Burnout, Associated Factors, and Mental Health Measures Among Ecuadorian Physicians: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

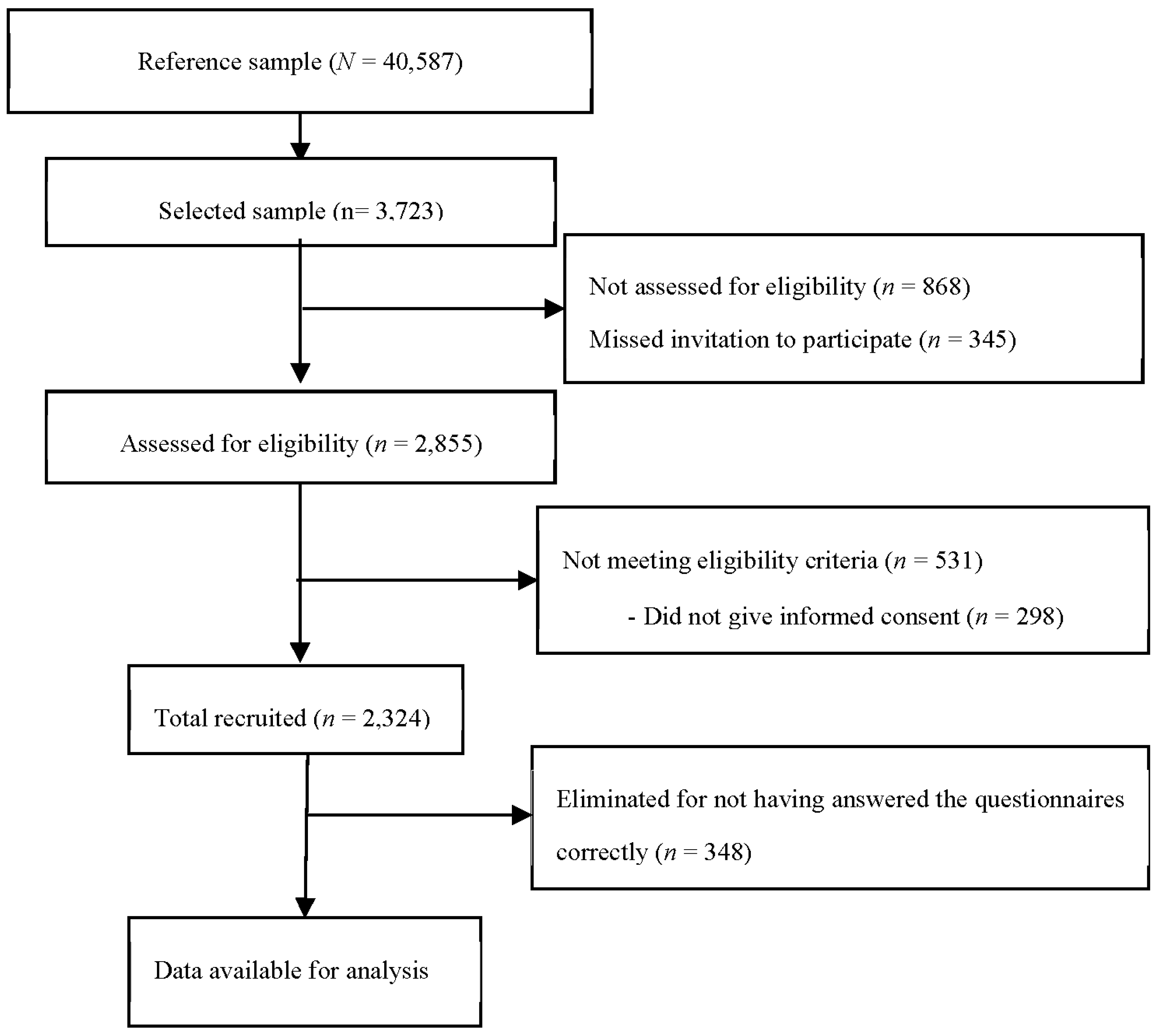

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Sociodemographic and Organizational Questionnaire

