Effects of Web-Based Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy on Hyoid Bone Position in Adults with Mild to Moderate Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Evidence from an Estonian Substudy of a Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Background/Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

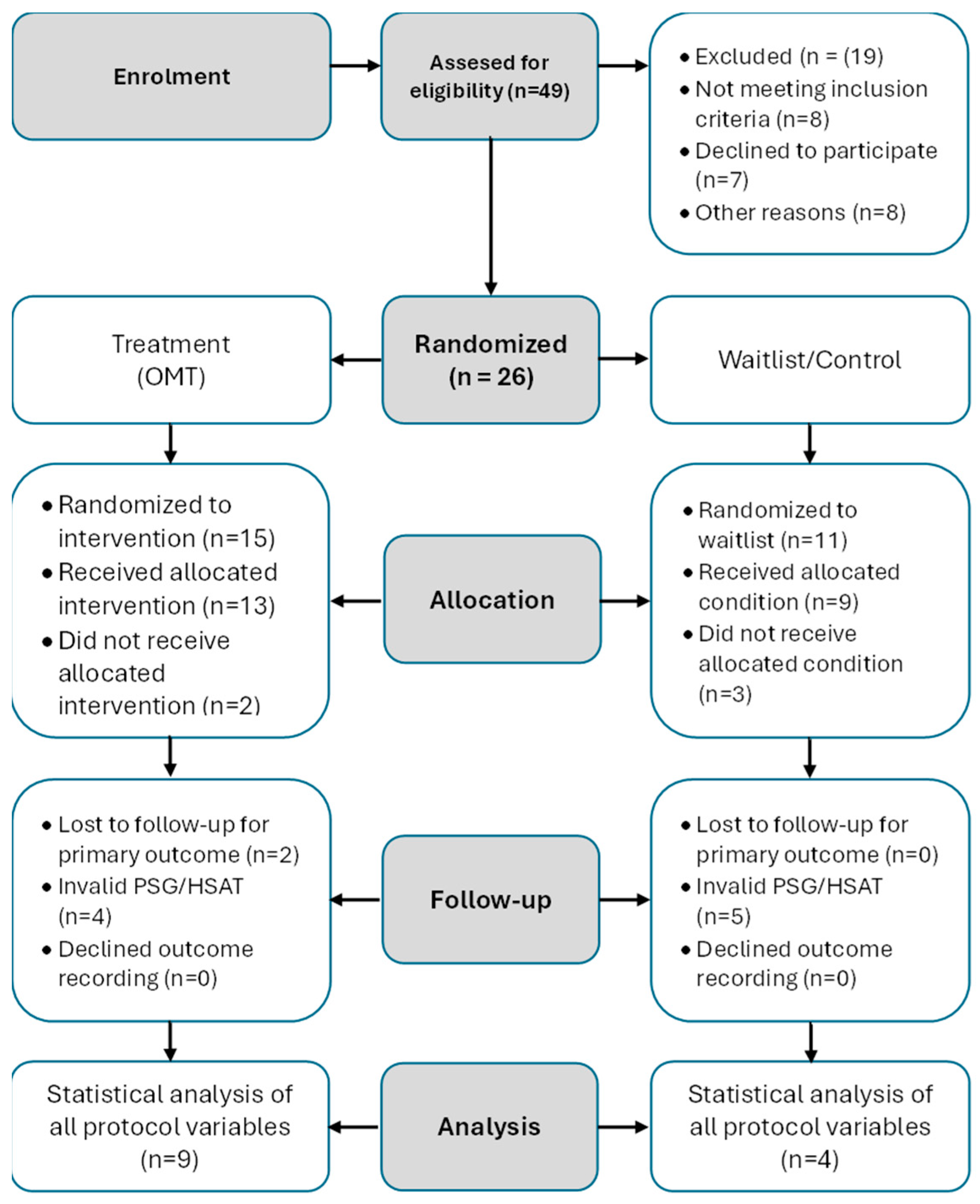

