1. Introduction

The scarring resulting from trauma, surgery, or burns can profoundly affect physical appearance and psychosocial well-being. Accordingly, effective scar management remains a critical challenge in reconstructive and aesthetic medicine [

1,

2]. Among the available treatment modalities, fractional laser therapy has emerged as one of the most effective minimally invasive options for improving scar texture, color, and pliability [

3,

4,

5].

Fractional laser systems are broadly categorized into ablative and non-ablative types. Ablative lasers, such as carbon dioxide (CO

2) and erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) devices, vaporize the epidermis to induce dermal remodeling but are associated with prolonged recovery times and an increased risk of adverse effects [

6,

7]. In contrast, non-ablative fractional lasers, including erbium-doped glass (Er:Glass, 1550 nm) systems, selectively target dermal microthermal columns while preserving the epidermal barrier [

4]. This mechanism produces controlled thermal injury that stimulates neocollagenesis with minimal downtime, making non-ablative approaches particularly advantageous for Asian skin types, which are more prone to post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation [

8,

9]. Non-ablative fractional photothermolysis is known to generate controlled microthermal zones within the dermis, where collagen denaturation, thermal diffusion, and subsequent extracellular matrix remodeling occur in a heat-dependent manner [

10]. These thermal dynamics form the biological foundation for temperature-guided approaches in non-ablative laser therapy.

Despite their widespread clinical use, the intraprocedural thermal dynamics of non-ablative fractional lasers remain poorly characterized [

10,

11]. Early experimental work demonstrated that fractional photothermolysis generates sharply demarcated microthermal zones with predictable patterns of dermal coagulation and epidermal sparing, providing mechanistic insight into heat-dependent tissue remodeling [

12]. Building on these foundational observations, current treatment protocols still rely largely on empirically determined energy settings, without real-time feedback on cutaneous temperature or tissue response [

4,

13]. Because both treatment efficacy and safety are closely dependent on the degree of thermal diffusion within the dermis, an objective method for monitoring temperature changes during treatment could significantly enhance treatment precision and patient safety [

10,

14,

15]. Previous optical and dermatologic studies have emphasized that the extent of intradermal heating is a critical determinant of both efficacy and safety during fractional laser procedures, underscoring the need for objective real-time monitoring [

14,

16]. Thermal monitoring has increasingly been recognized as an important component of safe and effective energy-based treatment, as it provides physiologic information that cannot be obtained through visual assessment alone. Several investigations have demonstrated the utility of infrared thermography for visualizing cutaneous heat distribution during energy-based procedures, highlighting its potential as a real-time adjunct to guide energy delivery. Despite these advances, temperature-guided optimization remains underexplored in non-ablative fractional laser therapy, reinforcing the need for systematic evaluation of intraprocedural thermal behavior.

Forward-looking infrared (FLIR) thermography enables non-contact, high-resolution measurement of skin-surface temperature distribution in real time [

16]. Initially developed for industrial and military purposes, FLIR imaging has since been applied in various medical settings, including flap perfusion monitoring, burn-depth assessment, and evaluation of peripheral circulation [

14,

17]. Medical thermography has additionally been explored for characterizing cutaneous thermal gradients, estimating subsurface perfusion, and evaluating temperature-dependent tissue responses, supporting its relevance as a physiological monitoring tool during energy-based dermatologic procedures [

17]. Infrared thermography has also been validated in clinical wound assessment, with systematic reviews demonstrating its utility for estimating burn-depth progression and healing potential [

18]. These data further support the relevance of thermal imaging as a physiologic monitoring tool in dermatologic procedures. Its incorporation into laser dermatology offers the potential to dynamically visualize thermal profiles, allowing clinicians to maintain a therapeutic temperature range that promotes collagen remodeling while avoiding excessive thermal injury [

10,

15].

