Comparative Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity of Antiseptics and Commercial Mouthwashes Against Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antiseptics

2.2. Porphyromonas gingivalis Strain

2.3. Minimal Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC)

2.4. Clinical Efficiency of MIC (CEMIC)

- CEMIC < 0.1 indicated high clinical efficiency,

- values between 0.1 and 0.9 were considered to reflect moderate efficiency,

- while values > 0.9 suggested low clinical usefulness of the compound at the tested concentration.

2.5. Minimal Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

2.6. Antibiofilm Effects

2.6.1. Crystal Violet Method

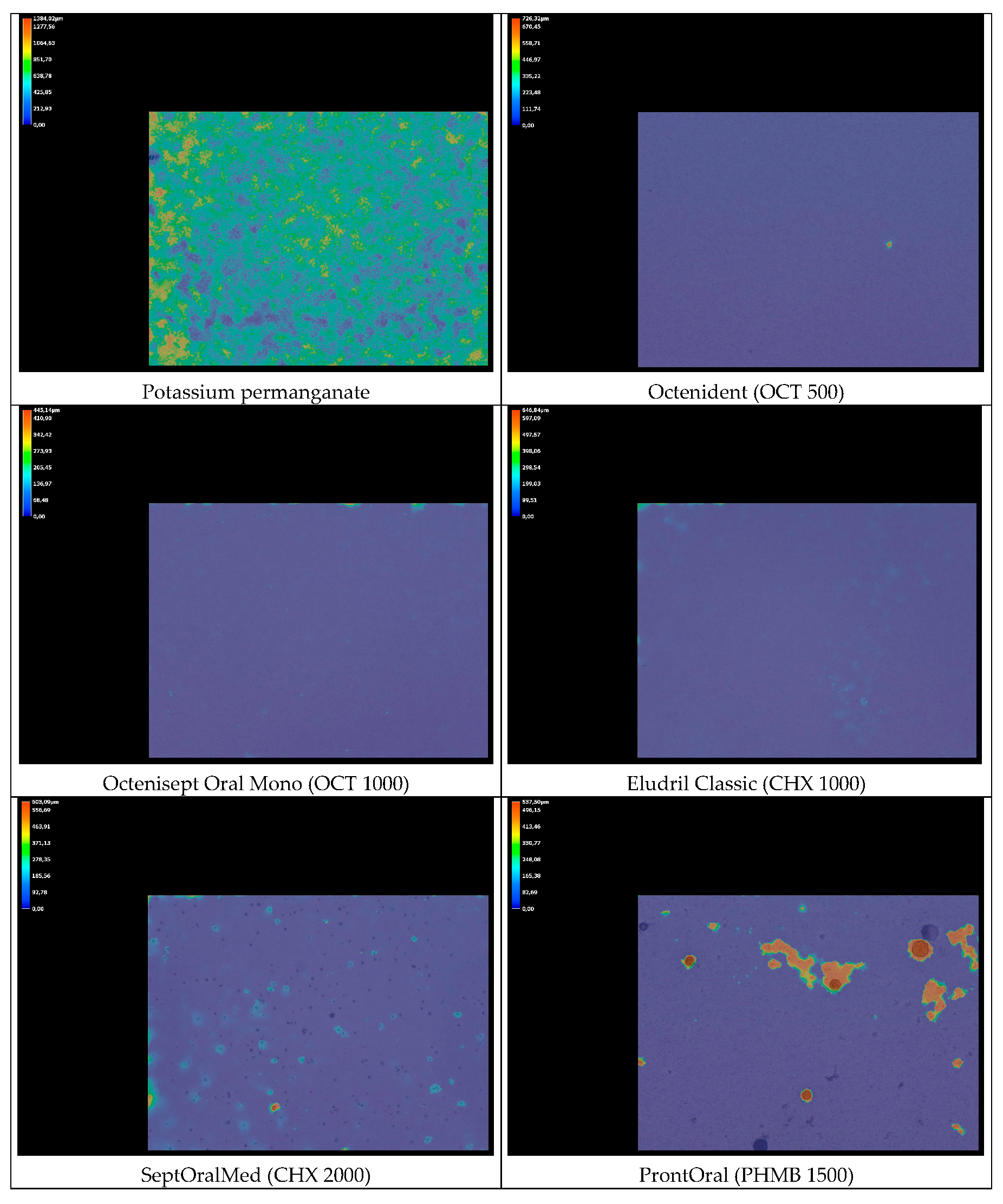

2.6.2. Biofilm Thickness Analysis

2.6.3. LIVE/DEAD Biofilm Viability

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Antimicrobial Activity (MIC, MBC and CEMIC)

