Comparative Safety Profiles of Biosimilars vs. Originators Used in Rheumatology: A Pharmacovigilance Analysis of the EudraVigilance Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

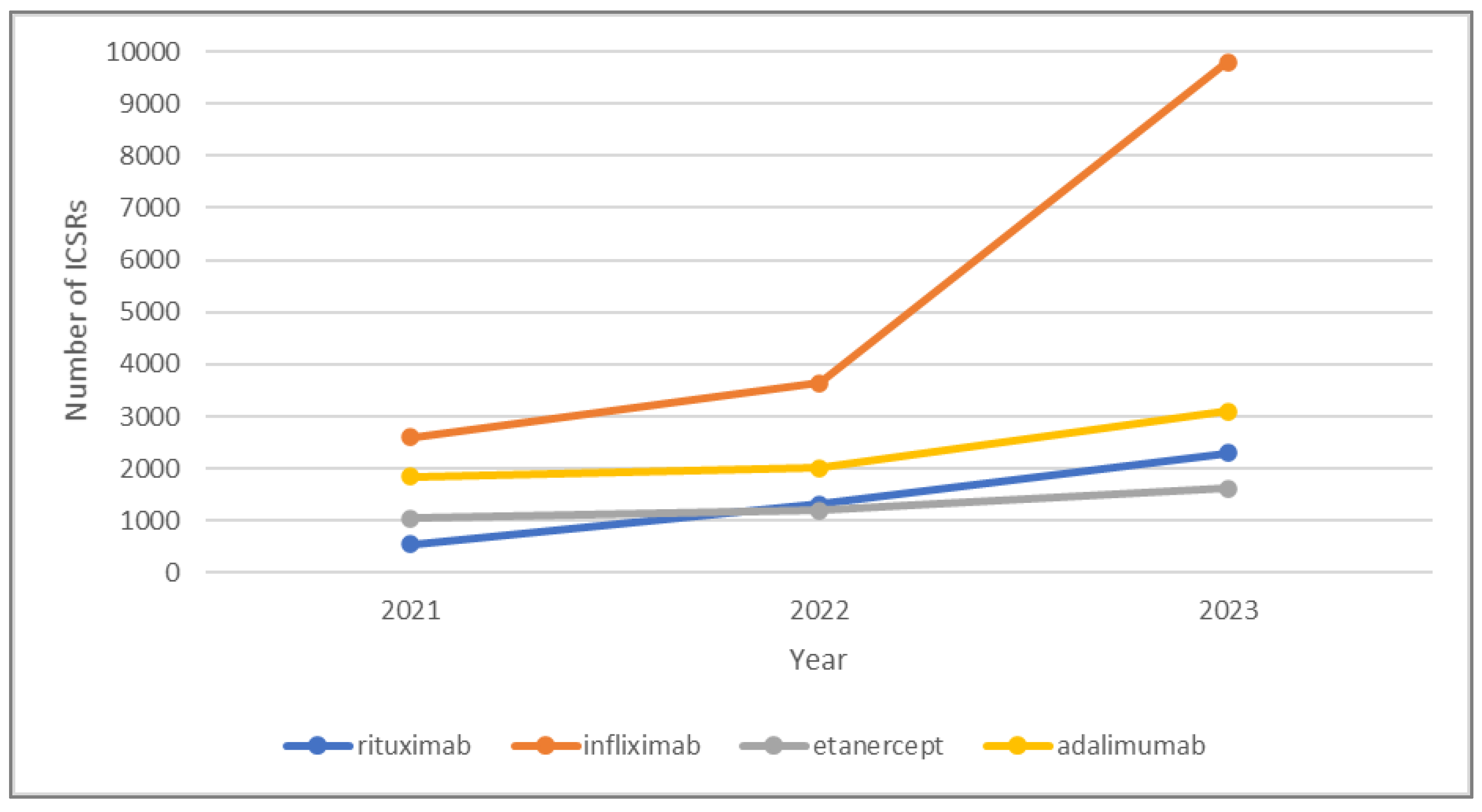

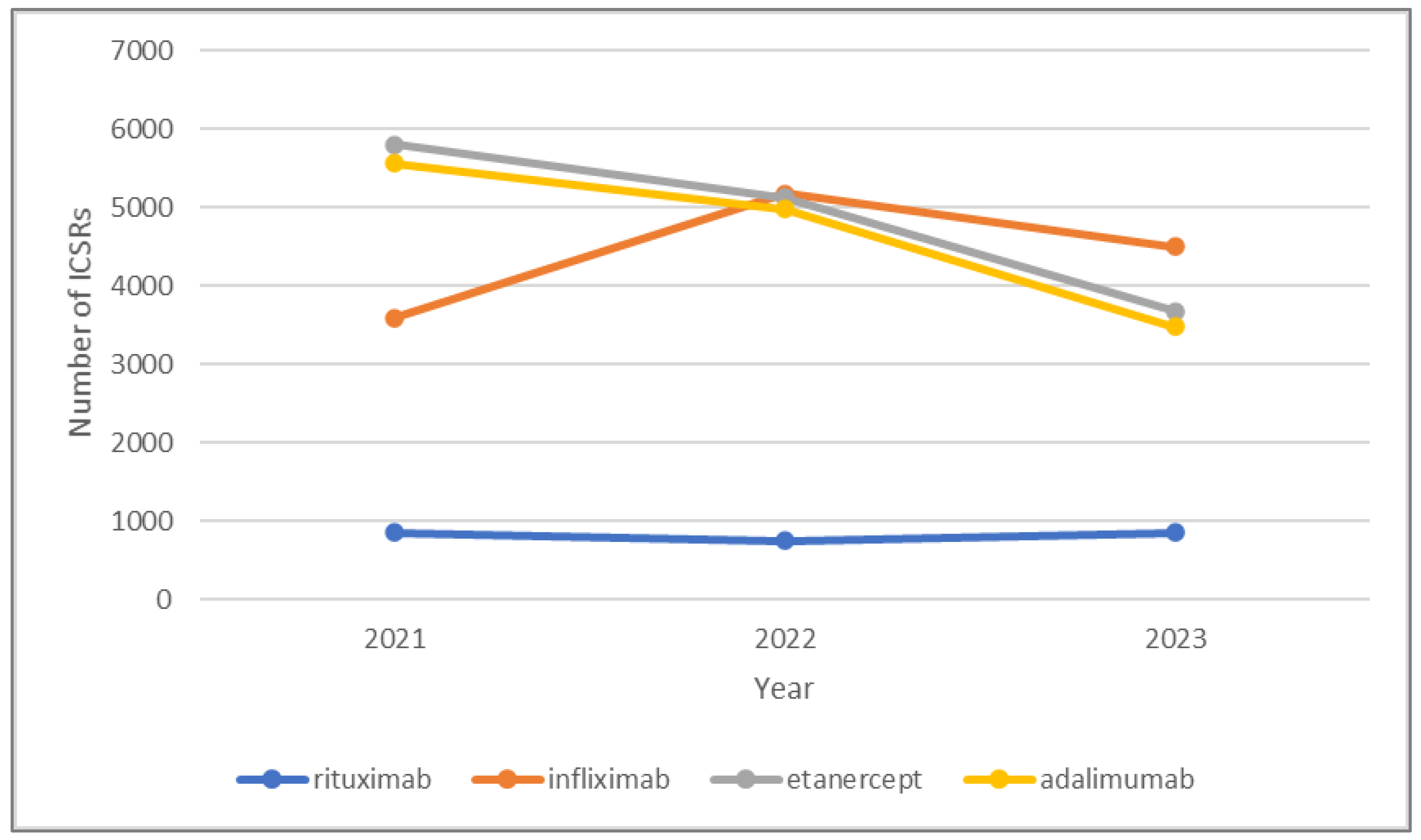

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADR | Adverse drug reaction |

| AE | Adverse event |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EU | European Union |

| EV | EudraVigilance |

| FDA | United States Food and Drug Administration |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| MedDRA | Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities |

| PTs | Preferred terms |

| RPs | Reference products |

| ROR | Reporting odds ratio |

| SPCs | Summary of Product Characteristics |

References

- Raychaudhuri, S.P.; Raychaudhuri, S.K. Biologics: Target-specific treatment of systemic and cutaneous autoimmune diseases. Indian J. Dermatol. 2009, 54, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A. Biological Drugs: Challenges to Access; Third World Network: Penang, Malaysia, 2018; pp. 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska, A. Biologics and Biosimilars: Background and Key Issues, R44620; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The European Medicines Agency. Human Regulatory. Biosimilar Medicines: Overview. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Food and Drug Administration. Biosimilars. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/therapeutic-biologics-applications-bla/biosimilars (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- The World Health Organization. Biosimilars. Guidelines on Evaluation of Biosimilars Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 977. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/biologicals/who_trs_1043_annex-3_biosimilars_tk.pdf?sfvrsn=998a85d_1&download=true (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products Containing Biotechnology-Derived Proteins as Active Substance: Non-Clinical and Clinical Issues. Available online: www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-biotechnology-derived-proteins-active_en-2.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products Containing Monoclonal Antibodies—Non-clinical and Clinical Issues. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-monoclonal-antibodies-non-clinical-and-clinical-issues_en.pdf. (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Kirchhoff, C.F.; Wang, X.Z.M.; Conlon, H.D.; Anderson, S.; Ryan, A.M.; Bose, A. Biosimilars: Key regulatory considerations and similarity assessment tools. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 2696–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buske, C.; Ogura, M.; Kwon, H.C.; Yoon, S.W. An introduction to biosimilar cancer therapeutics: Definitions, rationale for development and regulatory requirements. Future Oncol. 2017, 13, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humira ®, INN-Adalimumab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/humira-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Remicade®, INN-Infliximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/remicade-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- MabThera®, INN-Rituximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/mabthera-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Enbrel®, INN-Etanercept-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/enbrel-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Amgevita®, INN-Adalimumab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/amgevita-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Amsparity®, INN-Adalimumab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/amsparity-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Hulio®, INN-Adalimumab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/hulio-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Hyrimoz®, INN-Adalimumab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/hyrimoz-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Hefiya®, INN-Adalimumab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/hefiya-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Idacio®, INN-Adalimumab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/idacio-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Imraldi®, INN-Adalimumab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/imraldi-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Flixabi®, INN-Infliximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/flixabi-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Inflectra®, INN-Infliximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/inflectra-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Remsima®, INN-Infliximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/remsima-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Zessly®, INN-Infliximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/zessly-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Blitzima®, INN-Rituximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/blitzima-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Rixathon®, INN-Rituximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/rixathon-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Riximyo®, INN-Rituximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/riximyo-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Ruxience®, INN-Rituximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ruxience-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Truxima®, INN-Rituximab-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/truxima-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Benepali®, INN-Etanercept-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/benepali-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Erelzi®, INN-Etanercept-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/erelzi-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Nepexto®, INN-Etanercept-European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/nepexto-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- European Medicines Agency. Screening Adverse Reactions Eudravigilance. Important Medical Event. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/screening-adverse-reactions-eudravigilance_en.