ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone for relapsed/refractory myeloma in routine practice. Future Oncol. 2024, 20, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.C.; Ramasamy, K.; Macro, M.; Davies, F.E.; Abonour, R.; van Rhee, F.; Hungria, V.T.M.; Puig, N.; Ren, K.; Silar, J.; et al. Impact of prior lenalidomide or proteasome inhibitor exposure on the effectiveness of ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: A pooled analysis from the INSURE study. Eur. J. Haematol. 2024, 113, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fric, D.; Stork, M.; Boichuk, I.; Sandecka, V.; Adam, Z.; Krejci, M.; Ondrouskova, E.; Fidrichova, A.; Radova, L.; Knechtova, Z.; et al. Efficacy of ixazomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone regimen in daratumumab-exposed relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients: A retrospective analysis. Eur. J. Haematol. 2024, 113, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minarik, J.; Pour, L.; Latal, V.; Jelinek, T.; Straub, J.; Jungova, A.; Radocha, J.; Pavlicek, P.; Stork, M.; Pika, T.; et al. Lenalidomide based triplets in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: Analysis of the Czech Myeloma Group. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ailawadhi, S.; Cheng, M.; Cherepanov, D.; DerSarkissian, M.; Stull, D.M.; Hilts, A.; Chun, J.; Duh, M.S.; Sanchez, L. Comparative effectiveness of lenalidomide/dexamethasone-based triplet regimens for treatment of relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma in the United States: An analysis of real-world electronic health records data. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2024, 50, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Takezako, N.; Ito, S.; Suzuki, K.; Handa, H.; Chou, T.; Yoshida, T.; Mori, I.; Shinozaki, T.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ixazomib Plus Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone Following Injectable PI-Based Therapy in Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Ann. Hematol. 2023, 102, 2493–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.; Pawlyn, C.; Royle, K.L.; Senior, E.R.; Everritt, D.; Bird, J.; Bowcock, S.; Dawkins, B.; Drayson, M.; Gillson, S.; et al. IMWG Frailty Score-Adjusted Therapy Delivery Reduces the Early Mortality Risk in Newly Diagnosed Tne Multiple Myeloma: Results of the UK Myeloma Research Alliance (UK-MRA) Myeloma XIV Fitness Trial. Blood 2024, 144, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Wang, Y.T.; Liu, P.; Lu, M.Q.; Zhuang, J.L.; Zhang, M.; Xia, Z.J.; Li, Z.L.; Yang, Y.; Yan, Z.Y.; et al. Ixazomib-based frontline therapy followed by ixazomib maintenance in frail elderly newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma: A prospective multicenter study. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 68, 102431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stege, C.A.M.; Nasserinejad, K.; van der Spek, E.; Bilgin, Y.M.; Kentos, A.; Sohne, M.; van Kampen, R.J.W.; Ludwig, I.; Thielen, N.; Durdu-Rayman, N.; et al. Ixazomib, Daratumumab, and Low-Dose Dexamethasone in Frail Patients with Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: The Hovon 143 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2758–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayto, R.; Annibali, O.; Biedermann, P.; Roset, M.; Sánchez, E.; Kotb, R. The EASEMENT study: A multicentre, observational, cross-sectional study to evaluate patient preferences, treatment satisfaction, quality of life, and healthcare resource use in patients with multiple myeloma receiving injectable-containing or fully oral therapies. Eur. J. Haematol. 2024, 112, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, M.; Lin, J.; Yang, X.; Huang, P.; Zheng, X. Safety assessment of proteasome inhibitors real world adverse event analysis from the FAERS database. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.Y.; Min, C.K.; Eom, H.S.; Jung, J.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.H.; Yoo, H.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Byun, J.M.; Kim, S.H.; et al. Real-World Comparison of Carfilzomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone Versus Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: KMM2004 Study. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2025, 25, 2152–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.J.; Sayer, M.; Naqvi, A.A.; Mai, K.T.; Patel, P.M.; Lee, L.X.; Ozaki, A.F. Balancing the Risk of Cardiotoxicity Outcomes in Treatment Selection for Multiple Myeloma: A Retrospective Multicenter Evaluation of Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone (IRd) Versus Carfilzomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone (KRd). eJHaem 2025, 6, e70038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Whole Cohort | Second Line | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 152 | 65 |

