Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays in the Management of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: A Clinical Update

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays

4. Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy

4.1. Epidemiology and Clinical Landscape

4.2. Physiopathology: From Tissue Injury to Hemostatic Derangements

4.3. Diagnosis

5. Clinical Phenotypes

5.1. Hypocoagulability and Hypercoagulability

5.2. Hypofibrinogenemia

5.3. Fibrinolysis Derangements

5.4. Platelet Dysfunction

6. Stepwise Interpretation of Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays for Goal-Directed Therapy

6.1. Prolonged R/CT

6.2. Low MA/MCF with Normal Fibrinogen Contribution

6.3. Low MA/MCF with Reduced Fibrinogen Contribution

6.4. Hyperfibrinolysis and Fibrinolysis Shutdown

6.5. High Clot Amplitude

6.6. Platelet Function Testing

7. Hemostatic Resuscitation: The Place for Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays

7.1. Current Evidence

7.2. Guidelines and Clinical Practice

7.3. Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kleinveld, D.J.B.; Hamada, S.R.; Sandroni, C. Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1642–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, E.E.; Moore, H.B.; Kornblith, L.Z.; Neal, M.D.; Hoffman, M.; Mutch, N.J.; Schöchl, H.; Hunt, B.J.; Sauaia, A. Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, D.; Dinardo, J.A. TEG and ROTEM: Technology and Clinical Applications. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 89, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einersen, P.M.; Moore, E.E.; Chapman, M.P.; Moore, H.B.; Gonzalez, E.; Silliman, C.C.; Banerjee, A.; Sauaia, A. Rapid Thrombelastography Thresholds for Goal-Directed Resuscitation of Patients at Risk for Massive Transfusion. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017, 82, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, G.; Agostini, V.; Rondinelli, B.; Russo, E.; Bastianini, B.; Bini, G.; Bulgarelli, S.; Cingolani, E.; Donato, A.; Gambale, G.; et al. Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: Impact of the Early Coagulation Support Protocol on Blood Product Consumption, Mortality and Costs. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossaint, R.; Afshari, A.; Bouillon, B.; Cerny, V.; Cimpoesu, D.; Curry, N.; Duranteau, J.; Filipescu, D.; Grottke, O.; Grønlykke, L.; et al. The European Guideline on Management of Major Bleeding and Coagulopathy Following Trauma: Sixth Edition. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartert, H. Blood Clotting Studies with Thrombus Stressography; a New Investigation Procedure. Klin. Wochenschr. 1948, 26, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volod, O.; Runge, A. Measurement of Blood Viscoelasticity Using Thromboelastography. In Hemostasis and Thrombosis; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 709–724. [Google Scholar]