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Brasington, R.; Strand, V. New Treatments in Rheumatology: Biosimilars. Curr. Treat Options Rheum 2020, 6, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Biosimilars in the EU: Information Guide for Healthcare Professionals; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, G.; Wang, J.; Schwab, C.A.; Li, M.S. Barriers impeding the availability and uptake of biosimilars in the US. Value Health 2018, 21, S194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harston, A. How the U.S. Compares to Europe on Biosimilar Approvals and Products in the Pipeline. Updated May 16, 2022. Available online: https://www.biosimilarsip.com/2022/03/14/how-the-u-s-compares-to-europe-on-biosimilar-approvals-and-products-in-the-pipeline-updated-march-14-2022/ (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Quintero, O.L.; Amador-Patarroyo, M.J.; Montoya-Ortiz, G.; Rojas-Villarraga, A.; Anaya, J.M. Autoimmune disease and gender: Plausible mechanisms for the female predominance of autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2012, 38, J109–J119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, N.; Misra, S.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Verbeke, G.; Molenberghs, G.; Taylor, P.N.; Mason, J.; Sattar, N.; McMurray, J.J.V.; McInnes, I.B.; et al. Incidence, prevalence, and co-occurrence of autoimmune disorders over time and by age, sex, and socioeconomic status: A population-based cohort study of 22 million individuals in the UK. Lancet 2023, 401, 1878–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Suo, T.; Shen, Y.; Geng, C.; Song, Z.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, T.; et al. Clinicians versus patients subjective adverse events assessment: Based on patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 3009–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weise, M.; Marie-Christine Bielsky, M.C.; Karen De Smet, K.; Ehmann, F.; Ekman, N.; Giezen, T.J.; Gravanis, I.; Heim, H.K.; Heinonen, E.; Ho, K.; et al. Biosimilars: What clinicians should know. Blood 2012, 120, 5111–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giezen, T.; Schneider, C.K. Safety assessment of biosimilars in Europe: A regulatory perspective. GaBI J. 2014, 3, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giezen, T.J.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K.; Straus, S.M.J.M.; Schellekens, H.; Leufkens, H.G.; Egberts, A.C. Safety-related regulatory actions for biologicals approved in the United States and the European Union. JAMA 2008, 300, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Giezen, T.J.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K.; Meyboom, R.H.; Straus, S.M.; Leufkens, H.G.; Egberts, T.C. Mapping the safety profile of biologicals: A disproportionality analysis using the WHO adverse drug reaction database. VigiBase. Drug Saf. 2010, 33, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho Lee, Y.; Gyu Song, G. Comparative efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and their biosimilars in patients with rheumatoid arthritis having an insufficient response to methotrexate. Z. Rheumatol. 2023, 82, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascef, B.O.; Almeida, M.O.; Medeiros-Ribeiro, A.C.; de Andrade, D.C.O.; de Oliveira Junior, H.A.; de Soárez, P.C. Therapeutic Equivalence of Biosimilar and Reference Biologic Drugs in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 2023, 6, e2315872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezk, M.F.; Pieper, B. To See or NOsee: The Debate on the Nocebo Effect and Optimizing the Use of Biosimilars. Adv. Ther. 2018, 35, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Rao, N.A. Alopecia Areata During Etanercept Therapy. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2009, 17, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posten, W.; Swan, J. Recurrence of Alopecia Areata in a Patient Receiving Etanercept Injections. Arch. Dermatol. 2005, 141, 759–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurki, P.; Barry, S.; Bourges, I.; Tsantili, P.; Wolff-Holz, E. Safety, Immunogenicity and Interchangeability of Biosimilar Monoclonal Antibodies and Fusion Proteins: A Regulatory Perspective. Drugs 2021, 81, 1881–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spelsberg, A.; Prugger, C.; Doshi, P.; Ostrowski, K.; Witte, T.; Hüsgen, D.; Keil, U. Contribution of industry funded post-marketing studies to drug safety: Survey of notifications submitted to regulatory agencies. BMJ 2017, 356, j337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahović-Palčevski, V.; Mentzer, D. Postmarketing surveillance. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2011, 205, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouillon, L.; Socha, M.; Demore, B.; Thilly, N.; Abitbol, V.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. The nocebo effect: A clinical challenge in the era of biosimilars. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 14, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomar, M.; Tawfiq, A.M.; Hassan, N.; Palaian, S. Post marketing surveillance of suspected adverse drug reactions through spontaneous reporting: Current status, challenges and the future. Ther. Adv. Drug. Saf. 2020, 11, 2042098620938595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasford, J.; Goettler, M.; Munter, K.H.; Müller-Oerlinghausen, B. Physicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding the spontaneous reporting system for adverse drug reactions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2002, 55, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varallo, F.R.; Guimarães, S.D.; Abjaude, S.A.; Mastroianni, P.D. Causes for the underreporting of adverse drug events by health professionals: A systematic review. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2014, 48, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppsala Monitoring Centre. Signal Work. Available online: https://who-umc.org/signal-work/what-is-a-signal/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

