Comparative Analysis of Graft Survival in Older and Younger Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Single-Center Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Setting

2.2. Outcome Ascertainment

2.3. Follow-Up

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Differences Between Age Groups

3.3. Kidney Graft Failure

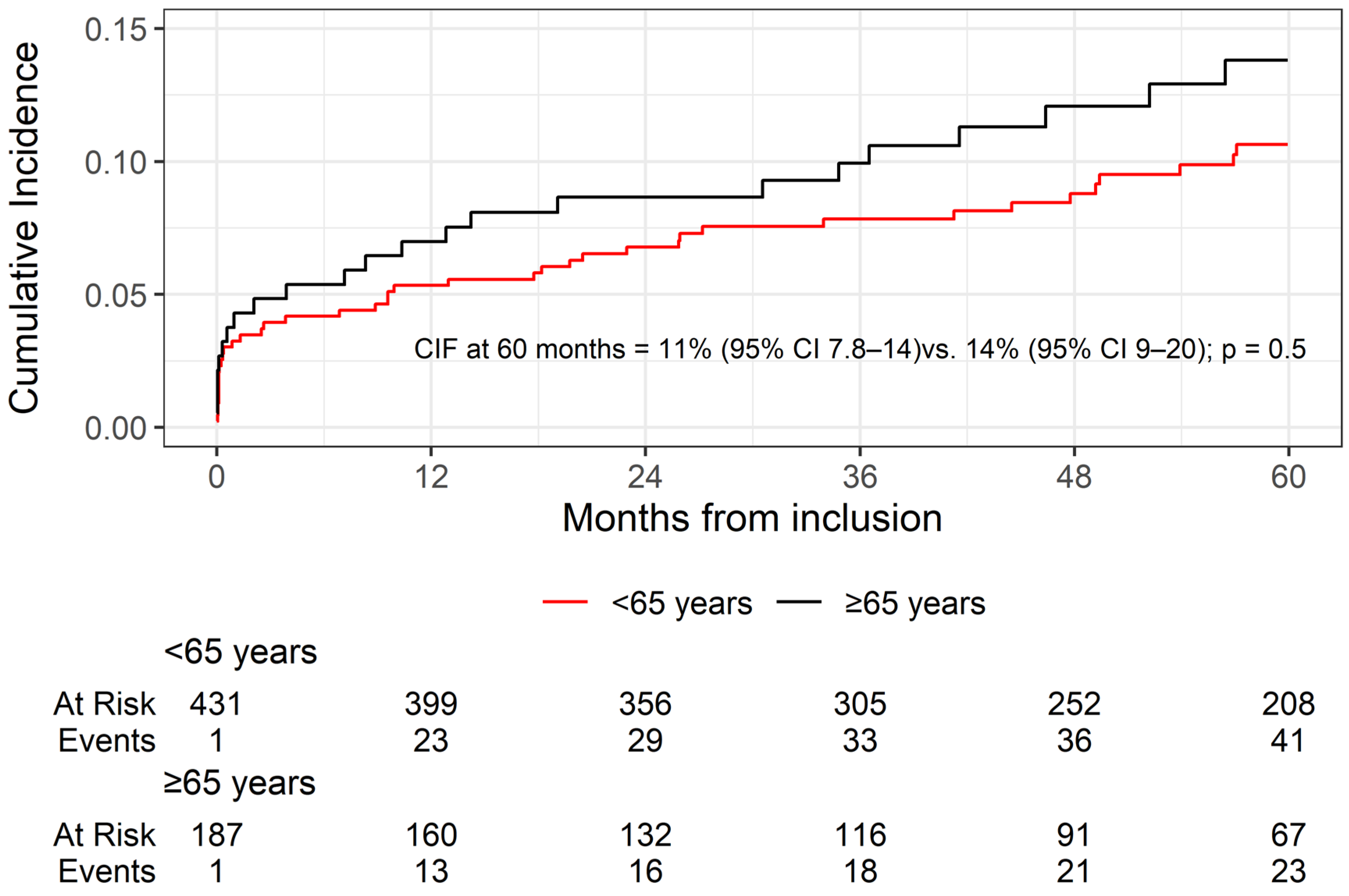

3.4. Overall Survival

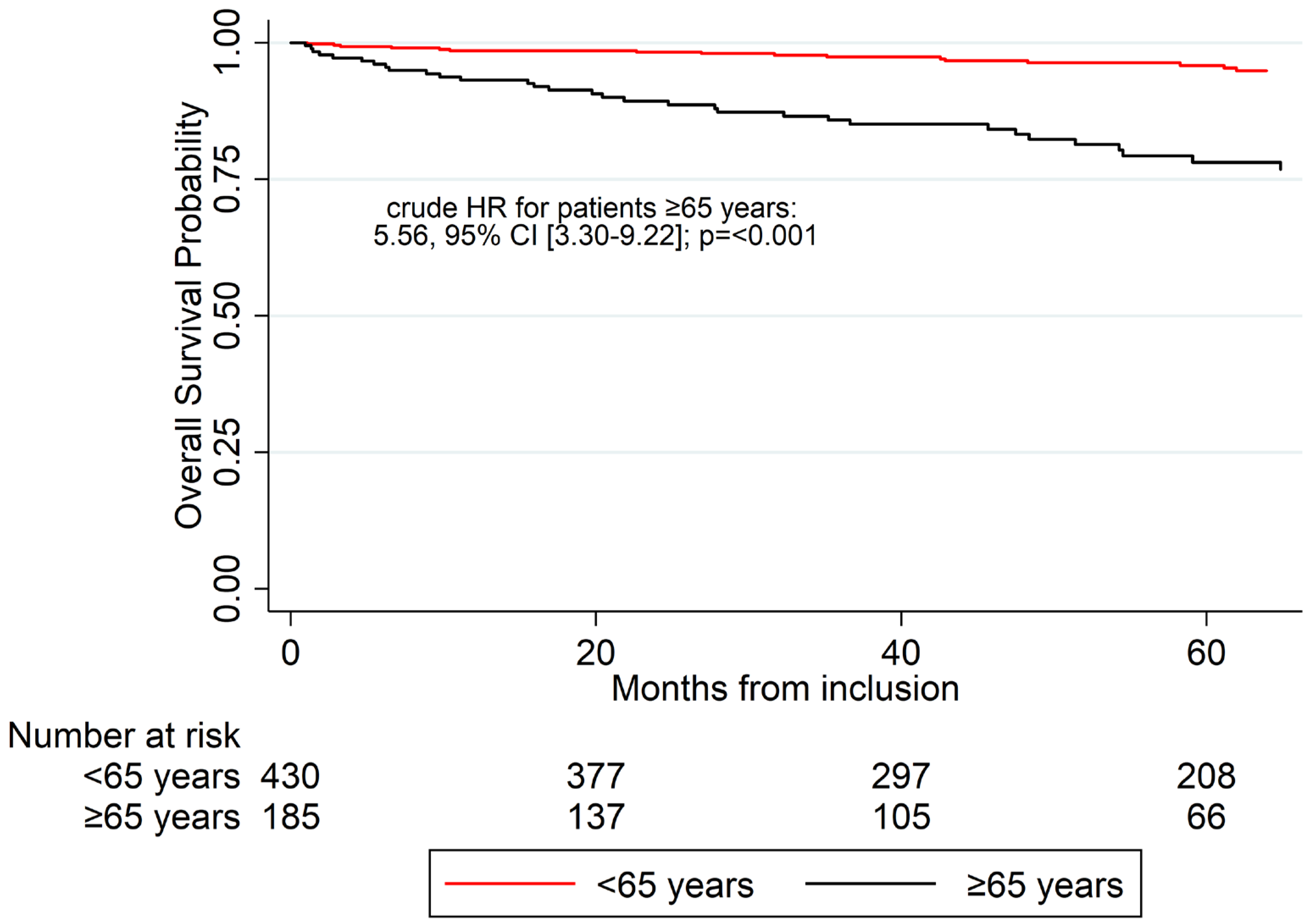

3.5. Multivariable Competing Risk Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Studies Showing Worse Graft Survival

