Quality of Life in Long-Standing Rheumatoid Arthritis: What Can Help Apart from Treatment? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Sample

2.2.1. Sample Size Considerations

2.2.2. Procedures

2.2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Statistical Analysis

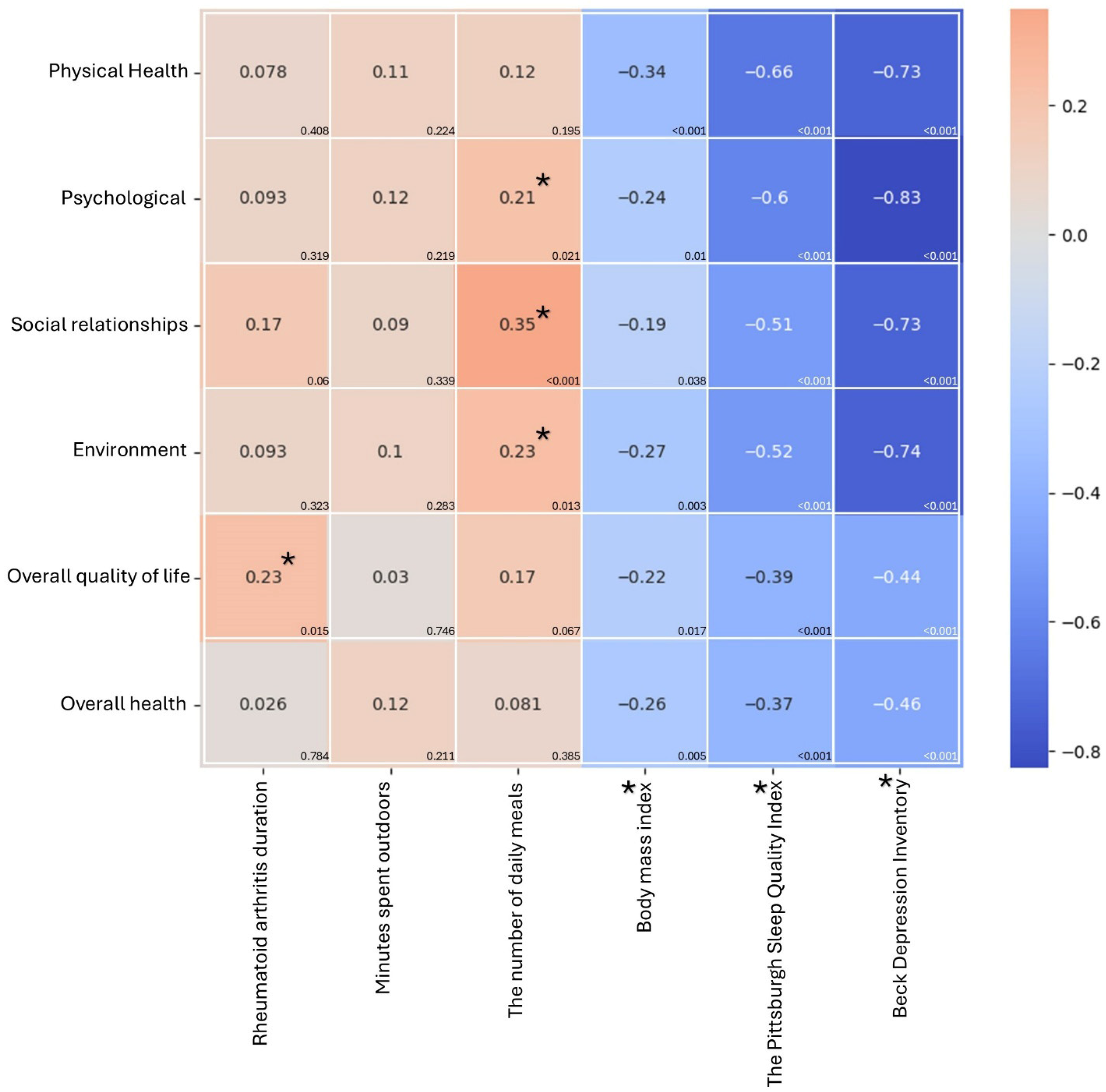

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. WHOQOL-BREF Questionnaire Scoring