| Regulatory Authority | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| The European Medicines Agency (EMA) | A biosimilar is a biological medicine highly similar to another already approved biological medicine (the ‘reference medicine’). Biosimilars are approved according to the same standards of pharmaceutical quality, safety and efficacy that apply to all biological medicines. | The European Medicines Agency. Biosimilar Medicines: Overview [4] |

| Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | A biosimilar is a biologic medication that is highly similar to and has no clinically meaningful differences from an existing FDA-approved biologic, called a reference product. | Food and Drug Administration. Biosimilars [5] |

| The World Health Organization (WHO) | A biotherapeutic product which is similar in terms of quality, safety and efficacy to an already licensed reference biotherapeutic product. | The World Health Organization. Biosimilars [6] |

| Reference Product | Authorization Date | Patent Expiry Date | Biosimilar Agent | Approval Date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab | Humira® | 2003 | 2018 | Amgevita® | 22 March 2017 |

| Amsparity® | 13 February 2020 | ||||

| Hulio® | 17 September 2018 | ||||

| Hyrimoz® | 26 July 2018 | ||||

| Hefiya® | 26 July 2018 | ||||

| Idacio® | 02 April 2019 | ||||

| Imraldi® | 24 August 2017 | ||||

| Rituximab | MabThera® | 1998 | 2013 | Blitzima® | 13 July 2017 |

| Rixathon® | 15 June 2017 | ||||

| Riximyo® | 15 June 2017 | ||||

| Ruxience® | 01 April 2020 | ||||

| Truxima® | 17 February 2017 | ||||

| Etanercept | Enbrel® | 2000 | 2015 | Benepali® | 14 January 2016 |

| Erelzi® | 23 June 2017 | ||||

| Nepexto® | 20 May 2020 | ||||

| Infliximab | Remicade® | 1999 | 2015 | Flixabi® | 26 May 2016 |

| Inflectra® | 10 September 2013 | ||||

| Remsima® | 10 September 2013 | ||||

| Zessly® | 18 May 2018 |

| Characteristics | Rituximab | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Originator Biologic MabThera® (n = 2451) | Biosimilar | ||||||

| Blitzima® (n = 9) | Rixathon® (n = 736) | Riximyo® (n = 78) | Ruxience® (n = 2329) | Truxima® (n = 1019) | |||

| Sex | Female | 1270 (51.8) | 2 (22.2) | 419 (56.9) | 59 (75.6) | 1578 (67.8) | 276 (27.1) |

| Male | 1135 (46.3) | 4 (44.4) | 299 (40.6) | 18 (23.1) | 736 (31.6) | 217 (21.3) | |

