Role of Chest CT Radiomics in Differentiating Tumorlets and Granulomas: A Preliminary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

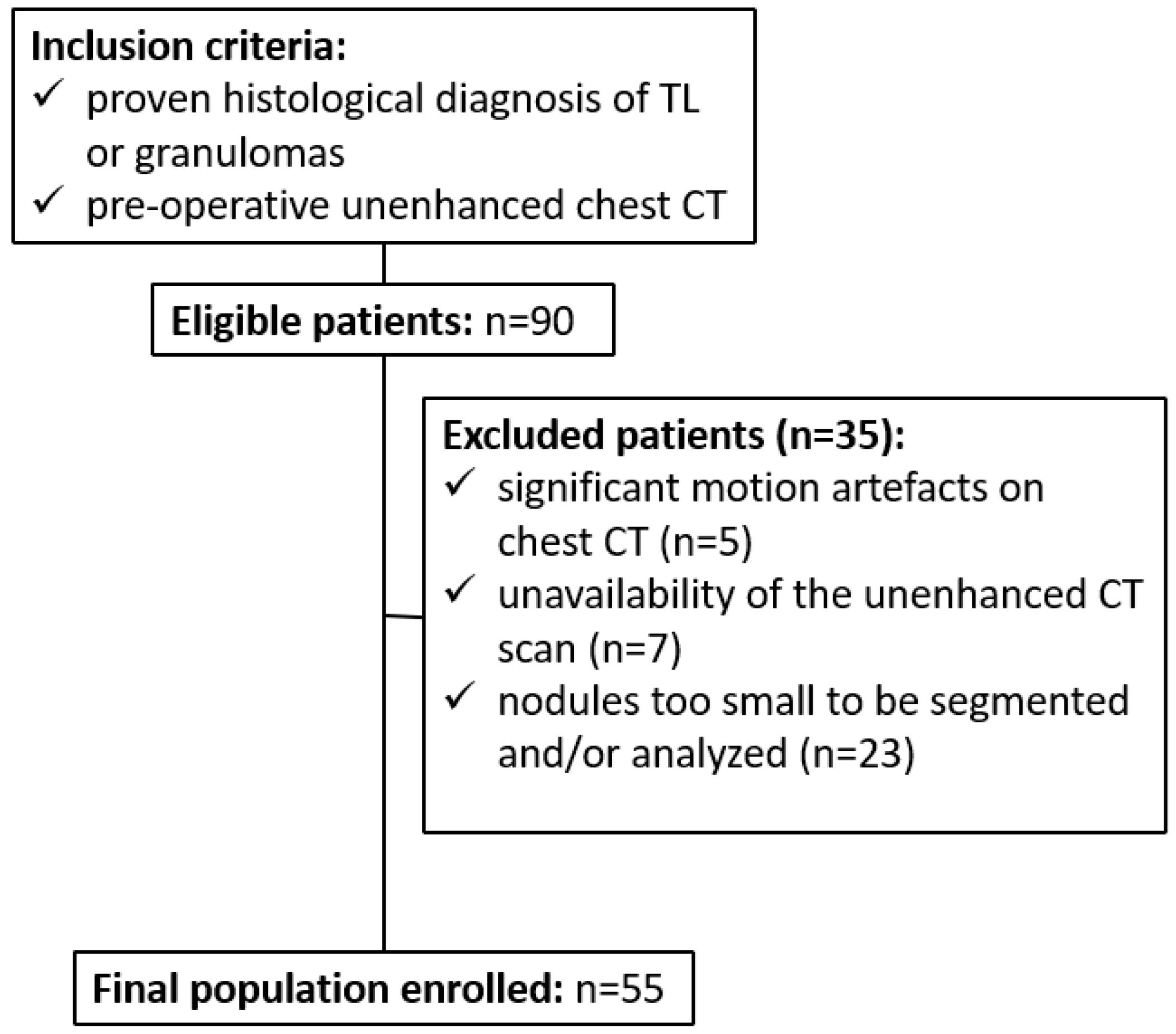

