Partner Ethnicity and Assisted Reproductive Technology Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

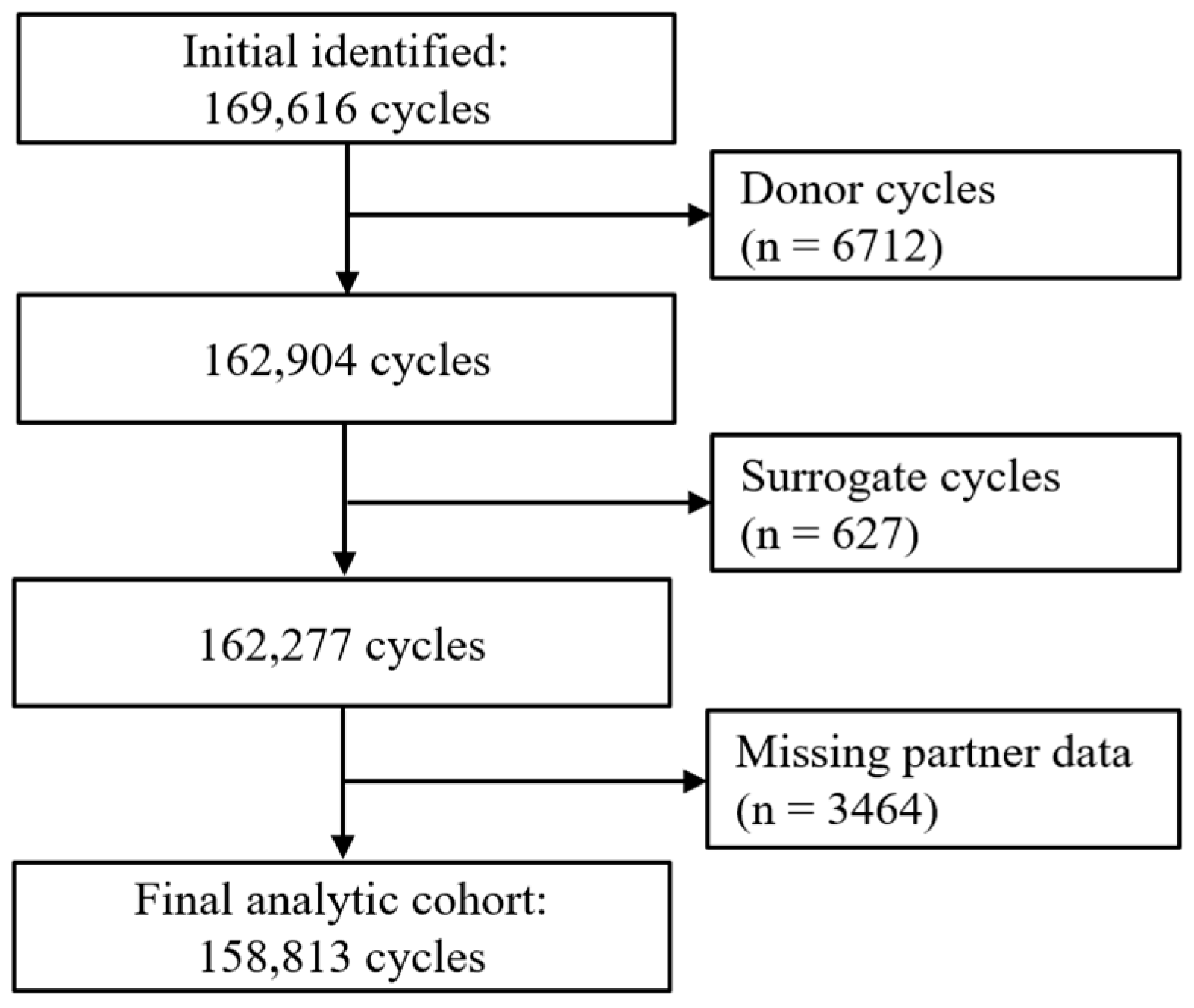

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Exposure

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Cycle Characteristics

3.3. Association Between Partner Ethnicity and IVF Outcomes

3.4. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fauser, B.C.J.M.; Adamson, G.D.; Boivin, J.; Chambers, G.M.; de Geyter, C.; Dyer, S.; Inhorn, M.C.; Schmidt, L.; Serour, G.I.; Tarlatzis, B.; et al. Declining Global Fertility Rates and the Implications for Family Planning and Family Building: An IFFS Consensus Document Based on a Narrative Review of the Literature. Hum. Reprod. Update 2024, 30, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.L.; Royston, P.; Campbell, S.; Jacobs, H.S.; Betts, J.; Mason, B.; Edwards, R.G. Cumulative Conception and Livebirth Rates after In-Vitro Fertilisation. Lancet 1992, 339, 1390–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A.G.; Shah, D.K.; Leonis, R.; Rees, J.; Correia, K.F.B. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive Medicine in the United States: A Narrative Review of Contemporary High-Quality Evidence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 232, 82–91.e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veira, P.; Wei, S.Q.; Ukah, U.V.; Healy-Profitós, J.; Auger, N. Black-White Inequality in Outcomes of in Vitro Fertilization: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 1974–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyward, Q.; Walter, J.R.; Alur-Gupta, S.; Lal, A.; Berger, D.S.; Koelper, N.; Butts, S.F.; Gracia, C.R. Racial disparities in frozen embryo transfer success. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 3069–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf, W.; Maalouf, W.; Campbell, B.; Jayaprakasan, K. Effect of Ethnicity on Live Birth Rates after in Vitro Fertilisation/Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Treatment: Analysis of UK National Database. BJOG 2017, 124, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, R.; Elbardisi, H.; Majzoub, A.; Arafa, M. Racial differences in male fertility parameters in 2996 men examined for infertility in a single center. Arab J. Urol. 2025, 23, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punjani, N.; Nayan, M.; Jarvi, K.; Lo, K.; Lau, S.; Grober, E.D. The Effect of Ethnicity on Semen Analysis and Hormones in the Infertile Patient. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2020, 14, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feferkorn, I.; Azani, L.; Kadour-Peero, E.; Hizkiyahu, R.; Shrem, G.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Dahan, M.H. Geographic Variation in Semen Parameters from Data Used for the World Health Organization Semen Analysis Reference Ranges. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vest, A.N.; Kipling, L.M.; Hipp, H.S.; Kawwass, J.F.; Mehta, A. Influence of Male Partner Race on Use and Outcomes of Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, e239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HFEA. UK Fertility Regulator. Available online: https://www.hfea.gov.uk/about-us/publications/research-and-data/ethnic-diversity-in-fertility-treatment-2018/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Zegers-Hochschild, F.; Adamson, G.D.; Dyer, S.; Racowsky, C.; de Mouzon, J.; Sokol, R.; Rienzi, L.; Sunde, A.; Schmidt, L.; Cooke, I.D.; et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1786–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Z.; Rucker, L.; Owen, J.; Wiltshire, A.; Kendall, L.; Edmonds, J.; Gunn, D. Investigation of Racial Disparities in Semen Parameters among White, Black, and Asian Men. Andrology 2021, 9, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vest, A.N.; Kipling, L.M.; Patil, D.; Hipp, H.S.; Kawwass, J.F.; Mehta, A. Influence of Paternal Race on Characteristics and Outcomes of Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Urology 2022, 163, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, I.; Lacey, L.; Akhtar, M.A.; Quenby, S. Ethnic Group and Reason for Assisted Reproductive Technology Failure: Analysis of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority Registry Data from 2017 to 2018. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handal-Orefice, R.C.; McHale, M.; Friedman, A.M.; Politch, J.A.; Kuohung, W. Impact of Race versus Ethnicity on Infertility Diagnosis between Black American, Haitian, African, and White American Women Seeking Infertility Care: A Retrospective Review. FS Rep. 2022, 3, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.B.; Jarvi, K.A.; Lajkosz, K.; Smith, J.F.; Lo, K.C.; Grober, E.D.; Lau, S.; Bieniek, J.M.; Brannigan, R.E.; Chow, V.D.W.; et al. One Size Does Not Fit All: Variations by Ethnicity in Demographic Characteristics of Men Seeking Fertility Treatment across North America. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltsas, A.; Zikopoulos, A.; Vrachnis, D.; Skentou, C.; Symeonidis, E.N.; Dimitriadis, F.; Stavros, S.; Chrisofos, M.; Sofikitis, N.; Vrachnis, N.; et al. Advanced Paternal Age in Focus: Unraveling Its Influence on Assisted Reproductive Technology Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahimer, M.; Montjean, D.; Cabry, R.; Capelle, S.; Lefranc, E.; Bach, V.; Ajina, M.; Ben Ali, H.; Khorsi-Cauet, H.; Benkhalifa, M. Paternal Age Matters: Association with Sperm Criteria’s-Spermatozoa DNA Integrity and Methylation Profile. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.L.; Dunleavy, J.; Gemmell, N.J.; Nakagawa, S. Consistent Age-Dependent Declines in Human Semen Quality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 19, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelisse, S.; Zagers, M.; Kostova, E.; Fleischer, K.; van Wely, M.; Mastenbroek, S. Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidies (Abnormal Number of Chromosomes) in in Vitro Fertilisation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, CD005291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yan, J.; Zhou, H.; Gong, F.; Zhang, A.; Wang, Z.; Jin, L.; Bao, H.; et al. Frozen versus Fresh Embryo Transfer in Women with Low Prognosis for in Vitro Fertilisation Treatment: Pragmatic, Multicentre, Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2025, 388, e081474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. Cycles (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 106,920) | Black (n = 3781) | Asian (n = 15,018) | Other (n = 33,094) | |