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to quantify skin-surface temperature changes during Er:Glass non-ablative fractional laser treatment using real-time FLIR thermography and to correlate these thermal dynamics with early clinical outcomes. By exploring whether a clinically meaningful “thermal window” may be identified as an indicator of safe and effective treatment response, we sought to provide preliminary, evidence-based insight into temperature-guided non-ablative fractional laser therapy in scar management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This retrospective clinical study was conducted in the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Korea. Medical records of patients who underwent non-ablative fractional Er:Glass laser treatment for scar management between March 2023 and February 2024 were reviewed. The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Hospital (IRB No. 2025-03), and all procedures adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Patient Selection and Eligibility Criteria

A total of 61 patients who received non-ablative fractional Er:Glass laser treatment for surgical, traumatic, or burn scars during the study period were screened. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 55 patients were included in the final analysis. Patients presented with scars located in different anatomical regions (face, trunk, and extremities). Anatomical site was documented for all cases and incorporated as a covariate in subsequent statistical analyses to account for site-related variability.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) clinically stable scars older than six months, (2) no additional scar treatment within the preceding three months, and (3) availability of complete thermal imaging and follow-up data for at least one month. Exclusion criteria were: (1) active infection or inflammation at the treatment site, (2) systemic corticosteroid or immunosuppressant use, (3) pregnancy or lactation, and (4) history of impaired wound healing or hypertrophic scarring unrelated to the treated lesion. Clinical records were independently reviewed by two investigators to confirm data completeness and consistency.

2.3. Laser Treatment Protocol

All patients received a single session of non-ablative fractional Er:Glass laser therapy (Sellas EVO, Dinona, Seoul, Republic of Korea; wavelength 1550 nm). A topical anesthetic cream containing 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine (EMLA®, AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK) was applied evenly for 30 min and removed prior to irradiation.

Laser settings were adjusted based on scar type and anatomical location. Facial scars were typically treated at 2 mJ, whereas thicker or hypertrophic scars on the trunk or extremities received 2–4 mJ. Spot density was standardized at 100 pulses per area, and the laser was applied ten times in moving (continuous-scanning) mode with approximately 50% overlap. The beam pattern was set to an elliptical shape and adjusted according to the scar size and contour, extending slightly beyond the visible scar margin to ensure uniform dermal coverage.

Post-treatment care consisted of cooling with sterile saline-soaked gauze for five minutes, followed by application of a mild moisturizer and sunscreen. No occlusive dressing or adjunctive medication was used. A representative interface of the Er:Glass laser system is shown in

Figure 1.

2.4. Thermal Imaging Acquisition and Calibration

Thermal imaging was performed using a handheld forward-looking infrared camera (FLIR C5, Teledyne FLIR, Wilsonville, OR, USA; thermal sensitivity ≤ 0.1 °C; resolution 160 × 120 pixels). Images were obtained at three time points: immediately before topical anesthesia (T0), after 30 min of anesthetic application (T1), and immediately post-treatment (T2). T2 images were obtained immediately after laser irradiation and prior to the 5 min saline cooling step to ensure that the measurement reflected the actual laser-induced temperature elevation. The camera was positioned 30 cm from the skin at a 90° angle. Room temperature (22–24 °C) and relative humidity (40–50%) were controlled to minimize environmental variability.

Skin emissivity was set to 0.98. Images were analyzed using FLIR Tools software (version 6.4; Teledyne FLIR, USA). A circular region of interest approximately 1 cm in diameter was placed at the scar center. Mean surface temperature was recorded, and post-treatment temperature change (ΔT2) was defined as T2 minus T0. We used T0 (pre-anesthesia baseline) as the reference point because topical anesthesia can transiently alter skin temperature through cooling effects and occlusion, making T1 an unreliable baseline for measuring true laser-induced thermal elevation. Therefore, ΔT2 = T2 − T0 was selected to more accurately reflect the physiologic thermal response to laser irradiation. All images were captured by a single operator, and discrepancies were jointly verified and resolved by consensus with a second investigator.

