First-Pass Isolation as an Independent Predictor of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Cryoballoon Ablation in Patients with Persistent Atrial Fibrillation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

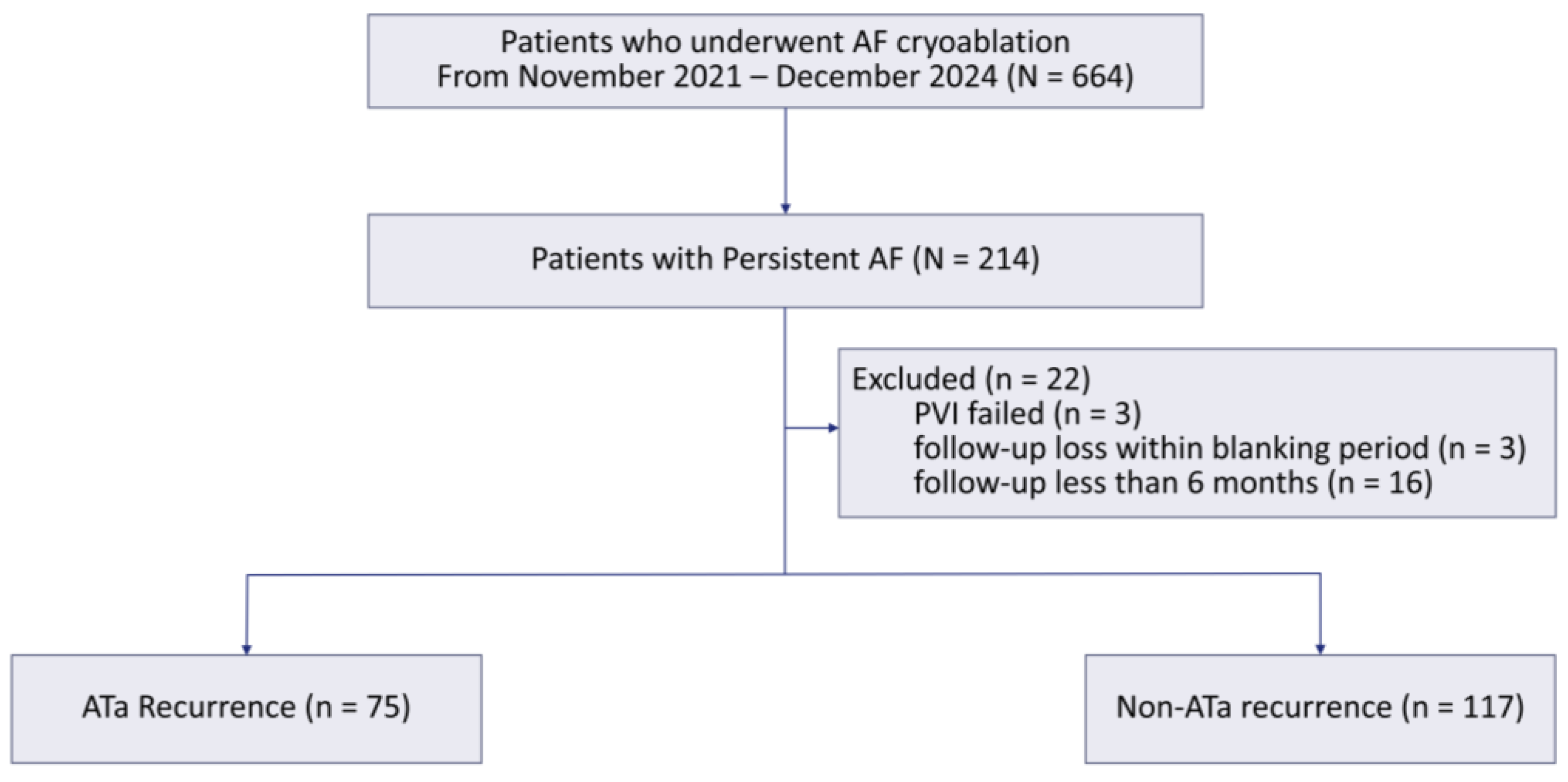