2.1. Study Design and Ethics Ethical Approval

2.2. Participation and Randomization

2.3. Estonian Subsample and Participant Selection

2.4. Outcome Measurements

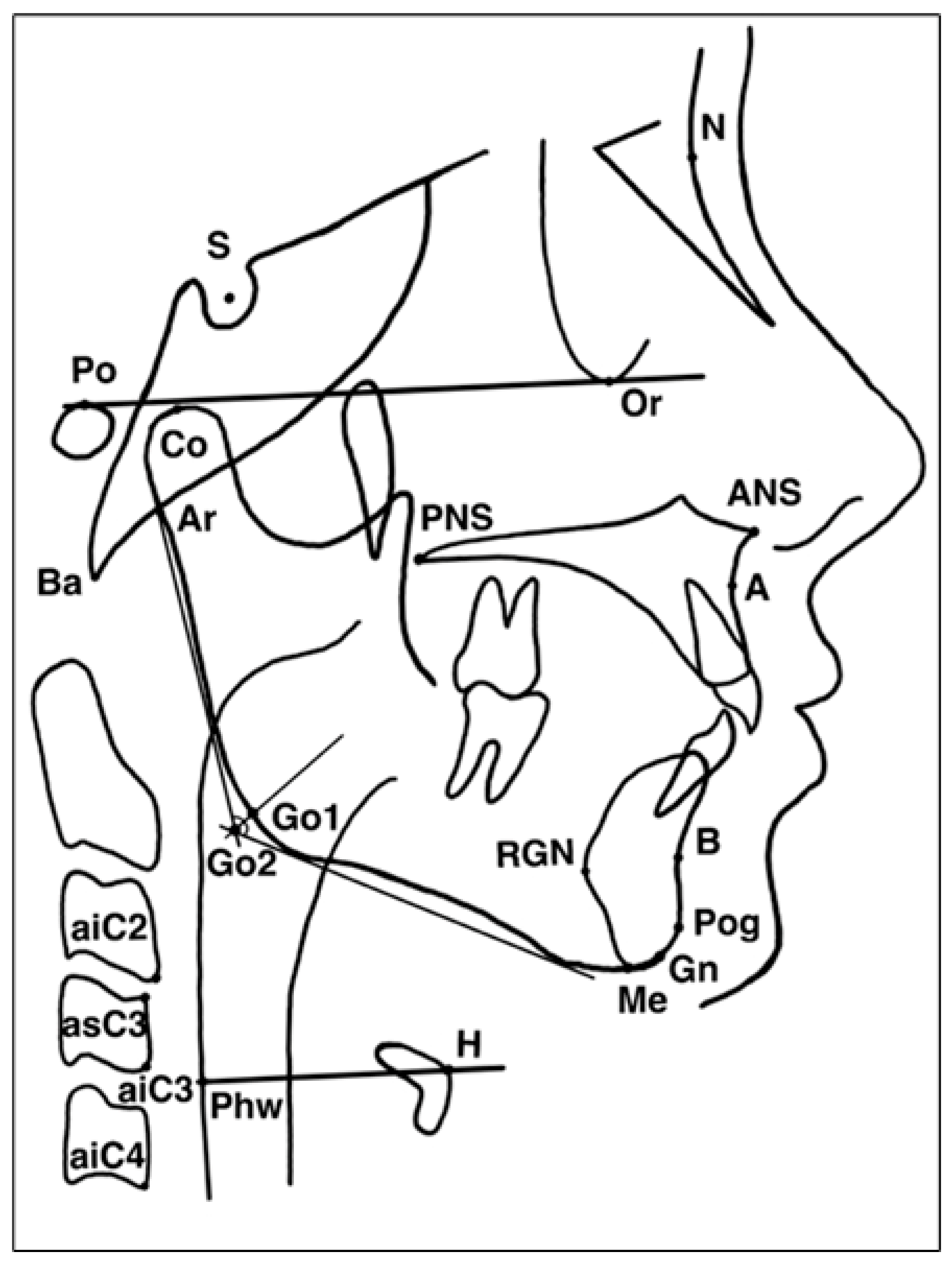

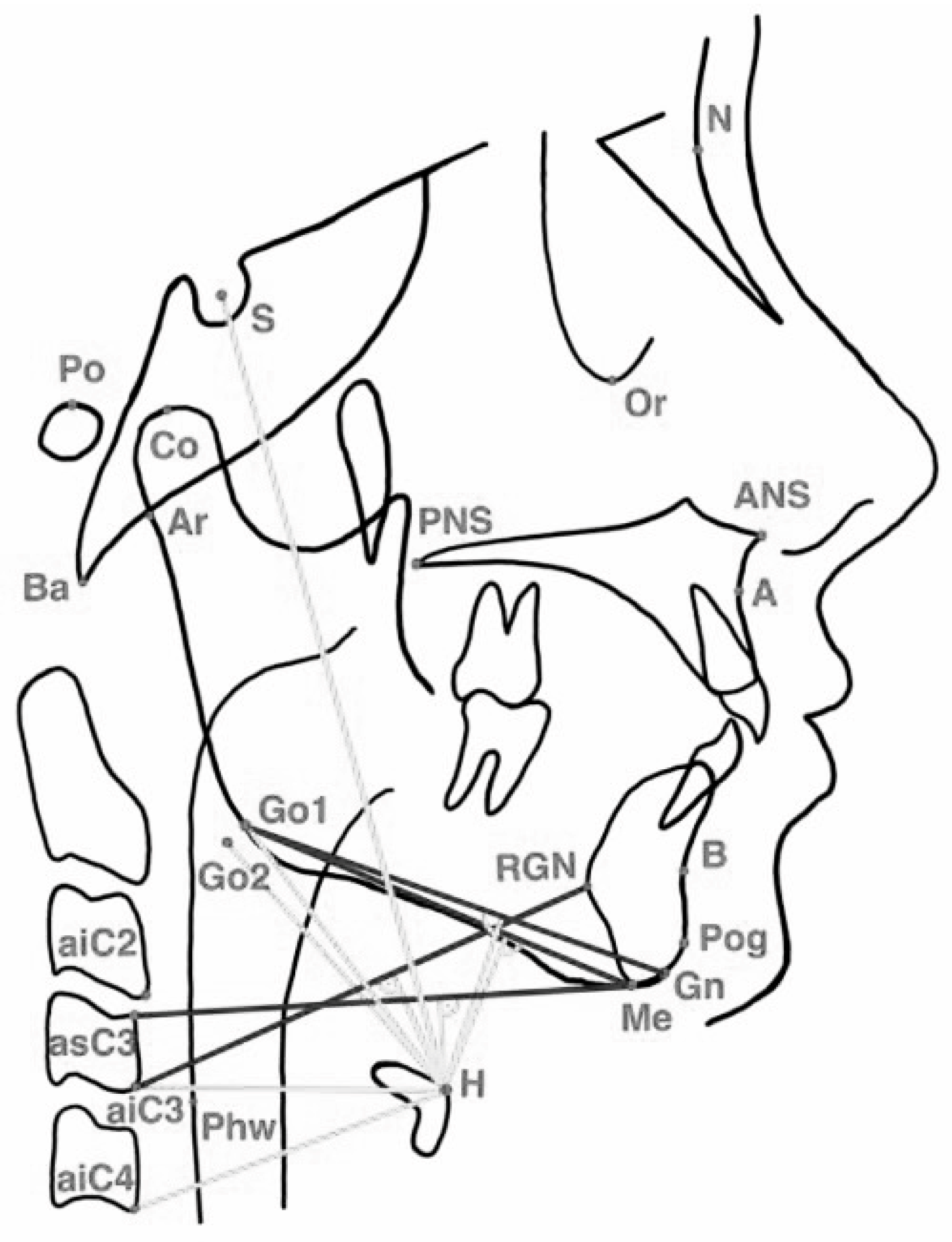

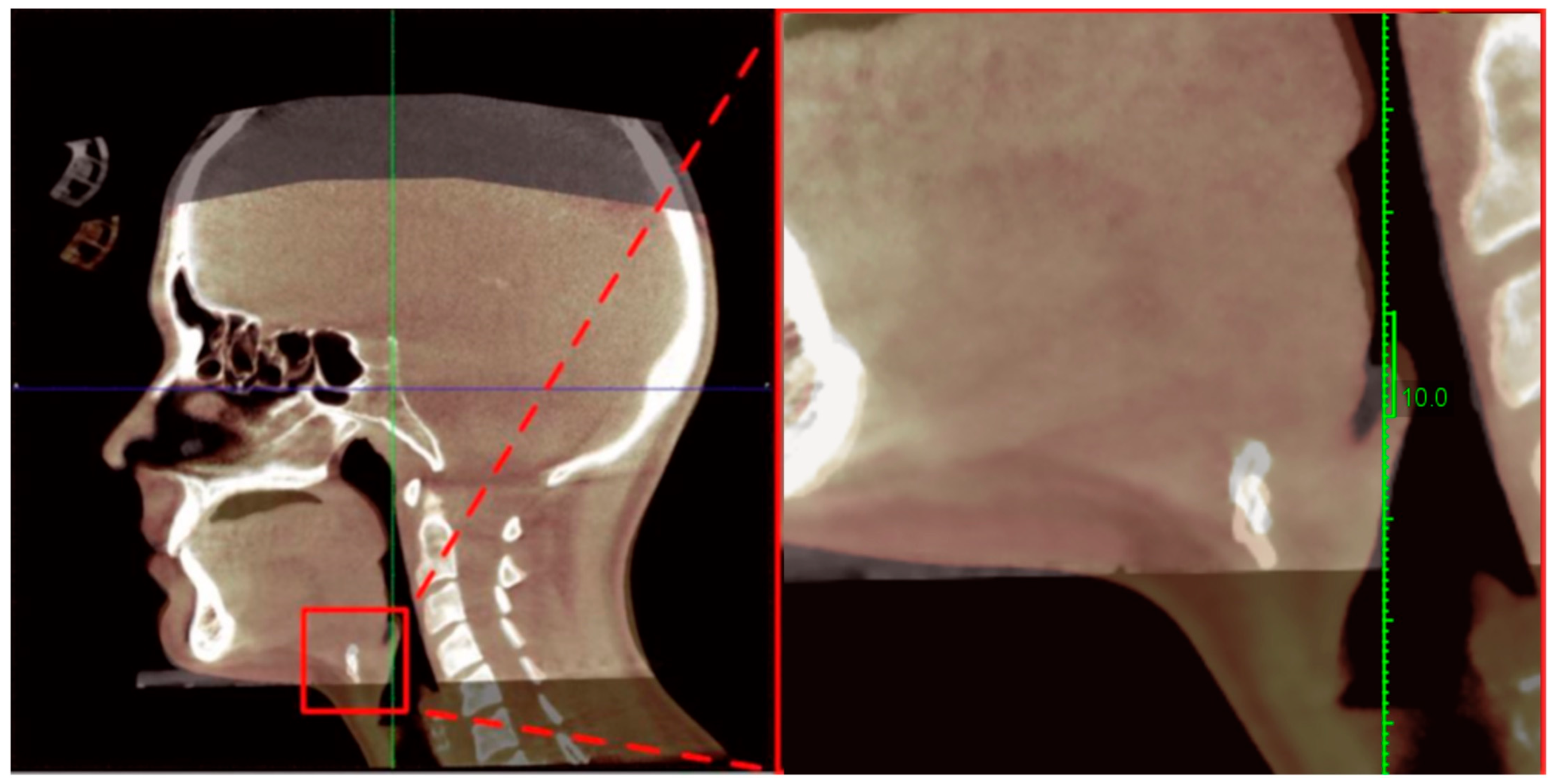

2.4.1. Cephalometric and Hyoid Imaging Outcomes (Primary Outcomes)

2.4.2. Sleep Study Outcomes (Secondary Outcomes)

2.5. Intervention

2.5.1. Tongue Exercises

- Tongue brushing: Participants brushed the top and sides of the tongue while holding different positions. The movement was repeated five times per session.

- Tongue sliding: Participants placed the tongue tip against the hard palate just posterior to the maxillary incisors and slid it posteriorly along the palate. This movement was repeated 20 times per session.