| Male/female (%) | 66/86 (43.4/56.5) | 27/38 (41.5/58.5) |

| Median age at the start of ixazomib (years) (min.–max.) | 73.7 (49.3–90.8) | 73.8 (50.8–90.8) |

| ISS I (%) | 39 (25.7) | 16 (24.6) |

| ISS II (%) | 51 (33.6) | 21 (32.3) |

| ISS III (%) | 47 (30.9) | 21 (32.3) |

| ISS NA (%) | 15 (9.9) | 7 (10.8) |

| FISH | ||

| Standard risk | 45 (29.6) | 20 (30.8) |

| High risk | 52 (34.2) | 24 (36.9) |

| Ultra-high risk | 17 (11.2) | 4 (6.2) |

| NA | 38 (25) | 17 (26.2) |

| M-protein | ||

| IgG kappa/lambda (%) | 64/31 (42.1/20.4) | 28/11 (43.1/16.9) |

| FLC kappa/lambda | 12/5 (7.9/3.3) | 8/2 (12.3/3.1) |

| other (%) | 40 (26.3) | 19 (29.2) |

| Previous lines | ||

| 1 | 66 (43.4) | |

| 2 | 50 (32.9) | |

| 3 | 25 (16.4) | |

| 4 or more | 11 (7.2) | |

| Lenalidomide | ||

| naïve | 42 (27.6) | 27 (41.5) |

| exposed | 90 (59.2) | 32 (49.5) |

| refractory | 20 (13.2) | 6 (9.2) |

| Daratumumab | ||

| naïve | 131 (86.2) | 63 (97) |

| exposed | 13 (8.6) | 1 (1.5) |

| refractory | 8 (5.3) | 1 (1.5) |

| Pomalidomide | ||

| naïve | 140 (92.1) | 65 (100) |

| exposed | 8 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| refractory | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0) |

| Prior ASCT | ||

| yes | 53 (34.9) | 23 (35.4) |

| no | 99 (65.1) | 42 (64.6) |

| Reason for ixazomib initiation | ||

| Clinical progression | 58 (38.2) | 26 (40) |

| Biochemical progression | 81 (53.3) | 31 (47.7) |

| Toxicity of previous therapy | 13 (8.5) | 8 (12.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sánta, H.; Regáli, L.; Váróczy, L.; Szita, V.; Wiedemann, Á.; Varju, L.; Rejtő, L.; Bartha, N.S.; Máté, D.; Masszi, A.; et al. Ixazomib-Lenalidomide-Dexamethasone for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: A Hungarian Real-World Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010286

Sánta H, Regáli L, Váróczy L, Szita V, Wiedemann Á, Varju L, Rejtő L, Bartha NS, Máté D, Masszi A, et al. Ixazomib-Lenalidomide-Dexamethasone for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: A Hungarian Real-World Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010286

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánta, Hermina, Laura Regáli, László Váróczy, Virág Szita, Ádám Wiedemann, Lóránt Varju, László Rejtő, Norbert Sándor Bartha, Dorottya Máté, András Masszi, and et al. 2026. "Ixazomib-Lenalidomide-Dexamethasone for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: A Hungarian Real-World Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010286

APA StyleSánta, H., Regáli, L., Váróczy, L., Szita, V., Wiedemann, Á., Varju, L., Rejtő, L., Bartha, N. S., Máté, D., Masszi, A., Plander, M., Kosztolányi, S., Hussain, A., Pettendi, P., Istenes, I., Szomor, Á., Reményi, P., Masszi, T., Varga, G., & Mikala, G. (2026). Ixazomib-Lenalidomide-Dexamethasone for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: A Hungarian Real-World Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010286