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Ablation Procedure

2.3. Data Collection and Definition

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Baseline Characteristics

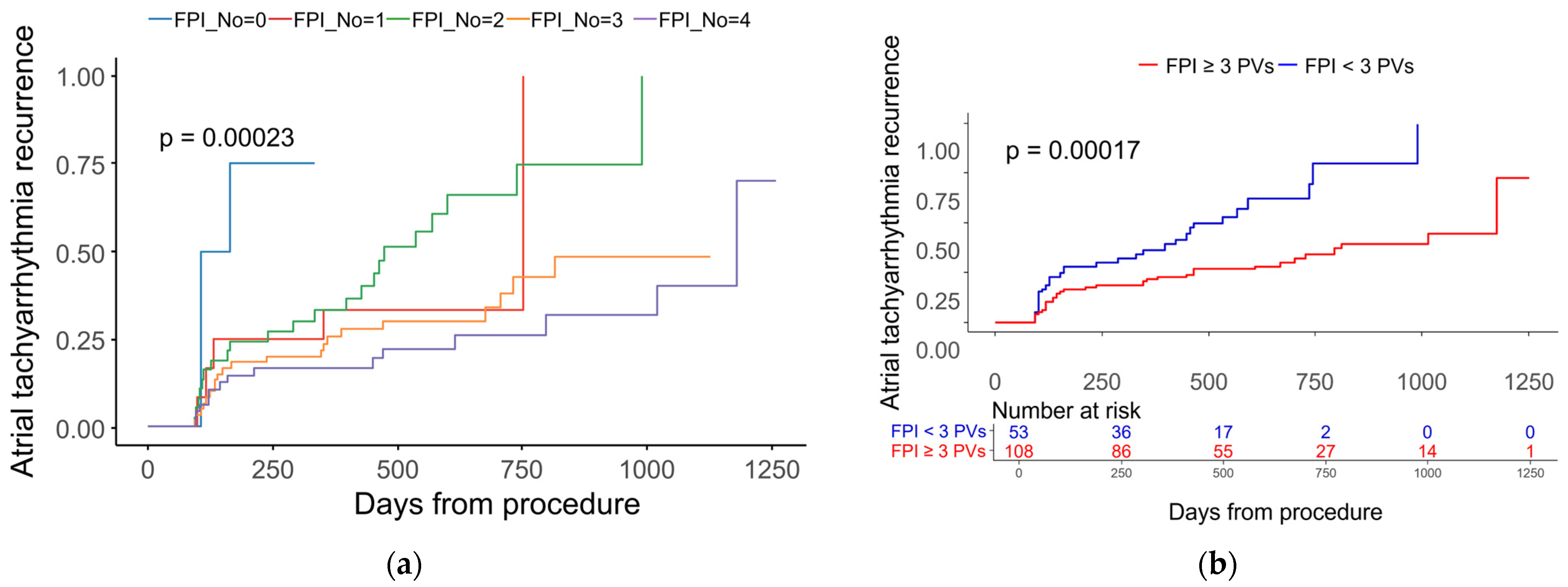

3.2. Recurrence and Procedural Outcomes

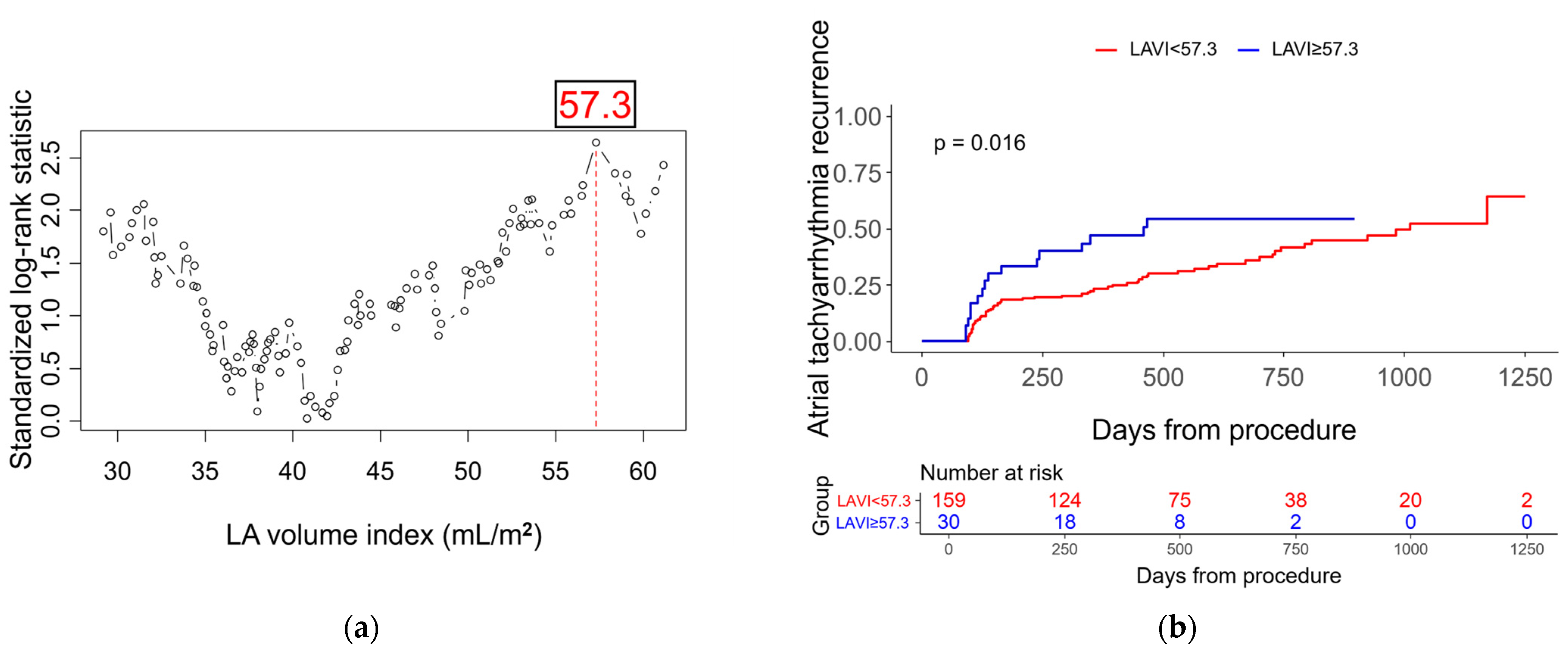

3.3. Independent Predictors of Recurrence

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| PVI | Pulmonary vein isolation |

| PeAF | Persistent AF |

| FPI | First-pass isolation |

| LAVI | Left atrial volume index |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| CBA | Cryoballoon ablation |