3.3. Differences in Demographic Characteristics and WHOQOL-BREF Questionnaire Scoring

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| IQR | reported as median |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| WHOQOL-BREF | World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument, Short Form |

References

- Safiri, S.; Kolahi, A.A.; Hoy, D.; Smith, E.; Bettampadi, D.; Mansournia, M.A.; Almasi-Hashiani, A.; Ashrafi-Asgarabad, A.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; Qorbani, M.; et al. Global, regional and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis 1990–2017: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2017. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; Inoue, E.; Shimizu, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Shidara, K.; Sugimoto, N.; Seto, Y.; Tanaka, E.; Taniguchi, A.; Momohara, S.; et al. Presence of comorbidity affects both treatment strategies and outcomes in disease activity, physical function, and quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015, 34, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka-Skurska, I.; Sierakowska, M.; Kułak, W. Evaluation of quality of life in chronic, progressing rheumatic diseases based on the example of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.F.R.; Duarte, C.; Ferreira, R.J.O.; Santos, E.; da Silva, J.A.P. Depression, disability and sleep disturbance are the main explanatory factors of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A path analysis model. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2020, 38, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, S.; Bode, C.; Taal, E.; van de Laar, M.A. Fatigue and factors related to fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 1128–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, M.R.; Systrom, D.M.; Rose, N.R. Fatigue, sleep, and autoimmune and related disorders. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Gonçalves, D.; Bernardes, M.; Costa, L. Quality of life and functional capacity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis—Cross-sectional study. Reumatol. Clin. (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 14, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, J.E. Management of Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis. RMD Open. 2020, 6, e001084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.M.; Lai, M.S.; Lin, H.Y.; Lang, H.C.; Lee, L.J.; Wang, J.D. Disease activity affects all domains of quality of life in patients with rheumatoid ar-thritis and is modified by disease duration. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2014, 32, 898–903, Erratum in Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2015, 33, 135.. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ausi, Y.; Sinuraya, R.K.; Dewi, S.; Barliana, M.I.; Postma, M.J.; Suwantika, A.A. Health-related quality of life and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study in West Java, Indonesia. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1682924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Becker, J.C.; Teng, J.; Dougados, M.; Schiff, M.; Smolen, J.; Aletaha, D.; van Riel, P.L. Validation of the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and European League Against Rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletaha, D.; Neogi, T.; Silman, A.J.; Funovits, J.; Felson, D.T.; Bingham, C.O., 3rd; Birnbaum, N.S.; Burmester, G.R.; Bykerk, V.P.; Cohen, M.D.; et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 2569–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, H.A.; Brooks, R.H.; Callahan, L.F.; Pincus, T. A simplified twenty-eight-joint quantitative articular index in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989, 32, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHOQOL-BREF_Syntax_Files. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref/docs/default-source/publishing-policies/whoqol-bref/polish_whoqol-bref71589543-d0e3-40cd-8e0a-cd171454a339; https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref/docs/default-source/publishing-policies/spss-syntax/whoqol-bref-syntax-files (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction Administration Scoring Generic Version of the Assessment: Field Trial Version December 1996. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHOQOL-BREF (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treatment Headache Diagnosis Brain Institute, O.H.S.U. Available online: https://www.ohsu.edu/brain-institute/headache-diagnosis-and-treatment (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khani, A.M.; Sarhandi, M.I.; Zaghloul, M.S.; Ewid, M.; Saquib, N. A cross-sectional survey on sleep quality, mental health, and academic performance among medical students in Saudi Arabia. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matcham, F.; Scott, I.C.; Rayner, L.; Hotopf, M.; Kingsley, G.H.; Norton, S.; Scott, D.L.; Steer, S. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2014, 44, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiphorou, E.; Norton, S.; Young, A.; Dixey, J.; Walsh, D.; Helliwell, H.; Kiely, P. Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study and the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Network. The association of obesity with disease activity, functional ability and quality of life in early rheumatoid arthritis: Data from the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study/Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Network UK prospective cohorts. Rheumatology 2018, 57, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle Grave, R.; Soave, F.; Ruocco, A.; Dametti, L.; Calugi, S. Quality of life and physical performance in patients with obesity: A network analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tański, W.; Świątoniowska-Lonc, N.; Tomasiewicz, A.; Dudek, K.; Jankowska-Polańska, B. The impact of sleep disorders on the daily activity and quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis patients–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 3212–3229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Kumar, V. Sleep quality is poor in rheumatoid arthritis patients and correlates with anxiety, Depression, and poor quality of life. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2024, 35, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetsanopoulou, A.I.; Alamanos, Y.; Voulgari, P.V.; Drosos, A.A. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Rheumatoid Arthritis Development. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2023, 34, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsing, C.L.; Igland, J.; Nystad, T.W.; Gjesdal, C.G.; Næss, H.; Tell, G.S.; Fevang, B.T. Trends in stroke occurrence in rheumatoid arthritis: A retrospective cohort study from Western Norway, 1972 through 2020. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1547518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woude, D.; van der Helm-van, A.H. Update on the epidemiology, risk factors, and disease outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 32, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, O.; Cavusoglu, C.; Satis, H.; Salman, R.B.; Varan, O.; Atas, N.; Coteli, S.; Dogrul, R.T.; Babaoglu, H.; Oncul, A.; et al. Sleep quality and its associations with disease activity and quality of life in older patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2023, 14, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; Yano, K.; Ikari, K.; Otani, N.; Hiroshima, R.; Okazaki, K. Cognitive Functional Impairment Associated With Physical Function and Frailty in Older Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2025, 28, e70181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, R.; Sano, C. Factors affecting the duration of initial medical care seeking among older rural patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Rheumatol. 2024, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstappen, S.M.M. The impact of socio-economic status in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2017, 56, 1051–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.H.; Huang, J.Y.; Chiou, J.Y.; Wei, J.C. Analysis of Socioeconomic Status in the Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J. Marital biography and health at mid-life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, T.F.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. The physiology of marriage: Pathways to health. Physiol Behav. 2003, 79, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Gao, W.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhou, J.; Zang, Y. Anxiety and depression in rheumatoid arthritis patients: Prevalence, risk factors and consistency between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Zung’s Self-rating Anxiety Scale/Depression Scale. Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 2023, 7, rkad100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, J.B.; Somers, T.J.; Keefe, F.J.; Mosley-Williams, A.; Lumley, M.A. Pain and functioning of rheumatoid arthritis patients based on marital status: Is a distressed marriage preferable to no marriage? J. Pain 2010, 11, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyberg, I.; Dahlstrom, O.; Bjork, M.; Arvidsson, P.; Thyberg, M. Potential of the HAQ score as clinical indicator suggesting comprehensive multidisciplinary assessments: The Swedish TIRA cohort 8 years after diagnosis of RA. Clin. Rheumatol. 