| Partner age, years | ||||

| 18–34 | 34,798 (32.6) | 772 (20.4) | 4965 (33.1) | 7643 (23.1) |

| 35–39 | 35,175 (32.9) | 1106 (29.3) | 5441 (36.2) | 9032 (27.3) |

| ≥40 | 36,947 (34.5) | 1903 (50.3) | 4612 (30.7) | 16,419 (49.6) |

| Female age, years | ||||

| 18–34 | 44,785 (41.9) | 1410 (37.3) | 7498 (49.9) | 12,475 (37.7) |

| 35–39 | 40,605 (38.0) | 1352 (35.8) | 5127 (34.2) | 12,829 (38.8) |

| ≥40 | 21,530 (20.1) | 1019 (26.9) | 2393 (15.9) | 7790 (23.5) |

| Female ethnicity | ||||

| White | 97,145 (90.9) | 828 (21.9) | 1299 (8.7) | 10,011 (30.2) |

| Black | 924 (0.8) | 2577 (68.2) | 30 (0.2) | 455 (1.4) |

| Asian | 2525 (2.3) | 78 (2.0) | 12,947 (86.2) | 1193 (3.6) |

| Other | 6326 (5.9) | 298 (7.9) | 742 (4.9) | 21,435 (64.8) |

| Partner type | ||||

| Male | 98,075 (91.7) | 3695 (97.7) | 14,907 (99.3) | 32,309 (97.6) |

| Female | 8845 (8.3) | 86 (2.3) | 111 (0.7) | 785 (2.4) |

| Gravidity | ||||

| 0 | 86,850 (81.2) | 3141 (83.1) | 12,463 (83.0) | 27,010 (81.6) |

| ≥1 | 20,070 (18.8) | 640 (16.9) | 2555 (17.0) | 6084 (18.4) |

| Infertility diagnosis | ||||

| Male factor | 36,767 (34.4) | 1289 (34.1) | 4930 (32.8) | 8688 (26.2) |

| Ovulatory disorder | 8197 (7.7) | 337 (8.9) | 1791 (11.9) | 2164 (6.5) |

| Tubal disease | 7661 (7.2) | 501 (13.3) | 928 (6.2) | 1847 (5.6) |

| Endometriosis | 3675 (3.4) | 102 (2.7) | 524 (3.5) | 946 (2.9) |

| Unexplained | 50,620 (47.3) | 1552 (41.0) | 6845 (45.6) | 19,449 (58.8) |

| No. Cycles (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 106,920) | Black (n = 3781) | Asian (n = 15,018) | Other (n = 33,094) | |

