Cardiac Overload and Heart Failure Risk by NT-proBNP Levels in Older Adults with COPD Eligible for Single-Inhaler Triple Therapy: A Multicenter Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Clinical and Laboratory Assessments

2.3. NT-proBNP Assay

2.4. Classification of HF Risk According to Age- and Comorbidities-Adjusted NT-proBNP

- -

- Chronic kidney disease: Given the proportional increment of NT-proBNP with the decline in renal function (eGFR), the threshold was increased by 15% for eGFR 45–60 mL/min/1.73 m2, by 25% for eGFR 30–45 mL/min/1.73 m2 and by 35% for eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

- -

- Atrial fibrillation: The derangement of atrial electrical activity can itself increase NT-proBNP levels due to myocardial stretch; therefore, the threshold was increased by 100% for heart rate > 90 bpm and by 50% for heart rate ≤ 90 bpm.

- -

- Obesity: Patients with higher BMI tend to have lower circulating NT-proBNP due to augmented clearance by adipose tissue (increased degradation); therefore, the threshold was decreased by a range of 25 to 40% based on the specific BMI class.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

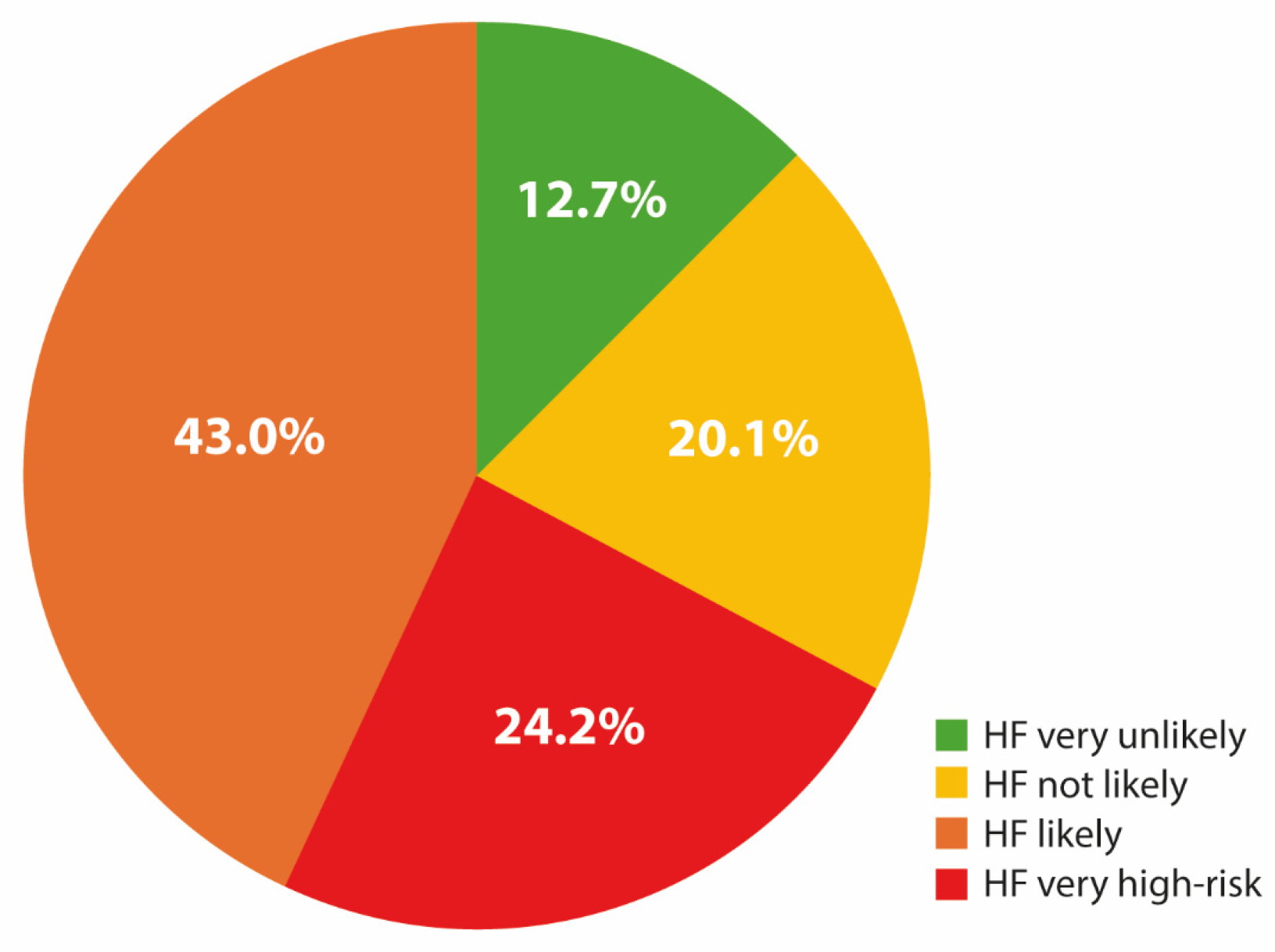

3.2. Predictors of Cardiac Overload or HF Risk

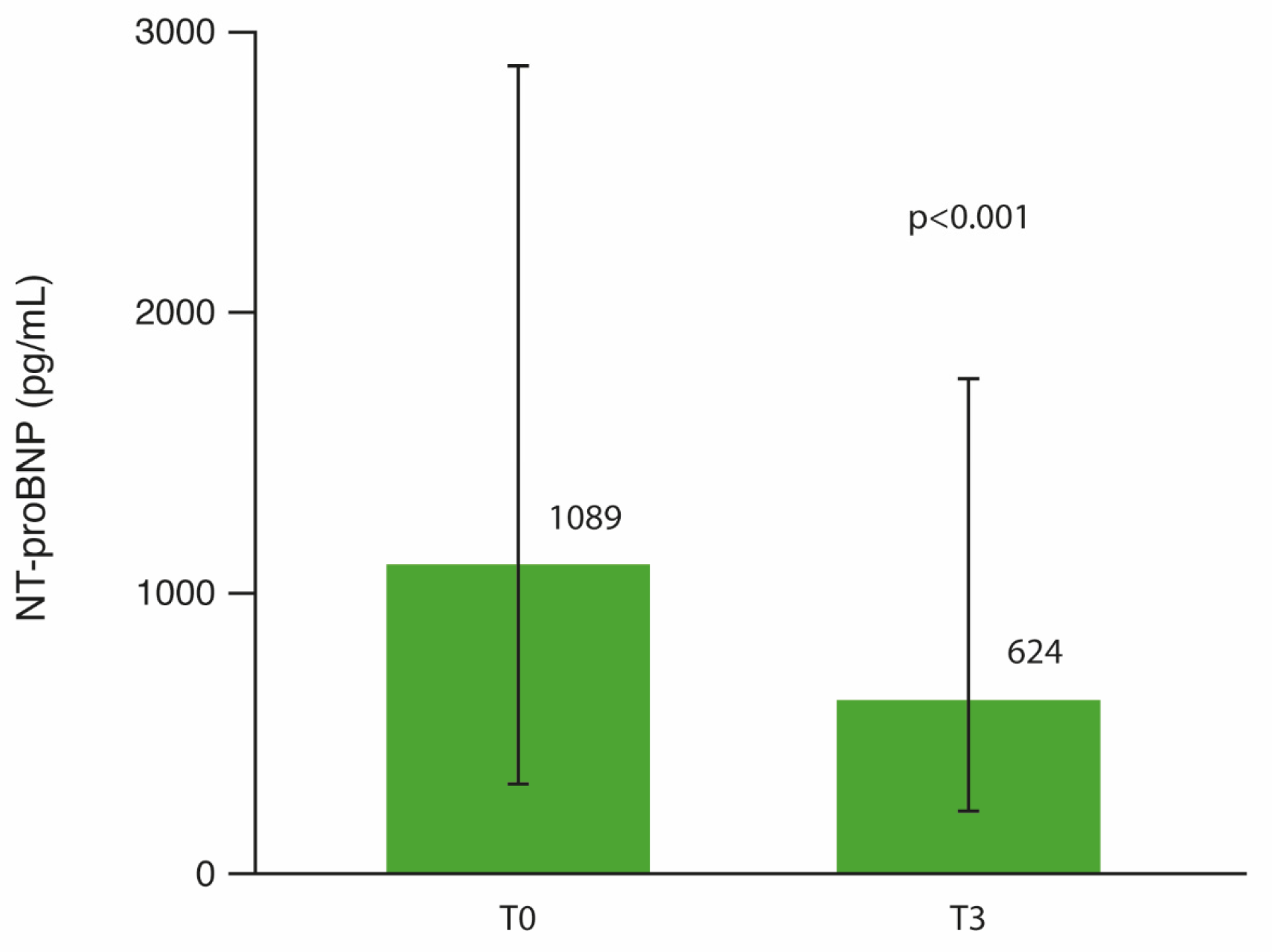

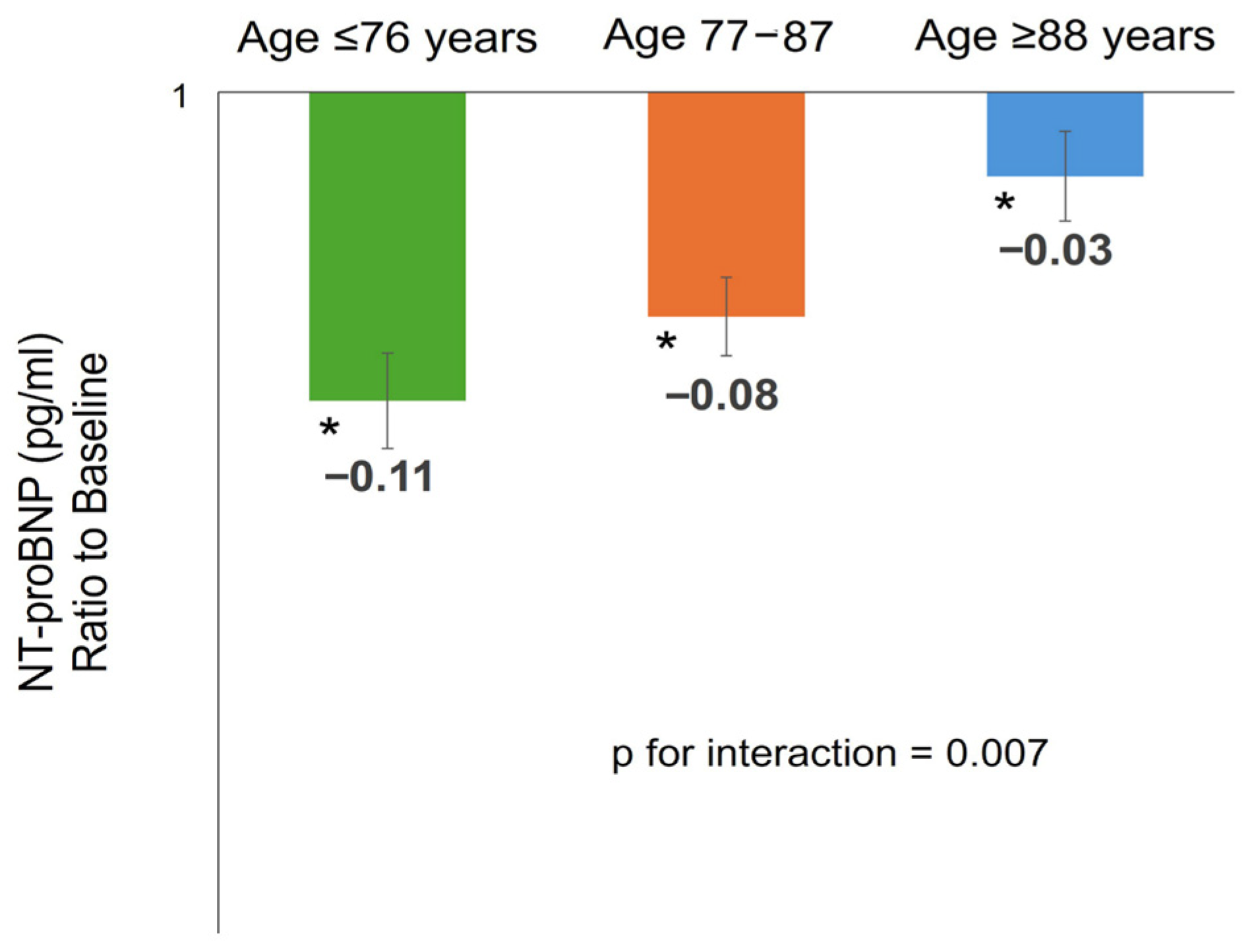

3.3. NT-proBNP Changes After 3 Months of SITT

3.4. Cardiovascular Therapy Adjustments During Follow-Up

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boers, E.; Barrett, M.; Su, J.G.; Benjafield, A.V.; Sinha, S.; Kaye, L.; Zar, H.J.; Vuong, V.; Tellez, D.; Gondalia, R.; et al. Global Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease through 2050. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2346598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, K.F.; Hurst, J.R.; Suissa, S. Cardiovascular Disease and COPD: Dangerous Liaisons? Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 180057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solidoro, P.; Albera, C.; Ribolla, F.; Bellocchia, M.; Brussino, L.; Patrucco, F. Triple Therapy in COPD: Can We Welcome the Reduction in Cardiovascular Risk and Mortality? Front. Med. 2022, 9, 816843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F.J.; Rabe, K.F.; Ferguson, G.T.