| ICE | Intracardiac echocardiography |

| ACT | Activated clotting time |

| ILR | Implantable loop recorder |

| RFA | Radiofrequency ablation |

| PWI | Posterior wall isolation |

References

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida, A.; Diouf, M.; Kubala, M.; Fay, F.; Burtin, J.; Lallemand, P.M.; Buiciuc, O.; Lieu, A.; Zaitouni, M.; Beyls, C.; et al. Results and Predictive Factors After One Cryoablation for Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 159, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskoboinik, A.; Moskovitch, J.T.; Harel, N.; Sanders, P.; Kistler, P.M.; Kalman, J.M. Revisiting pulmonary vein isolation alone for persistent atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm 2017, 14, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, K.R.J.; Stellbrink, C.; Murakami, M.; Drephal, C.; Oh, I.Y.; van Bragt, K.A.; Becker, D.; Anselme, S.; Todd, D.; Kaczmarek, K.; et al. Predictors of Arrhythmia Recurrence After Cryoballoon Ablation for Persistent Atrial Fibrillation: A Sub-Analysis of the Cryo Global Registry. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2025, 36, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reissmann, B.; Plenge, T.; Heeger, C.H.; Schlüter, M.; Wohlmuth, P.; Fink, T.; Rottner, L.; Tilz, R.R.; Mathew, S.; Lemeš, C.; et al. Predictors of freedom from atrial arrhythmia recurrence after cryoballoon ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation: A multicenter study. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2019, 30, 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, Y.; Inoue, K.; Tanaka, N.; Okada, M.; Tanaka, K.; Onishi, T.; Hirao, Y.; Oka, T.; Inoue, H.; Takayasu, K.; et al. Absence of first-pass isolation is associated with poor pulmonary vein isolation durability and atrial fibrillation ablation outcomes. J. Arrhythm. 2021, 37, 1468–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pinzón, J.; Waks, J.W.; Yungher, D.; Reynolds, A.; Maher, T.; Locke, A.H.; d’Avila, A.; Tung, P. Predictors of first-pass isolation in patients with recurrent atrial fibrillation: A retrospective cohort study. Heart Rhythm O2 2024, 5, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Shin, D.G.; Han, S.J.; Lim, H.E. Does isolation of the left atrial posterior wall using cryoballoon ablation improve clinical outcomes in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation? A prospective randomized controlled trial. Europace 2022, 24, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergonti, M.; Spera, F.R.; Ferrero, T.G.; Nsahlai, M.; Bonomi, A.; Tijskens, M.; Boris, W.; Saenen, J.; Huybrechts, W.; Miljoen, H.; et al. Characterization of Atrial Substrate to Predict the Success of Pulmonary Vein Isolation: The Prospective, Multicenter MASH-AF II (Multipolar Atrial Substrate High Density Mapping in Atrial Fibrillation) Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e027795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, M.; Matsuda, Y.; Uematsu, H.; Sugino, A.; Ooka, H.; Kudo, S.; Fujii, S.; Asai, M.; Okamoto, S.; Ishihara, T.; et al. Clinical impact of left atrial remodeling pattern in patients with atrial fibrillation: Comparison of volumetric, electrical, and combined remodeling. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2024, 35, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamori, S.; Ngo, L.H.; Tugal, D.; Manning, W.J.; Nezafat, R. Incremental Value of Left Atrial Geometric Remodeling in Predicting Late Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Pulmonary Vein Isolation: A Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e009793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.; Blessberger, H.; Nahler, A.; Hrncic, D.; Fellner, A.; Reiter, C.; Hönig, S.; Schmit, P.; Fellner, F.; Lambert, T.; et al. Cardiac Computed Tomography-Derived Left Atrial Volume Index as a Predictor of Long-Term Success of Cryo-Ablation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 140, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajraktari, G.; Bytyçi, I.; Henein, M.Y. Left atrial structure and function predictors of recurrent fibrillation after catheter ablation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2020, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandorfi, G.; Rodriguez-Mañero, M.; Saenen, J.; Baluja, A.; Bories, W.; Huybrechts, W.; Miljoen, H.; Vandaele, L.; Heidbuchel, H.; Sarkozy, A. Less Pulmonary Vein Reconnection at Redo Procedures Following Radiofrequency Point-by-Point Antral Pulmonary Vein Isolation with the Use of Contemporary Catheter Ablation Technologies. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2018, 4, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, A.; Russo, M.; Galeazzi, M.; Pandozi, C.; Bonanni, M.; Mariani, M.V.; Pierucci, N.; La Fazia, V.M.; Di Fusco, S.A.; Nardi, F.; et al. Impact of Ablation Energy Sources on Perceived Quality of Life and Symptom in Atrial Fibrillation Patients: A Comparative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Leng, B.; Yu, X.; Du, X.; Chu, H.; Zhou, S.; Shen, C.; Feng, M.; Jiang, Y.; Jin, H.; et al. Impact of the first-pass pulmonary vein isolation on ablation outcomes in persistent atrial fibrillation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1588716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Kwon, O.