Temporo-Mandibular Joint Functional Arthroplasty: Does It Improve the Short-Term Quality of Life in Patients with Painful Anterior Disc Displacement Without Reduction? A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- No previous diagnosis of other TMJ pathologies (trauma, rheumatologic and systemic diseases etc.);

- -

- A diagnosis of unilateral ADDWoR, (according to the diagnostic criteria (DC/TMD) and Wilkes classification);

- -

- A maximum assisted opening movement (MMO) < 40 mm;

- -

- A record of the TMJ VAS score for pain assessment and the QOL TMJ questionnaire results before and at least six months after surgical treatment;

- -

- Non-responsiveness to other non-invasive or minimally invasive techniques.

Statistical Analysis

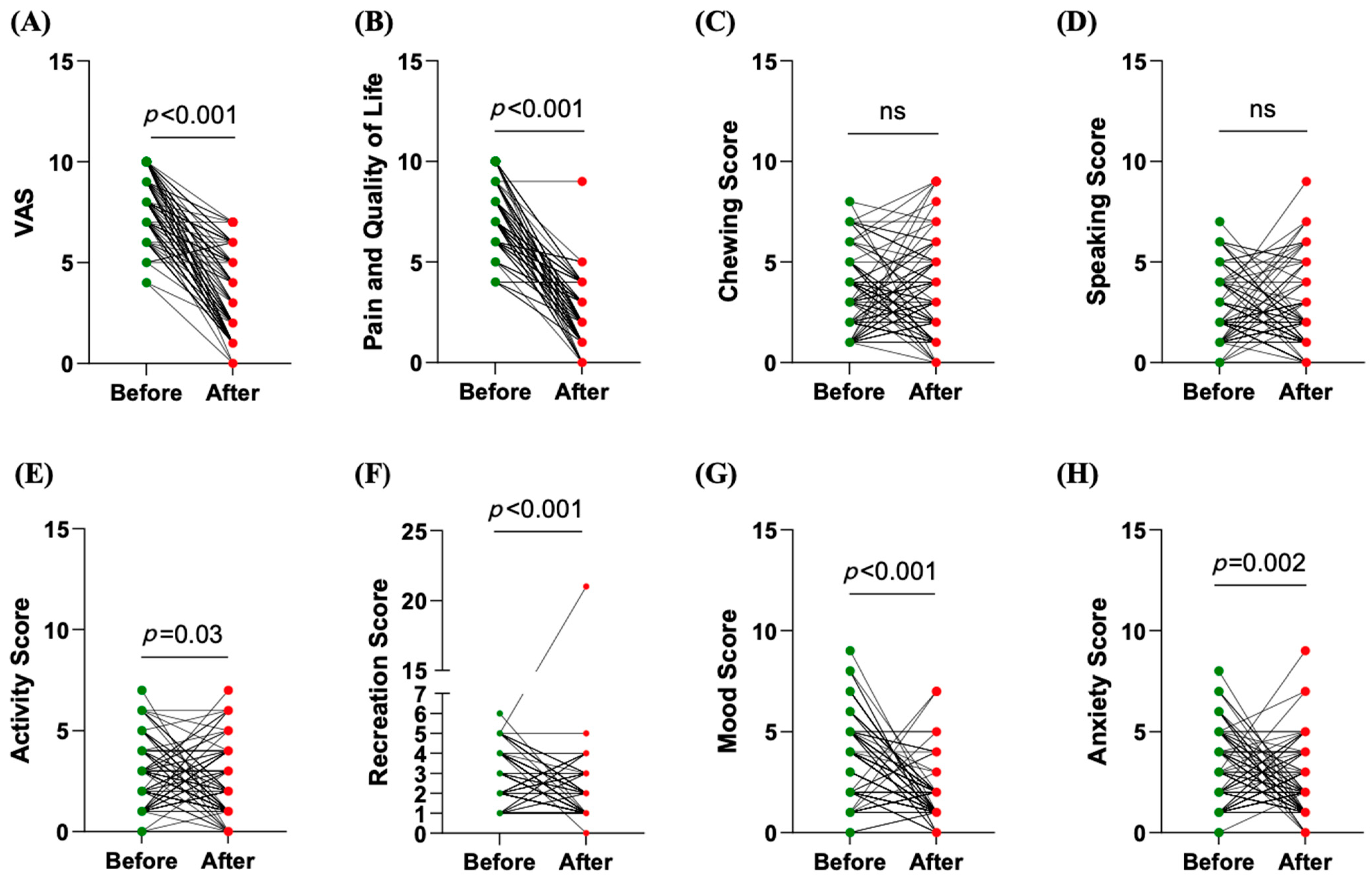

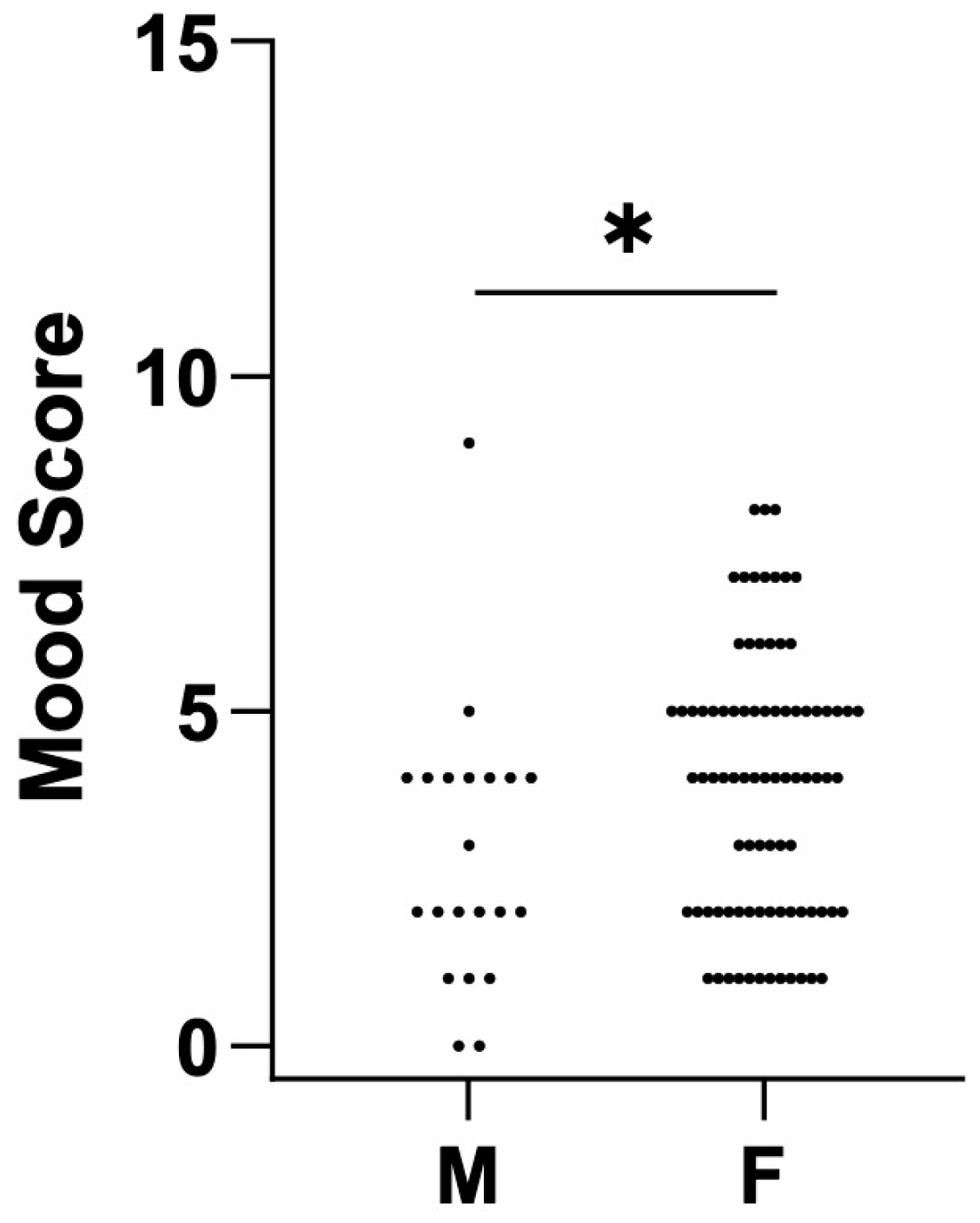

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADDwoR | anterior disc displacement without reduction |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| MMO | maximum assisted opening movement |