2.5. Clinical and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

Clinical assessments were performed at baseline, one week, and one month post-treatment. Standardized digital photographs were taken under identical lighting and positioning conditions. Scar area was quantified using ImageJ software version 1.53 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and percentage reduction from baseline was calculated.

Objective scar quality was assessed using the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), which evaluates pigmentation, vascularity, pliability, and height. Two independent board-certified plastic surgeons, blinded to treatment parameters, scored each case, and mean values were used for analysis.

Subjective metrics included pain measured by a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) and patient satisfaction assessed on a 5-point Likert scale. All evaluations were conducted at the same scheduled follow-up visits.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Changes in temperature and scar-related variables over time were evaluated using repeated-measures analysis of variance and paired t-tests. Group comparisons of ΔT2 according to scar type (linear vs. hypertrophic) and anatomical location (face vs. extremities/trunk) were performed using independent t-tests. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess associations between ΔT2 and VSS score changes, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the correlation estimates. Linear regression was performed to identify predictors of scar improvement, including energy level, anatomical location, and ΔT2. Two-tailed p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. No missing data were identified for primary outcomes.

4. Discussion

This study suggested that non-ablative fractional Er:Glass laser treatment at 1550 nm was associated with early improvements in scar appearance, while real-time FLIR thermography was used to monitor surface thermal response during treatment. Quantitative thermal mapping showed heterogeneous post-treatment temperature elevations, and an exploratory range (approximately 1.5–2.5 °C) derived from representative cases was associated with early clinical improvements in scar texture, color uniformity, and Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) scores. FLIR monitoring enabled objective visualization of surface thermal distribution without contact, offering immediate feedback on energy delivery [

16]. FLIR thermography provides an indirect approximation of subsurface dermal heating rather than a direct measurement. Because surface temperature can be influenced by perfusion, epidermal cooling, and tissue optical properties, ΔT

2 should be interpreted as an inferential indicator of thermal response rather than a precise quantification of intradermal heat. All patients recovered uneventfully without serious adverse events such as blistering or pigmentary change. Together, these findings suggest that ΔT

2 may serve as a potential parameter reflecting surface thermal response during non-ablative fractional laser therapy and highlight the possible relevance of real-time thermal feedback as an exploratory monitoring framework. Although the mean ΔT

2 across the cohort was 1.3 °C, this reflects an overall average that includes many scars with lower thermal responses; the proposed 1.5–2.5 °C range was therefore derived from individual cases demonstrating favorable early remodeling and should be interpreted as an exploratory trend rather than a definitive threshold. Importantly, the present data do not establish the 1.5–2.5 °C range as a therapeutic target, as no meaningful efficacy gradient within this interval could be identified.

Fractional laser systems are well recognized for improving scars through collagen remodeling and neocollagenesis [

4,

5]. While ablative fractional lasers (CO

2, Er:YAG) provide pronounced textural improvement, they are often associated with prolonged erythema and downtime due to epidermal ablation [

6,

7]. By contrast, non-ablative systems—especially the 1550 nm Er:Glass laser—provide controlled sub-epidermal heating while preserving epidermal integrity, resulting in faster recovery and a lower risk of post-inflammatory pigmentation [

8,

19]. The current findings align with previous reports demonstrating improvements in scar pliability, vascularity, and pigmentation with minimal adverse events [

11,

19], but expand upon them by incorporating FLIR thermography to characterize thermal dynamics and provide physiological context for heating-induced remodeling. Recent clinical studies have also reported favorable outcomes of 1550 nm Er:Glass fractional photothermolysis for improving scar characteristics and dermal texture, particularly in atrophic and treatment-resistant lesions [

20]. Our findings are consistent with these observations and extend them by providing quantitative thermal-response data obtained through real-time infrared imaging. This real-time approach addresses a persistent gap in the literature regarding standardized intra-treatment thermal monitoring [