2012, 31, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malm, K.; Bergman, S.; Andersson, M.; Bremander, A. Predictors of severe self-reported disability in RA in a long-term follow-up study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurkmans, E.; van der Giesen, F.J.; Vliet Vlieland, T.P.; Schoones, J.; Van den Ende, E.C. Dynamic exercise programs (aerobic capacity and/or muscle strength training) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2009, CD006853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsios, G.S.; Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou, A.; Veldhuijzen van Zanten, J.J.; Treharne, G.J.; Panoulas, V.F.; Douglas, K.M.; Koutedakis, Y.; Kitas, G.D. Rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease and physical exercise: A systematic review. Rheumatology 2008, 47, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rongen-van Dartel, S.A.; Repping-Wuts, H.; Flendrie, M.; Bleijenberg, G.; Metsios, G.S.; van den Hout, W.B.; van den Ende, C.H.; Neuberger, G.; Reid, A.; van Riel, P.L.; et al. Effect of Aerobic Exercise Training on Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015, 67, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokka, T.; Häkkinen, A. Poor physical fitness and performance as predictors of mortality in normal populations and patients with rheumatic and other diseases. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2008, 26, S14–S20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, M.H.; de Boer, I.G.; le Cessie, S.; Breedveld, F.C.; Vlieland, T.P.V. Most people with rheumatoid arthritis undertake leisure-time physical activity in the Netherlands: An observational study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2007, 53, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, J.N.; Zahavi, E.R.; Gorman, A.E.; Murray, K.; Turk, M.A.; Veale, D.J. Exploring the effect of alcohol on disease activity and outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis through systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H.; Vincent, A.; Clauw, D.J.; Luedtke, C.A.; Thompson, J.M.; Schneekloth, T.D.; Oh, T.H. Association between alcohol consumption and symptom severity and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013, 15, R42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, S.; Symeonidou, S.; Andersson, M.L.; Soderlin, M.K. Alcohol consumption is associated with lower self-reported disease activity and better health-related quality of life in female rheumatoid arthritis patients in Sweden: Data from BARFOT, a multicenter study on early RA. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, N.; Dey, M.; Norton, S.; Adas, M.; Bosworth, A.; Buch, M.H.; Cope, A.; Lempp, H.; Galloway, J.; Nikiphorou, E. Understanding the psychosocial determinants of effective disease management in rheumatoid arthritis to prevent persistently active disease: A qualitative study. RMD Open. 2024, 10, e004104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimer, P.; Stamp, L.; Stebbings, S.; Valentino, N.; Cameron, V.; Treharne, G.J. Identifying barriers to smoking cessation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015, 67, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malm, K.; Bremander, A.; Arvidsson, B.; Andersson, M.L.; Bergman, S.; Larsson, I. The influence of lifestyle habits on quality of life in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis-A constant balancing between ideality and reality. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2016, 11, 30534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlson, E.W.; Deane, K. Environmental and gene-environment interactions and risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2012, 38, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, A.; Yasin, S.; Ul Haq, Z.; Ahmad, I.; Hussain, M.; Pervez, N. Frequency of Sleep Disorders in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Cureus 2024, 16, e72417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, L.; Matcham, F.; Hutton, J.; Stringer, C.; Dobson, J.; Steer, S.; Hotopf, M. Embedding integrated mental health assessment and management in general hospital settings: Feasibility, acceptability and the prevalence of common mental disorder. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2014, 36, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, I.A.; Patten, S.B.; Barnabe, C. Depression and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2019, 31, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waraich, P.; Goldner, E.M.; Somers, J.M.; Hsu, L. Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Can. J. Psychiatry 2004, 49, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo-Braga, M.; Cornaby, C.; Cortez, A.; Bernardes, M.; Terroso, G.; Figueiredo, M.; Mesquita, C.D.S.; Costa, L.; Poole, B.D. Influence of Biological Therapeutics, Cytokines, and Disease Activity on Depression in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 5954897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygiel-Górniak, B.; Puszczewicz, M. Fatigue and interleukin-6—A multi-faceted relationship. Reumatologia 2015, 53, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlindungan, F.; Hidayat, R.; Ariane, A.; Shatri, H. Association between Proinflammatory Cytokines and Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Cross-sectional Study. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2023, 19, e174501792304261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group Characteristics of Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients (n = 116) | |