| Unknown | 46 (1.9) | 3 (33.3) | 18 (2.4) | 1 (1.3) | 15 (0.6) | 526 (51.6) | |

| Age (years) | 0–17 | 75 (3.1) | 1 (11.1) | 27 (3.7) | 2 (2.6) | 10 (0.4) | 22 (2.1) |

| 18–64 | 1114 (45.4) | 3 (33.3) | 369 (50.1) | 36 (46.1) | 1272 (54.6) | 329 (32.3) | |

| 65–85 | 791 (32.3) | 2 (22.2) | 246 (33.4) | 24 (30.8) | 961 (41.3) | 165 (16.2) | |

| >85 | 32 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.3) | 2 (2.6) | 52 (2.2) | 10 (1.0) | |

| Unknown | 439 (17.9) | 3 (33.3) | 78 (10.6) | 14 (17.9) | 34 (1.5) | 493 (48.4) | |

| Reporter type | Healthcare Professional | 2248 (91.7) | 9 (100) | 709 (96.3) | 75 (96.2) | 2235 (96.0) | 956 (93.8) |

| Non-healthcare Professional | 203 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (3.7) | 3 (3.8) | 94 (4.0) | 63 (6.2) | |

| Characteristics | Etanercept | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Originator Biologic Enbrel® (n = 14,588) | Biosimilar | ||||

| Benepali® (n = 1327) | Erelzi® (n = 2473) | Nepexto® (n = 69) | |||

| Sex | Female | 11,623 (79.7) | 901 (67.9) | 2003 (81.0) | 55 (79.7) |

| Male | 2675 (18.3) | 392 (29.5) | 426 (17.2) | 12 (17.4) | |

| Unknown | 290 (2.0) | 34 (2.6) | 44 (1.8) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Age (years) | 0–17 | 262 (1.8) | 13 (0.9) | 44 (1.8) | 3 (4.4) |

| 18–64 | 6744 (46.2) | 662 (49.9) | 1272 (51.4) | 29 (42.0) | |

| 65–85 | 3816 (26.2) | 305 (23.0) | 387 (15.6) | 21 (30.4) | |

| >85 | 168 (1.1) | 7 (0.5) | 16 (0.6) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Unknown | 3598 (24.7) | 340 (25.6) | 754 (30.5) | 15 (21.7) | |

| Reporter type | Healthcare Professional | 7412 (50.8) | 1010 (76.1) | 2203 (89.1) | 57 (82.6) |

| Non-healthcare Professional | 7176 (49.2) | 317 (23.9) | 270 (10.9) | 12 (17.4) | |

| Characteristics | Adalimumab | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Originator Biologic Humira® (n = 14,002) | Biosimilar | |||||

| Amgevita® (n = 1835) | Amsparity® (n = 23) | Hefiya® (n = 10) | Hukyndra® (n = 28) | |||

| Sex | Female | 9689 (69.2) | 1106 (60.3) | 16 (69.6) | 8 (80.0) | 22 (78.6) |

| Male | 3845 (27.5) | 700 (38.1) | 6 (26.1) | 2 (20.0) | 6 (21.4) | |

| Unknown | 468 (3.3) | 29 (1.6) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Age (years) | 0–17 | 435 (3.1) | 48 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.) | 0 (0.0) |

| 18–64 | 6574 (47.0) | 958 (52.2) | 14 (60.9) | 4 (40.0) | 16 (57.1) | |

| 65–85 | 1812 (12.9) | 226 (12.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.) | 7 (30.4) | |

| >85 | 58 (0.4) | 7 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 5123 (36.6) | 596 (32.5) | 9 (39.1) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Reporter type | Healthcare Professional | 9328 (66.6) | 1205 (65.7) | 18 (78.3) | 5 (50.0) | 22 (78.6) |

| Non-healthcare Professional | 4674 (33.4) | 630 (34.3) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (50.0) | 6 (21.4) | |

| Characteristics | Adalimumab | |||||

| Biosimilar | ||||||

| Hulio® (n = 304) | Hyrimoz® (n = 2200) | Idacio® (n = 634) | Imraldi® (n = 1424) | Yuflyma® (n = 498) | ||

| Sex | Female | 183 (60.2) | 1258 (57.2) | 402 (63.4) | 881 (61.9) | 322 (64.7) |

| Male | 114 (37.5) | 835 (38.0) | 219 (34.5) | 517 (36.3) | 164 (32.9) | |

| Unknown | 7 (2.3) | 107 (4.9) | 13 (2.1) | 26 (1.8) | 12 (2.4) | |

| Age (years) | 0–17 | 6 (2.0) | 45 (2.0) | 9 (1.4) | 17 (1.2) | 7 (1.4) |

| 18–64 | 179 (58.9) | 1405 (63.9) | 447 (70.5) | 1002 (70.4) | 345 (69.3) | |

| 65–85 | 49 (16.1) | 268 (12.2) | 94 (14.8) | 187 (13.1) | 57 (11.4) | |

| >85 | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Unknown | 70 (23.0) | 472 (21.5) | 84 (13.2) | 213 (15.0) | 87 (17.5) | |

