The Effects of Nicardipine on Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Function in Aged Rats Following Abdominal Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Experimental Animals

2.3. Drugs and Experimental Protocol

2.4. Anaesthesia and Surgery

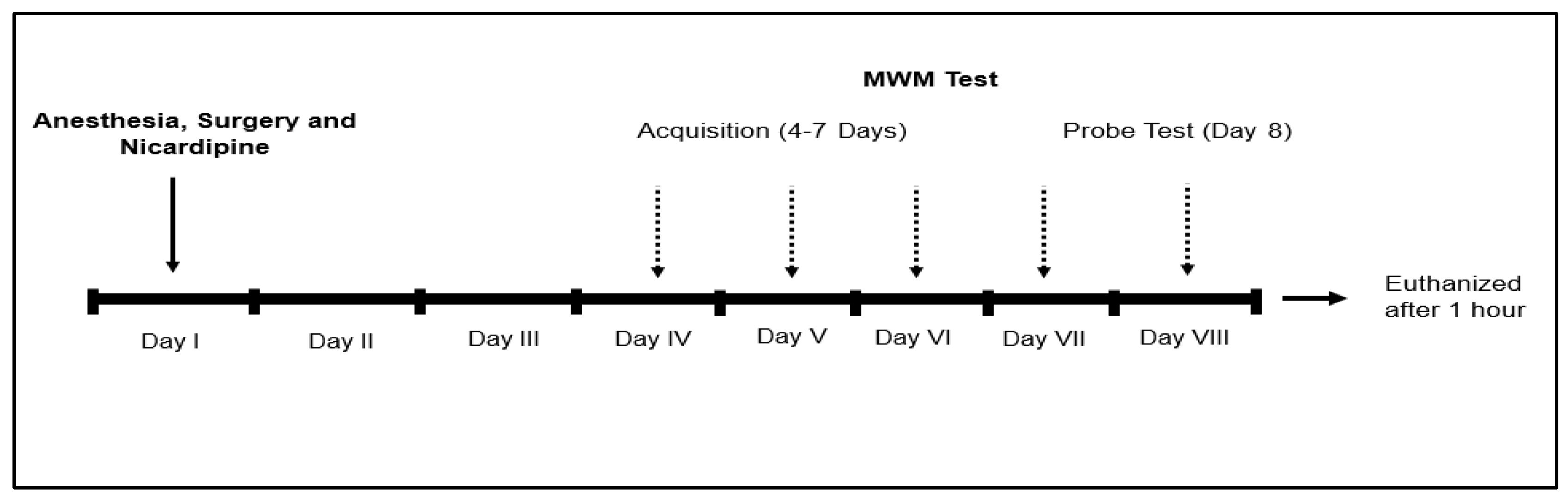

2.5. Morris Water Maze (MWM) Test

2.6. Sample Collection

2.7. Biochemical Analyses

2.7.1. ELISA Protocol

2.7.2. Western Blot Protocol

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Nicardipine on MWM Test Outcomes