3.2. Cell Viability and Antibiofilm Activity

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carvajal, P.; Gómez, M.; Gomes, S.; Costa, R.; Toledo, A.; Solanes, F.; Romanelli, H.; Oppermann, R.; Rösing, C.; Gamonal, J. Prevalence, Severity, and Risk Indicators of Gingival Inflammation in a Multi-Center Study on South American Adults: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2016, 24, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gare, J.; Kanoute, A.; Orsini, G.; Gonçalves, L.S.; Ali Alshehri, F.; Bourgeois, D.; Carrouel, F. Prevalence, Severity of Extension, and Risk Factors of Gingivitis in a 3-Month Pregnant Population: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, G.; Vargas, M.A.; Castillo, J.; Serrano, J.J.; Ramirez, G.M.; Humberto Viales, J.; Benitez, C.G.; Murillo, G.; Vargas, M.A.; Castillo, J.; et al. Prevalence and Severity of Plaque-Induced Gingivitis in Three Latin American Cities: Mexico City-Mexico, Great Metropolitan Area-Costa Rica and Bogota-Colombia. Odovtos Int. J. Dent. Sci. 2018, 20, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germen, M.; Baser, U.; Lacin, C.C.; Fıratlı, E.; İşsever, H.; Yalcin, F. Periodontitis Prevalence, Severity, and Risk Factors: A Comparison of the AAP/CDC Case Definition and the EFP/AAP Classification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, D.; Carvalho, R.; Machado, V.; Chambrone, L.; Mendes, J.J.; Botelho, J. Prevalence of Periodontitis in Dentate People between 2011 and 2020: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Studies. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 604–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socransky, S.S.; Haffajee, A.D.; Cugini, M.A.; Smith, C.; Kent, R.L., Jr. Microbial Complexes in Subgingival Plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1998, 25, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksijević, L.H.; Aleksijević, M.; Škrlec, I.; Šram, M.; Šram, M.; Talapko, J. Porphyromonas gingivalis Virulence Factors and Clinical Significance in Periodontal Disease and Coronary Artery Diseases. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, G.; Sela, M.N. Coaggregation of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum PK 1594 Is Mediated by Capsular Polysaccharide and Lipopolysaccharide. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 256, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, Y.; Nagano, K. Porphyromonas gingivalis FimA and Mfa1 Fimbriae: Current Insights on Localization, Function, Biogenesis, and Genotype. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2021, 57, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Han, N.; Du, J.; Guo, L.; Luo, Z.; Liu, Y. Pathogenesis of Important Virulence Factors of Porphyromonas gingivalis via Toll-Like Receptors. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Liang, S. Roles of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Its Virulence Factors in Periodontitis. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2020, 120, 45–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widziolek, M.; Mieszkowska, A.; Marcinkowska, M.; Salamaga, B.; Folkert, J.; Rakus, K.; Chadzinska, M.; Potempa, J.; Stafford, G.P.; Prajsnar, T.K.; et al. Gingipains Protect Porphyromonas gingivalis from Macrophage-Mediated Phagocytic Clearance. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hočevar, K.; Potempa, J.; Turk, B. Host Cell-Surface Proteins as Substrates of Gingipains, the Main Proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Biol. Chem. 2018, 399, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Long, W.; Yin, Y.; Tan, B.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Ge, S. Outer Membrane Vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis: Recent Advances in Pathogenicity and Associated Mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1555868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrendik, M. Rheumatoid Arthritis Is an Autoimmune Disease Caused by Periodontal Pathogens. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2013, 6, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhi, L.; Sakalihasan, N.; Okroglic, A.G.; Labropoulos, N.; Seidel, L.; Albert, A.; Teughels, W.; Defraigne, J.