2.2.2. Burnout

2.2.3. Psychological Inflexibility

2.2.4. Perceived Loneliness

2.2.5. Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome

3.3. Factors Associated with Burnout

3.4. Mental Health Symptoms in Physicians with and Without Burnout

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 2nd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Dierendonck, D.V. The construct validity of two measures. J. Organiz. Behav. 1993, 14, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, D.S.; Profit, J.; Morgenthaler, T.I.; Satele, D.V.; Sinsky, C.A.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Tutty, M.A.; West, C.P.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout; well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Baker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organiz. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, T.; Lee, D.R. Burnout and physician gender: What do we know? Med. Care 2021, 59, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, E.; García de Alba, J.E. Prevalence of burnout syndrome and associated variables in Mexican medical specialists. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2022, 51, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chênevert, D.; Kilroy, S.; Johnson, K.; Fournier, P.L. The determinants of burnout and professional turnover intentions among Canadian physicians: Application of the job demands-resources model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijakoski, D.; Atanasovska, A.; Bislimovska, D.; Brborović, H.; Brborović, O.; Kezunović, L.C.; Milošević, M.; Minov, J.; Önal, B.; Pranjić, N.; et al. Associations of burnout with job demands/resources during the pandemic in health workers from Southeast European countries. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1258226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagopoulou, E.; Montgomery, A.; Benos, A. Burnout in internal medicine physicians: Differences between residents and specialists. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2006, 17, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, Z.; Dai, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Chen, B. Physician burnout and its associated factors: A cross sectional study in Shanghai. J. Occup. Health 2014, 56, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saijo, Y.; Chiba, S.; Yoshioka, E.; Kawanishi, Y.; Nakagi, Y.; Ito, T.; Sugioka, Y.; Kitaoka-Higashiguchi, K.; Yoshida, T. Job stress and burnout among urban and rural hospital physicians in Japan. Aust. J. Rural Health 2013, 21, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzkopf, D.; Rüddel, H.; Thomas-Rüddel, D.O.; Felfe, J.; Poidinger, B.; Matthäus-Krämer, C.; Hartog, C.S.; Bloos, F. Perceived nonbeneficial treatment of patients, burnout, and intention to leave the job among ICU nurses and junior and senior physicians. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, e265–e273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Balch, C.M.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; Freischlag, J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: A comparison by sex. Arch. Surg. 2011, 146, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Jokic-Begic, N.; Korajlija, A.L.; Begic, D. Mental health of psychiatrists and physicians of other specialties in early Covid-19 pandemic: Risk and protective factors. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.; Polonijo, A.N.; Carpiano, R.M. Getting by with a little help from friends and colleagues: Testing how residents’ social support networks affect loneliness and burnout. Can. Fam. Physician 2016, 62, e677–e683. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.L. Role conflict: Cause of burnout or energizer? Soc. Work 1993, 38, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvanova, R.K.; Muros, J.P. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, N.; Kim, E.K.; Kim, H.; Yang, E.; Lee, S.M. Individual and work-related factors influencing burnout of mental health professionals: A meta-analysis. J. Employ. Couns. 2010, 47, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger-Brown, J.; Rogers, V.E.; Trinkoff, A.M.; Kane, R.L.; Bausell, R.B.; Scharf, S.M. Sleep, sleepiness, fatigue, and performance of 12-hour-shift nurses. Chronobiol. Int. 2012, 29, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.D.; Herst, D.E.; Bruck, C.S.M.; Sutton, M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.Y.; Frey, E.; Chien, W.T.; Cheng, H.Y.; Gloster, A.T. The role of psychological flexibility in the relationships between burnout, job satisfaction, and mental health among nurses in combatting COVID-19: A two-region survey. J. Nurs. Scholarship. 2023, 55, 1068–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Elovainio, M.; Vahtera, J.; Ferrie, J.E. From insecure to secure employment: Changes in work, health, health related behaviours, and sickness absence. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanikola, M.; Papathanassoglou, E.D.; Giannakopoulou, M.; Koutroubas, A. Pilot exploration of the association between self-esteem and professional satisfaction in Helenic hospital nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2007, 15, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, D.; Johnson, S.; Kuipers, E.; Dunn, G.; Szmukler, G.; Reid, Y.; Bebbington, P.; Thornicroft, G. Mental health, “burnout” and job satisfaction in a longitudinal study of mental health staff. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1999, 34, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstad, R.; Sexton, H.; Søgaard, A.J. The Finnmark study: A prospective population study of the social support buffer hypothesis, specific stressors and mental distress. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2001, 36, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston-Hawkins, L.A.; Solorio, F.A.; Chao, G.F.; Green, C.R. The Silent Epidemic: Causes and consequences of medical learner burnout. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, K. Occupational Burnout and Health, People and Work Research, Report 81; Finnish Institute of Occupational Health: Helsinki, Finland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, A. Burnout, job satisfaction, and anxiety-depression among family physicians: A cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 952–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayes, A.; Tavella, G.; Parker, G. The biology of burnout: Causes and consequences. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 22, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaron, M.M.; Segun-Omosehin, O.A.; Matar, R.H.; Beran, A.; Nakanishi, H.; Than, C.A.; Abulseoud, O.A. A systematic review and meta analysis on burnout in physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: A hidden healthcare crisis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1071397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarez-Garcia, A. Psychosocial factors and mental health in Mexican women healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Saf. Health Work 2022, 13, S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaniego, A.; Urzúa, A.; Buenahora, M.; Vera-Villarroel, P. Sintomatología asociada a trastornos de salud mental en trabajadores sanitarios en Paraguay: Efecto COVID-19. [Symptomatology associated with mental health disorders in health care workers in Paraguay: The effect of COVID-19]. Interam. J. Psychol. 2020, 54, e1298. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Delgado, J.; Poblete, R.; Serpa, P.; Mula, A.; Carrillo, I.; Fernández, C.; Ripoll, V.; Loudet, C.; Jorro, F.; Elorrio, E.G.; et al. Contributing factors for acute stress in healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients in Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, V.; Belangero, W.; Godoy-Santos, A.L.; Pires, R.E.; Xicará, J.A.; Labronici, P.; Clinical Decision Rules (CDR) Study Group. The hidden impact of rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in professional, financial, and psychosocial health of Latin American orthopedic trauma surgeons. Injury 2021, 52, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.C.; Shanafelt, T.D.; West, C.P.; Sinsky, C.A.; Trockel, M.T.; Nedelec, L.; Maldonado, Y.A.; Tutty, M.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Fassiotto, M. Burnout, depression, career satisfaction, and work-life integration by physician race/ethnicity. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2012762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suñer-Soler, R.; Grau-Martín, A.; Flichtentrei, D.; Prats, M.; Braga, F.; Font-Mayolas, S.; Gras, M.A. The consequences of burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals in Spain and Spanish speaking Latin American countries. Burn. Res. 2014, 1, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.; Ribeiro, O.; Fonseca, A.M.; Carvalho, A.S. Burnout in intensive care units—A consideration of the possible prevalence and frequency of new risk factors: A descriptive correlational multicentre study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013, 13, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, A.F.; Andersen, C.M.; Olesen, F.; Vedsted, P. Risk of burnout in Danish GPs and exploration of factors associated with development of burnout: A two-wave panel study. Int. J. Fam. Med. 2013, 2013, 603713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.R.; Otero, P.; Blanco, V.; Ontaneda, M.P.; Díaz, O.; Vázquez, F.L. Prevalence and correlates of burnout in health professionals in Ecuador. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 82, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinueza-Veloz, A.; Aldaz-Pachacama, N.; Mera-Segovia, C.; Tapia-Veloz, E.; Vinueza-Veloz, M. Síndrome de Burnout en personal sanitario ecuatoriano durante la pandemia de la COVID-19. [Burnout Syndrome in Ecuadorian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic]. Corr. Cient. Med. 2021, 25, 2. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic and Financial Survey. Available online: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/weodata/index.aspx (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador. Registro Estadístico de Recursos y Actividades de Salud—RAS 2020 [Statistical Register of Health Resources and Activities—RAS 2020]. 2020. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Estadisticas_Sociales/Recursos_Actividades_de_Salud/RAS%1F_2020/Boletín_Técnico_RAS_2020.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador. Resultados del Censo de Ecuador [Results of the Ecuador Census]. 2023. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/estadisticas/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Ministry of Public Health. Plan decenal de Salud 2022–2031 [Ten-Year Health Plan]. 2022. Available online: https://www.salud.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Plan_decenal_Salud_2022_ejecutivo.18.OK_.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Hulley, S.B.; Newman, T.B.; Cummings, S.R. Choosing the study subjects: Specification, sampling and recruitment. In Designing Clinical Research, 4th ed.; Hulley, S.B., Cummings, S.R., Browner, W.R., Grady, D.G., Newman, T.B., Eds.; Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Seisdedos, N. MBI: Inventario Burnout de Maslach [MBI: Maslach Burnout Inventory]; Ediciones TEA: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladines-Costa, B.; López-Guerra, V.; Ruisoto, P.; Vaca-Gallegos, S.; Cacho, R. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Spanish version of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) in Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging 2004, 26, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucharte, A.; Calderón, L.; Cerezo, E.; Contreras, A.; Peinado, V. Three-item loneliness scale: Psychometric properties and normative data of the Spanish version. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 7466–7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.; Lovibond, S. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín, R.; Suria-Martínez, R.; López-López, M.D.L.; Vicent, M.; Gonzálvez, C.; García-Fernández, J.M. Validation, factorial invariance, and latent mean differences across sex of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-21) in Ecuadorian university sample. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2022, 53, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44 Pt 2, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar]