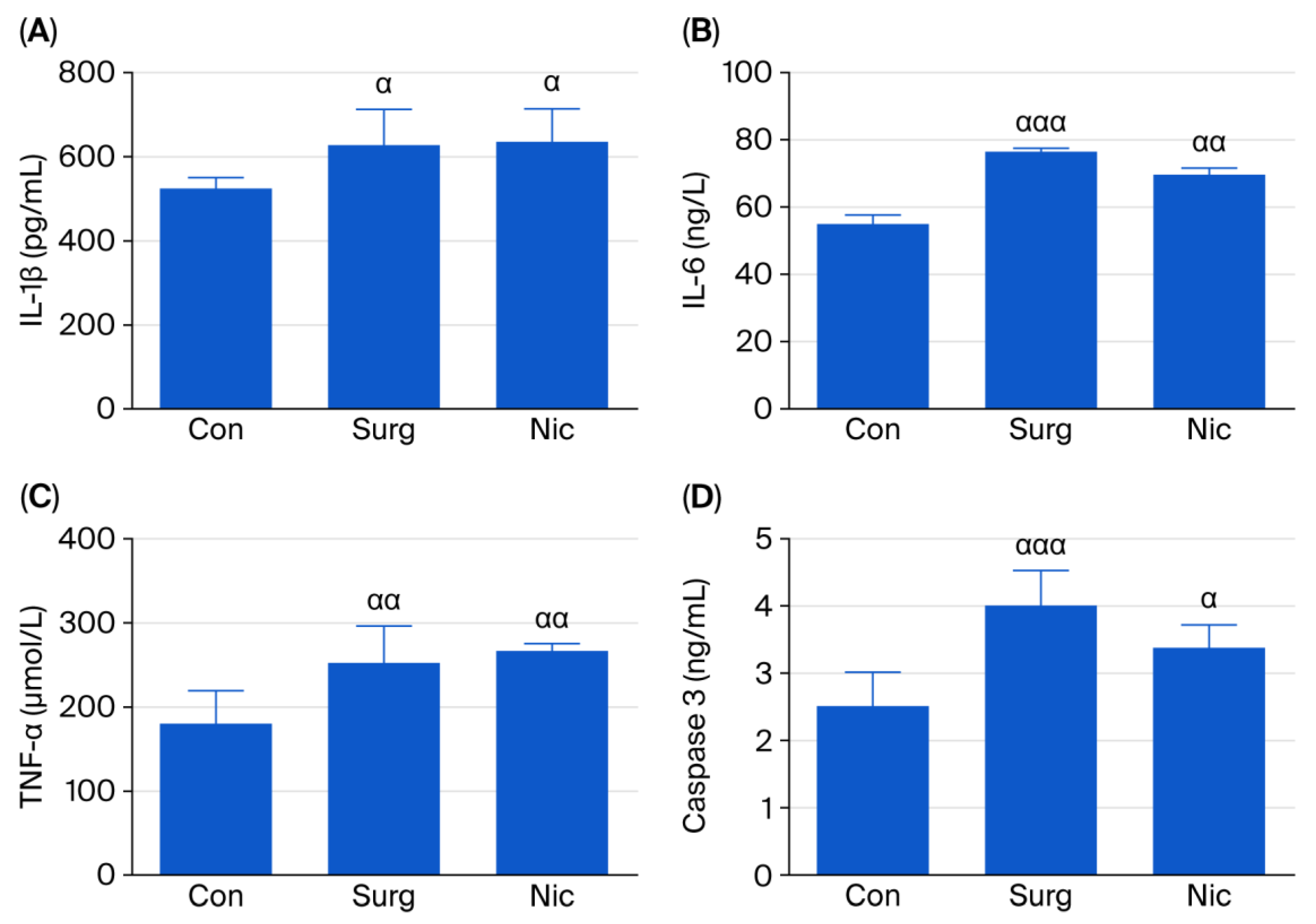

3.2. Effects of Nicardipine on IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and Caspase-3 Levels in the Hippocampus

3.2.1. ELISA Analysis

3.2.2. Western Blot Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| POCD | Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction |

| MWM | Morris Water Maze Test |

| LTCC | L-Type Calcium Channel |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneally |

| MAOA | Monoamine Oxidase A |

References

- Needham, M.J.; Webb, C.E.; Bryden, D.C. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction and dementia: What we need to know and do. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017, 119, i115–i125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evered, L.A.; Silbert, B.S. Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction and Noncardiac Surgery. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavynia, S.A.; Goldstein, P.A. The Role of Neuroinflammation in Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction: Moving from Hypothesis to Treatment. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Liu, Q.; Deng, R.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing hip arthroplasty. Psychogeriatrics 2020, 20, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Kang, Y.; Qin, S.; Chai, J. Neuroinflammation as the Underlying Mechanism of Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 843069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, W.; Wang, L.; Zhu, C.; Cui, S.; Wang, T.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, P. Unraveling the role and mechanism of mitochondria in postoperative cognitive dysfunction: A narrative review. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travica, N.; Lotfaliany, M.; Marriott, A.; Safavynia, S.A.; Lane, M.M.; Gray, L.; Veronese, N.; Berk, M.; Skvarc, D.; Aslam, H.; et al. Peri-Operative Risk Factors Associated with Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction (POCD): An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, R.S.; Wang, K.; Wang, Z.L. Sevoflurane anesthesia alters cognitive function by activating inflammation and cell death in rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 15, 4127–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Z.; Tianbao, Y.; Yanan, L.; Xi, X.; Jinhua, H.; Qiujun, W. Pre-treatment with nimodipine and 7.5% hypertonic saline protects aged rats against postoperative cognitive dysfunction via inhibiting hippocampal neuronal apoptosis. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 321, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmrich, V.; Eckert, A. Calcium channel blockers and dementia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 169, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, Z.D.; Lee, A.S.; Rajadhyaksha, A.M. L-type Ca2+ channels in mood, cognition and addiction: Integrating human and rodent studies with a focus on behavioural endophenotypes. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 5823–5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navakkode, S.; Liu, C.; Soong, T.W. Altered function of neuronal L-type calcium channels in ageing and neuroinflammation: Implications in age-related synaptic dysfunction and cognitive decline. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 42, 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Wan, H.; Pan, H.; Xu, Y. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction—Current research progress. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1328790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uryash, A.; Mijares, A.; Lopez, C.E.; Adams, J.A.; Allen, P.D.; Lopez, J.R. Post-Anesthesia Cognitive Dysfunction in Mice Is Associated with an Age-Related Increase in Neuronal Intracellular [Ca2+]—Neuroprotective Effect of Reducing Intracellular [Ca2+]: In Vivo and In Vitro Studies. Cells 2024, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Yin, C.; Xin, X.; Guo, Y.; Gao, F.; Huo, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q. Pretreatment with nimodipine reduces incidence of POCD by decreasing calcineurin mediated hippocampal neuroapoptosis in aged rats. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Lange, F.; Xia, Y.; Chertavian, C.; Cabolis, K.; Sajic, M.; Werring, D.J.; Tachtsidis, I.; Smith, K.J. Nimodipine Protects Vascular and Cognitive Function in an Animal Model of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Stroke 2024, 55, 1914–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taya, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Fujiwara, M. Nimodipine improves the disruption of spatial cognition induced by cerebral ischemia. Physiol. Behav. 2000, 70, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haile, M.; Limson, F.; Gingrich, K.; Li, Y.-S.; Quartermain, D.; Blanck, T.; Bekker, A. Nimodipine Prevents Transient Cognitive Dysfunction After Moderate Hypoxia in Adult Mice. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2009, 21, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.L.; Zheng, S.L.; Dong, F.R.; Wang, Z.M. Nimodipine Improves Regional Cerebral Blood Flow and Suppresses Inflammatory Factors in the Hippocampus of Rats with Vascular Dementia. J. Int. Med. Res. 2012, 40, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, M.; Galoyan, S.; Li, Y.-S.; Cohen, B.H.; Quartermain, D.; Blanck, T.; Bekker, A. Nimodipine-Induced Hypotension but Not Nitroglycerin-Induced Hypotension Preserves Long- and Short-Term Memory in Adult Mice. Anesth. Analg. 2012, 114, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.-R.; Chang, P.-C.; Yeh, W.-L.; Lee, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-F.; Lin, C.; Lin, H.-Y.; Liu, Y.-S.; Wu, C.Y.-J.; Ko, P.-Y.; et al. Anti-Neuroinflammatory Effects of the Calcium Channel Blocker Nicardipine on Microglial Cells: Implications for Neuroprotection. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, J.; López-Arrieta, J. Nimodipine for primary degenerative, mixed and vascular dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002, 2002, CD000147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Wang, P.; Shen, H.; Zuo, L.; Pan, Y.; et al. The efficacy and safety of nimodipine in acute ischemic stroke patients with mild cognitive impairment: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-H.; Yang, L.; Sun, D.-F.; Wu, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, R.-C.; Wang, L.-J. Effects of vasodilator and esmolol-induced hemodynamic stability on early post-operative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients: A randomized trial. Afr. Health Sci. 2017, 16, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Choi, S.H.; Lee, S.J.; Jung, Y.-S.; Shin, Y.-S.; Jun, D.B.; Hwang, K.H.; Liu, J.; Kim, K.J. Nitroglycerin- and Nicardipine-Induced Hypotension Does Not Affect Cerebral Oxygen Saturation and Postoperative Cognitive Function in Patients Undergoing Orthognathic Surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 2104–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomassoni, D.; Lanari, A.; Silvestrelli, G.; Traini, E.; Amenta, F. Nimodipine and Its Use in Cerebrovascular Disease: Evidence from Recent Preclinical and Controlled Clinical Studies. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2008, 30, 744–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, Y.; Tang, S.; Guo, Y.; Ma, D.; Jiang, X. Mechanism of nimodipine in treating neurodegenerative diseases: In silico target identification and molecular dynamic simulation. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1549953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadan, O.; Jeong, Y.; Cohen-Sadan, S.; Sathialingam, E.; Buckley, E.M.; Kandiah, P.A.; Grossberg, J.A.; Asbury, W.; Jusko, W.J.; Samuels, O.B. Cerebrospinal Fluid Pharmacokinetics of Nicardipine Following Intrathecal Administration in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Patients. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 64, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kocaoglu, N.; Demir, H.F.; Ugun, F.; Aksoz, E.; Atik, B.; Bıcakcıoglu, M.; Sagir, O.; Koroglu, A. The Effects of Nicardipine on Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Function in Aged Rats Following Abdominal Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8912. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248912

Kocaoglu N, Demir HF, Ugun F, Aksoz E, Atik B, Bıcakcıoglu M, Sagir O, Koroglu A. The Effects of Nicardipine on Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Function in Aged Rats Following Abdominal Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8912. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248912

Chicago/Turabian StyleKocaoglu, Nazan, Hafize Fisun Demir, Fatih Ugun, Elif Aksoz, Bulent Atik, Murat Bıcakcıoglu, Ozlem Sagir, and Ahmet Koroglu. 2025. "The Effects of Nicardipine on Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Function in Aged Rats Following Abdominal Surgery" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8912. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248912

APA StyleKocaoglu, N., Demir, H. F., Ugun, F., Aksoz, E., Atik, B., Bıcakcıoglu, M., Sagir, O., & Koroglu, A. (2025). The Effects of Nicardipine on Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Function in Aged Rats Following Abdominal Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8912. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248912