- Tongue suction: Participants pressed the entire dorsum of the tongue firmly against the hard palate and maintained the contraction for 1 s before relaxing. The protocol also included sustained 10 s holds. Each participant completed 20 short-duration holds and 20 long-duration holds per session

- Tongue depression: Participants maintained tongue tip contact with the mandibular incisors while pressing the posterior tongue downward toward the mouth floor. This exercise was repeated 20 times per session.

2.5.2. Soft Palate Exercises

- Palatal elevation: Participants elevated the soft palate and uvula while phonating “ah,” alternating between short (approximately 1 s) and long “a-a-a” (approximately 5 s) vocalizations. This exercise was performed 20 times per session.

- Balloon inflation: Participants inhaled nasally and exhaled forcefully into a balloon five consecutive times without removing it from the mouth. This sequence was completed three times per session. If a balloon was unavailable, participants performed steady exhalation through pursed lips as an alternative.

2.5.3. Facial Exercises

- Cheek resistance: Participants placed one finger intraorally against the buccal mucosa and contracted the cheek muscles outward against manual resistance. This exercise was performed 10 times per side per session. When intraoral finger placement was not socially feasible during the daytime, the exercise was performed in the morning and evening only

- Air pumping: Participants inflated one cheek with air while maintaining lip seal and then transferred the air from one cheek to the other. This action was repeated 10 times per side per session

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Within-Group Changes in Sleep and Hyoid Measurements

3.2. Between-Group Comparisons of Sleep and Hyoid Position Changes

3.3. Correlations Between Changes in Hyoid Position and Sleep Parameters

3.4. Correlations Between Changes in Sleep Parameters and Hyoid Morphometry

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Definitions of Cephalometric Landmarks Used in Hyoid and Craniofacial Analysis

| Acronym | Landmark/Full Term | Definition |

| N | Nasion | The most anterior point of the fron–nasal suture. |

| S | Sella | The midpoint of the sella turcica. |

| Po | Porion | The uppermost point on the external auditory meatus. |

| Or | Orbitale | The lowest point on the inferior margin of the orbit. |

| Co | Condylion | The most superior point on the mandibular condyle. |

| Ar | Articulare | The intersection of the posterior border of the mandibular ramus and the cranial base. |

| Ba | Basion | The most inferior point on the anterior margin of the foramen magnum. |

| ANS | Anterior Nasal Spine | The tip of the anterior nasal spine. |

| PNS | Posterior Nasal Spine | The most posterior point on the hard palate. |

| A | Point A (Subspinale) | The deepest midline point between the anterior nasal spine and the maxillary alveolar crest. |

| B | Point B (Supramentale) | The deepest midline point between the alveolar crest and the chin on the mandibular contour. |

| Pog | Pogonion | The most anterior point on the bony chin. |

| Gn | Gnathion | The most anterior–inferior point on the mandibular symphysis. |

| Me | Menton | The lowest point on the mandibular symphysis. |

| RGN | Retrognathion | The most posterior–inferior point on the bony chin. |

| Go1/Go2 | Gonion (Upper/Lower) | Reference points at the posterior–inferior angle of the mandible used for angular measurements. |

| H | Hyoidale | The most superior and anterior point on the body of the hyoid bone. |

| Phw | Posterior Pharyngeal Wall | The posterior wall of the pharynx at the oropharyngeal level. |

| aiC2, aiC3, aiC4 | Anterior–Inferior Points of Cervical Vertebrae C2–C4 | The most inferior–anterior points of the respective cervical vertebral bodies. |

| asC3 | Anterior–Superior Point of C3 | The most superior–anterior point on the C3 vertebral body. |

Appendix B. Hyoid Musculature: Anatomy and Functional Roles Relevant—Upper Airway Physiology

| Muscle Group/Muscle | Primary Actions | Relevance—Swallowing, Speech, and Upper Airway Physiology |

| Suprahyoid muscles | ||

| Digastric (anterior and posterior bellies) | Elevates hyoid with fixed mandible; depresses mandible with fixed hyoid; contributes—mouth opening and lateral grinding | Assists oral floor elevation during swallowing; influences mandibular and –ngue positioning affecting oropharyngeal airway space |

| Stylohyoid | Elevates and retracts hyoid; elongates oral floor | Supports tongue elevation and coordinated bolus transit; contributes—upper airway stabilization |

| Mylohyoid | Elevates hyoid and oral floor with fixed mandible; depresses mandible with fixed hyoid; contributes—lateral grinding | Facilitates oral-phase swallowing and phonation; elevates hyoid and tongue base to help maintain airway patency |

| Geniohyoid | Elevates and anteriorly displaces hyoid; widens airway; assists grinding | Enhances airway patency through anterior hyoid movement; important in swallow initiation and upper airway stabilization |

| Infrahyoid muscles | ||

| Omohyoid (superior and inferior bellies) | Depresses and stabilizes hyoid; tenses cervical fascia; maintains internal jugular vein patency | Stabilizes hyoid during respiration; coordinates hyoid–laryngeal motion impacting airway diameter |

| Sternohyoid | Depresses and stabilizes hyoid during mandibular movements | Helps maintain lower hyoid position, influencing tongue base posture and airway configuration |

| Sternothyroid | Depresses and stabilizes larynx during phonation | Modulates laryngeal height, airflow characteristics, and airway resistance |

| Thyrohyoid | Elevates larynx with fixed hyoid; depresses hyoid with fixed larynx | Coordinates laryngeal elevation during swallowing; influences upper airway aperture during phonation and respiration |