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Singh, D.; Wang, C.; Rossman, K.; St Rose, E.; Trivedi, R.; Ballal, S.; et al. Reduced All-Cause Mortality in the ETHOS Trial of Budesonide/Glycopyrrolate/Formoterol for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter, Parallel-Group Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geffen, W.H.; Tan, D.J.; Walters, J.A.; Walters, E.H. Inhaled Corticosteroids with Combination Inhaled Long-Acting Beta2-Agonists and Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonists for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, CD011600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carter, P.R.; Lagan, J.; Fortune, C.; Bhatt, D.L.; Vestbo, J.; Niven, R.; Chaudhuri, N.; Schelbert, E.; Potluri, R.; Miller, C. The Association of Cardiovascular Disease with Respiratory Disease and Impact on Mortality. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, M.; Franssen, F.M.E.; Olschewski, H.; Lainscak, M.; Böhm, M.; Tavazzi, L.; Rosenkranz, S. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Gaps in Patients with Heart Failure and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santus, P.; Di Marco, F.; Braido, F.; Contoli, M.; Corsico, A.G.; Micheletto, C.; Pelaia, G.; Radovanovic, D.; Rogliani, P.; Saderi, L.; et al. Exacerbation Burden in COPD and Occurrence of Mortality in a Cohort of Italian Patients: Results of the Gulp Study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2024, 19, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Canepa, M.; Catapano, G.A.; Marvisi, M.; Oliva, F.; Passantino, A.; Sarzani, R.; Tarsia, P.; Versace, A.G. Implementation of the Care Bundle for the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease with/without Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, P. GOLD COPD Report: 2024 Update. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosano, G.M.C.; Teerlink, J.R.; Kinugawa, K.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Chioncel, O.; Fang, J.; Greenberg, B.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Imamura, T.; Inomata, T.; et al. The Use of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure. A Clinical Consensus Statement of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC, the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA), and the Japanese Heart Failure Society (JHFS). J. Card. Fail. 2025, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, H.; Albert, N.M.; Coats, A.J.S.; Anker, S.D.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Butler, J.; Chioncel, O.; Defilippi, C.R.; Drazner, M.H.; Felker, G.M.; et al. Natriuretic Peptides: Role in the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America and Japanese Heart Failure Society. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roalfe, A.K.; Lay-Flurrie, S.L.; Ordóñez-Mena, J.M.; Goyder, C.R.; Jones, N.R.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Taylor, C.J. Long Term Trends in Natriuretic Peptide Testing for Heart Failure in UK Primary Care: A Cohort Study. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 43, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayes-Genis, A.; Docherty, K.F.; Petrie, M.C.; Januzzi, J.L.; Mueller, C.; Anderson, L.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Chioncel, O.; Cleland, J.G.F.; et al. Practical Algorithms for Early Diagnosis of Heart Failure and Heart Stress Using NT-ProBNP: A Clinical Consensus Statement from the Heart Failure Association of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Murphy, S.A.; Wasserman, S.M.; Stein, E.A.; Ceška, R.; López-Miranda, J.; Georgiev, B.; Lorenzatti, A.J.; Tikkanen, M.J.; et al. Comparison of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Assessment by Martin/Hopkins Estimation, Friedewald Estimation, and Preparative Ultracentrifugation: Insights from the FOURIER Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.-M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Lewandrowski, E.; Januzzi, J.L.; Green, S.M.; Tannous, B.; Wu, A.H. Multi-Center Validation Response Biomedical Corporation RAMP® NT-ProBNP Assay Comparison Roche Diagnostics GmbH Elecsys® ProBNP Assay. Clin. Chim. Acta 2007, 386, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Ding, P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicori, P.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Clark, A.L. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Heart Failure: A Breathless Conspiracy. Cardiol. Clin. 2022, 40, 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Celli, B.R.; Fabbri, L.M.; Aaron, S.D.; Agusti, A.; Brook, R.D.; Criner, G.J.; Franssen, F.M.E.; Humbert, M.; Hurst, J.R.; Montes de Oca, M.; et al. Differential Diagnosis of Suspected Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations in the Acute Care Setting: Best Practice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllerova, H.; Agusti, A.; Erqou, S.; Mapel, D.W. Cardiovascular Comorbidity in COPD: Systematic Literature Review. Chest 2013, 144, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagan, J.; Schelbert, E.B.; Naish, J.H.; Vestbo, J.; Fortune, C.; Bradley, J.; Belcher, J.; Hearne, E.; Ogunyemi, F.; Timoney, R.; et al. Mechanisms Underlying the Association of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease with Heart Failure. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 1963–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.M.; Kawut, S.M.; Bluemke, D.A.; Basner, R.C.; Gomes, A.S.; Hoffman, E.; Kalhan, R.; Lima, J.A.C.; Liu, C.-Y.; Michos, E.D.; et al. Pulmonary Hyperinflation and Left Ventricular Mass: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis COPD Study. Circulation 2013, 127, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.M.; Prince, M.R.; Hoffman, E.A.; Bluemke, D.A.; Liu, C.-Y.; Rabinowitz, D.; Hueper, K.; Parikh, M.A.; Gomes, A.S.; Michos, E.D.; et al. Impaired Left Ventricular Filling in COPD and Emphysema: Is It the Heart or the Lungs? The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis COPD Study. Chest 2013, 144, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Lei, T.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Feng, Z.; Shuai, T.; Guo, H.; Liu, J. NT-ProBNP in Different Patient Groups of COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2023, 18, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabria, S.; Ronconi, G.; Dondi, L.; Dondi, L.; Dell’Anno, I.; Nordon, C.; Rhodes, K.; Rogliani, P.; Dentali, F.; Martini, N.; et al. Cardiovascular Events after Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Results from the EXAcerbations of COPD and Their OutcomeS in CardioVascular Diseases Study in Italy. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 127, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, K.M.A.; Baak, B.N.; Lemmens, L.; Penning-van Beest, F.J.A.; Bengtsson, C.; Lobier, M.; Hoti, F.; Vojinovic, D.; van Burk, L.; Rhodes, K.; et al. Risk of Cardiovascular Events after an Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Results from the EXACOS-CV Cohort Study Using the PHARMO Data Network in the Netherlands. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaki, W.W.; Xia, M.; Murray, S.; Curtis, J.L.; Barr, R.G.; Bhatt, S.P.; Bleecker, E.R.; Hansel, N.N.; Cooper, C.B.; Dransfield, M.T.; et al. NT-ProBNP in Stable COPD and Future Exacerbation Risk: Analysis of the SPIROMICS Cohort. Respir. Med. 2018, 140, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spannella, F.; Giulietti, F.; Cocci, G.; Landi, L.; Lombardi, F.E.; Borioni, E.; Cenci, A.; Giordano, P.; Sarzani, R. Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Oldest Adults: Predictors of in-Hospital Mortality and Need for Post-Acute Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavasini, R.; Tavazzi, G.; Biscaglia, S.; Guerra, F.; Pecoraro, A.; Zaraket, F.; Gallo, F.; Spitaleri, G.; Contoli, M.; Ferrari, R.; et al. Amino Terminal pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide Predicts All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2017, 14, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Similowski, T.; Agustí, A.; MacNee, W.; Schönhofer, B. The Potential Impact of Anaemia of Chronic Disease in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2006, 27, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, I.S.; Gupta, P. Anemia and Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure: Current Concepts and Emerging Therapies. Circulation 2018, 138, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohlfeld, J.M.; Vogel-Claussen, J.; Biller, H.; Berliner, D.; Berschneider, K.; Tillmann, H.-C.; Hiltl, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Welte, T. Effect of Lung Deflation with Indacaterol plus Glycopyrronium on Ventricular Filling in Patients with Hyperinflation and COPD (CLAIM): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Crossover, Placebo-Controlled, Single-Centre Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, K.F.; Martinez, F.J.; Singh, D.; Trivedi, R.; Jenkins, M.; Darken, P.; Aurivillius, M.; Dorinsky, P. Improvements in Lung Function with Budesonide/Glycopyrrolate/Formoterol Fumarate Metered Dose Inhaler versus Dual Therapies in Patients with COPD: A Sub-Study of the ETHOS Trial. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2021, 15, 17534666211034328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.K.; Criner, G.J.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Jones, C.E.; Kilbride, S.; Lange, P.; Lettis, S.; Lipson, D.A.; Lomas, D.A.; et al. The Effect of Inhaled Corticosteroid Withdrawal and Baseline Inhaled Treatment on Exacerbations in the IMPACT Study. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Triple Therapy on Mortality and Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Moderate to Severe COPD: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C.P.; Hurst, J.R.; Hawkins, N.M.; Bourbeau, J.; Han, M.K.; Lam, C.S.P.; Marciniuk, D.D.; Price, D.; Stolz, D.; Gluckman, T.; et al. Identification and Management of Cardiopulmonary Risk in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Multidisciplinary Consensus and Modified Delphi Study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heart Failure Risk According to the 2023 ESC/HFA Clinical Consensus | NT-proBNP Cut-Points | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Heart failure very unlikely | ≤125 pg/mL | Evaluation for a non-cardiac cause of symptoms |