2.1. Patient Population and Study Design

2.2. CT Scan Protocol and Image Reconstruction

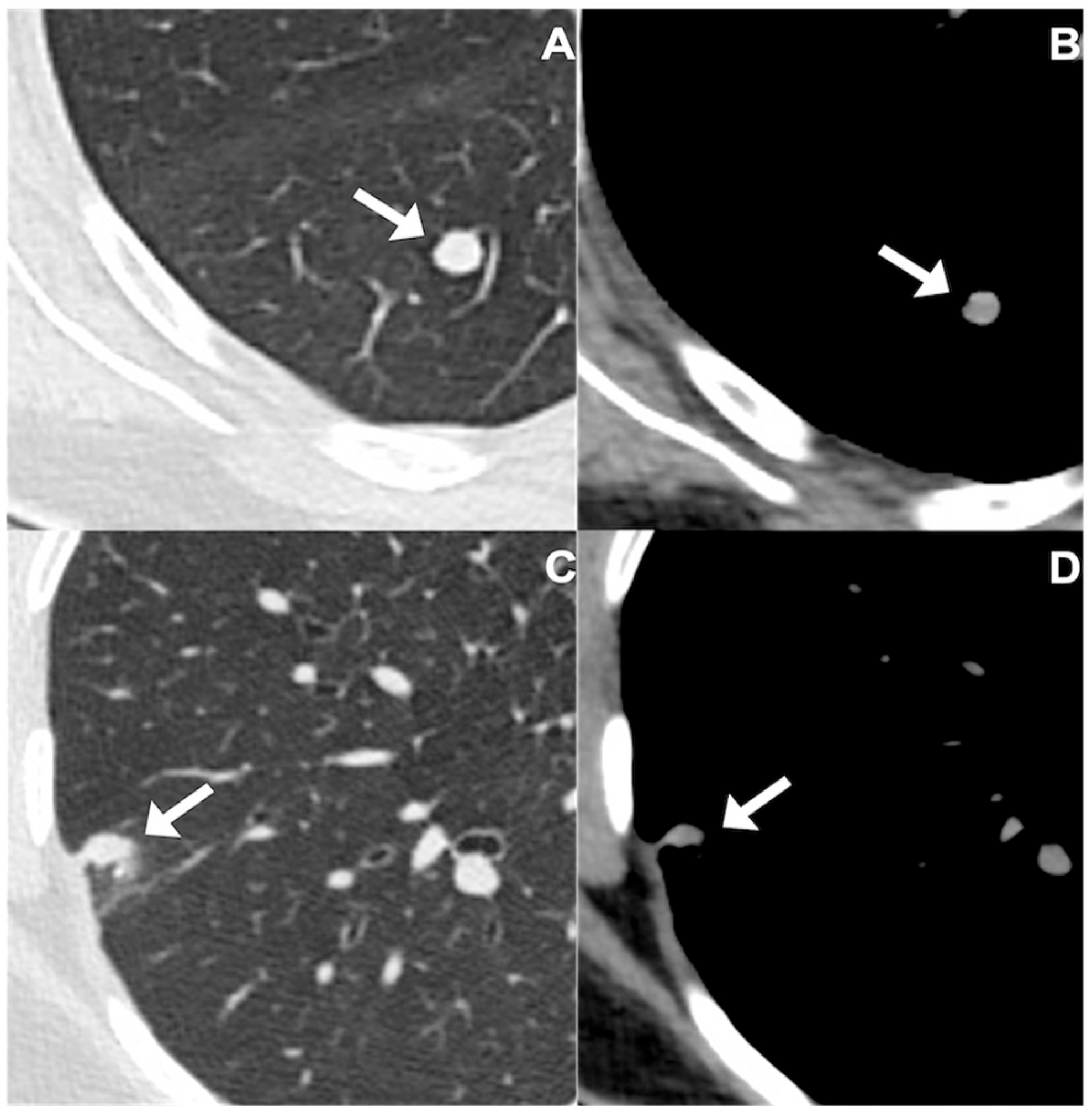

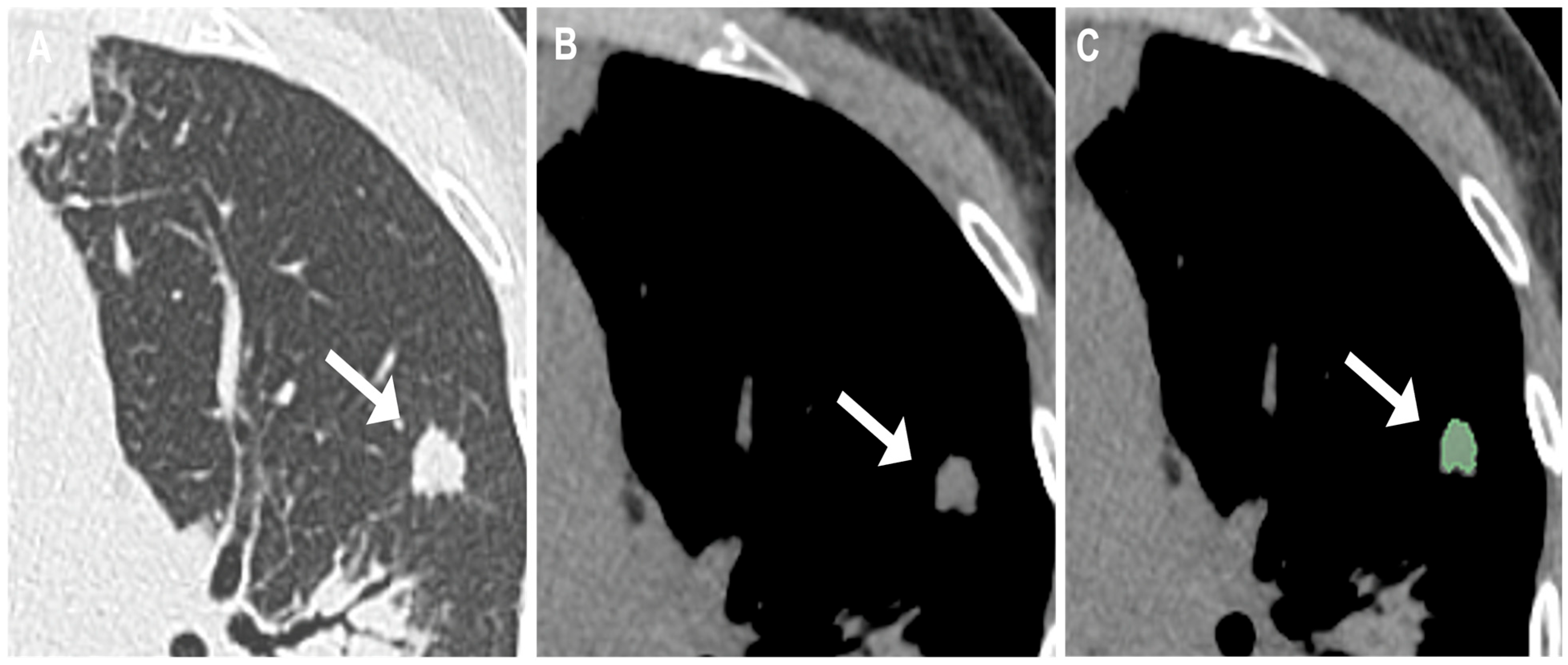

2.3. Evaluation and Segmentation of Chest CT Images

2.4. Extraction of Radiomic Features

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Cohort, Patient Characteristics, and CT Findings

