Impact of Endodontic Treatment on CRP Levels in Apical Periodontitis: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling and Patient Selection

2.2. Blood Collection

2.3. Blinding Considerations

2.4. Root Canal Treatment or Retreatment

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Reduction in CRP Levels After Endodontic Treatment

3.3. Comparison Between SAP and AAP

3.4. Influence of Age and Sex

3.5. Sensitivity Analyses

Clinical Relevance

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kakehashi, S.; Stanley, H.R.; Fitzgerald, R.J. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1965, 20, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, P.N. Pathogenesis of apical periodontitis and the causes of endodontic failures. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2004, 15, 348–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, P.V. Classification, diagnosis and clinical manifestations of apical periodontitis. Endod. Top. 2004, 8, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibúrcio-Machado, C.S.; Michelon, C.; Zanatta, F.B.; Gomes, M.S.; Marin, J.A.; Bier, C.A. The global prevalence of apical periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 712–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiyaveetil Karattil, L.; Joseph, R.S.; Ambooken, M.; Mathew, J.J. Evaluation of serum concentrations of hs-CRP and Hb in varying severities of chronic periodontitis. Biomark. Biochem. Indic. Expo. Response Susceptibility Chem. 2022, 27, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.F.; Malmstrom, H.S. Rapid quantitative determination of C-reactive protein at chair side in dental emergency patients. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2007, 104, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakimiak, A.; Kochańska, M.; Michalska, M.; Celej, M.; Wojtowicz, A.; Popowski, W. Serum concentration of C-reactive protein in patients treated for acute and chronic odontogenic infections. Med. Probl. 2016, 53, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Bhardwaj, M.; Doley, B.; Manas, A.; Ismail, P.M.S.; Patil, P.B.; Singh, K.K. Expression of IL-6, TNF-alpha, and hs-CRP in the serum of patients undergoing single-sitting and multiple-sitting root canal treatment: A comparative study. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 1918–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Losada, F.L.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; Castellanos-Cosano, L.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Lopez-Lopez, J.; Velasco-Ortega, E. Apical periodontitis and diabetes mellitus type 2: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş, E.; Kul, A.; Tepecik, E. Association between rheumatoid arthritis and apical periodontitis: A cross-sectional study. Eur. Endod. J. 2020, 5, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Rotstein, I. Prevalence of periapical lesions in patients with osteoporosis. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piras, V.; Usai, P.; Mezzena, S.; Susnik, M.; Ideo, F.; Schirru, E.; Cotti, E. Prevalence of apical periodontitis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: A retrospective clinical study. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, J.; Glassl, E.M.; Nasseri, P.; Crismani, A.; Luger, A.K.; Schoenherr, E.; Bertl, K.; Glodny, B. The association of chronic apical periodontitis and endodontic therapy with atherosclerosis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 18, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zahrani, M.S.; Abozor, B.M.; Zawawi, K.H. The relationship between periapical lesions and the serum levels of glycosylated hemoglobin and C-reactive protein in type 2 diabetic patients. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poornima, L.; Ravishankar, P.; Abbott, P.; Subbiya, A.; PradeepKumar, A. Impact of root canal treatment on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels in systemically healthy adults with apical periodontitis–a preliminary prospective, longitudinal interventional study. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, A.; Moyes, D.; Proctor, G.; Mannocci, F.; Niazi, S.A. The impact of apical periodontitis, non-surgical root canal retreatment and periapical surgery on serum inflammatory biomarkers. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdulla, N.; Bakhsh, A.; Mannocci, F.; Proctor, G.; Moyes, D.; Niazi, S.A. Successful endodontic treatment reduces serum levels of cardiovascular disease risk biomarkers—High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, asymmetric dimethylarginine, and matrix metalloprotease-2. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 1499–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazmi, A.; Victora, C.G. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic differentials of C-reactive protein levels: A systematic review of population-based studies. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.R.; Leahy, I.; Staffa, S.J.; Johnson, C.; Crofton, C.; Methot, C.; Berry, J.G. One size does not fit all: A perspective on the American society of anesthesiologists physical status classification for pediatric patients. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 130, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, D.; Aghanashini, S.; Vijayendra, R.R.; Chatterjee, A.; Rosh, R.M.; Bharwani, A. Effect of periodontal therapy on C-reactive protein levels in gingival crevicular fluid of patients with gingivitis and chronic periodontitis: A clinical and biochemical study. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2014, 18, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, S.K.; Banerjee, D.; Wang, C.; Nag, S. Evaluation of Microflora and Its Antibiotic Susceptibility from Failed Endodontic Cases (an In-Vivo Study). Int. J. Acad. Med. Pharm. 2025, 7, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, T.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Alexander, R.W.; Anderson, J.L.; Cannon, R.O., III; Criqui, M.; Fadl, Y.Y.; Fortmann, S.P.; Hong, Y.; Myers, G.L. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: Application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2003, 107, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghofaily, M.; Tordik, P.; Romberg, E.; Martinho, F.; Fouad, A.F. Healing of apical periodontitis after nonsurgical root canal treatment: The role of statin intake. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visser, M.; Bouter, L.M.; McQuillan, G.M.; Wener, M.H.; Harris, T.B. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. Jama 1999, 282, 2131–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElAyouti, A.; Dima, E.; Ohmer, J.; Sperl, K.; von Ohle, C.; Löst, C. Consistency of apex locator function: A clinical study. J. Endod. 2009, 35, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, Z.; Al-Jadaa, A.; Saleh, A.R. Electronic apex locators and their implications in contemporary clinical practice: A review. Open Dent. J. 2023, 17, e187421062212270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehnder, M. Root canal irrigants. J. Endod. 2006, 32, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.P.; Vianna, M.E.; Zaia, A.A.; Almeida, J.F.A.; Souza-Filho, F.J.; Ferraz, C.C. Chlorhexidine in endodontics. Braz. Dent. J. 2013, 24, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, H.; Petronijevic, N.; Mdala, I.; Kristoffersen, A.K.; Enersen, M.; Rôças, I.N.; Siqueira, J.F., Jr.; Ørstavik, D. Outcome of endodontic retreatment using 2 root canal irrigants and influence of infection on healing as determined by a molecular method: A randomized clinical trial. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 1089–1098.e1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roi, C.I.; Roi, A.; Nicoară, A.; Nica, D.; Rusu, L.C.; Soancă, A.; Motofelea, A.C.; Riviș, M. Impact of treatment on systemic immune-inflammatory index and other inflammatory markers in odontogenic cervicofacial phlegmon cases: A retrospective study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Kumari, M. Age modification of the relationship between C-reactive protein and fatigue: Findings from Understanding Society (UKHLS). Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, A.; McGuire, D.K.; Murphy, S.A.; Stanek, H.G.; Das, S.R.; Vongpatanasin, W.; Wians, F.H.; Grundy, S.M.; de Lemos, J.A. Race and gender differences in C-reactive protein levels. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 46, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ward, J.; Strawbridge, R.J.; Celis-Morales, C.; Pell, J.P.; Lyall, D.M.; Ho, F.K. How do lifestyle factors modify the association between genetic predisposition and obesity-related phenotypes? A 4-way decomposition analysis using UK Biobank. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Criteria |