10,

14,

16]. The observed relationship between moderate ΔT

2 elevation and early improvement indicates an exploratory thermal range that may be associated with safe collagen remodeling [

10], providing preliminary support for temperature-informed monitoring rather than defining a fixed threshold [

15,

21]. The potential biological basis of this thermal response may relate to well-established heat-induced remodeling pathways: sub-epidermal heating can induce reversible collagen denaturation and contraction, trigger fibroblast activation, and promote subsequent neocollagenesis. Moderate thermal stress is also known to upregulate heat-shock proteins, which facilitate extracellular matrix repair and regulate collagen synthesis. In non-ablative fractional systems, microthermal zones created by controlled optical absorption and thermal diffusion act as focal points for dermal regeneration, enabling matrix turnover while sparing the epidermis [

5]. However, FLIR thermography provides only an indirect approximation of subsurface dermal heating rather than a direct measurement. Surface temperature is influenced by multiple physiological variables—including blood flow, epidermal thickness, hydration, and local cooling—and therefore may not perfectly reflect the true intradermal thermal dose. Accordingly, the association between ΔT

2 and remodeling should be interpreted as an inferential relationship, and future validation using ultrasonography, thermal modeling, or histologic correlation will be necessary to clarify the correspondence between surface and subsurface thermal behavior.

Table 6 situates the present findings within existing literature by comparing fractional laser systems. Non-ablative devices such as the 1550 nm Er:Glass laser achieve remodeling comparable to ablative systems but with shorter downtime and fewer complications [

5,

7,

19].

These comparative data highlight the need for standardized definitions of downtime and objective recovery metrics [

6,

13]. Incorporating FLIR-based temperature elevation may provide a physiologic reference point to refine downtime classification, improve pre-treatment counseling, and support individualized energy titration, although its role remains exploratory [

15,

16].

The magnitude of dermal heating emerged as a key determinant of efficacy and safety. A consistent post-treatment temperature elevation (ΔT

2 ≈ 1.5–2.5 °C) may represent an exploratory sub-epidermal thermal range potentially associated with collagen remodeling, while remaining below thresholds associated with epidermal protein denaturation [

10,

13,

22]. Rather than relying solely on subjective clinical cues such as erythema or edema, ΔT

2 measurement may offer a quantifiable reference point for estimating energy delivery in real time [

4,

13], although its predictive value remains limited [

16].

FLIR-guided feedback also enables individualized energy titration according to scar thickness, anatomical site, and vascularity—factors known to influence optical absorption and thermal diffusion [

4,

23]. Instead of establishing ΔT

2 as a biomarker, these findings suggest that it may function as a preliminary physiologic parameter to guide temperature-informed treatment adjustment, with further evidence required to determine its reproducibility across laser systems and operators [

10,

21]. Taken together, controlled temperature elevation may be associated with favorable remodeling, while maintaining epidermal integrity [

4,

22].