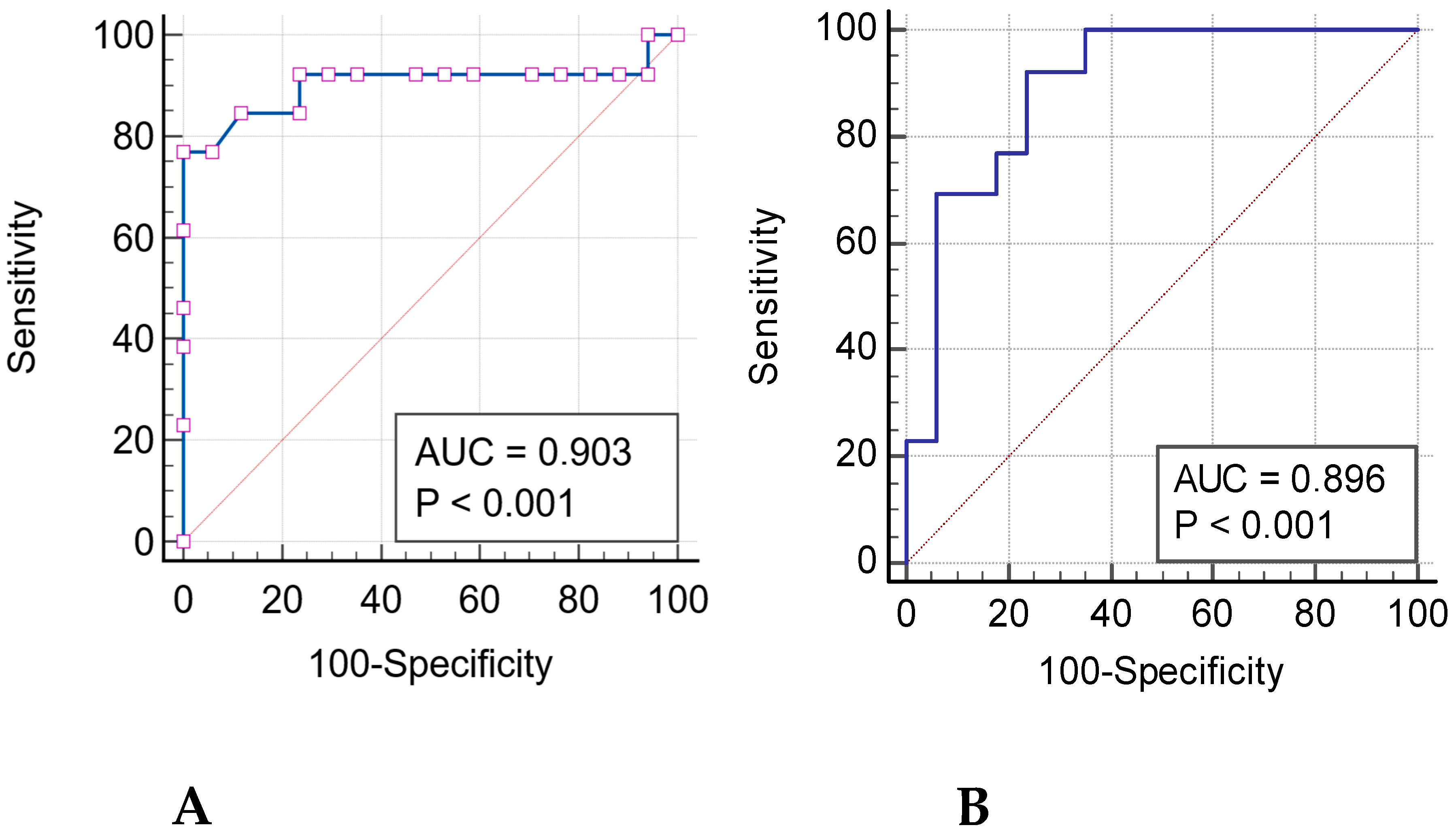

3.2. Radiomics Features and ROC Curves

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TL | Tumorlet |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| GLCM | GreyLevelCo-occurrenceMatrix |