- International Test Commission. The ITC Guidelines Form Translating and Adapting Tests. 2017. Available online: https://www.intestcom.org/files/guideline_test_adaptation.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Dyrbye, L.N.; West, C.P.; Shanafelt, T.D. Defining burnout as a dichotomous variable. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.; Monette, G. Generalized collinearity diagnostics. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1992, 87, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. Applied Regression Analysis and Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Elphick, C.S. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, S.W.; Hickey, G.L.; Head, S.J. Statistical primer: Multivariable regression considerations and pitfalls. Eur. J. CardioThorac. Surg. 2019, 55, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Torre, M.; Ramos, M.A.; Rosales, R.C.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of burnout among physicians. A systematic review. JAMA 2018, 320, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Medical Association. Fatigue and Sleep Deprivation. The Impact of Different Working Patterns on Doctors; British Medical Association: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbluth, G.; Landrigan, C.P. Sleep, work hours, and medical performance. In Sleep, Health, and Society: From Aetiology to Public Health; Cappuccio, F.P., Miller, M.A., Lockley, S.W., Rajaratnam, S.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, E.; Looseley, A.; Mouton, R.; O’Connor, M.; Taylor, G.; Cook, T.M. Stress, burnout, depression and work satisfaction among UK anaesthetic trainees: A qualitative analysis of in-depth participant interviews in the satisfaction and wellbeing in anaesthetic training study. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, U.; Demerouti, E.; Bergström, G.; Samuelsson, M.; Ásberg, M.; Nygren, A. Burnout and physical and mental health among Swedish healthcare workers. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.S.; Rathert, C.; Buttigieg, S.C. The personal and professional consequences of physician burnout: A systematic review of the literature. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2020, 77, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yixuan, N.; Jie, F.J.; Ying, J.Z.; En, C.; Thumboo, J.; Khoon, H.; Xiang, Q. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on the well-being of healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen. Psychiatr. 2024, 37, e101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, D.; Mattick, K.; Pearson, M.; Papoutsi, C.; Briscoe, S.; Wong, G.; Jackson, M. Optimising strategies to address mental ill-health in doctors and medical students: ‘Care Under Pressure’ realist review and implementation guidance. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, R.I.H.; Yaow, C.Y.L.; Chong, N.Z.; Yap, N.L.X.; Hong, A.S.Y.; Ng, Q.X.; Tan, H.K. Scoping review of the second victim syndrome among surgeons: Understanding the impact, responses, and support systems. Am. J. Surg. 2024, 229, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Total | Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | |

| Sex Men Women | 952 (48.2) 1024 (51.8) | |||||

| Age | 37.1 (9.4) | 38.3 (10.0) | 36.0 (8.7) | |||

| Marital status Without partner With partner | 1029 (52.1) 947 (47.9) | 452 (47.5) 500 (52.5) | 577 (56.3) 447 (43.7) | |||

| Area of work Urban Rural | 1673 (84.7) 303 (15.3) | 816 (85.7) 136 (14.3) | 857 (83.7) 167 (16.3) | |||

| Sector in which they work Public Private/mixed | 1238 (62.7) 738 (37.3) | 560 (58.8) 392 (41.2) | 678 (66.2) 346 (33.8) | |||

| Type of contract Temporary Permanent | 1108 (56.1) 868 (43.9) | 501 (52.6) 451 (47.4) | 607 (59.3) 417 (40.7) | |||

| Appointment Part time Full time | 321 (16.2) 1655 (83.8) | 143 (15.0) 809 (85.0) | 178 (17.4) 846 (82.6) | |||

| Monthly income | 2828.1 (3445.7) | 2787.5 (3302.5) | 2865.7 (3574.8) | |||

| Professional experience | 9.6 (8.4) | 10.4 (8.9) | 8.9 (7.8) | |||

| Shifts No shifts With shifts | 802 (40.6) 1174 (59.4) | 367 (38.6) 585 (61.4) | 435 (42.5) 589 (57.5) | |||