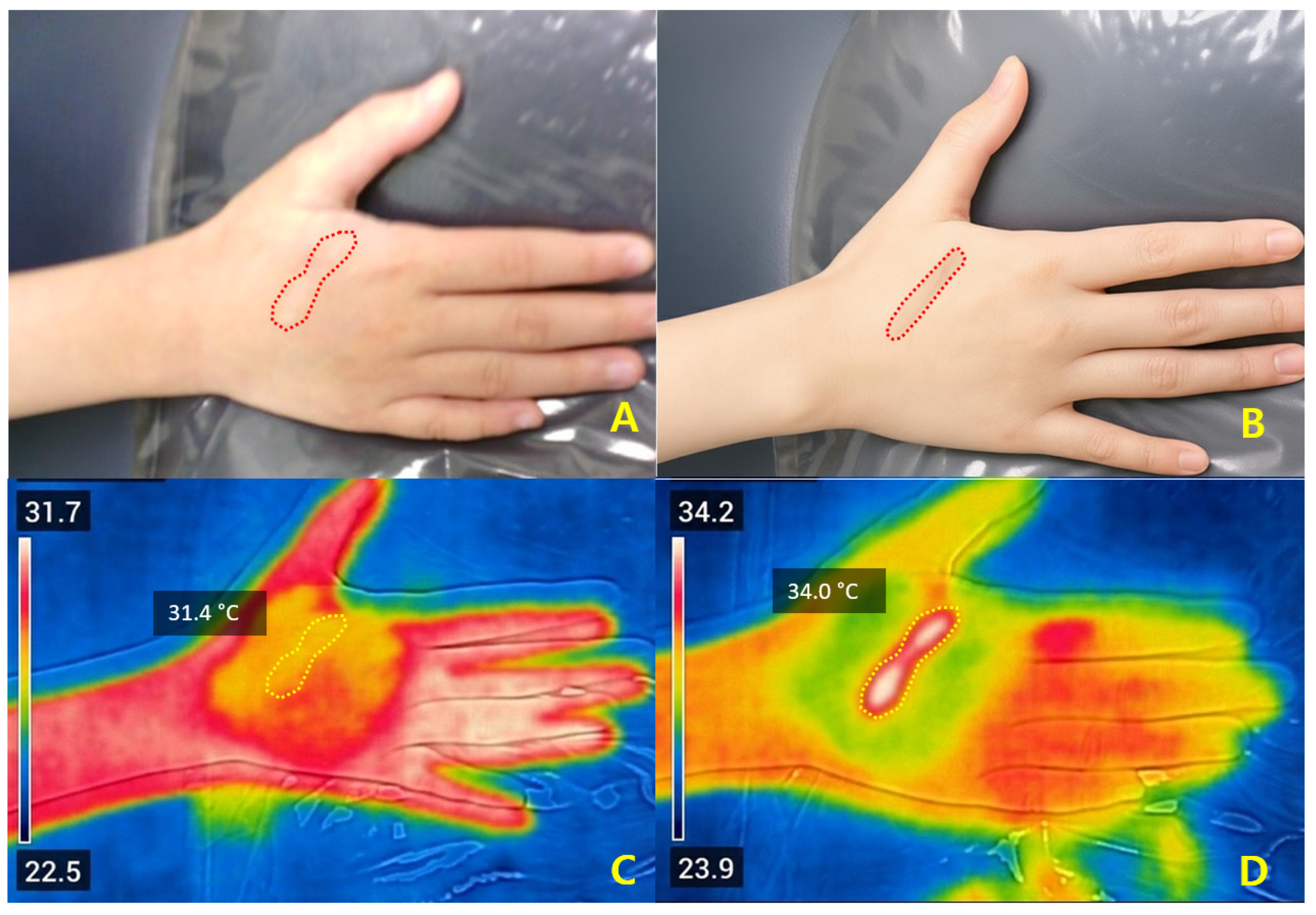

Because non-ablative fractional laser treatment produces minimal immediate visual changes during irradiation, it is often difficult to judge the adequacy of treatment by appearance alone. FLIR thermography complements this limitation by visualizing real-time thermal distribution, which may assist in achieving appropriate surface thermal response, though further validation is needed. In addition, the irradiation area (approximately 5–10 mm in diameter) can be adjusted according to individual scar morphology, enabling a personalized and reproducible treatment approach.

Real-time thermal imaging showed safe and localized surface temperature elevation. Baseline temperature increased from 32.4 ± 0.9 °C to 33.7 ± 0.7 °C immediately after irradiation (ΔT

2 = +1.3 ± 0.6 °C,

p < 0.001). Higher ΔT

2 values were noted in thicker and hypertrophic scars (+1.6 ± 0.5 °C) versus thin linear scars (+1.0 ± 0.4 °C,

p = 0.02), and in extremities/trunk compared with facial scars, reflecting anatomical differences in dermal thickness and perfusion [

4,

23,

24,

25]. A moderate temperature rise correlated with early clinical improvement (

r = 0.42,

p = 0.003), indicating an association rather than a predictive relationship [

10,

21,

22]. Because topical anesthesia can transiently lower skin temperature, T

0 was used as the baseline reference to isolate laser-associated temperature elevation and avoid confounding by anesthesia-related cooling. The observed association between ΔT

2 and early improvement reflects short-term remodeling only, and further long-term follow-up is required to determine whether these early changes translate into sustained clinical benefit.