| GLDM | GrayLevelDependenceMatrix |

| GLRLM | GreyLevelRunLengthMatrix |

| GLSZM | GrayLevelSizeZoneMatrix |

References

- MacMahon, H.; Naidich, D.P.; Goo, J.M.; Lee, K.S.; Leung, A.N.C.; Mayo, J.R.; Mehta, A.C.; Ohno, Y.; Powell, C.A.; Prokop, M.; et al. Guidelines for Management of Incidental Pulmonary Nodules Detected on CT Images: From the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology 2017, 284, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W.D.; Brambilla, E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Yatabe, Y.; Austin, J.H.M.; Beasley, M.B.; Chirieac, L.R.; Dacic, S.; Duhig, E.; Flieder, D.B.; et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, P.A.; Junker, K. Pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors in the new WHO 2015 classification: Start of breaking new grounds? Pathologe 2015, 36, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, A.; Chan, J.K.; Coindre, J.M.; Detterbeck, F.; Girard, N.; Harris, N.L.; Jaffe, E.S.; Kurrer, M.O.; Marom, E.M.; Moreira, A.L.; et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Thymus: Continuity and Changes. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 1383–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.Y.; Hwang, G.; Pancirer, D.; Hornbacker, K.; Codima, A.; Lui, N.S.; Raj, R.; Kunz, P.; Padda, S.K. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: Clinical characteristics and progression to carcinoid tumour. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 59, 2101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranchod, M. The histogenesis and development of pulmonary tumorlets. Cancer 1977, 39, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, C.W.; Baliff, J.P.; Torigian, D.A.; Litzky, L.A.; Gefter, W.B.; Akers, S.R. Spectrum of pulmonary neuroendocrine cell proliferation: Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia, tumorlet, and carcinoids. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 195, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Thoracic Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer, Ed.; World Health Organization: Lyon, France, 2021; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Thattaamuriyil Padmakumari, L.; Guido, G.; Caruso, D.; Nacci, I.; Del Gaudio, A.; Zerunian, M.; Polici, M.; Gopalakrishnan, R.; Sayed Mohamed, A.K.; De Santis, D.; et al. The Role of Chest CT Radiomics in Diagnosis of Lung Cancer or Tuberculosis: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, D.; Polici, M.; Zerunian, M.; Pucciarelli, F.; Guido, G.; Polidori, T.; Landolfi, F.; Nicolai, M.; Lucertini, E.; Tarallo, M. Radiomics in oncology, part 1: Technical principles and gastrointestinal application in CT and MRI. Cancers 2021, 13, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, D.; Polici, M.; Zerunian, M.; Pucciarelli, F.; Guido, G.; Polidori, T.; Landolfi, F.; Nicolai, M.; Lucertini, E.; Tarallo, M. Radiomics in oncology, part 2: Thoracic, genito-urinary, breast, neurological, hematologic and musculoskeletal applications. Cancers 2021, 13, 2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangir, A.K.; Orhan, K.; Kahya, Y.; Uğurum Yücemen, A.; Aktürk, İ.; Ozakinci, H.; Gursoy Coruh, A.; Dizbay Sak, S. A CT-Based Radiomic Signature for the Differentiation of Pulmonary Hamartomas from Carcinoid Tumors. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuillier, P.; Liberini, V.; Rampado, O.; Gallio, E.; De Santi, B.; Ceci, F.; Metovic, J.; Papotti, M.; Volante, M.; Molinari, F.; et al. Diagnostic Value of Conventional PET Parameters and Radiomic Features Extracted from 18F-FDG-PET/CT for Histologic Subtype Classification and Characterization of Lung Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 1979, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi, D.; Bicci, E.; Cavigli, E.; Danti, G.; Bettarini, S.; Tortoli, P.; Mazzoni, L.N.; Busoni, S.; Pradella, S.; Miele, V. Radiomics in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumours (NETs). Radiol. Med. 2022, 127, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Oh, J.H.; Riyahi, S.; Liu, C.J.; Jiang, F.; Chen, W.; White, C.; Rimner, A.; Mechalakos, J.G.; Deasy, J.O.; et al. Radiomics analysis of pulmonary nodules in low-dose CT for early detection of lung cancer. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 1537–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.D.; Kanne, J.P.; Broderick, L.S.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Meyer, C.A. Lung-RADS: Pushing the Limits. Radiographics 2017, 37, 1975–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beig, N.; Khorrami, M.; Alilou, M.; Prasanna, P.; Braman, N.; Orooji, M.; Rakshit, S.; Bera, K.; Rajiah, P.; Ginsberg, J.; et al. Perinodular and Intranodular Radiomic Features on Lung CT Images Distinguish Adenocarcinomas from Granulomas. Radiology 2019, 290, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorrami, M.; Bera, K.; Thawani, R.; Rajiah, P.; Gupta, A.; Fu, P.; Linden, P.; Pennell, N.; Jacono, F.; Gilkeson, R.C.; et al. Distinguishing granulomas from adenocarcinomas by integrating stable and discriminating radiomic features on non-contrast computed tomography scans. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, L.; Lu, Y.; Xue, F. Preoperative diagnosis of malignant pulmonary nodules in lung cancer screening with a radiomics nomogram. Cancer Commun. 2020, 40, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binczyk, F.; Prazuch, W.; Bozek, P.; Polanska, J. Radiomics and artificial intelligence in lung cancer screening. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1186–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, S.; Simon, R. Bias in error estimation when using cross-validation for model selection. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient Data | Total Patients (n = 55) | Tumorlets Group (n = 32) | Granulomas Group (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 64 ± 14.6 | 68 ± 10.2 | 58 ± 17.7 |