4.2. Studies Showing Worse OS

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Implications and Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nations, U. Shifting Demographics. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/un75/shifting-demographics (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and the Global Public Health Agenda: An International Consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2024: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240094703 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Foreman, K.J.; Marquez, N.; Dolgert, A.; Fukutaki, K.; Fullman, N.; McGaughey, M.; Pletcher, M.A.; Smith, A.E.; Tang, K.; Yuan, C.-W.; et al. Forecasting Life Expectancy, Years of Life Lost, and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality for 250 Causes of Death: Reference and Alternative Scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 Countries and Territories. Lancet 2018, 392, 2052–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, N.R.; Fatoba, S.T.; Oke, J.L.; Hirst, J.A.; O’Callaghan, C.A.; Lasserson, D.S.; Hobbs, F.D.R. Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pippias, M.; Stel, V.S.; Abad Diez, J.M.; Afentakis, N.; Herrero-Calvo, J.A.; Arias, M.; Tomilina, N.; Bouzas Caamaño, E.; Buturovic-Ponikvar, J.; Čala, S.; et al. Renal Replacement Therapy in Europe: A Summary of the 2012 ERA-EDTA Registry Annual Report. Clin. Kidney J. 2015, 8, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyokabi, P.; Youngkong, S.; Bagepally, B.S.; Okech, T.; Chaikledkaew, U.; McKay, G.J.; Attia, J.; Thakkinstian, A. A Systematic Review and Quality Assessment of Economic Evaluations of Kidney Replacement Therapies in End-Stage Kidney Disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, D.; Chaudhry, A.; Peracha, J.; Sharif, A. Survival for Waitlisted Kidney Failure Patients Receiving Transplantation versus Remaining on Waiting List: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2022, 376, e068769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Ng, Y.-H.; Unruh, M. Kidney Transplantation Among the Elderly: Challenges and Opportunities to Improve Outcomes. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016, 23, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, A.; Domínguez, A.; Subiela, J.D.; Boissier, R.; Campi, R.; Prudhomme, T.; Pecoraro, A.; Breda, A.; Burgos, F.J.; Territo, A.; et al. Kidney Transplant Outcomes in Elderly Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2023, 51, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quint, E.E.; Pol, R.A.; Segev, D.L.; McAdams-DeMarco, M.A. Age Is Just a Number for Older Kidney Transplant Patients. Transplantation 2025, 109, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, D.J.; Gebregziabher, M.; Payne, E.H.; Srinivas, T.; Baliga, P.K.; Egede, L.E. Overall Graft Loss Versus Death-Censored Graft Loss: Unmasking the Magnitude of Racial Disparities in Outcomes Among US Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2017, 101, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coemans, M.; Verbeke, G.; Döhler, B.; Süsal, C.; Naesens, M. Bias by Censoring for Competing Events in Survival Analysis. BMJ 2022, 378, e071349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordzij, M.; Leffondré, K.; van Stralen, K.J.; Zoccali, C.; Dekker, F.W.; Jager, K.J. When Do We Need Competing Risks Methods for Survival Analysis in Nephrology? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 2670–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, F.; Friesen, E.L.; Clark, K.E.; Motaghi, S.; Zyla, R.; Lee, Y.; Kamran, R.; Ali, E.; De Snoo, M.; Orchanian-Cheff, A.; et al. Risk Factors for 1-Year Graft Loss After Kidney Transplantation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doucet, B.P.; Cho, Y.; Campbell, S.B.; Johnson, D.W.; Hawley, C.M.; Teixeira-Pinto, A.R.M.; Isbel, N.M. Kidney Transplant Outcomes in Elderly Recipients: An Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) Registry Study. Transpl. Proc. 2021, 53, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pletcher, J.; Koizumi, N.; Nayebpour, M.; Alam, Z.; Ortiz, J. Improved Outcomes after Live Donor Renal Transplantation for Septuagenarians. Clin. Transplant. 2020, 34, e13808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shraideh, Y.; Farooq, U.; Farney, A.C.; Palanisamy, A.; Rogers, J.; Orlando, G.; Buckley, M.R.; Reeves-Daniel, A.; Doares, W.; Kaczmorski, S.; et al. Influence of Recipient Age on Deceased Donor Kidney Transplant Outcomes in the Expanded Criteria Donor Era. Clin. Transplant. 2014, 28, 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, M.Z.; Streja, E.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Shah, A.; Huang, E.; Bunnapradist, S.; Krishnan, M.; Kopple, J.D.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Age and the Associations of Living Donor and Expanded Criteria Donor Kidneys with Kidney Transplant Outcomes. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2012, 59, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentine, K.L.; Smith, J.M.; Lyden, G.R.; Miller, J.M.; Dolan, T.G.; Bradbrook, K.; Larkin, L.; Temple, K.; Handarova, D.K.; Weiss, S.; et al. OPTN/SRTR 2022 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am. J. Transpl. 2024, 24, S19–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudhomme, T.; Bento, L.; Frontczak, A.; Timsit, M.-O.; Boissier, R. Effect of Recipient Body Mass Index on Kidney Transplantation Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by the Transplant Committee from the French Association of Urology. Eur. Urol. Focus 2024, 10, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravisani, R.; Isola, M.; Baccarani, U.; Crestale, S.; Tulissi, P.; Vallone, C.; Risaliti, A.; Cilloni, D.; Adani, G.L. Impact of Kidney Transplant Morbidity on Elderly Recipients’ Outcomes. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Churilla, B.; Ahn, J.B.; Quint, E.E.; Sandal, S.; Musunuru, A.; Pol, R.A.; Hladek, M.D.; Crews, D.C.; Segev, D.L.; et al. Age Disparities in Access to First and Repeat Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation 2024, 108, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hennawy, H.M.; Azeem, S.M.; Safar, O.; Al Faifi, A.S.; Al Atta, E.; El Madawie, M.Z.; El Gamal, G.A.; Azeem, S.; Tawhari, I.; Shalkamy, O. Clinical Outcomes of Living Donor Kidney Transplant in Older Recipients: A Retrospective Single-Center Analysis. Exp. Clin. Transpl. 2025, 23, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramitsu, T.; Tomosugi, T.; Futamura, K.; Okada, M.; Matsuoka, Y.; Goto, N.; Ichimori, T.; Narumi, S.; Takeda, A.; Kobayashi, T.; et al. Adult Living-Donor Kidney Transplantation, Donor Age, and Donor–Recipient Age. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 3026–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visan, S.R.; Baruch, R.; Schwartz, D.; Schwartz, I.F.; Goykhman, Y.; Raz, M.A.; Shashar, M.; Cohen-Hagai, K.; Nacasch, N.; Kliuk-Ben-Bassat, O.; et al. The Long-Term Outcome of Kidney Transplant Recipients in the Eighth Decade Compared With Recipients in the Seventh Decade of Life. Transpl. Proc. 2023, 55, 2063–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.P.-Y.; Patel, S.; Bradbrook, K.; Booker, S.; Ali, N.; Orandi, B.J.; Massie, A.B.; Segev, D.L.; Lonze, B.E.; Stewart, D.E. The Rapidly Shifting Calibration between Kidney Donor Risk Index, Kidney Donor Profile Index, and Graft Survival: Is It Time to Stop Moving the Goalposts? Am. J. Transplant. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; White, M.H.; Parker, W.F. Clinical Utility of KDPI Models After Race and HCV Removal: A Decision Curve Analysis. Am. J. Transplant. 2025, 25, S365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.B.; Bloom, R.D.; Reese, P.P.; Porrett, P.M.; Forde, K.A.; Sawinski, D.L. National Outcomes of Kidney Transplantation from Deceased Diabetic Donors. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsillo, A.; Kholmurodova, F.; Clayton, P.A.; Chadban, S.; Weightman, A.; Irish, G.L. The Impact of Donor and Recipient Diabetes on Patient and Graft Survival in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025, 10, 3834–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, J.S.; Song, S.H.; Song, S.H.; Shin, H.S.; Yang, J.; Ahn, C.; Jeong, K.H.; Hwang, H.S. Kotry Study Group Impact of Donor Hypertension on Graft Survival and Function in Living and Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation: A Nationwide Prospective Cohort Study. J. Hypertens. 2022, 40, 2200–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A.; Scott, D.; Stack, M.; de Mattos, A.; Norman, D.; Rehman, S.; Lockridge, J.; Woodland, D.; Kung, V.; Andeen, N.K. Long-Standing Donor Diabetes and Pathologic Findings Are Associated with Shorter Allograft Survival in Recipients of Kidney Transplants from Diabetic Donors. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Nian, Y.; Guo, L.; Song, W. Frailty and Prognosis of Patients with Kidney Transplantation: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2023, 24, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loon, I.N.; Wouters, T.R.; Boereboom, F.T.J.; Bots, M.L.; Verhaar, M.C.; Hamaker, M.E. The Relevance of Geriatric Impairments in Patients Starting Dialysis: A Systematic Review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, V.; Gross, A.L.; Chu, N.M.; Segev, D.; Hall, R.K.; McAdams-DeMarco, M. Domains for a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment of Older Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease: Results from the CRIC Study. Am. J. Nephrol. 2023, 53, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams-DeMarco, M.A.; Law, A.; Tan, J.; Delp, C.; King, E.A.; Orandi, B.; Salter, M.; Alachkar, N.; Desai, N.; Grams, M.; et al. Frailty, Mycophenolate Reduction, and Graft Loss in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2015, 99, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, V.P.; Idu, M.M.; Legemate, D.A.; Laguna Pes, M.P.; Minnee, R.C. Ureterovesical Anastomotic Techniques for Kidney Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transpl. Int. 2014, 27, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, S.V.; Krahn, M.D.; Naglie, G.; Zaltzman, J.S.; Roscoe, J.M.; Cole, E.H.; Redelmeier, D.A. Kidney Transplantation in the Elderly: A Decision Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 412 (67%) |