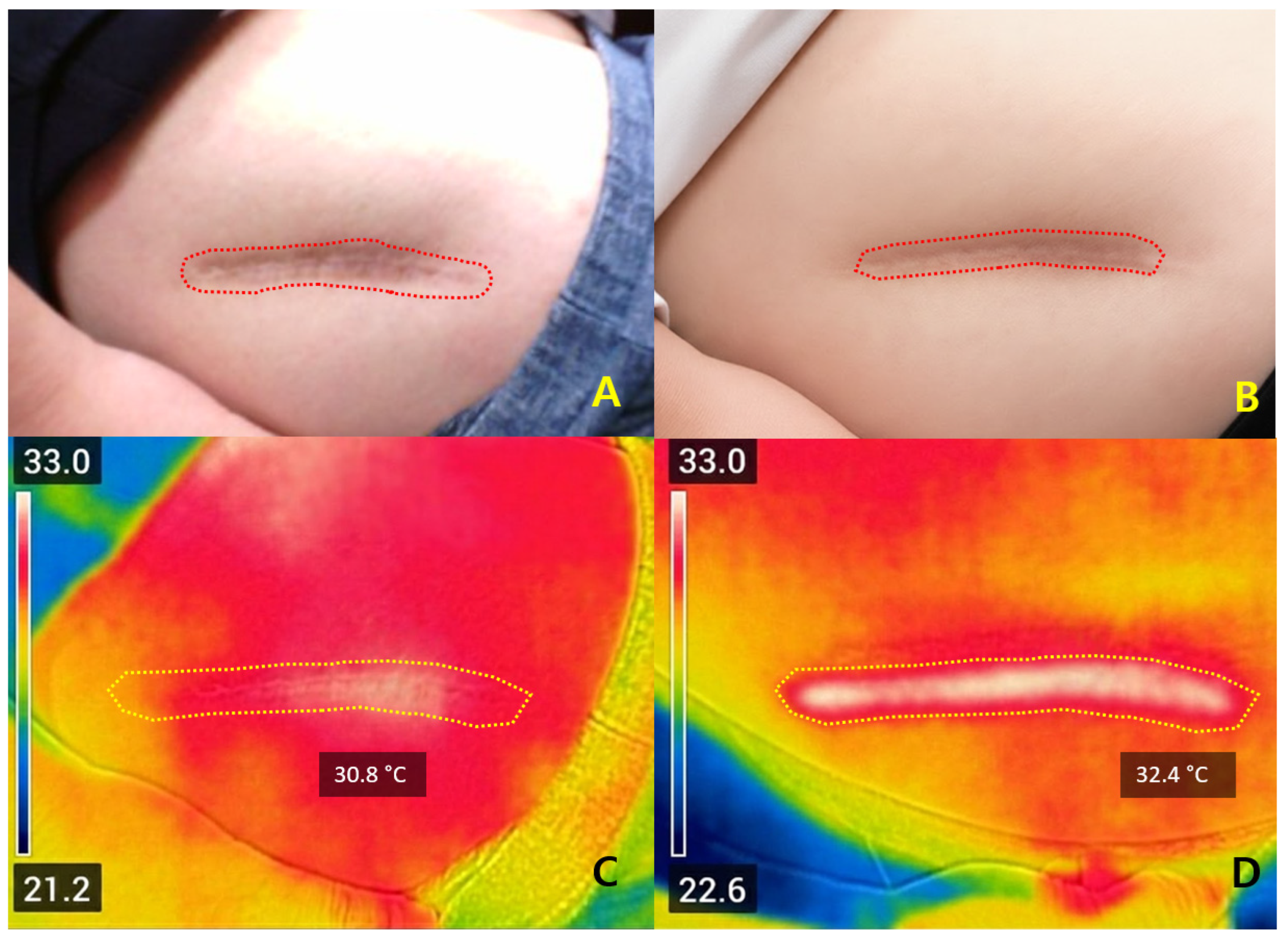

Representative cases illustrated that ΔT

2 values between +1.4 °C and +2.6 °C were associated with favorable early improvement without complications. Safety outcomes again support that ΔT

2 within this moderate range may be compatible with adequate dermal stimulation without apparent complications, while preventing excessive injury [

10,

16,

22]. Compared with ablative systems—typically requiring 5–10 days of downtime—Er:Glass treatment achieved remodeling with only 1–3 days of recovery and minimal risk of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation [

5,

7,

19]. FLIR feedback may help maintain energy delivery within a provisional thermal range, but further prospective validation is warranted [

15,

16]. Although these findings do not establish a definitive threshold, they suggest that ΔT

2 within the 1.5–2.5 °C range may serve as an exploratory indicator of favorable early response. FLIR-assisted Er:Glass therapy may therefore offer a preliminary framework for temperature-informed monitoring, although further validation is required.

Several limitations merit consideration. Given the retrospective, single-center design and the absence of a control group, the evidence provided by this study should be regarded as preliminary and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory, and the findings must therefore be interpreted with appropriate caution. This retrospective single-center study may introduce selection bias and limit generalizability, although standardized treatment and imaging protocols enhance internal validity. Importantly, the retrospective design relied on non-standardized treatment parameters, including variations in energy settings, pass numbers, and density, all of which may act as potential confounding factors. Because of these methodological constraints and the absence of a control group, the association observed between post-treatment temperature elevation and early clinical improvement cannot be interpreted as causal. Consequently, the proposed thermal window should be regarded as exploratory rather than definitive. The one-month follow-up focused on early remodeling; longer-term evaluation over 6–12 months is necessary to determine sustained improvement. Given this limited follow-up period, the durability of collagen remodeling and the persistence of clinical improvement remain unknown, and the predictive value of ΔT