| QoL | quality of life |

References

- Dimitroulis, G.; McCullough, M.; Morrison, W. Quality-of-Life Survey Comparing Patients before and after Discectomy of the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, I.; Greenberg, M.S. Clinical Assessment of Patients with Orofacial Pain and Temporomandibular Disorders. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 57, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercuri, L.G. Temporomandibular Joint Disorder Management in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felin, G.C.; Tagliari, C.V.d.C.; Agostini, B.A.; Collares, K. Prevalence of Psychological Disorders in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 132, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miloro, M.; Ghali, E.G.; Larsen, E.P.; Waite, P. Peterson’s Principles of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 4th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk-Zielińska, B.; Ginszt, M. A Meta-Analysis of the Global Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Winocur, E.; Piccotti, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Lobbezoo, F. Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review of Axis I Epidemiologic Findings. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2011, 112, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankestijn, J.; Boering, G. Posterior Dislocation of the Temporomandibular Disc. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1985, 14, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westesson, P.L.; Larheim, T.A.; Tanaka, H. Posterior Disc Displacement in the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1998, 56, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.L.; Westesson, P.L. Temporomandibular Joint: Value of Coronal MR Images. Radiology 1993, 188, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzberg, R.W.; Westesson, P.L.; Tallents, R.H.; Anderson, R.; Kurita, K.; Manzione, J.V.; Totterman, S. Temporomandibular Joint: MR Assessment of Rotational and Sideways Disk Displacements. Radiology 1988, 169, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre Canales, G.; Manfredini, D.; Grillo, C.M.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Machado Gonçalves, L.; Rizzatti Barbosa, C.M. Therapeutic Effectiveness of a Combined Counseling plus Stabilization Appliance Treatment for Myofascial Pain of the Jaw Muscles: A Pilot Study. Cranio 2017, 35, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wänman, A.; Marklund, S. Treatment Outcome of Supervised Exercise, Home Exercise and Bite Splint Therapy, Respectively, in Patients with Symptomatic Disc Displacement with Reduction: A Randomised Clinical Trial. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montinaro, F.; Nucci, L.; d’Apuzzo, F.; Perillo, L.; Chiarenza, M.C.; Grassia, V. Oral Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs as Treatment of Joint and Muscle Pain in Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review. Cranio 2024, 42, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Prasad, R.; Punga, R.; Datta, R.; Singh, N. A Comparison of the Outcomes Following Intra-Articular Steroid Injection Alone or Arthrocentesis Alone in the Management of Internal Derangement of the Temporomandibular Joint. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 13, S80–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidebottom, A.J. Current Thinking in Temporomandibular Joint Management. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 47, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, S.J. Discectomy for the Treatment of Internal Derangements of the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001, 59, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloro, M.; Henriksen, B. Discectomy as the Primary Surgical Option for Internal Derangement of the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Vijayaragavan, R.; Sharma, P.; Chaudhary, Z.; Verma, A.; Rathaur, A. Is Modified Condylotomy a Better Surgical Option Compared With High-Condylar Shave With Eminectomy in Improving Symptoms of Internal Derangement of Temporomandibular Joint? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 1158–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K.; Hong, J.H. Temporomandibular Joint Disc Plication with MITEK Mini Anchors: Surgical Outcome of 65 Consecutive Joint Cases Using a Minimally Invasive Approach. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 42, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrehem, A.; Hu, Y.K.; Yang, C.; Zheng, J.S.; Shen, P.; Shen, Q.C. Arthroscopic versus Open Disc Repositioning and Suturing Techniques for the Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint Anterior Disc Displacement: 3-Year Follow-up Study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, J.R.; Cassano, D.S.; Rezende, L.; Wolford, L.M. Disc Repositioning: Does It Really Work? Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 27, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakailly, X.; Schwartz, D.; Alwanni, N.; Demko, C.; Altay, M.A.; Kilinc, Y.; Baur, D.A.; Quereshy, F. Patient-Centered Quality of Life Measures after Alloplastic Temporomandibular Joint Replacement Surgery. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascone, P.; Spallaccia, F.; Vellone, V. Temporomandibular Joint Surgery: Open Discopexy and “Functional Arthroplasty”. Atlas Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 30, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Yang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wilson, J.J. Modified Temporomandibular Joint Disc Repositioning with Miniscrew Anchor: Part I--Surgical Technique. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, e1–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.-P.; List, T.; Svensson, P.; Gonzalez, Y.; Lobbezoo, F.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group†. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014, 28, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, C.H. Internal Derangements of the Temporomandibular Joint: Pathological Variations. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1989, 115, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ângelo, D.F. A Letter to the Editor on “Root of Helix Inter Tragus Notch Incision (RHITNI) for Temporomandibular Open Surgery”. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 83, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, W.S. Illustrated Surgical Techniques for Management of Impingements of the Temporomandibular Joint. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 42, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, P.; Wolford, L.M. The Mitek Mini Anchor for TMJ Disc Repositioning: Surgical Technique and Results. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001, 30, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spallaccia, F.; Rivaroli, A.; Basile, E.; Cascone, P. Disk Repositioning Surgery of the Temporomandibular Joint with Bioabsorbable Anchor. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2013, 24, 1792–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weymuller, E.A.; Alsarraf, R.; Yueh, B.; Deleyiannis, F.W.B.; Coltrera, M.D. Analysis of the Performance Characteristics of the University of Washington Quality of Life Instrument and Its Modification (UW-QOL-R). Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2001, 127, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.J.; Ellis, O.G.; Tocaciu, S.; McCullough, M.J.; Dimitroulis, G. A 2-Year Comparison of Quality of Life Outcomes between Biomet Stock and OMX Custom Temporomandibular Joint Replacements. Adv. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 5, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitroulis, G. Comparison of the Outcomes of Three Surgical Treatments for End-Stage Temporomandibular Joint Disease. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerre-Bastos, J.J.; Miller, C.P.; Li, Y.; Andersen, J.R.; Karsdal, M.; Bihlet, A.R. Associations between Single-Question Visual Analogue Scale Pain Score and Weight-Bearing and Non-Weight-Bearing Domains of Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index Pain: Data from 2 Phase 3 Clinical Trials. Pain Rep. 2022, 7, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fang, X.; Qi, B.; Xiao, W.; Pan, Z.; Xie, Z. Comparing the Efficacy of Anatomical Locked Plate Fixation with Coracoclavicular Ligament Augmentation to Hook Plate Fixation in Treating Distal Clavicle Fractures. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 3358–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehme, C.; Fritsch, B.; Thomas, L.; Istin, S.; Burchert, C.; Hummel, B.; Baleanu-Curaj, B.; Reis, H.; Szarvas, T.; Ruebben, H.; et al. Clinical Outcome and Quality of Life in Octogenarian Patients with Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder Treated with Radical Cystectomy or Transurethral Resection of the Bladder Tumor: A Retrospective Analysis of 143 Patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2022, 54, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubaiti, A. Sample Size Determination: A Practical Guide for Health Researchers. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2022, 24, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascone, P.; Ramieri, V.; Arangio, P.; Vellone, V.; Tarsitano, A.; Marchetti, C. TMJ Inferior Compartment Arthroplasty Procedure through a 25-Year Follow-up (Functional Arthroplasty). Ann. Stomatol. 2016, 7, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spallaccia, F.; Vellone, V.; Colangeli, W.; De Tomaso, S. Maxillofacial Fractures in the Province of Terni (Umbria, Italy) in the Last 11 Years: Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2022, 33, E853–E858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Rating | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A. PAIN | 1 | I have no pain. |