|---|---|

| Analyzed parameter | IQR; n (%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 89 (76.7) |

| Male | 27 (23.3) |

| Age | |

| Below 40 | 25 (21.6) |

| 41–60 | 59 (50.9) |

| Over 60 | 32 (27.6) |

| Place of residence | |

| Village | 40 (34.5) |

| City with up to 50 thousand inhabitants | 30 (25.9) |

| City with up to 100 thousand inhabitants | 20 (17.2) |

| A city with over 100 thousand inhabitants | 26 (22.4) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 21 (18.1) |

| married | 69 (59.5) |

| In a separation/divorce | 10 (8.6) |

| widower | 16 (13.8) |

| Physically active | |

| Smaller than the previous year | 82 (70.7) |

| Bigger than the previous year | 34 (29.3) |

| Minutes spent outdoors | 120 (90–180) |

| Meals per day | 4 (3–5) |

| Body mass index | 26 (22.7–30.2) |

| RA onset | 2006 (2000–2011) |

| DAS28-ESR | 2.65 (0.26) |

| Smoking | |

| Yes | 26 (22.4) |

| No | 90 (77.6) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Everyday | 1 (0.9) |

| Once a week | 12 (10.3) |

| Once a month | 9 (7.8) |

| Occasionally | 53 (45.7) |

| I don’t drink alcohol | 41 (35.3) |

| WHOQOL-BREF | |

| Physical Health | 50 (39.3–60.7) |

| Psychological | 66.7 (54.2–79.2) |

| Social Relationships | 75 (58.3–83.3) |

| Environment | 68.8 (56.3–78.1) |

| Overall QoL | 75 (50–75) |

| Overall health | 50 (25–75) |

| PSQI | |

| Good sleep | 28 (24.1) |

| Bad sleep | 88 (75.9) |

| BDI depression | |

| Extreme depression | 1(0.9) |

| Severe depression | 5 (4.3) |

| Moderate depression | 17 (14.7) |

| Borderline clinical depression | 14 (12.1) |

| Mild mood disturbances | 23 (19.8) |

| Normal | 56 (48.3) |

| Treatment line | |

| 1st | 2 (1.7) |

| 2nd | 36 (31) |

| 3rd | 57 (49.1) |

| 4th | 11 (9.5) |

| 5th | 9 (7.8) |

| 6th | 1 (0.9) |

| Physical Health | Psychological | Social Relationships | Environment | Overall QoL | Overall Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| Below 40 | 57.1 ± 13.7 b | 75 (66.7–83.3) b | 83.3 (66.7–91.7) b | 72 ± 13.4b | 75 (50–75) b | 75 (50–75) b |

| 41–60 | 47.5 ± 13.4 a | 66.7 (54.2–79.2) a,b | 75 (58.3–75) a | 65.6 ± 14.3 a,b | 75 (50–75) b | 50 (25–75) a,b |

| Over 60 | 45.2 ± 16.6 a | 62.5 (50–70.8) a | 75 (50–75) a | 61.9 ± 17.2 a | 50 (50–75) a | 50 (25–50) a |

| p-value † | 0.015 | 0.01 | 0.007 | 0.044 | 0.015 | 0.02 |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Village | 51.8 (35.7–60.7) | 68.8 (52.1–83.3) | 75 (54.2–87.5) | 68.8 (56.3–78.1) | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| A city with up to 50 thousand inhabitants. | 51.1 ± 17.3 | 64.5 ± 15.7 | 67.2 ± 20.5 | 68.8 (59.4–78.1) | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| A city with up to 100 thousand inhabitants. | 46.1 ± 10.9 | 64.4 ± 13.6 | 66.7 (58.3–75) | 64.2 ± 13.8 | 62.5 (50–75) | 50 (25–62.5) |

| A city with over 100 thousand inhabitants. | 51.4 ± 10.2 | 68.8 (54.2–75) | 69.9 ± 12 | 68 ± 10.1 | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–50) |

| p-value | 0.474 | 0.857 | 0.474 | 0.824 | 0.426 | 0.589 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 50.8 ± 12.5 b | 75 (62.5–79.2) b | 70.2 ± 19.5 a,b | 69.8 ± 10.1 b | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| Married | 52.2 ± 13.9 b | 66.7 (58.3–79.2) b | 75 (66.7–83.3) b | 69.6 ± 13.4 b | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| In a separation/divorce | 45.7 ± 12.8 b | 61.7 ± 14.1 a,b | 65 ± 20.3 a,b | 62.2 ± 13.4 a,b | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–50) |

| Widower | 34.4 ± 15.6 a | 49.2 ± 14.5 a | 45.9 (33.3–70.9) a | 50 (29.7–61) a | 50 (50–75) | 50 (25–50) |

| p-value † | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.059 | 0.066 |

| Physically active | ||||||

| Smaller than the previous year | 47.7 ± 14.8 | 62.5 (54.2–79.2) | 70.9 (58.3–83.3) | 64.1 (56.3–78.1) | 62.5 (50–75) | 50 (25–50) |

| Bigger than the previous year | 52 ± 15 | 70.8 (58.3–79.2) | 75 (66.7–75) | 69.8 ± 11.7 | 75 (75–75) | 50 (50–75) |