| Daily workday | 10.5 (5.4) | 10.1 (5.0) | 10.8 (5.7) | |||

| Attend to patients at risk of death No Yes | 285 (14.4) 1691 (85.6) | 117 (12.3) 835 (87.7) | 168 (16.4) 856 (83.6) | |||

| Work–family conflicts No Yes | 658 (33.3) 1318 (66.7) | 328 (34.5) 624 (65.5) | 330 (32.2) 694 (67.8) | |||

| Psychological inflexibility | 16.6 (9.8) | 16.4 (9.7) | 16.9 (9.9) | |||

| Perceived loneliness | 5.1 (2.3) | 5.0 (2.3) | 5.2 (2.3) | |||

| Depression | 3.6 (4.3) | 3.6 (4.5) | 3.6 (4.1) | |||

| Anxiety | 3.9 (4.4) | 3.8 (4.4) | 4.0 (4.3) | |||

| Stress | 5.1 (4.6) | 4.9 (4.6) | 5.2 (4.5) | |||

| Variable | Total | Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Men n (%) | Women n (%) | |

| Emotional Exhaustion Subscale M (SD) Low Medium High | 18.7 (11.7) 1107 (56.0) 369 (18.7) 500 (25.3) | 18.3 (12.0) 538 (56.5) 179 (18.8) 235 (24.7) | 18.9 (11.4) 569 (55.6) 190 (18.6) 265 (25.9) |

| Depersonalization Subscale M (SD) Low Medium High | 6.0 (5.9) 1245 (63.0) 261 (13.2) 470 (23.8) | 6.7 (6.2) 553 (58.1) 141 (14.8) 258 (27.1) | 5.4 (5.6) 692 (67.6) 120 (11.7) 212 (20.7) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | (19) | (20) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional exhaustion | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Depersonalization | 0.63 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Sex (0 = Men;1 = Women) | 0.03 | −0.11 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Age | −0.18 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.12 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Marital status (0 = Without partner; 1 = With partner) | −0.13 ** | −0.14 | 0.09 ** | 0.34 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Area of work (0 = Urban; 1 = Rural) | 0.05 * | 0.05 * | 0.03 | −0.16 ** | 0.06 * | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 7. Sector in which they work (0 = Public; 1 = Private) | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 * | 0.11 ** | 0.02 | 0.19 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 8. Type of contract (0 = Temporary; 1 = Permanent) | −0.07 ** | −0.03 | 0.07 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.07 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 9. Appointment (0 =Full time; 1 = Part time) | −0.06 ** | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.06 * | 0.04 | 0.07 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.16 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 10. Income | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.05 * | −0.70 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.07 ** | 0.01 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 11. Professional experience | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.09 ** | 0.82 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.26 ** | −0.04 | −0.01 | 1 | |||||||||

| 12. Shifts (0 = No Shifts; 1 = With shifts) | 0.05 * | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | −0.16 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.01 | 0.10 ** | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.15 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 13. Daily workday | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.06 ** | −0.17 ** | 0.27 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.15 ** | 0.05 * | −0.06 ** | −0.03 | −0.17 ** | 0.37 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 14. Attend to patients at risk of death (0 = No; 1 = Yes) | 0.08 ** | 0.05 * | 0.06 ** | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.13 ** | 0.06 * | 0.08 ** | −0.04 | −0.06 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.15 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 15. Work–family conflicts | 0.33 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 * | 0.04 | −0.05 * | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.10 ** | 1 | |||||

| 16. Psychological inflexibility | 0.58 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.02 | −0.21 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.05 * | 0.01 | −0.09 ** | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.17 ** | 0.09 ** | −0.01 | 0.08 ** | 0.20 ** | 1 | ||||

| 17. Perceived loneliness | 0.49 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.03 | −0.14 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.07 ** | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.10 ** | 0.05 * | 0.01 | 0.05 * | 0.19 ** | 0.63 ** | 1 | |||

| 18. Depression | 0.55 ** | 0.53 ** | −0.01 | −0.17 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.07 ** | −0.03 | −0.08 ** | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.13 ** | 0.10 ** | −0.01 | 0.07 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.55 ** | 1 | ||

| 19. Anxiety | 0.55 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.02 | −0.14 ** | −0.11 ** | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.06 * | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.12 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.02 | 0.08 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.83 ** | 1 | |