References

- Kayamori, F.; Rabelo, F.A.W.; Nazario, D.; Thuller, E.R.; Bianchini, E.M.G. Myofunctional assessment for obstructive sleep apnea and the association with patterns of upper airway collapse: A preliminary study. Sleep Sci. 2022, 15, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepnowsky, C.J.; Moore, P.J. Nasal CPAP treatment for obstructive sleep apnea: Developing a new perspective on dosing strategies and compliance. J. Psychosom. Res. 2003, 54, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, K.C.; Drager, L.F.; Genta, P.R.; Marcondes, B.F.; Lorenzi-Filhoy, G. Effects of oropharyngeal exercises on patients with moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 179, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ieto, V.; Kayamori, F.; Montes, M.I.; Hirata, R.P.; Gregório, M.G.; Alencar, A.M.; Drager, L.F.; Genta, P.R.; Lorenzi-Filho, G. Effects of oropharyngeal exercises on snoring: A randomized trial. Chest 2015, 148, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felício, C.M.; Dias FVda, S.; Trawitzki, L.V.V. Obstructive sleep apnea: Focus on myofunctional therapy. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2018, 10, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, E.S.; Kim, H.; Huynh, P.; Jiang, N. Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Certal, V.; Abdullatif, J.; Zaghi, S.; Ruoff, C.M.; Capasso, R.; Kushida, C.A. Myofunctional therapy to treat obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep 2015, 38, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, E.; Buttafava, L.; Guida, S.; Castellini, G.; Bargeri, S.; Gianola, S. Myofunctional Therapy in Adults and Children with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An Overview and Re-Analysis of Systematic Reviews. J. Sleep Res. 2025, e70219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, B.U.; Mew, J. Hyoid slump hypothesis: A rational approach to understanding obstructive sleep apnea and related airway disorders. Med. Hypotheses 2025, 201, 111709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.H.; Park, J.W.; Jang, J.H.; Chung, J.W. Hyoid bone position as an indicator of severe obstructive sleep apnea. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubos-Strøm, H.; Hansen, D.D.; Feng, X.; Mäkinen, H.; Tinbod, U.; Köster, A.; Vaher, H.; Klungsøyr, O.; Saavedra, J.M.; Skirbekk, H.; et al. Effect of Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy with Auto-Monitoring on the Apnea–Hypopnea Index and Secondary Outcomes in Treatment-Naïve Patients with Mild to Moderate Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OMTaOSA): A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. Int. J. Orofac. Myol. Myofunctional Ther. 2025, 51, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.D.; Tinbod, U.; Feng, X.; Dammen, T.; Hrubos-Strøm, H.; Skirbekk, H. Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy for Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea—A Mixed Methods Study of Facilitators and Barriers to Treatment Adherence. Int. J. Orofac. Myol. Myofunctional Ther. 2025, 51, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Evaluation of measurement error 2: Dahlberg’s error, Bland-Altman method, and Kappa coefficient. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Izumi, S.; Hata, Y.; Tsuji, M.; Morota, K.; Hata, A.; Kobayashi, K. Effect of 10-minute oropharyngeal exercise on the apnoea–hypopnoea index. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanellari, O.; Toti, C.; Baruti Papa, E.; Ghanim, S.; Savin, C.; Romanec, C.; Romanec, C.; Balcoș, C.; Zetu, I.N. The Link between Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and Cephalometric Assessment of Upper Airways and Hyoid Bone Position. Medicina 2022, 58, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, L.; Hong, H. Upper airway and hyoid bone-related morphological parameters associated with the apnea-hypopnea index and lowest nocturnal oxygen saturation: A cephalometric analysis. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanco, S.R.P.F.; Duarte, B.B.; Almeida, A.R.; Mendonça, J.A. Cephalometric Evaluation in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea undergoing Lateral Pharyngoplasty. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 28, e278–e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmouz, S.; Calzadilla, N.; Choudhary, A.; McGinn, L.S.; Seaman, A.; Purnell, C.A. Radiographic findings predictive of obstructive sleep apnea in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 53, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbarzin, A.; Sands, S.A.; Stone, K.L.; Taranto-Montemurro, L.; Messineo, L.; Terrill, P.I.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Ensrud, K.; Purcell, S.; White, D.P.; et al. The hypoxic burden of sleep apnoea predicts cardiovascular disease-related mortality: The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study and the Sleep Heart Health Study. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, D.J.; Malhotra, A. Pathophysiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008, 5, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biben, V.; Dewi, F.; Ratunanda, S.S.; Lailiyya, N.; Nurarifah, S.A.H.; Alviani, N.F. Myofunctional Therapy and Its Effects on Retropalatal Narrowing and Snoring: A Preliminary Analysis of Rehabilitative Approaches. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 22, 3371–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poncin, W.; Willemsens, A.; Gely, L.; Contal, O. Assessment and rehabilitation of tongue motor skills with myofunctional therapy in obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2024, 20, 1535–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, L.; Comyn, F.L.; Mitra, N.; Reilly, M.P.; Wan, F.; Maislin, G.; Chmiewski, L.; Thorne-FitzGerald, M.D.; Victor, U.N.; Pack, A.I.; et al. Identification of craniofacial risk factors for obstructive sleep apnoea using three-dimensional MRI. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, D.; Amatoury, J. Influence of natural hyoid bone position and surgical repositioning on upper airway patency: A computational finite element modeling study. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 137, 1614–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartfield, P.J.; Janczy, J.; Sharma, A.; Newsome, H.A.; Sparapani, R.A.; Rhee, J.S.; Woodson, B.T.; Garcia, G.J. Anatomical determinants of upper airway collapsibility in obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2023, 68, 101741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattiyawittayakun, L. Mandibular plane to hyoid in lateral cephalometry as a predictive parameter for severity of obstructive sleep apnea. Chulalongkorn Med. J. 2024, 67, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, M.P.; Rizzoli, A.; Rabasco, J.; Vitelli, O.; Pietropaoli, N.; Cecili, M.; Marino, A.; Malagola, C. Rapid maxillary expansion outcomes in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Llatas, M.; O’connor-Reina, C.; Calvo-Henríquez, C. The role of myofunctional therapy in treating sleep-disordered breathing: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, M.H.; Thuler, E.; Triantafillou, V.; Seay, E.; Sehgal, C.; Schultz, S.; Keenan, B.T.; Schwartz, A.R.; Dedhia, R.C. Physiologic and anatomic determinants of hyoid motion during drug-induced sleep endoscopy. Sleep Breath. 2024, 28, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Capacho, E.E.; Bossa, C.P.D.; Campos, M.D.C.; Rincon-Yanez, D.; Rangel-Navia, H.; Bianchini, E.M.G. Telemedicine-supported structured Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy model for Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Patients’ report outcomes measurements. Respir. Med. 2025, 249, 108460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Therapy (n = 9) | Waiting List (n = 4) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 45.0 (38.0–52.0) | 48.5 (42.0–55.0) | 0.45 |