| Reporter type | Healthcare Professional | 234 (77.0) | 1869 (85.0) | 490 (77.3) | 1188 (83.4) | 334 (67.1) |

| Non-healthcare Professional | 70 (23.0) | 331 (15.0) | 144 (22.7) | 236 (16.6) | 164 (32.9) | |

| Characteristics | Infliximab | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Originator Biologic Remicade® (n = 13,248) | Biosimilar | |||||

| Flixabi® (n = 592) | Inflectra® (n = 12,462) | Remsima® (n = 2563) | Zessly® (n = 425) | |||

| Sex | Female | 8166 (61.6) | 306 (51.7) | 6453 (51.8) | 1234 (48.1) | 188 (44.2) |

| Male | 4759 (35.9) | 277 (46.8) | 5736 (46.0) | 816 (31.8) | 221 (52.0) | |

| Unknown | 323 (2.4) | 9 (1.5) | 273 (2.2) | 513 (20.0) | 16 (3.8) | |

| Age (years) | 0–17 | 335 (2.5) | 45 (7.6) | 191 (1.5) | 71 (2.8) | 17 (4.0) |

| 18–64 | 8323 (62.8) | 469 (79.2) | 9761 (78.3) | 1368 (53.4) | 308 (72.5) | |

| 65–85 | 1744 (13.2) | 46 (7.8) | 2007 (16.1) | 212 (8.3) | 44 (10.4) | |

| >85 | 68 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 69 (0.6) | 5 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Unknown | 2778 (21.0) | 31 (5.2) | 434 (3.5) | 907 (35.4) | 55 (12.9) | |

| Reporter type | Healthcare Professional | 11,913 (89.9) | 416 (70.3) | 11,978 (96.1) | 1892 (73.8) | 405 (95.3) |

| Non-healthcare Professional | 1335 (10.1) | 176 (29.7) | 484 (3.9) | 671 (26.2) | 20 (4.7) | |

| Adalimumab | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | N | N* | ROR | CI 95%_Lower | CI 95%_Upper |

| Drug ineffective | 838 | 5067 | 1.20 | 1.12 | 1.28 |

| Injection site pain | 450 | 342 | 9.70 | 8.79 | 10.70 |

| Arthralgia | 440 | 2095 | 1.52 | 1.39 | 1.67 |

| Psoriasis | 396 | 587 | 4.94 | 4.46 | 5.47 |

| Pruritus | 231 | 344 | 4.88 | 4.26 | 5.58 |

| Headache | 223 | 989 | 1.63 | 1.43 | 1.86 |

| Arthritis | 218 | 530 | 2.98 | 2.60 | 3.42 |

| Condition aggravated | 200 | 1224 | 1.18 | 1.02 | 1.35 |

| Loss of therapeutic response | 146 | 35 | 30.23 | 24.30 | 37.61 |

| Product substitution issue | 141 | 8 | 127.72 | 84.75 | 192.50 |

| COVID-19 | 138 | 394 | 2.53 | 2.13 | 3.00 |

| Urticaria | 137 | 233 | 4.25 | 3.57 | 5.07 |

| Erythema | 133 | 323 | 2.97 | 2.49 | 3.55 |

| Psoriatic arthropathy | 125 | 479 | 1.88 | 1.57 | 2.25 |

| Skin exfoliation | 113 | 52 | 15.71 | 12.58 | 19.62 |

| Pyrexia | 111 | 433 | 1.85 | 1.53 | 2.24 |

| Crohn’s disease | 106 | 575 | 1.33 | 1.09 | 1.61 |

| Dizziness | 105 | 334 | 2.27 | 1.86 | 2.76 |

| Abdominal pain | 105 | 476 | 1.59 | 1.31 | 1.93 |

| Malaise | 104 | 611 | 1.22 | 1.01 | 1.49 |

| Asthenia | 99 | 374 | 1.91 | 1.56 | 2.33 |

| Dyspnea | 99 | 453 | 1.57 | 1.29 | 1.92 |

| Back pain | 97 | 347 | 2.01 | 1.64 | 2.47 |

| Therapy non-responder | 94 | 126 | 5.38 | 4.33 | 6.70 |

| Injection site erythema | 94 | 177 | 3.83 | 3.10 | 4.74 |

| Paraesthesia | 84 | 143 | 4.24 | 3.37 | 5.32 |

| Myalgia | 80 | 157 | 3.67 | 2.91 | 4.63 |

| Cough | 79 | 182 | 3.13 | 2.48 | 3.94 |

| Vomiting | 61 | 316 | 1.39 | 1.07 | 1.80 |

| Anxiety | 58 | 216 | 1.93 | 1.48 | 2.52 |

| Etanercept | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | N | N* | ROR | CI 95%_Lower | CI 95%_Upper |