| Years (range) | 24–84 | 43–80 | 24–84 |

| Male-to-female ratio | 17–38 (31%) | 6–26 (19%) | 11–12 (48%) |

| Smokers | 24 (44%) | 12 (38%) | 12 (52%) |

| Comorbidities | 38 (69%) | 26 (81%) | 12 (52%) |

| Previous neoplasm | 17 (31%) | 7 (22%) | 10 (43%) |

| Nodules CT Findings | Total Patients (n = 55) | Tumorlets Group (n = 32) | Granulomas Group (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular margins | 35 (64%) | 25 (78%) | 10 (43%) |

| Irregular margins | 20 (36%) | 7 (22%) | 13 (57%) |

| Spiculations | 17 (31%) | 2 (6%) | 15 (65%) |

| Location | |||

| LLL | 13 (24%) | 11 (34%) | 2 (9%) |

| LUL | 11 (20%) | 6 (19%) | 5 (22%) |

| RUL | 11 (20%) | 7 (22%) | 4 (17%) |

| RLL | 11 (20%) | 5 (16%) | 6 (26%) |

| Radiomics Features | TL vs. Granulomas | ROC CURVE ANALYSIS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAPE | p Value | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | p Value |

| Flatness | <0.001 | 76.92 | 100 | 0.903 | <0.001 |

| Least Axis Length | <0.001 | 64.71 | 84.62 | 0.721 | 0.003 |

| Surface Volume Ratio | <0.001 | 76.92 | 88.24 | 0.894 | <0.001 |

| FIRST ORDER | |||||

| Range | <0.001 | 84.62 | 82.35 | 0.864 | <0.001 |

| GLCM | |||||

| Joint Average | <0.001 | 92.31 | 70.59 | 0.828 | <0.001 |

| Sum Average | <0.001 | 84.62 | 76.47 | 0.846 | <0.001 |

| GLDM | |||||

| Dependence Non Uniformity | <0.001 | 84.62 | 82.35 | 0.894 | <0.001 |

| High Gray Level Emphasis | <0.001 | 92.31 | 76.47 | 0.869 | <0.001 |

| GRLRM | |||||

| High Gray Level Run Emphasis | <0.001 | 92.31 | 76.47 | 0.869 | <0.001 |

| Long Run High Gray Level Emphasis | <0.001 | 92.31 | 76.47 | 0.896 | <0.001 |

| Run Entropy | <0.001 | 100 | 64.71 | 0.885 | <0.001 |

| Short Run High Gray Level Emphasis | <0.001 | 92.31 | 76.47 | 0.869 | <0.001 |

| GLSZM | |||||

| High Gray Level Zone Emphasis | <0.001 | 92.31 | 82.35 | 0.878 | <0.001 |

| Low Gray Level Zone Emphasis | <0.001 | 76.92 | 88.24 | 0.894 | <0.001 |

| Small Area High Gray Level Emphasis | <0.001 | 92.31 | 82.35 | 0.878 | <0.001 |

| Small Area Low Gray Level Emphasis | <0.001 | 92.31 | 70.59 | 0.898 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Siciliani, A.; Guido, G.; De Santis, D.; Bracci, B.; Masci, B.; Faggiano, A.; Mikovic, N.; Paravani, P.; Martiradonna, M.; Palmeri, F.; et al. Role of Chest CT Radiomics in Differentiating Tumorlets and Granulomas: A Preliminary Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010210

Siciliani A, Guido G, De Santis D, Bracci B, Masci B, Faggiano A, Mikovic N, Paravani P, Martiradonna M, Palmeri F, et al. Role of Chest CT Radiomics in Differentiating Tumorlets and Granulomas: A Preliminary Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010210

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiciliani, Alessandra, Gisella Guido, Domenico De Santis, Benedetta Bracci, Benedetta Masci, Antongiulio Faggiano, Nevena Mikovic, Piero Paravani, Maurizio Martiradonna, Federica Palmeri, and et al. 2026. "Role of Chest CT Radiomics in Differentiating Tumorlets and Granulomas: A Preliminary Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010210

APA StyleSiciliani, A., Guido, G., De Santis, D., Bracci, B., Masci, B., Faggiano, A., Mikovic, N., Paravani, P., Martiradonna, M., Palmeri, F., De Dominicis, C., Mancini, M., Zerunian, M., Trabalza Marinucci, B., Maurizi, G., Rendina, E. A., Francone, M., Laghi, A., Ibrahim, M., & Caruso, D. (2026). Role of Chest CT Radiomics in Differentiating Tumorlets and Granulomas: A Preliminary Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010210