| Male, n (%) | 7 (77.8%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0.999 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.4 (21.9–28.9) | 24.4 (22.2–26.4) | 0.441 |

| Neck circumference, cm | 37.5 (35.5–42.5) | 35.5 (32.0–40.9) | 0.276 |

| Sleep parameters | |||

| AHI, events/h | 15.1 (10.1–17.9) | 11.2 (5.0–17.8) | 0.767 |

| ODI, events/h | 6.8 (4.6–10.3) | 8.8 (2.5–14.9) | 0.314 |

| SpO2, % | 94.9 (94.0–95.3) | 94.4 (93.3–94.8) | 0.515 |

| AHI severity, n (%) | |||

| Mild (5–14.9) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.39 |

| Moderate (15–29.9) | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (50.0%) | |

| Severe (≥30) | 5 (55.6%) | 1 (25.0%) | |

| Core hyoid measurements | |||

| Hlpaw, mm | 9.6 (8.1–12.3) | 8.5 (4.9–14.4) | 0.123 |

| MPH, mm | 19.8 (18.7–21.9) | 12.8 (11.7–24.1) | 0.515 |

| HRGN, mm | 37.5 (32.0–39.3) | 37.5 (29.1–44.3) | 0.515 |

| C3H, mm | 36.9 (34.2–39.8) | 34.7 (28.2–42.3) | 0.575 |

| HC3Me, mm | 9.4 (6.6–12.7) | 2.5 (3.9–7.2) | 0.953 |

| Variable | Baseline (TG) | Post (TG) | Change (TG) | p (TG) | Baseline (WL) | Post (WL) | Change (WL) | p (WL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI, events/h | 15.1 (10.1–17.9) | 13.9 (8.0–17.1) | −1.2 (−3.5–0.8) | 0.296 | 11.2 (5.0–17.8) | 13.8 (3.8–25.2) | +2.9 (−0.5–7.5) | 0.422 |

| ODI, events/h | 6.8 (4.6–10.3) | 8.0 (4.1–11.8) | +0.9 (−0.6–2.2) | 0.314 | 8.8 (2.5–14.9) | 7.7 (1.5–18.0) | +0.3 (−1.5–1.8) | 0.463 |

| SpO2, % | 94.9 (94.0–95.3) | 94.8 (93.8–95.1) | −0.05 (−0.30–0.20) | 0.515 | 94.4 (93.3–94.8) | 93.7 (93.4–94.9) | −0.14 (−0.50–0.30) | 0.600 |

| Hlpaw, mm | 9.6 (8.1–12.3) | 10.4 (7.3–14.3) | +0.8 (−0.3–2.0) | 0.123 | 8.5 (4.9–14.4) | 10.0 (7.5–12.2) | +0.6 (−1.2–4.6) | 0.208 |

| MPH, mm | 19.8 (18.7–21.9) | 19.9 (17.5–22.8) | +0.3 (−0.7–1.5) | 0.515 | 12.8 (11.7–24.1) | 13.1 (11.5–22.8) | −0.4 (−1.0–0.5) | 0.701 |

| HRGN, mm | 37.5 (32.0–39.3) | 37.5 (33.2–39.0) | −0.2 (−1.5–1.3) | 0.515 | 37.5 (29.1–44.3) | 35.4 (25.0–38.1) | −4.2 (−7.2–1.1) | 0.075 |

| C3H, mm | 36.9 (34.2–39.8) | 37.0 (34.3–38.8) | +0.4 (−0.8–1.6) | 0.575 | 34.7 (28.2–42.3) | 35.3 (29.3–41.2) | +0.2 (−1.4–1.8) | 0.583 |

| HC3Me, mm | 9.4 (6.6–12.7) | 8.4 (6.2–12.4) | −0.1 (−1.2–1.0) | 0.953 | 2.5 (−3.9–7.2) | 6.7 (−4.0–10.7) | +2.6 (−0.5–5.4) | 0.382 |

| Variable | Therapy Group Change (n = 9) | Waiting List Change (n = 4) | U | p-Value | r | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep parameters | ||||||

| ΔAHI, events/h | −1.2 (−3.5–0.8) | +2.9 (−0.5–7.5) | 12.0 | 0.767 | −0.08 | No significant difference |