| 20. Stress | 0.64 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.04 | −0.17 ** | −0.11 ** | 0.05 * | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.13 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.01 | 0.08 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.83 ** | 0.85 ** | 1 |

| Characteristic | Emotional Exhaustion | Depersonalization | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Standard Error | t | p | 95% CI a | β | Standard Error | t | p | 95% CI b | |

| Sex (0 = Men 1 = Women) | 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.986 | −0.81, 0.83 | −0.13 | 0.22 | −6.98 | <0.001 | −1.96, −1.10 |

| Marital status (0 = Without partner 1 = With partner) | −0.03 | 0.43 | −1.57 | 0.117 | −1.51, 0.17 | −0.04 | 0.23 | −1.84 | 0.065 | −0.88, 0.27 |

| Area of work (0 = Urban 1 = Rural) | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.22 | 0.828 | −1.10, 1.32 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 1.82 | 0.069 | −0.05, 1.19 |

| Sector in which they work (0 = Public 1 = Private) | −0.03 | 0.45 | −1.62 | 0.105 | −1.61, 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.58 | 0.563 | −0.32, 0.59 |

| Type of contract (0 = Temporary 1 = Permanent) | −0.02 | 0.43 | −1.30 | 0.194 | −1.41, 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.73 | 0.469 | −0.29, 0.63 |

| Appointment (0 = Full time 1 = Part time) | 0.05 | 0.58 | 2.80 | 0.005 | 0.48, 2.74 | −0.04 | 0.30 | −1.84 | 0.065 | −1.14, 0.04 |

| Monthly income | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.30 | 0.768 | −0.99, 1.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −1.52 | 0.128 | −0.98, 1.01 |

| Professional experience | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.68 | 0.496 | −0.07, 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −1.59 | 0.113 | −0.05, 0.01 |

| Shifts (0 = No Shifts 1 = With shifts) | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.701 | −1.10, 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 5.41 | <0.001 | 0.81, 1.73 |

| Daily workday | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.90 | 0.048 | 0.01, 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.81 | 0.070 | −0.08, 0.03 |

| Patients at risk of death (0 = No 1 = Yes) | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.530 | −0.81, 1.57 | −0.02 | 0.32 | −1.05 | 0.292 | −0.96, 0.29 |

| Work–family conflict (0 = No 1 = Yes) | 0.21 | 0.45 | 11.59 | <0.001 | 4.32, 6.08 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 3.26 | 0.001 | 0.31, 1.24 |

| Psychological inflexibility | 0.46 | 0.03 | 20.07 | <0.001 | 0.50, 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 17.51 | <0.001 | 0.23, 0.28 |

| Perceived loneliness | 0.11 | 0.12 | 4.74 | <0.001 | 0.32, 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 4.95 | <0.001 | 0.18, 0.42 |

| Characteristic | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Standard Error | t | p | 95% CI a | β | Standard Error | t | p | 95% CI b | β | Standard Error | t | p | 95% CI c | |

| Emotional Exhaustion | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.12 | 0.905 | −0.01, 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −1.46 | 0.144 | −0.02, 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 14.81 | <0.001 | 0.07, 0.09 |

| Depersonalization | 0.07 | 0.01 | 4.84 | <0.001 | 0.03, 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.07 | 0.284 | −0.10, 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.957 | −0.02, 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramírez, M.R.; Ontaneda, M.P.; Otero, P.; Ortega-Jiménez, D.; Blanco, V.; Vázquez, F.L. Burnout, Associated Factors, and Mental Health Measures Among Ecuadorian Physicians: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072465

Ramírez MR, Ontaneda MP, Otero P, Ortega-Jiménez D, Blanco V, Vázquez FL. Burnout, Associated Factors, and Mental Health Measures Among Ecuadorian Physicians: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(7):2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072465

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamírez, Marina R., Mercy P. Ontaneda, Patricia Otero, David Ortega-Jiménez, Vanessa Blanco, and Fernando L. Vázquez. 2025. "Burnout, Associated Factors, and Mental Health Measures Among Ecuadorian Physicians: A Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 7: 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072465

APA StyleRamírez, M. R., Ontaneda, M. P., Otero, P., Ortega-Jiménez, D., Blanco, V., & Vázquez, F. L. (2025). Burnout, Associated Factors, and Mental Health Measures Among Ecuadorian Physicians: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(7), 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072465