-S.; Hwang, T.; Park, H.; Yu, H.T.; Kim, T.-H.; Uhm, J.-S.; Joung, B.; Lee, M.-H.; Pak, H.-N. Using computed tomography atrial myocardial thickness maps in cryoballoon pulmonary vein isolation: The UTMOST AF II randomized clinical trial. EP Eur. 2024, 26, euae292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.V.; Matteucci, A.; Pierucci, N.; Palombi, M.; Compagnucci, P.; Bruti, R.; Cipollone, P.; Vinciullo, S.; Trivigno, S.; Piro, A.; et al. Pentaspline Pulsed Field Ablation Versus High-Power Short-Duration/Very High-Power Short-Duration Radiofrequency Ablation in Atrial Fibrillation: A Meta-Analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2025, 36, 2165–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Jiang, C.Y.; Betts, T.R.; Chen, J.; Deisenhofer, I.; Mantovan, R.; Macle, L.; Morillo, C.A.; Haverkamp, W.; Weerasooriya, R.; et al. Approaches to catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1812–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kistler, P.M.; Chieng, D.; Sugumar, H.; Ling, L.-H.; Segan, L.; Azzopardi, S.; Al-Kaisey, A.; Parameswaran, R.; Anderson, R.D.; Hawson, J.; et al. Effect of Catheter Ablation Using Pulmonary Vein Isolation With vs Without Posterior Left Atrial Wall Isolation on Atrial Arrhythmia Recurrence in Patients with Persistent Atrial Fibrillation: The CAPLA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 329, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna-Rivero, N.; Tu, S.J.; Elliott, A.D.; Pitman, B.M.; Gallagher, C.; Lau, D.H.; Sanders, P.; Wong, C.X. Anemia and iron deficiency in patients with atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Voskoboinik, A.; Gerche, A.L.; Marwick, T.H.; McMullen, J.R. Prevention of Pathological Atrial Remodeling and Atrial Fibrillation. JACC 2021, 77, 2846–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.J.; Hanna-Rivero, N.; Elliott, A.D.; Clarke, N.; Huang, S.; Pitman, B.M.; Gallagher, C.; Linz, D.; Mahajan, R.; Lau, D.H.; et al. Associations of anemia with stroke, bleeding, and mortality in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2021, 32, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, M.; Matsuda, Y.; Uematsu, H.; Sugino, A.; Ooka, H.; Kudo, S.; Fujii, S.; Asai, M.; Iida, O.; Okamoto, S.; et al. Gender Differences in Atrial Fibrosis and Cardiomyopathy Assessed by Left Atrial Low-Voltage Areas During Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2023, 203, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, F.; Silva-Teixeira, R.; Aguiar-Neves, I.; Almeida, J.G.; Fonseca, P.; Monteiro, A.V.; Oliveira, M.; Gonçalves, H.; Ribeiro, J.; Caramelo, F.; et al. Sex differences in atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm 2025, 22, E563–E571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, S.; Long, V.; Fiset, C. Higher Na+-Ca2+ Exchanger Function and Triggered Activity Contribute to Male Predisposition to Atrial Fibrillation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.; Milstein, J.; Blum, J.; Lazieh, S.; Yang, V.; Zhao, X.; Muquit, S.; Malwankar, J.; Marine, J.E.; Berger, R.; et al. Sex-based differences in safety and efficacy of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2023, 34, 1640–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, C.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yi, F. Sex differences in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation catheter ablation: A difference-in-difference propensity score matched analysis. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 46, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cersosimo, A.; Arabia, G.; Cerini, M.; Calvi, E.; Mitacchione, G.; Aboelhassan, M.; Giacopelli, D.; Inciardi, R.M.; Curnis, A. Predictive value of left and right atrial strain for the detection of device-detected atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke and implantable cardiac monitor. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 435, 133368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regmi, M.R.; Bhattarai, M.; Parajuli, P.; Botchway, A.; Tandan, N.; Abdelkarim, J.; Labedi, M. Prediction of Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation Post-ablation Based on Atrial Fibrosis Seen on Late Gadolinium Enhancement MRI: A Metaanalysis. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2023, 19, e051222211571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, M.; Matsuda, Y.; Uematsu, H.; Sugino, A.; Ooka, H.; Kudo, S.; Fujii, S.; Asai, M.; Okamoto, S.; Ishihara, T.; et al. Prognostic impact of atrial cardiomyopathy: Long-term follow-up of patients with and without low-voltage areas following atrial fibrillation ablation. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starek, Z.; Di Cori, A.; Betts, T.R.; Clerici, G.; Gras, D.; Lyan, E.; Della Bella, P.; Li, J.; Hack, B.; Zitella Verbick, L.; et al. Baseline left atrial low-voltage area predicts recurrence after pulmonary vein isolation: WAVE-MAP AF results. EP Eur. 2023, 25, euad194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cersosimo, A.; Longo Elia, R.; Condello, F.; Colombo, F.; Pierucci, N.; Arabia, G.; Matteucci, A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Vizzardi, E.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | |

|---|---|

| N = 192 | |

| Age, y | 59.7 ± 10.2 |

| Sex (male) | 156 (81.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6 ± 3.5 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 1.6 ± 1.3 |

| Diagnosis-to-ablation interval (years) | 3.3 ± 3.2 |

| Platform | |

| PolarX (Boston) | 59 (30.7) |

| Arctic Front Advance Pro (Medtronic) | 133 (69.3) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Congestive heart failure | 30 (15.6) |

| Hypertension | 84 (43.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 35 (18.2) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 31 (16.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 (5.7) |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 58.9 ± 8.3 |

| LA volume index (mL/m2) | 44.9 ± 13.6 |

| E/e′ ratio | 8.9 ± 3.4 |

| Laboratory findings | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.0 ± 1.4 |

| Estimated GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 85.8 ± 15.6 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 615.0 ± 840.6 |

| Non-Recurrence | Recurrence | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 117 (60.9) | N = 75 (39.1) | ||

| Age, y | 60.0 ± 10.2 | 59.3 ± 10.4 | 0.637 |

| Sex (male) | 94 (80.3) | 62 (82.7) | 0.710 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 ± 3.1 | 25.6 ± 4.1 | * 0.833 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 0.626 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 15 (12.8) | 15 (20.0) | 0.222 |

| Hypertension | 48 (41.0) | 36 (48.0) | 0.373 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21 (17.9) | 14 (18.7) | 1.000 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 17 (14.5) | 14 (18.7) | 0.547 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6 (5.1) | 5 (6.7) | * 0.754 |

| Diagnosis-to-ablation interval (years) | 3.0 ± 2.6 | 3.7 ± 4.0 | * 0.176 |

| Follow-up duration (days) | 631 ± 285 | 803 ± 304 | <0.001 |

| AF-free duration (days) | 631 ± 285 | 320 ± 268 | <0.001 |

| History of Previous AF ablation | 12 (10.3) | 12 (16.0) | 0.268 |

| Lesion set | 0.595 | ||

| PVI only | 24 (20.5) | 18 (24.0) | |

| PVI with additional lesions (e.g., SVC or roof) | 93 (79.5) | 57 (76.0) | |

| Procedure time (min) | 88.2 ± 21.7 | 92.0 ± 22.0 | 0.252 |

| Ablation time (min) | 57.2 ± 14.9 | 60.8 ± 16.5 | 0.126 |

| Fluoroscopic time (min) | 22.3 ± 10.1 | 22.6 ± 8.8 | 0.866 |

| PV number of achieving FPI | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 0.007 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |||