- Faraoni, D.; DiNardo, J.A. Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays: Update on Technology and Clinical Applications. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhart, J.G.; Smith, R.P.; Hill, T.M.; Winfield, R.D. What, When, and Why: Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays and Their Uses in Trauma Resuscitation. Am. Surg. 2025, 91, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, B.J.A.; See Tow, H.X.; Fong, A.T.W.; Ling, R.R.; Shekar, K.; Teoh, K.; Ti, L.K.; MacLaren, G.; Fan, B.E.; Ramanathan, K. Monitoring Hemostatic Function during Cardiac Surgery with Point-of-Care Viscoelastic Assays: A Narrative Review. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Farber, M.; Getrajdman, C.; Hamburger, J.; Reale, S.; Butwick, A. The Role of Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays for Postpartum Hemorrhage Management and Bedside Intrapartum Care. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, S1089–S1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspari, R.; Aceto, P.; Carelli, S.; Avolio, A.W.; Bocci, M.G.; Postorino, S.; Spinazzola, G.; Caporale, M.; Giuliante, F.; Antonelli, M. Discrepancy Between Conventional Coagulation Tests and Thromboelastography During the Early Postoperative Phase of Liver Resection in Neoplastic Patients: A Prospective Study Using the New-Generation TEG®6s. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarlatescu, E.; Juffermans, N.P.; Thachil, J. The Current Status of Viscoelastic Testing in Septic Coagulopathy. Thromb. Res. 2019, 183, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, C.; Silvestri, I.; Caccioppola, A.; Meli, A.; Grasselli, G.; Panigada, M. Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays in Sepsis: From Pathophysiology to Potential Clinical Implications. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, B.; Voelckel, W.; Zipperle, J.; Grottke, O.; Schöchl, H. Comparison between the New Fully Automated Viscoelastic Coagulation Analysers TEG 6s and ROTEM Sigma in Trauma Patients. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 36, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohi, K.; Singh, J.; Heron, M.; Coats, T. Acute Traumatic Coagulopathy. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2003, 54, 1127–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maegele, M.; Lefering, R.; Yucel, N.; Tjardes, T.; Rixen, D.; Paffrath, T.; Simanski, C.; Neugebauer, E.; Bouillon, B. Early Coagulopathy in Multiple Injury: An Analysis from the German Trauma Registry on 8724 Patients. Injury 2007, 38, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capponi, A.; Rostagno, C. Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: A Review of Specific Molecular Mechanisms. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P.I.; Sørensen, A.M.; Perner, A.; Welling, K.L.; Wanscher, M.; Larsen, C.F.; Ostrowski, S.R. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation or Acute Coagulopathy of Trauma Shock Early after Trauma? An Observational Study. Crit. Care 2011, 15, R272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Raoof, M.; Chen, Y.; Sumi, Y.; Sursal, T.; Junger, W.; Brohi, K.; Itagaki, K.; Hauser, C.J. Circulating Mitochondrial DAMPs Cause Inflammatory Responses to Injury. Nature 2010, 464, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P.I.; Stensballe, J.; Rasmussen, L.S.; Ostrowski, S.R. A High Admission Syndecan-1 Level, A Marker of Endothelial Glycocalyx Degradation, Is Associated with Inflammation, Protein C Depletion, Fibrinolysis, and Increased Mortality in Trauma Patients. Ann. Surg. 2011, 254, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, S.R.; Johansson, P.I. Endothelial Glycocalyx Degradation Induces Endogenous Heparinization in Patients with Severe Injury and Early Traumatic Coagulopathy. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 73, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.J.; Call, M.; Nelson, M.; Calfee, C.S.; Esmon, C.T.; Brohi, K.; Pittet, J.F. Critical Role of Activated Protein C in Early Coagulopathy and Later Organ Failure, Infection and Death in Trauma Patients. Ann. Surg. 2012, 255, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, H.B.; Moore, E.E.; Gonzalez, E.; Chapman, M.P.; Chin, T.L.; Silliman, C.C.; Banerjee, A.; Sauaia, A. Hyperfibrinolysis, Physiologic Fibrinolysis, and Fibrinolysis Shutdown. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014, 77, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajzar, L.; Jain, N.; Wang, P.; Walker, J.B. Thrombin Activatable Fibrinolysis Inhibitor: Not Just an Inhibitor of Fibrinolysis. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, S320–S324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, M.E.; Redick, B.J.; McCreery, R.C.; Crane, I.M.; Greenberg, M.D.; Cachola, L.M.; Nelson, M.F.; Cohen, M.J. Characterization of Platelet Dysfunction after Trauma. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 73, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.; Lefering, R.; Maegele, M.; Gruen, R.L.; Mitra, B. Early Prediction of Acute Traumatic Coagulopathy: A Validation of the COAST Score Using the German Trauma Registry. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2021, 47, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M.L.; Minon, J.M.; Seidel, L.; Poplavsky, J.L.; Vergnion, M. Prehospital Identification of Trauma Patients with Early Acute Coagulopathy and Massive Bleeding: Results of a Prospective Non-Interventional Clinical Trial Evaluating the Trauma Induced Coagulopathy Clinical Score (TICCS). Crit. Care 2014, 18, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Maekawa, K.; Kushimoto, S.; Kato, H.; Sasaki, J.; Ogura, H.; Matauoka, T.; Uejima, T.; Morimura, N.; Ishikura, H.; et al. High D-Dimer Levels Predict a Poor Outcome in Patients with Severe Trauma, Even with High Fibrinogen Levels on Arrival. Shock 2016, 45, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, K.G.; Brummel, K.; Butenas, S. What Is All That Thrombin For? J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003, 1, 1504–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.; Monroe, D.M. A Cell-Based Model of Hemostasis. Thromb. Haemost. 2001, 85, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizoli, S.B.; Scarpelini, S.; Callum, J.; Nascimento, B.; Mann, K.G.; Pinto, R.; Jansen, J.; Tien, H.C. Clotting Factor Deficiency in Early Trauma-Associated Coagulopathy. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2011, 71, S427–S434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaz, B.H.; Winkler, A.M.; James, A.B.; Hillyer, C.D.; MacLeod, J.B. Pathophysiology of Early Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: Emerging Evidence for Hemodilution and Coagulation Factor Depletion. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2011, 70, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baksaas-Aasen, K.; Van Dieren, S.; Balvers, K.; Juffermans, N.P.; Næss, P.A.; Rourke, C.; Eaglestone, S.; Ostrowski, S.R.; Stensballe, J.; Stanworth, S.; et al. Data-Driven Development of ROTEM and TEG Algorithms for the Management of Trauma Hemorrhage. Ann. Surg. 2019, 270, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, E.; Pieracci, F.; Moore, E.; Kashuk, J. Coagulation Abnormalities in the Trauma Patient: The Role of Point-of-Care Thromboelastography. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2010, 36, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meizoso, J.P.; Moore, E.E.; Pieracci, F.M.; Saberi, R.A.; Ghasabyan, A.; Chandler, J.; Namias, N.; Sauaia, A. Role of Fibrinogen in Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2022, 234, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harr, J.N.; Moore, E.E.; Ghasabyan, A.; Chin, T.L.; Sauaia, A.; Banerjee, A.; Silliman, C.C. Functional fibrinogen assays indicates that fibirnogem is critical in correcting abnormal clot strength following trauma. Shock 2013, 39, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juffermans, N.P.; Wirtz, M.R.; Balvers, K.; Baksaas-Aasen, K.; van Dieren, S.; Gaarder, C.; Naess, P.A.; Stanworth, S.; Johansson, P.I.; Stensballe, J.; et al. Towards Patient-specific Management of Trauma Hemorrhage: The Effect of Resuscitation Therapy on Parameters of Thromboelastometry. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 17, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, I.; Davenport, R.; Rourke, C.; Platton, S.; Manson, J.; Spoors, C.; Khan, S.; De’Ath, H.D.; Allard, S.; Hart, D.P.; et al. The Incidence and Magnitude of Fibrinolytic Activation in Trauma Patients. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, B.A.; Harvin, J.A.; Kostousouv, V.; Minei, K.M.; Radwan, Z.A.; Schöchl, H.; Wade, C.E.; Holcomb, J.B.; Matijevic, N. Hyperfibrinolysis at Admission Is an Uncommon but Highly Lethal Event Associated with Shock and Prehospital Fluid Administration. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 73, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.B.; Moore, E.E.; Liras, I.N.; Gonzalez, E.; Harvin, J.A.; Holcomb, J.B.; Sauaia, A.; Cotton, B.A. Acute Fibrinolysis Shutdown after Injury Occurs Frequently and Increases Mortality: A Multicenter Evaluation of 2,540 Severely Injured Patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2016, 222, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloos, P.H.; Vulliamy, P.; van ’t Veer, C.; Sen Gupta, A.; Neal, M.D.; Brohi, K.; Juffermans, N.P.; Kleinveld, D.J.B. Platelet Dysfunction after Trauma: From Mechanisms to Targeted Treatment. Transfusion 2022, 62, S281–S300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verni, C.C.; Davila, A.; Balian, S.; Sims, C.A.; Diamond, S.L. Platelet Dysfunction during Trauma Involves Diverse Signaling Pathways and an Inhibitory Activity in Patient-Derived Plasma. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019, 86, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, C.A.; Oetken, H.J.; Roberti, G.J.; Dewey, E.N.; Goodman, A.; Schreiber, M. Thromboelastography with Platelet Mapping: Limited Predictive Ability in Detecting Preinjury Antiplatelet Agent Use. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021, 91, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardi, G.; Agostini, V.; Rondinelli, B.M.; Bocci, G.; Di Bartolomeo, S.; Bini, G.; Chiara, O.; Cingolani, E.; De Blasio, E.; Gordini, G.; et al. Prevention and Treatment of Trauma Induced Coagulopathy (TIC). An Intended Protocol from the Italian Trauma Update Research Group. J. Anesthesiol. Clin. Sci. 2013, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipperle, J.; Schmitt, F.C.F.; Schöchl, H. Point-of-Care, Goal-Directed Management of Bleeding in Trauma Patients. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2023, 29, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöchl, H.; Voelckel, W.; Schlimp, C.J. Management of Traumatic Haemorrhage—The European Perspective. Anaesthesia 2015, 70, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.; Inaba, K.; Branco, B.C.; Okoye, O.; Schochl, H.; Talving, P.; Lam, L.; Shulman, I.; Nelson, J.; Demetriades, D. Hyperfibrinolysis Elicited via Thromboelastography Predicts Mortality in Trauma. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2012, 215, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M.P.; Moore, E.E.; Moore, H.B.; Gonzalez, E.; Morton, A.P.; Chandler, J.; Fleming, C.D.; Ghasabyan, A.; Silliman, C.C.; Banerjee, A.; et al. The “Death Diamond”. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015, 79, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.-J.; Park, S.-W.; Bae, B.-K.; Lee, S.-H.; Choi, H.J.; Park, S.J.; Ahn, T.Y.; Goh, T.S.; Lee, M.J.; Yeom, S.R. FIBTEM Improves the Sensitivity of Hyperfibrinolysis Detection in Severe Trauma Patients: A Retrospective Study Using Thromboelastometry. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantry, U.S.; Hartmann, J.; Neal, M.D.; Schöechl, H.; Bliden, K.P.; Agarwal, S.; Mason, D.; Dias, J.D.; Mahla, E.; Gurbel, P.A. The Role of Viscoelastic Testing in Assessing Peri-Interventional Platelet Function and Coagulation. Platelets 2022, 33, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schriner, J.B.; George, M.J.; Cardenas, J.C.; Olson, S.D.; Mankiewicz, K.A.; Cox, C.S.; Gill, B.S.; Wade, C.E. Platelet function in trauma: Is current technology in function testing missing the mark in injured patients? Shock 2022, 58, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, E.; Moore, E.E.; Moore, H.B.; Chapman, M.P.; Chin, T.L.; Ghasabyan, A.; Wohlauer, M.V.; Barnett, C.C.; Bensard, D.D.; Biffl, W.L.; et al. Goal-Directed Hemostatic Resuscitation of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy a Pragmatic Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing a Viscoelastic Assay to Conventional Coagulation Assays. Ann. Surg. 2016, 263, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baksaas-Aasen, K.; Gall, L.S.; Stensballe, J.; Juffermans, N.P.; Curry, N.; Maegele, M.; Brooks, A.; Rourke, C.; Gillespie, S.; Murphy, J.; et al. Viscoelastic Haemostatic Assay Augmented Protocols for Major Trauma Haemorrhage (ITACTIC): A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, P.; Pasquier, P.; Rimmele, T.; David, J.S. Trauma Patients Do Not Benefit from a Viscoelastic Haemostatic Assay-Guided Protocol, but Why? Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, C.; Davenport, R.; Baksaas-Aasen, K.; Kolstadbråten, K.M.; Naess, P.A.; Curry, N.; Maegele, M.; Juffermans, N.; Stanworth, S.; Stensballe, J.; et al. Correction of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy by Goal-Directed Therapy: A Secondary Analysis of the ITACTIC Trial. Anesthesiology 2024, 141, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.S.; James, A.; Orion, M.; Selves, A.; Bonnet, M.; Glasman, P.; Vacheron, C.H.; Raux, M. Thromboelastometry-Guided Haemostatic Resuscitation in Severely Injured Patients: A Propensity Score-Matched Study. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunskill, S.J.; Disegna, A.; Wong, H.; Fabes, J.; Desborough, M.J.; Dorée, C.; Davenport, R.; Curry, N.; Stanworth, S.J. Blood Transfusion Strategies for Major Bleeding in Trauma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 2025, CD012635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, S.; Winter, E.; Chanes, N.M.; Hynes, A.M.; Subramanian, M.; Smith, A.A.; Seamon, M.J.; Cannon, J.W. Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays Are Associated with Mortality and Blood Transfusion in a Multicenter Cohort. JACEP Open 2025, 6, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, M.D.; Moore, E.E.; Walsh, M.; Thomas, S.; Callcut, R.A.; Kornblith, L.Z.; Schreiber, M.; Ekeh, A.P.; Singer, A.J.; Lottenberg, L.; et al. A Comparison between the TEG 6s and TEG 5000 Analyzers to Assess Coagulation in Trauma Patients. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020, 88, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.L.; McCully, B.H.; Rick, E.A.; Dewey, E.; Farrell, D.H.; Morrison, L.J.; McMullan, J.; Robinson, B.R.H.; Callum, J.; Tibbs, B.; et al. Tranexamic Acid Administration in the Field Does Not Affect Admission Thromboelastography after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020, 89, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRASH-2 trial collaborators. Effects of Tranexamic Acid on Death, Vascular Occlusive Events, and Blood Transfusion in Trauma Patients with Significant Haemorrhage (CRASH-2): A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The CRASH-3 trial collaborators. Effects of Tranexamic Acid on Death, Disability, Vascular Occlusive Events and Other Morbidities in Patients with Acute Traumatic Brain Injury (CRASH-3): A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, J.B.; Tilley, B.C.; Baraniuk, S.; Fox, E.E.; Wade, C.E.; Podbielski, J.M.; Del Junco, D.J.; Brasel, K.J.; Bulger, E.M.; Callcut, R.A.; et al. Transfusion of Plasma, Platelets, and Red Blood Cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 Ratio and Mortality in Patients with Severe Trauma: The PROPPR Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2015, 313, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innerhofer, P.; Fries, D.; Mittermayr, M.; Innerhofer, N.; von Langen, D.; Hell, T.; Gruber, G.; Schmid, S.; Friesenecker, B.; Lorenz, I.H.; et al. Reversal of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy Using First-Line Coagulation Factor Concentrates or Fresh Frozen Plasma (RETIC): A Single-Centre, Parallel-Group, Open-Label, Randomised Trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017, 4, e258–e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Luz, L.T.; Karkouti, K.; Carroll, J.; Grewal, D.; Jones, M.; Altmann, J.; Lin, Y.; Gupta, A.; Nathens, A.B.; Kron, A.; et al. Factors in the Initial Resuscitation of Patients with Severe Trauma: The FiiRST-2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2532702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