|---|---|

| The Inclusion Criteria | ASA I patients: ASA I refers to patients classified by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System as healthy individuals with no systemic disease, non-smokers, minimal alcohol use, and normal BMI [19]. |

| Presence of apical periodontitis (symptomatic or asymptomatic) diagnosed per AAE guidelines | |

| One tooth requiring endodontic treatment or retreatment with pulpal diagnoses: symptomatic/asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis, pulp necrosis, or previously treated. The inclusion of these pulpal diagnoses was necessary because the primary focus of this study was on the condition of the periapical tissues (symptomatic or asymptomatic apical periodontitis), not the pulpal status. This approach ensured that all cases had apical involvement regardless of pulp condition | |

| Clearance of periodontal and gingival inflammation by a general dentist: This criterion was included to eliminate the potential confounding effects of periodontal disease on CRP levels, as periodontal inflammation is known to significantly influence systemic inflammatory markers [20]. | |

| The Exclusion Criteria | Patients with systemic disease |

| Normal periapical region (radiographically intact periapical tissues), referring to radiographically intact periapical tissues without any signs of radiolucency, as assessed according to AAE guidelines. | |

| Recent hospitalization within the past 24 months | |

| Moderate or severe marginal periodontal disease | |

| Antibiotic or corticosteroid use within the previous 3 months: The three-month exclusion period was chosen to minimize residual systemic effects of antibiotics and corticosteroids on inflammatory markers such as CRP. Evidence indicates that CRP levels typically normalize within 6–8 weeks after cessation of anti-inflammatory or antimicrobial therapy, and some studies recommend a conservative window of up to three months to ensure complete washout [21,22]. | |