| ΔODI, events/h | +0.9 (−0.6–2.2) | +0.3 (−1.5–1.8) | 15.0 | 0.314 | −0.28 | No significant difference |

| ΔSpO2, % | −0.05 (−0.30–0.20) | −0.14 (−0.50–0.30) | 15.0 | 0.515 | −0.18 | No significant difference |

| Hyoid position | ||||||

| ΔHlpaw, mm | +0.8 (−0.3–2.0) | +0.6 (−1.2–4.6) | 13.0 | 0.123 | −0.43 | No significant difference |

| ΔMPH, mm | +0.3 (−0.7–1.5) | −0.4 (−1.0–0.5) | 14.0 | 0.515 | −0.18 | No significant difference |

| ΔHRGN, mm | −0.2 (−1.5–1.3) | −4.2 (−7.2–1.1) | 4.0 | 0.031 | −0.60 | Large effect; WL decreased more |

| ΔC3H, mm | +0.4 (−0.8–1.6) | +0.2 (−1.4–1.8) | 16.0 | 0.575 | −0.16 | No significant difference |

| ΔHC3Me, mm | −0.1 (−1.2–1.0) | +2.6 (−0.5–5.4) | 11.0 | 0.090 | −0.47 | Moderate effect; trend |

| Significant additional changes | ||||||

| ΔAngleGnGo2H, ° | −0.2 (−2.0–1.8) | −4.8 (−13.9–3.4) | 8.0 | 0.090 | −0.47 | Moderate effect; trend |

| ΔHRgn1_A, mm | −0.3 (−1.2–0.6) | −2.3 (−4.8–0.0) | 5.0 | 0.031 | −0.60 | Large effect; WL decreased more |

| ΔHGo1, mm | +0.5 (−1.0–2.2) | +7.9 (2.0–13.0) | 3.0 | 0.045 | −0.56 | Large effect; WL increased more |

| ΔHGo2, mm | −1.6 (−3.5–0.8) | +7.9 (3.1–12.7) | 1.0 | 0.017 | −0.66 | Large effect; WL increased more |

| ΔHMe, mm | +0.2 (−2.5–2.9) | −4.2 (−8.8–0.4) | 2.5 | 0.063 | −0.52 | Moderate effect; trend |

| ΔAngleBMeHy, ° | +0.9 (−1.5–3.2) | +4.1 (1.5–6.8) | 2.5 | 0.064 | −0.51 | Moderate effect; trend |

| Variable | ΔAHI τ | p | ΔODI τ | p | ΔSpO2 τ | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔHlpaw | −0.36 | 0.088 | −0.10 | 0.625 | 0.21 | 0.329 |

| ΔMPH | 0.41 | 0.051 | 0.26 | 0.222 | −0.15 | 0.464 |

| ΔHMPMeGo1Perp | 0.41 | 0.057 | 0.22 | 0.297 | −0.22 | 0.297 |

| ΔHMP2MeGo2Perp | 0.50 | 0.017 | 0.25 | 0.246 | −0.30 | 0.160 |

| ΔHGo1Gn | 0.41 | 0.051 | 0.26 | 0.222 | −0.26 | 0.222 |

| ΔHGo2Gn | 0.48 | 0.024 | 0.17 | 0.427 | −0.40 | 0.058 |

| ΔHMeasC3withhelper | 0.28 | 0.180 | 0.23 | 0.272 | −0.44 | 0.038 |

| ΔHna | 0.45 | 0.032 | −0.12 | 0.582 | 0.07 | 0.760 |

| ΔHApoint | 0.28 | 0.180 | 0.03 | 0.903 | −0.08 | 0.714 |

| ΔHRgn1_A | 0.22 | 0.299 | 0.12 | 0.582 | −0.07 | 0.760 |

| ΔHPhw | 0.00 | 0.999 | 0.21 | 0.329 | −0.46 | 0.028 |

| ΔAngleGnGo2H | 0.36 | 0.088 | 0.26 | 0.222 | −0.31 | 0.143 |

| Variable | ΔAHI τ | p | ΔODI τ | p | ΔSpO2 τ | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔHlpaw | −0.61 | 0.022 | −0.06 | 0.835 | 0.39 | 0.144 |

| ΔMPH | 0.72 | 0.007 | 0.06 | 0.835 | −0.06 | 0.835 |

| ΔHMPMeGo1Perp | 0.56 | 0.037 | 0.11 | 0.677 | −0.33 | 0.211 |

| ΔHMP2MeGo2Perp | 0.59 | 0.028 | 0.03 | 0.917 | −0.37 | 0.173 |

| ΔHGo1Gn | 0.61 | 0.022 | 0.06 | 0.835 | −0.28 | 0.297 |

| ΔHGo2Gn | 0.67 | 0.012 | 0.00 | 0.999 | −0.44 | 0.095 |

| ΔHMeasC3withhelper | 0.61 | 0.022 | 0.06 | 0.835 | −0.39 | 0.144 |

| ΔHna | 0.72 | 0.007 | −0.06 | 0.835 | −0.17 | 0.532 |

| ΔHApoint | 0.56 | 0.037 | 0.00 | 0.999 | −0.33 | 0.211 |

| ΔHRgn1_A | 0.61 | 0.022 | 0.17 | 0.532 | −0.39 | 0.144 |

| ΔHPhw | 0.06 | 0.835 | 0.06 | 0.835 | −0.61 | 0.022 |

| ΔAngleGnGo2H | 0.72 | 0.007 | 0.06 | 0.835 | −0.39 | 0.144 |

| Variable | ΔAHI τ | p | ΔODI τ | p | ΔSpO2 τ | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔHlpaw | 0.00 | 0.999 | 0.00 | 0.999 | 0.00 | 0.999 |