| p-value | 0.16 | 0.157 | 0.384 | 0.118 | <0.001 | 0.017 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 47.5 ± 17.6 | 62.5 (50–75) | 63.8 ± 19.3 | 60.7 ± 18.9 | 50 (50–75) | 50 (25–50) |

| No | 49.4 ± 14.2 | 66.7 (54.2–79.2) | 75 (58.3–83.3) | 68.8 (59.4–78.1) | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| p-value | 0.583 | 0.145 | 0.073 | 0.065 | 0.041 | 0.582 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| Everyday | ||||||

| Once a week | 41.7 ± 24.2 | 55.6 ± 21 | 61.8 ± 22.6 | 54.7 ± 21.4 | 50 ± 23.8 | 50 (50–62.5) |

| Once a month | 55.9 ± 13.8 | 79.2 (70.8–79.2) | 79.6 ± 21.7 | 71.2 ± 14.2 | 75 (75–75) | 50 (50–75) |

| Occasionally | 48.7 ± 13.9 | 66.7 (54.2–79.2) | 75 (58.3–75) | 67.6 ± 13.8 | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| Don’t drink | 50 (46.4–60.7) | 66.7 (54.2–79.2) | 75 (66.7–83.3) | 67 ± 12.9 | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| p-value | 0.31 | 0.171 | 0.094 | 0.209 | 0.051 | 0.518 |

| PSQI | ||||||

| Good sleep | 59.9 ± 12 | 79.2 (69.775–80.225) | 75 (66.7–83.3) | 74.8 ± 12.3 | 75 (68.75–75) | 50 (50–75) |

| Bad sleep | 46.4 (35.7–57.1) | 62.5 (50–75) | 75 (58.3–75) | 64.05 (56.3–75) | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.036 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| BDI | ||||||

| Moderate to severe | 30.9 ± 13.7 | 45.3 ± 11.5 | 46.4 ± 14.6 | 47 ± 14.6 | 50 (50–50) | 25 (25–50) |

| Mild to borderline | 53.4 ± 11.5 | 70.8 (62.5–79.2) | 75 (66.7–83.3) | 70.6 ±11.5 | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Physical Health | Psychological | Social Relationships | Environment | Overall QoL | Overall health | |

| Treatment line | ||||||

| 1st line | 58.9 (57.1–60.7) | 79.2 (79.2–79.2) | 87.5 (75–100) | 76.6 (75–78.1) | 62.5 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| 2nd line | 46.6 + 17.3 | 62.7 + 17.4 | 75 (54.2–79.2) | 66.2 + 18.5 | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–62.5) |

| 3rd line | 49.7 + 13.3 | 66.7 (54.2–79.2) | 75 (58.3–83.3) | 64.3 + 13.8 | 75 (50–75) | 50 (25–75) |

| 4th line | 50 + 19.2 | 75 (58.3–83.3) | 73.5 + 23.3 | 78.1 (56.3–78.1) | 75 (50–75) | 75 (50–75) |

| 5th line | 49.7 + 12.2 | 68.6 + 8.7 | 69.5 + 11.8 | 69.5 + 12 | 75 (50–75) | 47.3 + 19.6 |

| p-value | 0.512 | 0.467 | 0.578 | 0.396 | 0.933 | 0.466 |

| Prediction Parameters of QoL (n = 116) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analyzed Parameter | b Coeff. | b Error | −95% CI | +95% CI | t-Stat. | p-Value | b Stand. | b Stand. Error |

| Physical Health | ||||||||

| Age | −2.959 | 1.479 | −5.89 | −0.027 | −2.000 | 0.048 | -0.139 | 0.069 |

| BMI | −0.617 | 0.201 | −1.016 | −0.218 | −3.063 | 0.003 | −0.212 | 0.069 |

| good sleep | 8.531 | 2.44 | 3.695 | 13.367 | 3.496 | 0.001 | 0.245 | 0.07 |

| moderate to severe depression | −18.394 | 2.614 | −23.573 | −13.215 | −7.038 | <0.001 | −0.493 | 0.07 |