| Heart failure not likely | Gray zone | Consider alternative diagnosis and elective echocardiography if clinical suspicion remains |

| Heart failure likely | Treat as appropriate; arrange for echocardiography within 6 weeks | |

| <50 years old | ≥125 pg/mL | |

| 50–74 years old | ≥250 pg/mL | |

| ≥75 years old | ≥500 pg/mL | |

| Heart failure very high-risk | ≥2000 pg/mL | Priority echocardiography and evaluation by heart failure team within 2 weeks |

| Demographics, Anthropometrics and Comorbidities | Overall Population (n = 165) | HF Very Unlikely/Not Likely (n = 54) | HF Likely (n = 71) | HF Very High-Risk (n = 40) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 80.7 ± 9.7 | 76.0 ± 9.1 | 80.4 ± 9.3 | 87.8 ± 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 47.9% | 63.0% | 39.4% | 42.5% | 0.025 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.8 ± 5.6 | 27.1 ± 6.4 | 26.7 ± 4.7 | 26.4 ± 6.1 | 0.877 |

| Recent AECOPD (previous 30 days) | 51.5% | 9.3% | 59.2% | 95.0% | <0.001 |

| T2DM | 33.6% | 32.4% | 35.1% | 32.4% | 0.950 |

| Hypertension | 83.3% | 71.4% | 91.1% | 85.3% | 0.033 |

| Dyslipidemia | 63.9% | 69.6% | 56.3% | 73.1% | 0.288 |

| Coronary artery disease | 29.1% | 13.2% | 31.6% | 41.0% | 0.023 |

| Known peripheral artery disease | 29.2% | 39.1% | 29.8% | 19.2% | 0.308 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 12.5% | 16.7% | 10.7% | 11.8% | 0.572 |