| Oocytes retrieved | ||||

| 0 | 45,528 (42.6) | 1636 (43.3) | 5709 (38.0) | 14,515 (43.9) |

| 1 to 5 | 16,565 (15.5) | 668 (17.7) | 2434 (16.2) | 4919 (14.9) |

| 6 to 10 | 20,375 (19.1) | 595 (15.7) | 3025 (20.1) | 5633 (17.0) |

| 11 to 15 | 13,506 (12.6) | 451 (11.9) | 2086 (13.9) | 4175 (12.6) |

| ≥16 | 10,946 (10.2) | 431 (11.4) | 1764 (11.8) | 3852 (11.6) |

| Total embryo created | ||||

| 0 | 46,072 (43.1) | 1717 (45.4) | 6197 (41.3) | 16,216 (49.0) |

| 1 to 5 | 32,502 (30.4) | 1192 (31.5) | 4750 (31.6) | 8762 (26.5) |

| ≥6 | 28,346 (26.5) | 872 (23.1) | 4071 (27.1) | 8116 (24.5) |

| Total embryos thawed | ||||

| 0 | 74,389 (69.6) | 2520 (66.6) | 10,318 (68.7) | 22,843 (69.0) |

| 1 to 5 | 31,858 (29.8) | 1231 (32.6) | 4556 (30.3) | 10,102 (30.5) |

| ≥6 | 673 (0.6) | 30 (0.8) | 144 (1.0) | 149 (0.5) |

| Cycle types | ||||

| Fresh cycle | 74,565 (69.7) | 2523 (66.7) | 10,346 (68.9) | 22,896 (69.2) |

| Frozen cycle | 32,355 (30.3) | 1258 (33.3) | 46,72 (31.1) | 10,198 (30.8) |

| Stimulation used | ||||

| Yes | 65,329 (61.1) | 2196 (58.1) | 9570 (63.7) | 20,035 (60.5) |

| No | 41,591 (38.9) | 1585 (41.9) | 5448 (36.3) | 13,059 (39.5) |

| Treatment type | ||||

| ICSI | 39,973 (37.4) | 1590 (40.1) | 5966 (39.7) | 13,154 (39.8) |

| IVF | 66,947 (62.6) | 2191 (57.9) | 9052 (60.3) | 19,940 (60.2) |

| eSET | ||||

| Yes | 36,823 (34.4) | 982 (26.0) | 4963 (33.1) | 9234 (27.9) |

| No | 70,097 (65.6) | 2799 (74.0) | 10,055 (66.9) | 23,860 (72.1) |

| PGT-A treatment | ||||

| Yes | 1322 (1.2) | 28 (0.7) | 161 (1.1) | 407 (1.2) |

| No | 105,598 (98.8) | 3753 (99.3) | 14,857 (99.9) | 32,687 (98.8) |

| Number of prior cycles | ||||

| 0 | 44,453 (41.6) | 1558 (41.2) | 6056 (40.3) | 13,851 (41.9) |

| 1 | 25,983 (24.3) | 980 (25.9) | 3905 (26.0) | 7821 (23.6) |

| 2 | 15,451 (14.5) | 567 (15.0) | 2260 (15.1) | 4803 (14.5) |

| ≥3 | 21,033 (19.6) | 676 (17.9) | 2797 (18.6) | 6619 (20.0) |

| Total No. | No. Events | Rate per 100 Cycles | Model 1 a | Model 2 b | Model 3 c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical pregnancy | ||||||