| Female | 206 (33%) |

| Recipient’s age, median (IQR) | 58 (47, 66) |

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 75 (65, 86.2) |

| Height (cm), median (IQR) | 166 (160, 173) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 27.2 (23.9–30.8) |

| Type of donor | |

| Donors after circulatory death | 120 (19%) |

| Donors after brain death | 498 (81%) |

| Donor’s sex | |

| Male | 374 (61%) |

| Female | 236 (38%) |

| Donor’s age, median (IQR) | 58 (48, 67) |

| Previous grafts | 82 (13%) |

| Hypertension | 533 (86%) |

| Diabetes | 177 (29%) |

| Number of grafts | |

| First | 536 (87%) |

| Second | 76 (12%) |

| Third | 6 (1%) |

| More than one kidney graft artery | 107 (17%) |

| More than one kidney graft vein | 10 (2%) |

| More than one kidney graft ureter | 6 (1%) |

| Ischemia time (hours), median (IQR) | 14 (7.5, 19) |

| Length of stay in days, median (IQR) | 11 (9, 16) |

| Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3 complications | 153 (25%) |

| Arterial stenosis | 13 (2%) |

| Thrombosis | 7 (1%) |

| Ureteral stenosis | 33 (5%) |

| Postoperative transfusion | 177 (29%) |

| Renal graft hematoma | 46 (7%) |

| Postoperative hematuria | 40 (6%) |

| BK virus infection | 40 (6%) |

| Symptomatic Lymphocele | 29 (5%) |

| Lithiasis | 3 (<1%) |

| Urine leaks | 19 (3%) |

| Wound complications | 42 (7%) |

| Variable | <65 Years | ≥65 Years | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | <70 Years | ≥70 Years | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 431 (70) | 187 (30) | 524 (83%) | 94 (15%) | |||||

| Female receptors, n (%) | 153 (35%) | 53 (28%) | 0.1 * | 0.72 (0.49–1.04) | 0.08 | 178 (34%) | 28 (30%) | 0.4 * |

| Recipient’s age, mean (SD) | 50.30 (10.06) | 70.12 (4.25) | <0.001 µ | 53.2 (11.09) | 73.49 (3.31) | <0.001 µ | ||

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 27.21 (4.79) | 28.02 (4.15) | 0.047 µ | 1.04 (1–1.08) | 0.047 | 27.25 (4.66) | 28.57 (4.29) | 0.01 µ |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 361 (84%) | 172 (92%) | 0.01 * | 2.22 (1.24–4) | 0.01 | 447 (85%) | 86 (91%) | 0.1 * |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 99 (23%) | 78 (42%) | <0.001 * | 2.4 (1.66–3.46) | <0.001 | 134 (26%) | 43 (46%) | <0.001 * |

| Previous grafts, n (%) | 60 (14%) | 22 (12%) | 0.5 * | 0.82 (0.49–1.39) | 0.5 | 75 (14%) | 7 (7%) | 0.1 * |

| Donor’s age, mean (SD) | 51.27 (13.64) | 66.72 (9.47) | <0.001 µ | 1.13 (1.11–1.16) | <0.001 | 53.69 (14.12) | 68.59 (7.86) | <0.001 µ |

| Female donors, n (%) | 166 (39%) | 70 (38%) | 0.8 * | 0.95 (0.67–1.35) | 0.8 | 202 (39%) | 34 (37%) | 0.6 * |

| Ischemia time (hours), mean (SD) | 13.40 (6.28) | 14.49 (6.76) | 0.04 µ | 1.03 (1–1.06) | 0.06 | 13.40 (6.28) | 14.49 (6.76) | 0.04 µ |

| Length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 13.16 (8.47) | 15.99 (11.76) | <0.001 µ | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | <0.001 | 13.68 (8.97) | 15.88 (12.73) | 0.04 µ |

| DCD, n (%) | 80 (19%) | 40 (21%) | 0.4 * | 0.84 (0.55–1.28) | 0.4 | 96 (18%) | 24 (26%) | 0.1 * |

| More than one artery, n (%) | 74 (17%) | 33 (18%) | 0.9 * | 1.03 (0.66–1.62) | 0.9 | 93 (18%) | 14 (15%) | 0.5 * |

| More than one vein, n (%) | 7 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 0.6 θ | 0.99 (0.25–3.86) | 0.99 | 8 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 0.5 θ |

| More than one ureter, n (%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 0.3 θ | 2.33 (0.47–11.63) | 0.3 | 5 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0.6 θ |

| Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3 complications, n (%) | 91 (21%) | 62 (33%) | 0.001 * | 1.85 (1.26–2.72) | <0.001 | 122 (23%) | 31 (33%) | 0.045 * |

| 60-Month Overall Survival | 60-Month Kidney Graft Failure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Crude Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value * | Crude Subhazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value µ |

| ≥65 years | 5.56 (3.35–9.22) | <0.001 | 1.15 (0.73–1.80) | 0.5 |

| Female receptors | 0.73 (0.43–1.25) | 0.4 | 0.98 (0.63–1.51) | 0.9 |

| Body mass index | 1.06 (1.00–1.11) | 0.03 | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 0.1 |