| Medications affecting bone metabolism (e.g., bisphosphonates, SSRIs, HRT) | |

| Smokers | |

| Pregnant women | |

| Obesity | |

| Refusal to provide blood samples | |

| Inability to attend follow-up appointments |

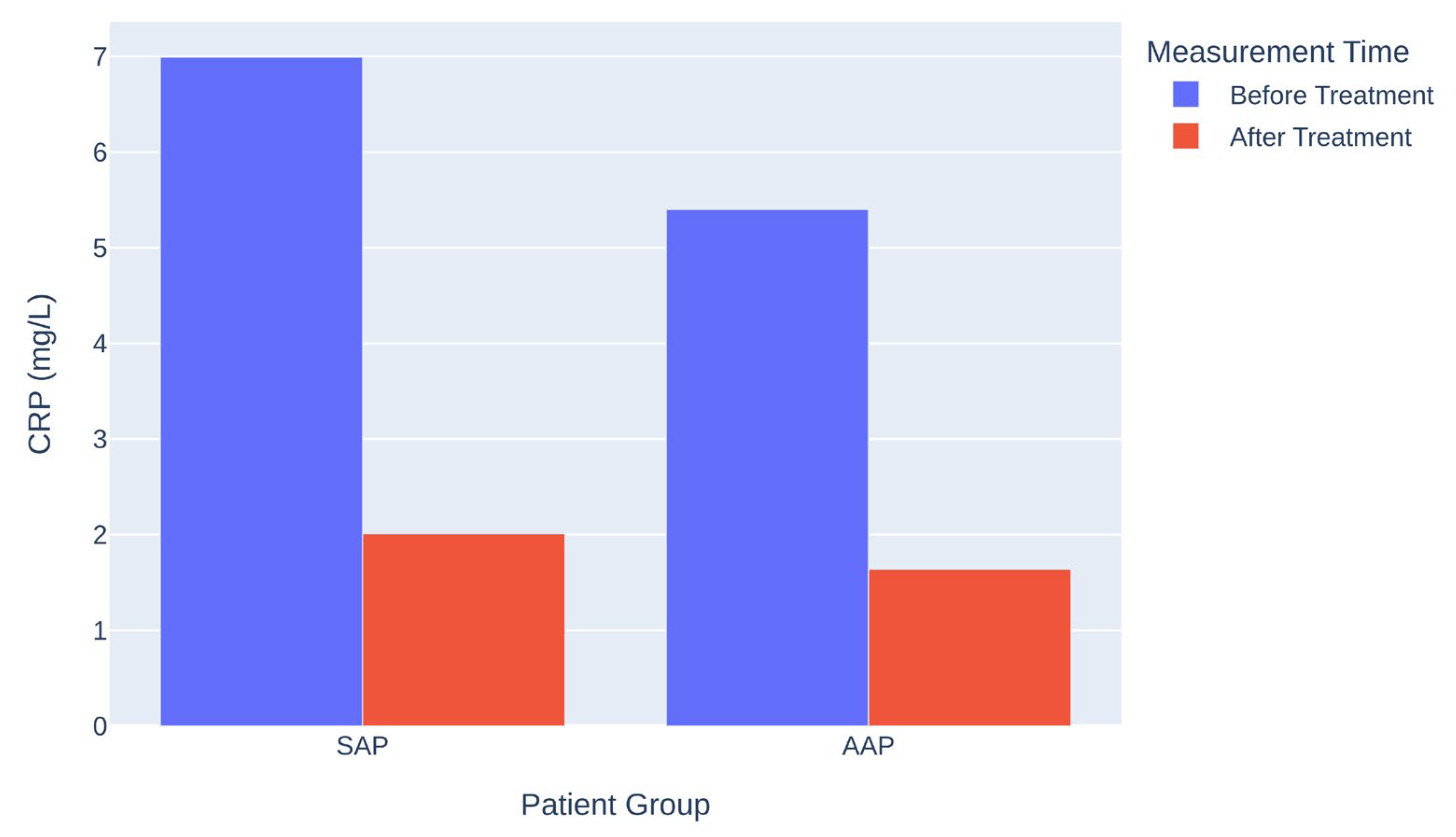

| Group | CRP Before (mg/L) | CRP After (mg/L) | Mean Difference (mg/L) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAP | 6.99 | 2.01 | 4.98 | <0.001 |

| AAP | 5.40 | 1.64 | 3.76 | <0.001 |

| Variable | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Age | >0.05 | Not a significant predictor |

| Sex | >0.05 | Not a significant predictor |

| Group | PAI Score (Mean ± SD) | N | Std Error Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAP | 2.67 ± 1.040 | 78 | 0.118 |

| SAP | 2.78 ± 1.033 | 222 | 0.068 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al akam, H.; Abduljawad, A.A.; Abozor, B. Impact of Endodontic Treatment on CRP Levels in Apical Periodontitis: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8929. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248929

Al akam H, Abduljawad AA, Abozor B. Impact of Endodontic Treatment on CRP Levels in Apical Periodontitis: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8929. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248929

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl akam, Hussain, Asaad Abdulrahman Abduljawad, and Basel Abozor. 2025. "Impact of Endodontic Treatment on CRP Levels in Apical Periodontitis: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8929. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248929

APA StyleAl akam, H., Abduljawad, A. A., & Abozor, B. (2025). Impact of Endodontic Treatment on CRP Levels in Apical Periodontitis: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8929. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248929