| ΔMPH | 0.00 | 0.999 | 0.67 | 0.174 | −0.67 | 0.174 |

| ΔHMPMeGo1Perp | 0.67 | 0.174 | 0.67 | 0.174 | −0.67 | 0.174 |

| ΔHMP2MeGo2Perp | 0.33 | 0.497 | 0.33 | 0.497 | −0.33 | 0.497 |

| ΔHGo1Gn | 0.33 | 0.497 | — | — | — | — |

| ΔHGo2Gn | 0.00 | 0.999 | 0.67 | 0.174 | −0.67 | 0.174 |

| ΔHMeasC3withhelper | 0.00 | 0.999 | 0.67 | 0.174 | −0.67 | 0.174 |

| ΔHna | 0.00 | 0.999 | −0.67 | 0.174 | 0.67 | 0.174 |

| ΔHApoint | −0.33 | 0.497 | −0.33 | 0.497 | 0.33 | 0.497 |

| ΔHRgn1_A | −0.18 | 0.718 | −0.18 | 0.718 | 0.18 | 0.718 |

| ΔHPhw | 0.00 | 0.999 | 0.67 | 0.174 | −0.67 | 0.174 |

| ΔAngleGnGo2H | 0.00 | 0.999 | 0.67 | 0.174 | −0.67 | 0.174 |

| Hyoid Parameter | Between-Group Changes | Within-Group Changes | OMT Effect Direction | Sleep Parameter Correlation in Therapy Group | Interpretation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waiting Δ | Therapy Δ | p-Value | Waiting List | Therapy Group | ΔAHI (τ) | ΔODI (τ) | |||

| ΔC3H | +0.18 | +0.36 | 0.090 † | NS | NS | ↑ Increase | −0.083 | 0.717 | Unfavorable: ↑ C3H → ↑ ODI |

| ΔHlpaw | +0.64 | +0.80 | NS | NS | NS | ↑ Increase | −0.783 | −0.133 | Favorable: ↑ Hlpaw → ↓ AHI |

| ΔMPH | −0.37 | +0.25 | NS | NS | NS | ↑ Reversal | 0.883 | 0.067 | Unfavorable: ↑ MPH → ↑ AHI |

| ΔHMPMeGo1Perp | −0.12 | +0.32 | NS | NS | NS | ↑ Reversal | 0.733 | 0.150 | Unfavorable: ↑ Distance → ↑ AHI |

| ΔHMP2MeGo2Perp | +0.45 | +0.13 | NS | NS | NS | ↑ Increase | 0.787 | −0.025 | Unfavorable: ↑ Distance → ↑ AHI |

| ΔHGo1Gn | +0.15 | +0.39 | 0.045 * | p = 0.068 † | NS | ↑ Increase | 0.750 | 0.133 | Unfavorable: ↑ HGo1Gn → ↑ AHI |

| ΔHGo2Gn | +0.88 | +0.07 | 0.017 * | p = 0.068 † | NS | ↓ Prevention | 0.783 | 0.017 | Favorable: OMT prevents ↑ HGo2Gn |

| ΔHMeasC3withhelper | −0.05 | +0.44 | NS | NS | NS | ↑ Increase | 0.817 | −0.017 | Unfavorable: ↑ Distance → ↑ AHI |

| ΔHna | +0.23 | +0.10 | NS | NS | NS | ↑ Increase | 0.883 | −0.050 | Unfavorable: ↑ Hna → ↑ AHI |

| ΔHApoint | −1.42 | +0.72 | NS | NS | NS | ↑ Reversal | 0.783 | 0.017 | Unfavorable: ↑ HApoint → ↑ AHI |

| ΔHBpoint | −3.12 | +0.33 | 0.064 † | p = 0.068 † | NS | ↑ Reversal | 0.633 † | 0.000 | Trend unfavorable |

| ΔHRgn1_A | −3.95 | +0.29 | 0.031 * | p = 0.068 † | NS | ↑ Reversal | 0.767 | 0.217 | Unfavorable: ↑ HRgn1_A → ↑ AHI |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Köster, A.; Hoang, A.D.; Dashuk, A.; Vaher, H.; Sikk, K.; Jagomägi, T. Effects of Web-Based Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy on Hyoid Bone Position in Adults with Mild to Moderate Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Evidence from an Estonian Substudy of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010257

Köster A, Hoang AD, Dashuk A, Vaher H, Sikk K, Jagomägi T. Effects of Web-Based Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy on Hyoid Bone Position in Adults with Mild to Moderate Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Evidence from an Estonian Substudy of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):257. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010257

Chicago/Turabian StyleKöster, Andres, Anh Dao Hoang, Andrey Dashuk, Heisl Vaher, Katrin Sikk, and Triin Jagomägi. 2026. "Effects of Web-Based Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy on Hyoid Bone Position in Adults with Mild to Moderate Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Evidence from an Estonian Substudy of a Randomized Controlled Trial" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010257

APA StyleKöster, A., Hoang, A. D., Dashuk, A., Vaher, H., Sikk, K., & Jagomägi, T. (2026). Effects of Web-Based Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy on Hyoid Bone Position in Adults with Mild to Moderate Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Evidence from an Estonian Substudy of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010257