Validation of a Questionnaire Assessing the Link Between Affective State and Physical Activity in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population and Settings

2.3. Study Size

2.4. Data Sources/Measurement

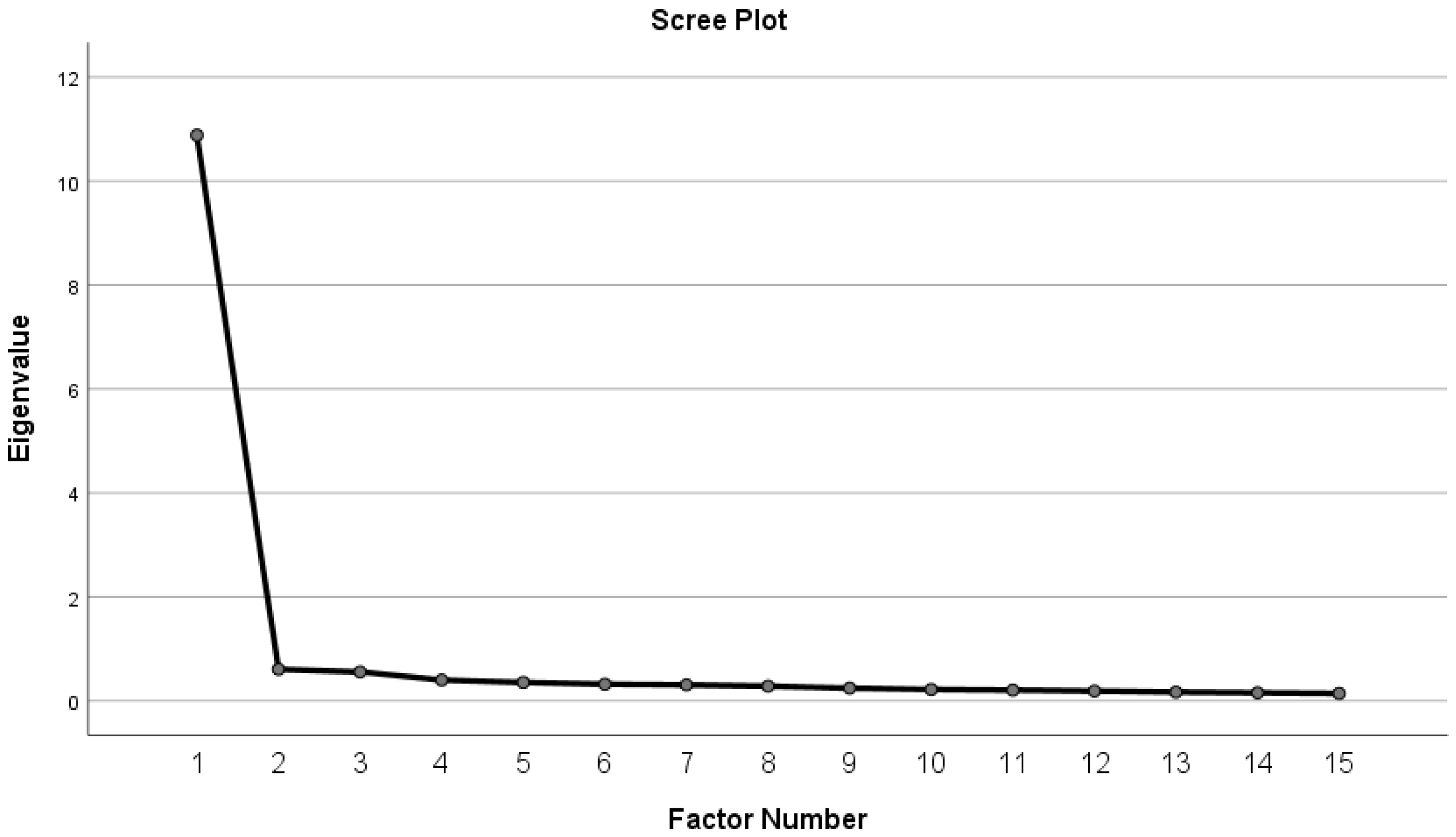

2.5. Variables and Statistical Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wanjau, M.N.; Möller, H.; Haigh, F.; Milat, A.; Hayek, R.; Lucas, P.; Veerman, J.L. Physical Activity and Depression and Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Assessment of Causality. AJPM Focus 2023, 2, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahindru, A.; Patil, P.; Agrawal, V. Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e33475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stults-Kolehmainen, M.A.; Sinha, R. The effects of stress on physical activity and exercise. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 81–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Mateo, D.; Lavín-Pérez, A.M.; Peñacoba, C.; Del Coso, J.; Leyton-Román, M.; Luque-Casado, A.; Gasque, P.; Fernández-Del-Olmo, M.Á.; Amado-Alonso, D. Key Factors Associated with Adherence to Physical Exercise in Patients with Chronic Diseases and Older Adults: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teques, A.P.; de Oliveira, R.F.; Bednarikova, M.; Bertollo, M.; Botwina, G.; Khomutova, A.; Turam, H.E.; Dinç, İ.; López-Flores, M.; Teques, P. Social and Emotional Skills in at-Risk Adolescents through Participation in Sports. Sports 2024, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Romo, G.; Acebes-Sánchez, J.; García-Merino, S.; Garrido-Muñoz, M.; Blanco-García, C.; Diez-Vega, I. Physical Activity and Mental Health in Undergraduate Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCartan, C.J.; Yap, J.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Tully, M.A.; Best, P.; Webb, P.; White, C.; Gilbody, S.; Churchill, R.; et al. Factors that influence participation in physical activity for anxiety or depression: A synthesis of qualitative evidence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD013547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, N.; Bailey, R.P.; Ries, F.; Hashim, S.N.A.B.; Fernandez, J.A. Assessing the impact of physical activity on reducing depressive symptoms: A rapid review. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Mei, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Xi, Y. Association of habitual physical activity with depression and anxiety: A multicentre cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e076095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Peng, S.; Khairani, A.Z.; Liang, J. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Physical Activity Interventions among University Students. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battalio, S.L.; Huffman, S.E.; Jensen, M.P. Longitudinal associations between physical activity, anxiety, and depression in adults with long-term physical disabilities. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boparai, J.K.; Dunnett, S.; Wu, M.; Tassone, V.K.; Duffy, S.F.; Zuluaga Cuartas, V.; Chen, Z.; Jung, H.; Sabiston, C.M.; Lou, W.; et al. The Association Between Depressive Symptoms and the Weekly Duration of Physical Activity Subset by Intensity and Domain: Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey From 2007 to 2018. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2024, 13, e48396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’Connor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iconaru, E.I.; Ciucurel, C. Developing social and civic competencies in people with intellectual disabilities from a family center through an adapted training module. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 3303–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Sepp, H.; Brage, S.; Becker, W.; Jakes, R.; Hennings, M.; Wareham, N.J. Criterion-related validity of the last 7-day, short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in Swedish adults. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, D.J.; Lee, C.C.Y.; Ho, E.Y.K.; Chan, K.L.; Chan, D. Convergent validity of six methods to assess physical activity in daily life. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 101, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). 2005. Available online: https://sites.google.com/view/ipaq/score (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Kroenke, K. PHQ-9: Global uptake of a depression scale. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: A new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002, 32, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Grafe, K.; Kroenke, K.; Quenter, A.; Zipfel, S.; Zipfel, S.; Buchholz, C.; Witte, S.; Herzog, W. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 78, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G. PsyToolkit—A software package for programming psychological experiments using Linux. Behav. Res. Methods 2010, 42, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G. PsyToolkit: A novel web-based method for running online questionnaires and reaction-time experiments. Teach. Psychol. 2017, 44, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursey, K.; Burrows, T.L.; Stanwell, P.; Collins, C.E. How accurate is web-based self-reported height, weight, and body mass index in young adults? J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Coutts, J.J. Use Omega Rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for Estimating Reliability. But…. Commun. Methods Meas. 2020, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; Released 2019; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019.