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 59.3 ± 8.3 | 58.4 ± 8.2 | 0.447 |

| LA volume index (mL/m2) | 43.5 ± 12.1 | 47.0 ± 15.5 | * 0.104 |

| E/e′ ratio | 8.8 ± 3.1 | 9.2 ± 3.8 | 0.415 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.2 ± 1.3 | 13.8 ± 1.4 | 0.041 |

| Estimated GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 86.0 ± 15.0 | 85.4 ± 16.5 | 0.789 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 555.5 ± 535.9 | 709.3 ± 1176.0 | 0.393 |

| Univariate Analysis | * Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age, per 1 year increase | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.948 | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 0.880 |

| Male | 1.14 (0.63–2.08) | 0.664 | 2.23 (1.06–4.68) | 0.034 |

| BMI, per 1 kg/m2 increase | 0.98 (0.92–1.05) | 0.571 | ||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, per 1 score increase | 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | 0.737 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Congestive heart failure | 1.41 (0.80–2.48) | 0.241 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.14 (0.73–1.80) | 0.566 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.03 (0.58–1.85) | 0.917 | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.17 (0.65–2.10) | 0.594 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.60 (0.64–3.98) | 0.312 | ||

| Diagnosis-to-ablation interval, per 1-year increase | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 0.035 | 1.08 (1.00–1.16) | 0.063 |

| History of previous AF ablation | 1.72 (0.93–3.21) | 0.086 | 1.43 (0.71–2.88) | 0.317 |

| General anesthesia | 1.05 (0.58–1.92) | 0.869 | ||

| Lesion | ||||

| PVI only | 1.28 (0.75–2.17) | 0.365 | ||

| PVI with additional lesions (e.g., SVC or roof) | 0.78 (0.46–1.33) | |||

| PV number of FPI < 3 | 2.58 (1.56–4.28) | <0.001 | 2.48 (1.48–4.16) | 0.001 |

| PV number of FPI, per 1 decrease | 1.58 (1.25–2.00) | <0.001 | ||

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||||

| LV ejection fraction, per 1% increase | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.646 | ||

| LA volume index, per 1 mL/m2 increase | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.014 | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.163 |

| LA volume index ≥ 57.3 mL/m2 | 1.96 (1.12–3.44) | 0.018 | ||

| E of e′, per 1 increase | 1.04 (0.98–1.12) | 0.212 | ||

| Hemoglobin, per 1.0 g/dL decrease | 1.19 (1.01–1.41) | 0.035 | 1.29 (1.05–1.58) | 0.015 |

| Hemoglobin < 13.8 g/dL | 1.68 (1.06–2.68) | 0.029 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, S.-J.; Park, K.-M.; On, Y.K. First-Pass Isolation as an Independent Predictor of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Cryoballoon Ablation in Patients with Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8914. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248914

Park S, Lee HJ, Kim J, Kim J, Kim JY, Park S-J, Park K-M, On YK. First-Pass Isolation as an Independent Predictor of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Cryoballoon Ablation in Patients with Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8914. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248914

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Seongjin, Hyo Jin Lee, Jiwon Kim, Juwon Kim, Ju Youn Kim, Seung-Jung Park, Kyoung-Min Park, and Young Keun On. 2025. "First-Pass Isolation as an Independent Predictor of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Cryoballoon Ablation in Patients with Persistent Atrial Fibrillation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8914. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248914

APA StylePark, S., Lee, H. J., Kim, J., Kim, J., Kim, J. Y., Park, S.-J., Park, K.-M., & On, Y. K. (2025). First-Pass Isolation as an Independent Predictor of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Cryoballoon Ablation in Patients with Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8914. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248914