| 2 | There is mild pain, but I do not need medication. | |

| 3 | I have moderate pain, which requires regular analgesics (e.g., paracetamol). | |

| 4 | I have severe pain controlled only by strong analgesics (e.g., Panadeine Forte). | |

| 5 | I have severe pain, which is not controlled by analgesics. | |

| B. DIET AND CHEWING | 1 | I can chew and eat whatever I like. |

| 2 | I can chew most things, except tough foods like steak and apples. | |

| 3 | I only stick to soft foods, such as pasta and soft bread. | |

| 4 | I need to cut all food into small pieces. | |

| 5 | I can only eat food that has been put through a blender. | |

| C. SPEECH | 1 | My speech is normal. |

| 2 | I have difficulty saying some words. | |

| 3 | I have difficulty in being understood over the telephone. | |

| 4 | Only my friends and family can understand me. | |

| 5 | I cannot be understood at all. | |

| D. ACTIVITY | 1 | I am as active as I have ever been. |

| 2 | There are times when I can’t keep up my old pace, but not often. | |

| 3 | I am often tired and have slowed down my activities, though I still get out. | |

| 4 | I don’t go out very often because I don’t have the strength. | |

| 5 | I am usually in bed or a chair and don’t leave home. | |

| E. RECREATION | 1 | There are no limitations to recreation at home or away from home. |

| 2 | There are a few things I can’t do, but I still get out and enjoy life. | |

| 3 | There are many times when I wish I could get out more, but I am not up to it. | |

| 4 | There are severe limitations to what I can do; mostly, I stay at home and watch TV. | |

| 5 | I can’t do anything enjoyable. | |

| F. MOOD | 1 | My mood is excellent and unaffected by my TMJ disorder. |

| 2 | My mood is generally good and only occasionally affected by my TMJ disorder. | |