| Fatigue | 685 | 2190 | 1.17 | 1.09 | 1.26 |

| Alopecia | 615 | 1720 | 1.34 | 1.24 | 1.45 |

| Arthropathy | 551 | 1680 | 1.23 | 1.13 | 1.34 |

| Abdominal discomfort | 541 | 1662 | 1.22 | 1.12 | 1.33 |

| Glossodynia | 471 | 1227 | 1.44 | 1.31 | 1.58 |

| Condition aggravated | 429 | 1297 | 1.24 | 1.12 | 1.36 |

| Injection site pain | 374 | 283 | 4.98 | 4.47 | 5.55 |

| Pemphigus | 372 | 1250 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 1.23 |

| Hand deformity | 370 | 1114 | 1.24 | 1.12 | 1.38 |

| Product use issue | 353 | 845 | 1.57 | 1.41 | 1.74 |

| Discomfort | 350 | 830 | 1.58 | 1.42 | 1.76 |

| Infusion-related reaction | 312 | 865 | 1.35 | 1.21 | 1.51 |

| General physical health deterioration | 295 | 434 | 2.55 | 2.27 | 2.87 |

| Musculoskeletal stiffness | 289 | 803 | 1.35 | 1.20 | 1.51 |

| Psoriatic arthropathy | 275 | 551 | 1.87 | 1.66 | 2.11 |

| Maternal exposure during pregnancy | 273 | 868 | 1.18 | 1.04 | 1.33 |

| Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody positive | 270 | 685 | 1.48 | 1.31 | 1.67 |

| C-reactive protein increased | 229 | 445 | 1.93 | 1.69 | 2.20 |

| Blister | 226 | 734 | 1.15 | 1.01 | 1.31 |

| Blood cholesterol increased | 211 | 379 | 2.09 | 1.81 | 2.40 |

| Arthritis | 209 | 469 | 1.67 | 1.45 | 1.92 |

| Confusional state | 207 | 618 | 1.25 | 1.09 | 1.44 |

| Liver injury | 202 | 233 | 3.25 | 2.81 | 3.76 |

| Duodenal ulcer perforation | 175 | 424 | 1.54 | 1.32 | 1.80 |

| Helicobacter infection | 159 | 434 | 1.37 | 1.17 | 1.61 |

| Product use in unapproved indication | 155 | 141 | 4.12 | 3.47 | 4.89 |

| Psoriasis | 153 | 222 | 2.58 | 2.18 | 3.05 |

| Exposure during pregnancy | 152 | 234 | 2.43 | 2.06 | 2.87 |

| Dizziness | 152 | 256 | 2.22 | 1.88 | 2.63 |

| Intentional product use issue | 150 | 411 | 1.36 | 1.16 | 1.61 |

| Infliximab | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | N | N* | ROR | CI 95%_Lower | CI 95%_Upper |

| Off-label use | 10,028 | 5703 | 1.33 | 1.31 | 1.36 |

| Condition aggravated | 7281 | 3110 | 1.78 | 1.74 | 1.83 |

| Intentional product use issue | 6020 | 2428 | 1.88 | 1.84 | 1.93 |

| Inappropriate schedule of product administration | 4449 | 1322 | 2.56 | 2.48 | 2.64 |

| Arthralgia | 3439 | 1942 | 1.33 | 1.28 | 1.37 |

| COVID-19 | 2173 | 559 | 2.93 | 2.80 | 3.06 |

| Weight increased | 2086 | 1035 | 1.51 | 1.44 | 1.58 |

| Malaise | 2006 | 771 | 1.95 | 1.86 | 2.04 |

| Weight decreased | 1913 | 808 | 1.77 | 1.69 | 1.86 |

| Blood pressure increased | 1646 | 515 | 2.40 | 2.28 | 2.53 |

| Headache | 1628 | 1003 | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.27 |

| Nausea | 1544 | 812 | 1.42 | 1.35 | 1.50 |

| Cough | 1292 | 336 | 2.88 | 2.71 | 3.06 |

| Therapeutic response shortened | 1248 | 152 | 6.16 | 5.76 | 6.60 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 1230 | 392 | 2.35 | 2.21 | 2.50 |