| History of atrial fibrillation | 37.8% | 21.1% | 37.9% | 53.8% | 0.012 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 50.7% | 26.3% | 56.7% | 66.7% | 0.001 |

| Smoking status | 78.9% | 80.4% | 81.8% | 71.4% | 0.455 |

| Pack per year | 25 (13–40.5) | 18 (10–50) | 25 (14–35) | 30 (17.5–40) | 0.781 |

| Cardiovascular therapies | |||||

| RAASi | 63.9% | 45.5% | 71.8% | 68.2% | 0.107 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 20.5% | 27.3% | 17.9% | 18.2% | 0.458 |

| Diuretics | 55.4% | 36.4% | 61.5% | 63.6% | 0.109 |

| Other anti-hypertensives * | 55.9% | 41.3% | 59.7% | 68.6% | 0.037 |

| Number of anti-hypertensive drugs | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 0.018 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 48.2% | 47.2% | 52.1% | 43.3% | 0.745 |

| Main laboratory and spirometry parameters | |||||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 59.8 ± 21.1 | 70.1 ± 18.1 | 57.7 ± 20.7 | 52.4 ± 21.1 | 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 826 (262–2551.5) | 168 (99–290.3) | 1079 (580–1611) | 4662 (3166.5–7327) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.1 ± 1.6 | 12.7 ± 1.5 | 12.0 ± 1.7 | 11.6 ± 1.5 | 0.010 |

| Eosinophils (/mmc) | 206.5 (144.3–287.5) | 212 (155–279.5) | 191 (120–241) | 223.5 (167.5–315.8) | 0.140 |

| FEV1 (% predicted) ** | 60.1 ± 16.4 | 58.4 ± 17.4 | 62.1 ± 15.7 | 61.3 ± 15.7 | 0.644 |

| Variable | Wald | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AECOPD within the previous 30 days | 5.7 | 9.0 (1.5–54.7) | 0.017 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 3.6 | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | 0.057 |

| Number of anti-hypertensive drugs | 5.7 | 2.7 (1.1–6.6) | 0.031 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sarzani, R.; Spannella, F.; Laureti, G.; Giordano, P.; Giulietti, F.; Gezzi, A.; Mari, P.-V.; Coppola, A.; Galeazzi, R.; Rosati, Y.; et al. Cardiac Overload and Heart Failure Risk by NT-proBNP Levels in Older Adults with COPD Eligible for Single-Inhaler Triple Therapy: A Multicenter Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010277

Sarzani R, Spannella F, Laureti G, Giordano P, Giulietti F, Gezzi A, Mari P-V, Coppola A, Galeazzi R, Rosati Y, et al. Cardiac Overload and Heart Failure Risk by NT-proBNP Levels in Older Adults with COPD Eligible for Single-Inhaler Triple Therapy: A Multicenter Longitudinal Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):277. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010277

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarzani, Riccardo, Francesco Spannella, Giorgia Laureti, Piero Giordano, Federico Giulietti, Alessandro Gezzi, Pier-Valerio Mari, Angelo Coppola, Roberta Galeazzi, Yuri Rosati, and et al. 2026. "Cardiac Overload and Heart Failure Risk by NT-proBNP Levels in Older Adults with COPD Eligible for Single-Inhaler Triple Therapy: A Multicenter Longitudinal Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010277

APA StyleSarzani, R., Spannella, F., Laureti, G., Giordano, P., Giulietti, F., Gezzi, A., Mari, P.-V., Coppola, A., Galeazzi, R., Rosati, Y., Kamberi, E., Stronati, A., Resedi, A., & Landolfo, M. (2026). Cardiac Overload and Heart Failure Risk by NT-proBNP Levels in Older Adults with COPD Eligible for Single-Inhaler Triple Therapy: A Multicenter Longitudinal Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010277