| Psychological | ||||||||

| BMI | −0.62 | 0.212 | −1.04 | −0.201 | −2.93 | 0.004 | −0.205 | 0.07 |

| good sleep | 5.859 | 2.607 | 0.694 | 11.024 | 2.248 | 0.027 | 0.162 | 0.072 |

| moderate to severe depression | −21.477 | 2.823 | −27.072 | −15.883 | −7.607 | <0.001 | −0.554 | 0.073 |

| Social Relationships | ||||||||

| RA durations | 0.437 | 0.154 | 0.131 | 0.742 | 2.831 | 0.006 | 0.193 | 0.068 |

| Meals per day | 4.213 | 1.338 | 1.562 | 6.865 | 3.149 | 0.002 | 0.22 | 0.07 |

| BMI | −0.477 | 0.252 | −0.976 | 0.023 | −1.892 | 0.061 | −0.13 | 0.069 |

| moderate to severe depression | −25.5 | 3.303 | −32.045 | −18.955 | −7.72 | <0.001 | −0.543 | 0.07 |

| Environment | ||||||||

| RA durations | 0.295 | 0.126 | 0.044 | 0.545 | 2.333 | 0.022 | 0.16 | 0.069 |

| Alcohol consumption, reference [everyday] | ||||||||

| Once a week | 18.704 | 11.7 | −4.489 | 41.897 | 1.599 | 0.113 | 0.374 | 0.234 |

| Once a month | 23.047 | 12.032 | −0.805 | 46.898 | 1.915 | 0.058 | 0.405 | 0.212 |

| Occasionally | 20.948 | 11.543 | −1.934 | 43.83 | 1.815 | 0.072 | 0.686 | 0.378 |

| I don’t drink alcohol | 20.971 | 11.568 | −1.961 | 43.902 | 1.813 | 0.073 | 0.659 | 0.363 |

| BMI | −0.65 | 0.209 | −1.064 | −0.236 | −3.113 | 0.002 | -0.218 | 0.07 |

| good sleep | 5.656 | 2.519 | 0.662 | 10.65 | 2.245 | 0.027 | 0.159 | 0.071 |

| Overall QoL | ||||||||

| RA durations | 0.544 | 0.176 | 0.196 | 0.892 | 3.099 | 0.002 | 0.262 | 0.085 |

| Being more physically active than the previous year | 13.288 | 3.184 | 6.981 | 19.596 | 4.174 | <0.001 | 0.353 | 0.085 |

| Overall health | ||||||||

| Minutes spent outdoors | 0.042 | 0.023 | −0.004 | 0.088 | 1.805 | 0.074 | 0.158 | 0.088 |

| BMI | −0.859 | 0.354 | −1.561 | −0.156 | −2.423 | 0.017 | −0.214 | 0.088 |

| Good sleep | 10.141 | 4.295 | 1.63 | 18.652 | 2.361 | 0.02 | 0.212 | 0.09 |

| moderate to severe depression | −10.048 | 4.657 | −19.276 | −0.821 | −2.158 | 0.033 | −0.195 | 0.091 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grygiel-Górniak, B.; Kowynia, E.; Abouzid, M.; Kwaśniewska, A.; Joks, M.; Majewska, N.; Samborski, W. Quality of Life in Long-Standing Rheumatoid Arthritis: What Can Help Apart from Treatment? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8925. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248925

Grygiel-Górniak B, Kowynia E, Abouzid M, Kwaśniewska A, Joks M, Majewska N, Samborski W. Quality of Life in Long-Standing Rheumatoid Arthritis: What Can Help Apart from Treatment? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8925. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248925

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrygiel-Górniak, Bogna, Ewelina Kowynia, Mohamed Abouzid, Anna Kwaśniewska, Maria Joks, Natalia Majewska, and Włodzimierz Samborski. 2025. "Quality of Life in Long-Standing Rheumatoid Arthritis: What Can Help Apart from Treatment? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Observational Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8925. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248925

APA StyleGrygiel-Górniak, B., Kowynia, E., Abouzid, M., Kwaśniewska, A., Joks, M., Majewska, N., & Samborski, W. (2025). Quality of Life in Long-Standing Rheumatoid Arthritis: What Can Help Apart from Treatment? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8925. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248925