| Blood pressure fluctuation | 1188 | 396 | 2.25 | 2.11 | 2.39 |

| Heart rate decreased | 1184 | 345 | 2.57 | 2.41 | 2.74 |

| Pruritus | 1152 | 454 | 1.90 | 1.78 | 2.02 |

| Incorrect dose administered | 1133 | 346 | 2.45 | 2.30 | 2.61 |

| Dyspnoea | 1099 | 584 | 1.41 | 1.32 | 1.50 |

| Pyrexia | 1089 | 468 | 1.74 | 1.63 | 1.85 |

| Abdominal pain | 951 | 631 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 1.20 |

| Erythema | 937 | 371 | 1.89 | 1.76 | 2.02 |

| Dizziness | 930 | 397 | 1.75 | 1.63 | 1.88 |

| Drug level decreased | 828 | 98 | 6.33 | 5.79 | 6.91 |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 826 | 203 | 3.04 | 2.82 | 3.29 |

| Drug level below therapeutic | 809 | 194 | 3.12 | 2.88 | 3.38 |

| Vomiting | 804 | 374 | 1.61 | 1.49 | 1.73 |

| Asthenia | 740 | 374 | 1.48 | 1.37 | 1.60 |

| Back pain | 700 | 266 | 1.97 | 1.81 | 2.13 |

| Rituximab | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | N | N* | ROR | CI 95%_Lower | CI 95%_Upper |

| Off-label use | 2064 | 382 | 1.75 | 1.67 | 1.84 |

| Intentional product use issue | 590 | 31 | 6.04 | 5.23 | 6.98 |

| Condition aggravated | 340 | 8 | 13.37 | 9.40 | 19.00 |

| COVID-19 | 337 | 58 | 1.81 | 1.57 | 2.09 |

| Pruritus | 320 | 59 | 1.69 | 1.46 | 1.95 |

| Throat irritation | 290 | 14 | 6.49 | 5.03 | 8.38 |

| Nausea | 261 | 59 | 1.37 | 1.18 | 1.61 |

| Headache | 259 | 23 | 3.52 | 2.86 | 4.33 |

| Malaise | 258 | 11 | 7.34 | 5.44 | 9.92 |

| Fatigue | 245 | 32 | 2.39 | 1.98 | 2.88 |

| Inappropriate schedule of product administration | 243 | 2 | 38.07 | 12.59 | 115.07 |

| Blood pressure fluctuation | 210 | 2 | 32.85 | 10.76 | 100.23 |

| Hypertension | 206 | 43 | 1.49 | 1.24 | 1.79 |

| Pain | 199 | 15 | 4.14 | 3.16 | 5.42 |

| Cough | 199 | 25 | 2.48 | 1.99 | 3.08 |

| Blood pressure increased | 196 | 42 | 1.45 | 1.20 | 1.75 |

| Product use issue | 194 | 2 | 30.32 | 9.88 | 93.03 |

| Erythema | 178 | 30 | 1.84 | 1.49 | 2.28 |

| Arthralgia | 172 | 20 | 2.68 | 2.09 | 3.43 |

| Dizziness | 144 | 24 | 1.86 | 1.46 | 2.38 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 118 | 9 | 4.08 | 2.74 | 6.08 |

| Urticaria | 114 | 23 | 1.54 | 1.17 | 2.01 |

| Weight decreased | 103 | 10 | 3.20 | 2.17 | 4.73 |

| Blood pressure systolic increased | 93 | 1 | 28.93 | 3.32 | 251.74 |

| Throat tightness | 91 | 7 | 4.04 | 2.48 | 6.57 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 90 | 5 | 5.59 | 3.07 | 10.18 |

| Pain in extremity | 90 | 7 | 3.99 | 2.45 | 6.50 |

| Ear pruritus | 88 | 2 | 13.68 | 4.16 | 44.94 |

| Illness | 86 | 3 | 8.91 | 3.75 | 21.16 |

| Weight increased | 84 | 7 | 3.73 | 2.27 | 6.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nikitina, V.; Laurini, G.S.; Montanaro, N.; Motola, D. Comparative Safety Profiles of Biosimilars vs. Originators Used in Rheumatology: A Pharmacovigilance Analysis of the EudraVigilance Database. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051644

Nikitina V, Laurini GS, Montanaro N, Motola D. Comparative Safety Profiles of Biosimilars vs. Originators Used in Rheumatology: A Pharmacovigilance Analysis of the EudraVigilance Database. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(5):1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051644

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikitina, Victoria, Greta Santi Laurini, Nicola Montanaro, and Domenico Motola. 2025. "Comparative Safety Profiles of Biosimilars vs. Originators Used in Rheumatology: A Pharmacovigilance Analysis of the EudraVigilance Database" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 5: 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051644

APA StyleNikitina, V., Laurini, G. S., Montanaro, N., & Motola, D. (2025). Comparative Safety Profiles of Biosimilars vs. Originators Used in Rheumatology: A Pharmacovigilance Analysis of the EudraVigilance Database. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(5), 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051644