2 for long-term outcomes cannot be concluded from the present data. Because scar maturation occurs over several months, the present findings cannot determine whether the early ΔT

2–response relationship persists over 3, 6, or 12 months. Thus, the long-term predictive value of ΔT

2 cannot be determined from the present dataset. FLIR thermography measures surface temperature and does not directly reflect subsurface heating; however, prior optical modeling suggests a potential relationship between surface and dermal thermal behavior. As FLIR measures only surface temperature, the correspondence between ΔT

2 and true intradermal heating remains indirect and requires further validation. Additionally, thermal image acquisition and ROI placement—although performed by a single operator to ensure consistency—may still be subject to operator dependence, which could introduce measurement variability. Topical anesthesia may also transiently alter surface temperature through cooling or occlusive effects, potentially affecting pre-treatment baseline values despite our use of T

0 to minimize this source of bias. Future work incorporating histological or ultrasonographic validation would strengthen these observations [

26]. The absence of a control group limits direct comparison across energy settings or systems; future prospective studies with randomized controlled designs, predefined laser parameters, and comparison groups will be essential to validate whether maintaining a target ΔT

2 truly leads to superior and durable clinical outcomes. Multicenter investigations incorporating standardized protocols will further improve generalizability and help establish ΔT

2 as a potential treatment-guiding parameter rather than a fully validated biomarker. Lastly, representative clinical photographs were obtained from routine clinical records and therefore exhibit natural variability in lighting, positioning, and scale, which may limit the objectivity of visual comparison across time points.