| 3 | I am neither in a good mood nor depressed about my TMJ disorder. | |

| 4 | I am somewhat depressed about my TMJ disorder. | |

| 5 | I am extremely depressed about my TMJ disorder. | |

| G. ANXIETY | 1 | I am not anxious about my TMJ disorder. |

| 2 | I am a little anxious about my TMJ disorder, but I am coping. | |

| 3 | I am very anxious about my TMJ disorder and finding it difficult to cope. | |

| 4 | I am severely anxious about my TMJ disorder and not coping at all. | |

| H. Issues Most on Your Mind (Circle up to 3 answers) | 1 | Nothing |

| 2 | Pain | |

| 3 | Diet and chewing | |

| 4 | Speech | |

| 5 | Activity levels | |

| 6 | Recreation | |

| 7 | Mood | |

| 8 | Anxiety | |

| I. Compared to the Month Before Surgery, How Would You Rate Your Overall Health-Related Quality of Life? (Post-Surgical Patients Only) | 1 | Much better |

| 2 | Somewhat better | |

| 3 | About the same | |

| 4 | Somewhat worse | |

| 5 | Much worse | |

| J. How Would You Rate Your Health-Related Quality of Life Over the Past Month? | 1 | Excellent |

| 2 | Very good | |

| 3 | Good | |

| 4 | Fair | |

| 5 | Poor | |

| K. How Would You Rate Your Overall Quality of Life Over the Past Month (Considering Factors Such as Family, Friends, Spirituality, and Leisure Activities)? | 1 | Excellent |

| 2 | Very good | |

| 3 | Good | |

| 4 | Fair | |

| 5 | Poor | |

| L. If a Relative or Friend Had TMJ Problems Similar to Yours, Would You | 1 | Recommend TMJ surgery as the primary treatment |

| 2 | Recommend TMJ surgery only if other measures (e.g., physiotherapy, splint therapy, medications) fail | |

| 3 | Recommend TMJ surgery only as a very last resort | |

| 4 | Not recommend TMJ surgery at all |

| Spearman’s Rho Correlation | VAS | Pain and Quality-of-Life Score | Activity Score | Recreation Score | Mood Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain and Quality of Life score | ρ = 0.19 η2 = 0.04 p = 0.046 | / | / | / | |

| Activity score | ρ = − 0.21 η2 = 0.04 p = 0.028 | ρ = −0.23 η2 = 0.05 p = 0.018 | / | / | |

| Recreation score | ρ = −0.004 p = 0.965 | ρ = −0.09 p = 0.342 | ρ = −0.05 p = 0.581 | / | |

| Mood score | ρ = 0.36 η2 = 0.13 p < 0.001 | ρ = −0.16 p = 0.090 | ρ = −0.002 p = 0.984 | ρ = −0.22 η2 = 0.05 p = 0.024 | |

| Anxiety score | ρ = −0.1 p = 0.324 | ρ = −0.20 p = 0.053 | ρ = 0.09 p = 0.376 | ρ = 0.05 p = 0.628 | ρ = −0.12 p = 0.205 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spallaccia, F.; De Tomaso, S.; Cirignaco, G.; Angelo, D.F.; Vaira, L.A.; Vellone, V. Temporo-Mandibular Joint Functional Arthroplasty: Does It Improve the Short-Term Quality of Life in Patients with Painful Anterior Disc Displacement Without Reduction? A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082560

Spallaccia F, De Tomaso S, Cirignaco G, Angelo DF, Vaira LA, Vellone V. Temporo-Mandibular Joint Functional Arthroplasty: Does It Improve the Short-Term Quality of Life in Patients with Painful Anterior Disc Displacement Without Reduction? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(8):2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082560

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpallaccia, Fabrizio, Silvia De Tomaso, Giulio Cirignaco, David Faustino Angelo, Luigi Angelo Vaira, and Valentino Vellone. 2025. "Temporo-Mandibular Joint Functional Arthroplasty: Does It Improve the Short-Term Quality of Life in Patients with Painful Anterior Disc Displacement Without Reduction? A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 8: 2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082560

APA StyleSpallaccia, F., De Tomaso, S., Cirignaco, G., Angelo, D. F., Vaira, L. A., & Vellone, V. (2025). Temporo-Mandibular Joint Functional Arthroplasty: Does It Improve the Short-Term Quality of Life in Patients with Painful Anterior Disc Displacement Without Reduction? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(8), 2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082560