| Hypertension | 2.16 (0.87–5.38) | 0.7 | 1.11 (0.59–2.09) | 0.7 |

| Diabetes | 2.22 (1.36–3.61) | 0.001 | 1.36 (0.87–2.12) | 0.2 |

| Previous grafts | 1.11 (0.55–2.25) | 0.8 | 1.06 (0.55–2.01) | 0.9 |

| Donor’s age | 1.06 (1.03–1.08) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 |

| Female donors | 1.14 (0.69–1.87) | 0.6 | 1.61 (1.05–2.48) | 0.03 |

| Ischemia time (hours) | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.5 | 1.02 (0.98–1.05) | 0.3 |

| Length of stay (days) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | <0.001 |

| Donors After Circulatory Death | 0.36 (0.20–0.63) | <0.001 | 1.36 (0.70–2.65) | 0.4 |

| More than one artery | 1.16 (0.62–2.17) | 0.6 | 0.81 (0.44–1.49) | 0.5 |

| More than one vein | 3.47 (0.84–14.30) | 0.1 | 2.01 (0.46–8.78) | 0.4 |

| More than one ureter | 1.13 (0.16–8.16) | 0.9 | 1.87 (0.57–6.16) | 0.3 |

| Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3 complications | 2.16 (1.13–3.56) | 0.003 | 2.30 (1.49–3.45) | <0.001 |

| ≥65 Years Threshold | ≥70 Years Threshold | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted Subhazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value µ | Adjusted Subhazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value µ |

| Older patients | 0.73 (0.41–1.29) | 0.3 | 0.79 (0.40–1.55) | 0.5 |

| Female receptors | 1.06 (0.67–1.67) | 0.8 | 1.05 (0.67–1.66) | 0.8 |

| Body mass index | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | 0.2 | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | 0.2 |

| Hypertension | 1.17 (0.57–2.41) | 0.7 | 1.17 (0.56–2.47) | 0.7 |

| Diabetes | 1.07 (0.60–1.89) | 0.8 | 1.04 (0.59–1.81) | 0.9 |

| Previous grafts | - | - | 0.92 (0.42–2.01) | 0.8 |

| Donor’s age | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.04 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.1 |

| Female donors | 1.72 (1.09–2.73) | 0.02 | 1.75 (1.10–2.78) | 0.02 |

| Ischemia time (hours) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.9 | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.9 |

| Length of stay (days) | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.04 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.04 |

| Donors After Circulatory Death | 1.28 (0.64–2.58) | 0.5 | 1.27 (0.63–2.58) | 0.3 |

| More than one vein | 2.49 (0.49–12.55) | 0.5 | 2.51 (0.49–12.97) | 0.3 |

| Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3 complications | 1.57 (0.90–2.73) | 0.1 | 1.56 (0.89–2.72) | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González Serrano, A.; Guldris García, R.J.; Gómez Marqués, G.; Ruiz Hernández, M.; Pieras Ayala, E.C. Comparative Analysis of Graft Survival in Older and Younger Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Single-Center Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8953. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248953

González Serrano A, Guldris García RJ, Gómez Marqués G, Ruiz Hernández M, Pieras Ayala EC. Comparative Analysis of Graft Survival in Older and Younger Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Single-Center Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8953. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248953

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález Serrano, Adolfo, Ricardo José Guldris García, Gonzalo Gómez Marqués, Mercedes Ruiz Hernández, and Enrique Carmelo Pieras Ayala. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of Graft Survival in Older and Younger Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Single-Center Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8953. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248953

APA StyleGonzález Serrano, A., Guldris García, R. J., Gómez Marqués, G., Ruiz Hernández, M., & Pieras Ayala, E. C. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Graft Survival in Older and Younger Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Single-Center Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8953. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248953