- Li, Z.; Xue, M.; Sun, Q.; Liu, C.; Guo, Q.; Wang, F.; Deng, L.; Zhang, H. Pedestrian attribute recognition based on multi-task deep learning and label correlation analysis. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Ser. C 2022, 84, 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, C.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Yoon, S.; Ko, Y.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.H.; Jeon, S.W.; Han, C. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression in General Population of Korea: Results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levis, B.; Benedetti, A.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Sun, Y.; Negeri, Z.; He, C.; Wu, Y.; Krishnan, A.; Bhandari, P.M.; Neupane, D.; et al. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores do not accurately estimate depression prevalence: Individual participant data meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 122, 115–128.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, B.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D. DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: Individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 2019, 365, l1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lox, C.L.; Jackson, S.; Tuholski, S.W.; Wasley, D.; Treasure, D.C. Revisiting the Measurement of Exercise-Induced Feeling States: The Physical Activity Affect Scale (PAAS). MPEES 2000, 4, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvin, L.; Rejeski, W.J. The Exercise-Induced Feeling Inventory: Development and initial validation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1993, 15, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, J.; Persson Asplund, R.; Ekblom, Ö.; Blom, V. Psychological responses to acute exercise in patients with stress-induced exhaustion disorder: A cross-over randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, C.R.; Rothman, A.J.; Mann, T. How affective and instrumental physical activity outcomes are associated with motivation, intentions, and engagement in subsequent behavior. Psychol. Sport. Exerc. 2025, 76, 102751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Petruzzello, S.J. Analysis of the affect measurement conundrum in exercise psychology. III. A conceptual and methodological critique of the Subjective Exercise Experiences Scale. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2001, 2, 205–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeski, W.J.; Reboussin, B.A.; Dunn, A.L.; King, A.C.; Sallis, J.F. A Modified Exercise-induced Feeling Inventory for Chronic Training and Baseline Profiles of Participants in the Activity Counseling Trial. J. Health Psychol. 1999, 4, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myring, G.; Mitchell, P.M.; Kernohan, W.G.; McIlfatrick, S.; Cudmore, S.; Finucane, A.M.; Graham-Wisener, L.; Hewison, A.; Jones, L.; Jordan, J.; et al. An analysis of the construct validity and responsiveness of the ICECAP-SCM capability wellbeing measure in a palliative care hospice setting. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iconaru, E.I.; Ciucurel, M.M.; Georgescu, L.; Tudor, M.; Ciucurel, C. The Applicability of the Poincaré Plot in the Analysis of Variability of Reaction Time during Serial Testing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitescu, T.A.; Concea-Prisacaru, A.I.; Sgarciu, V. A Web Service Implementation—Soap vs Rest. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Ser. C 2024, 86, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Age (Years) | W (kg) | H (cm) | IPAQ-SF MET | PHQ-9 Score | ASPAQ Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 37.81 | 67.15 | 167.66 | 1451.95 | 6.90 | 25.89 |

| SD | 13.05 | 12.16 | 7.63 | 1686.12 | 3.72 | 14.80 |

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 145 | 35.2 |

| Female | 267 | 64.8 | |

| IPAQ-SF Category | Low PA | 231 | 56.1 |

| Moderate PA | 112 | 27.2 | |

| High PA | 69 | 16.7 | |

| PHQ-9 Category | Absent/Minimal depression (0–4) | 112 | 27.2 |

| Mild depression (5–9) | 268 | 65 | |

| Moderate depression (10–14) | 22 | 5.3 | |

| Moderately severe depression (15–19) | 7 | 1.7 | |

| Severe depression (20–27) | 3 | 0.7 | |

| ASPAQ Category | Minimal impact (0–15) | 99 | 24 |

| Mild impact (16–30) | 103 | 25 | |

| Moderate impact (31–45) | 104 | 25.2 | |

| Severe impact (45–60) | 106 | 25.7 |

| Variable | MET | IPAQ-SF Category | PHQ-9 Score | PHQ-9 Category | ASPAQ Score | ASPAQ Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MET | 1.00 | |||||

| IPAQ-SF category | 0.736 * | 1.00 | ||||

| PHQ-9 score | −0.385 * | −0.565 * | 1.00 | |||

| PHQ-9 category | −0.327 * | −0.517 * | 0.766 * | 1.00 | ||

| ASPAQ score | −0.397 * | −0.595 * | 0.617 * | 0.579 * | 1.00 | |

| ASPAQ category | −0.444 * | −0.658 | 0.650 * | 0.628 * | 0.878 * | 1.00 |

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 | Item 10 | Item 11 | Item 12 | Item 13 | Item 14 | Item 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.822 | 0.900 | 0.855 | 0.844 | 0.851 | 0.829 | 0.864 | 0.877 | 0.852 | 0.882 | 0.843 | 0.862 | 0.676 | 0.801 | 0.827 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciucurel, C.; Ciucurel, M.M.; Georgescu, L.; Tudor, M.I.; Olaru, G.A.; Iconaru, E.I. Validation of a Questionnaire Assessing the Link Between Affective State and Physical Activity in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093210

Ciucurel C, Ciucurel MM, Georgescu L, Tudor MI, Olaru GA, Iconaru EI. Validation of a Questionnaire Assessing the Link Between Affective State and Physical Activity in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(9):3210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093210

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiucurel, Constantin, Manuela Mihaela Ciucurel, Luminita Georgescu, Mariana Ionela Tudor, Gabriel Alexandru Olaru, and Elena Ioana Iconaru. 2025. "Validation of a Questionnaire Assessing the Link Between Affective State and Physical Activity in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 9: 3210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093210

APA StyleCiucurel, C., Ciucurel, M. M., Georgescu, L., Tudor, M. I., Olaru, G. A., & Iconaru, E. I. (2025). Validation of a Questionnaire Assessing the Link Between Affective State and Physical Activity in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(9), 3210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093210