| White | 106,920 | 37,728 | 35.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Non-White | 51,893 | 16,474 | 31.7 | 0.90 (0.89–0.91) | 0.92 (0.91–0.94) | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) |

| Clinical pregnancy | ||||||

| White | 106,920 | 31,721 | 29.7 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Non-White | 51,893 | 13,749 | 26.5 | 0.89 (0.88–0.91) | 0.92 (0.90–0.93) | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) |

| Pregnancy loss | ||||||

| White | 106,920 | 3589 | 3.4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Non-White | 51,893 | 1885 | 3.6 | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) | 1.04 (0.97–1.13) |

| Live birth | ||||||

| White | 106,920 | 28,084 | 26.3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Non-White | 51,893 | 12,011 | 23.1 | 0.88 (0.86–0.90) | 0.91 (0.89–0.92) | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) |

| Total No. | No. Events | Rate Per 100 Cycles | Model 1 a | Model 2 b | Model 3 c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical pregnancy | ||||||

| White | 106,920 | 37,728 | 35.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 3781 | 1070 | 28.3 | 0.80 (0.76–0.84) | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) |

| Asian | 15,018 | 4871 | 32.4 | 0.60 (0.53–0.68) | 0.70 (0.64–0.78) | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) |

| Other | 33,094 | 10,533 | 31.8 | 0.47 (0.38–0.56) | 0.59 (0.51–0.69) | 0.89 (0.74–1.08) |

| Clinical pregnancy | ||||||

| White | 106,920 | 31,721 | 29.7 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 3781 | 906 | 24.0 | 0.81 (0.76–0.86) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | 0.97 (0.90–1.04) |

| Asian | 15,018 | 4006 | 26.7 | 0.60 (0.53–0.68) | 0.72 (0.64–0.80) | 0.94 (0.81–1.09) |

| Other | 33,094 | 8837 | 26.7 | 0.47 (0.38–0.56) | 0.61 (0.51–0.72) | 0.91 (0.73–1.14) |

| Pregnancy loss | ||||||

| White | 106,920 | 3270 | 3.1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 3781 | 124 | 3.3 | 1.07 (0.90–1.28) | 1.13 (0.96–1.34) | 1.14 (0.92–1.42) |

| Asian | 15,018 | 480 | 3.2 | 1.15 (0.81–1.64) | 1.29 (0.93–1.79) | 1.31 (0.84–2.03) |

| Other | 33,094 | 1079 | 3.3 | 1.23 (0.73–2.09) | 1.46 (0.89–2.39) | 1.49 (0.77–2.89) |

| Live birth | ||||||

| White | 106,920 | 28,084 | 26.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 3781 | 770 | 20.4 | 0.78 (0.73–0.83) | 0.82 (0.77–0.87) | 0.97 (0.90–1.05) |

| Asian | 15,018 | 3489 | 23.2 | 0.60 (0.53–0.68) | 0.67 (0.59–0.76) | 0.94 (0.80–1.11) |

| Other | 33,094 | 7752 | 23.4 | 0.47 (0.38–0.56) | 0.55 (0.46–0.66) | 0.92 (0.72–1.16) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, S.Q.; Dahan, M.H.; Lu, Y.; Cao, M.; Tan, J.; Tan, S.L. Partner Ethnicity and Assisted Reproductive Technology Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8962. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248962

Wei SQ, Dahan MH, Lu Y, Cao M, Tan J, Tan SL. Partner Ethnicity and Assisted Reproductive Technology Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8962. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248962

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Shu Qin, Michael H. Dahan, Yu Lu, Mingju Cao, Justin Tan, and Seang Lin Tan. 2025. "Partner Ethnicity and Assisted Reproductive Technology Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8962. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248962

APA StyleWei, S. Q., Dahan, M. H., Lu, Y., Cao, M., Tan, J., & Tan, S. L. (2025). Partner Ethnicity and Assisted Reproductive Technology Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8962. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248962