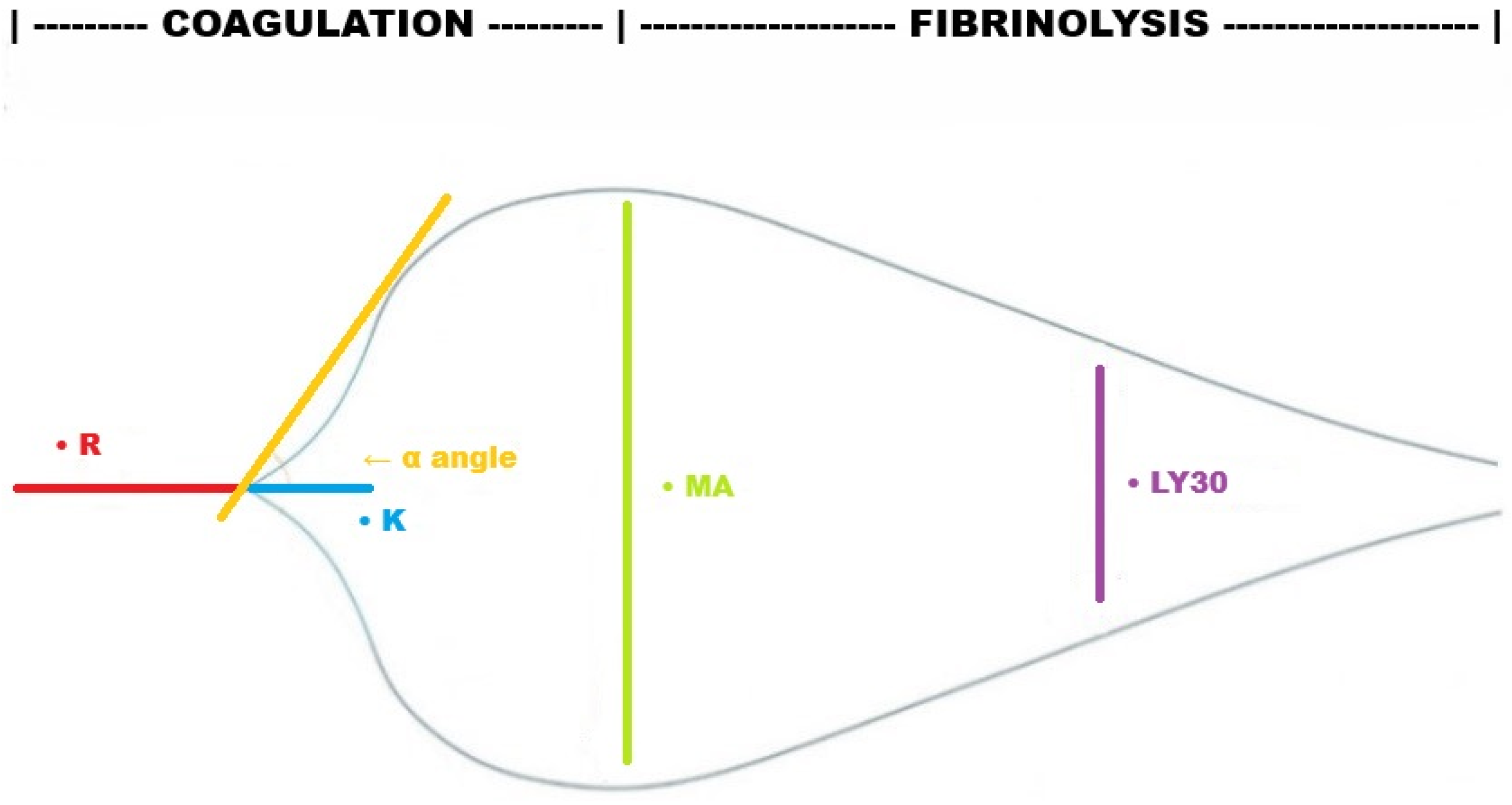

| Phase | TEG | ROTEM | Definition | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clot initiation | R (reaction time) ACT (activated clotting time) | CT (clotting time) | Time to initial clot formation (2 mm amplitude) Time to the beginning of clot formation | Prolonged in coagulation factor deficiency and/or consumption, anticoagulant therapy |

| Clot propagation | K (kinetics) | CFT (clot formation time) | Time from initial clot to defined firmness (2–20 mm amplitude) | Prolonged in low fibrinogen levels or impaired platelet function |

| α-Angle | α-Angle | Angle formed by the tangent line when the clot amplitude reaches 2 mm | Reflects the speed of fibrin build-up; reduced in low fibrinogen levels or, to a lesser extent, in impaired platelet function | |

| Clot stabilization | MA (maximum amplitude) | MCF (maximum clot firmness) | The maximum width of the tracing, representing the maximal clot strength | Decreased in platelet dysfunction or low fibrinogen levels |

| Clot degradation | LY30 (lysis 30 min after MA, as % of MA) | LI30 (lysis index 30 min after MCF, as % of MCF), ML (maximum lysis, as % of MCF) | Degree of clot breakdown over time | Increased in hyperfibrinolysis Reduced in fibrinolysis shutdown |

| Assay | Activator | Pathway | Main Measurements | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaolin TEG (CK) | Kaolin | Intrinsic | R, K, α-angle, MA, LY30 | Standard TEG test. Assesses clotting factors function, platelet–fibrin interaction, and lysis |

| Rapid TEG (CRT) | Kaolin + Tissue Factor | Accelerated intrinsic + extrinsic | ACT, R, K, α-angle, MA, LY30 | Faster clot initiation for rapid decision-making |

| Heparinase TEG (CKH) | Kaolin + Heparinase | Intrinsic heparin-neutralized | R, K, α-angle, MA, LY30 | Compared to the kaolin test, it differentiates the heparin effect from actual coagulopathy |

| Functional Fibrinogen (CFF) | Tissue factor + GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor (e.g., abciximab) | Fibrinogen contribution | MA (fibrinogen-only) | Platelets inhibited; assesses the contribution of fibrinogen to clot strength |

| Assay | Activator | Pathway | Main Measurements | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXTEM | Tissue Factor | Extrinsic | CT, CFT, α-angle, MCF, ML | Standard ROTEM test. Assesses clotting factors function, platelet–fibrin interaction, and lysis |

| INTEM | Ellagic Acid | Intrinsic | CT, CFT, α-angle, MCF, ML | Focus on intrinsic pathway defects |

| HEPTEM | Ellagic Acid + Heparinase | Intrinsic (heparin-neutralized) | CT, CFT, α-angle, MCF, ML | Compared to EXTEM, it differentiates the heparin effect from actual coagulopathy |

| FIBTEM | Tissue Factor + Cytochalasin D | Fibrinogen contribution | MCF | Platelets inhibited; assesses the contribution of fibrinogen to clot strength |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Natalini, D.; Xhemalaj, R.; Carelli, S. Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays in the Management of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: A Clinical Update. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010012

Natalini D, Xhemalaj R, Carelli S. Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays in the Management of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: A Clinical Update. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleNatalini, Daniele, Rikardo Xhemalaj, and Simone Carelli. 2026. "Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays in the Management of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: A Clinical Update" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010012

APA StyleNatalini, D., Xhemalaj, R., & Carelli, S. (2026). Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays in the Management of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: A Clinical Update. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010012