-O.; Lambert, F. Further Evidence on the Relationship between Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Periodontitis: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Periodontol. 2020, 91, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendonça, G.V.; Junior, C.C.; Feitosa, A.C.R.; de Mendonça, B.F.S.; Pimassoni, L.H.S. Periodontitis and Non-Communicable Diseases in a Brazilian Population, a Cross-Sectional Study, Vila Velha-ES, Brazil. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2024, 15, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halboub, E.; Al-Maswary, A.; Mashyakhy, M.; Al-Qadhi, G.; Al-Maweri, S.A.; Ba-Hattab, R.; Abdulrab, S. The Potential Association Between Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Apical Periodontitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Endod. J. 2024, 9, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knop-Chodyła, K.; Kochanowska-Mazurek, A.; Piasecka, Z.; Głaz, A.; Wesołek-Bielaska, E.W.; Syty, K.; Forma, A.; Baj, J. Oral Microbiota and the Risk of Gastrointestinal Cancers—A Narrative Literature Review. Pathogens 2024, 13, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, N.V.; Trivedi, S.; Vachhani, K.S.; Brahmbhatt, N.; Shah, S.; Patel, N.; Gupta, D.; Periasamy, R. Association between Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight and Maternal Chronic Periodontitis: A Hospital-Based Case-Control Study. Dent. Med. Probl. 2023, 60, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology. Treatment of Plaque-Induced Gingivitis, Chronic Periodontitis, and Other Clinical Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2001, 72, 1790–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiley, C.J.; Tracy, S.L.; Abt, E.; Michalowicz, B.S.; John, M.T.; Gunsolley, J.; Cobb, C.M.; Rossmann, J.; Harrel, S.K.; Forrest, J.L.; et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline on the Nonsurgical Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis by Means of Scaling and Root Planing with or without Adjuncts. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2015, 146, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Kotsakis, G.A.; Chu, H. Network Meta-Analysis of Studies Included in the Clinical Practice Guideline on the Nonsurgical Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, L.; Lyra, P.; Rodrigues, J.; Viana, J.; Mendes, J.J.; Barroso, H. Revisiting Oral Antiseptics, Microorganism Targets and Effectiveness. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanauskaite, E.; Machiulskiene, V. Antiseptics as Adjuncts to Scaling and Root Planing in the Treatment of Periodontitis: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.-S.; Huang, X.-Q.; Griffin, B.; Bergeron, B.R.; Pashley, D.H.; Niu, L.-N.; Tay, F.R. Primum Non Nocere—The Effects of Sodium Hypochlorite on Dentin as Used in Endodontics. Acta Biomater. 2017, 61, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, H.K.R.; Mrozikiewicz-Rakowska, B.; Pinto, D.S.; Stuermer, E.K.; Matiasek, J.; Sander, J.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.L.; Ousey, K.; Assadian, O.; Kim, P.J.; et al. Use of Wound Antiseptics in Practice. International Consensus Document. Wounds Int. 2023, 1–27. Available online: www.woundsinternational.com (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Kramer, A.; Dissemond, J.; Kim, S.; Willy, C.; Mayer, D.; Papke, R.; Tuchmann, F.; Assadian, O. Consensus on Wound Antisepsis: Update 2018. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 31, 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincses, A.; Ghazal, T.S.A.; Hohmann, J. Synergistic Effect of Phenylpropanoids and Flavonoids with Antibiotics against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacterial Strains. Pharm. Biol. 2024, 62, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpiński, T.M.; Korbecka-Paczkowska, M.; Stasiewicz, M.; Mrozikiewicz, A.E.; Włodkowic, D.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Activity of Antiseptics Against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Its Adaptation Potential. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korbecka-Paczkowska, M.; Karpiński, T.M. In Vitro Assessment of Antifungal and Antibiofilm Efficacy of Commercial Mouthwashes against Candida albicans. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, T.M. Biofilm Thickness Analyzer: A Program for Measuring Biofilm Thickness in 3D Images from a Keyence VHX-S770E Digital Microscope. 2025. Available online: https://Github.Com/Tkarpin1/BiofilmThicknessAnalyzer (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Oncu, A.; Celikten, B.; Aydın, B.; Amasya, G.; Tuncay, E.; Eskiler, G.G.; Açık, L.; Sevimay, F.S. Antibacterial Efficacy of Silver Nanoparticles, Sodium Hypochlorite, Chlorhexidine, and Hypochlorous Acid on Dentinal Surfaces Infected with Enterococcus faecalis. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2024, 87, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, B.; Tymińska, J.; Szymczyk-Ziółkowska, P.; Chodaczek, G.; Migdał, P.; Czajkowska, J.; Junka, A. In Vitro Activity of Octenidine Dihydrochloride-Containing Lozenges against Biofilm-Forming Pathogens of Oral Cavity and Throat. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verspecht, T.; Rodriguez Herrero, E.; Khodaparast, L.; Khodaparast, L.; Boon, N.; Bernaerts, K.; Quirynen, M.; Teughels, W. Development of Antiseptic Adaptation and Cross-Adapatation in Selected Oral Pathogens in Vitro. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoux, E.; Lagha, A.B.; Gauthier, P.; Grenier, D. Antimicrobial Activities of Natural Plant Compounds against Endodontic Pathogens and Biocompatibility with Human Gingival Fibroblasts. Arch. Oral Biol. 2020, 116, 104734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, M.M.; Bhat, K.G.; Joshi, V.M. Comparative Evaluation of the Efficacy of a Herbal Mouthwash and Chlorhexidine Mouthwash on Select Periodontal Pathogens: An In Vitro and Ex Vivo Study. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2017, 21, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo-Castaño, C.; Vásquez, D.; Bolaños, G.; Contreras, A. Strong Antimicrobial Activity of Collinin and Isocollinin against Periodontal and Superinfectant Pathogens In Vitro. Anaerobe 2020, 62, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. Effects of Chlorhexidine Digluconate and Hydrogen Peroxide on Porphyromonas gingivalis Hemin Binding and Coaggregation with Oral Streptococci. J. Oral Sci. 2001, 43, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akca, A.E.; Akca, G.; Topçu, F.T.; Macit, E.; Pikdöken, L.; Özgen, I.Ş. The Comparative Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Effect of Propolis with Chlorhexidine against Oral Pathogens: An In Vitro Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 3627463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bercy, P.; Lasserre, J. Susceptibility to Various Oral Antiseptics of Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 within a Biofilm. Adv. Ther. 2007, 24, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, J.P.; Garcia-Godoy, F. In Vitro Comparison of Commercial Oral Rinses on Bacterial Adhesion and Their Detachment from Biofilm Formed on Hydroxyapatite Disks. Oral. Health Prev. Dent. 2014, 12, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, Z.; Ucan, U.S.; Sakmanoglu, A. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Effects of Boron on Different Bacteria. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016, 173, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.A.V.; Nguyen, M.D. Subgingival 0.75% Boric Acid vs 1% Povidone-Iodine Adjunctive to Subgingival Instrumentation in Stage II and III Periodontitis-A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisodiya, M.; Ahmed, S.; Sengupta, R.; Priyanka; Saha, A.K.; Verma, G. A Comparative Assessment of Pomegranate Extract, Sodium Hypochlorite, Chlorhexidine, Myrrh (Commiphora Molmol), Tulsi Extract against Enterococcus faecalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Staphylococci epidermidis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2021, 25, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, D.A.; Pratten, J.; Wilson, M.; Gulabivala, K. An In Vitro Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Efficacy of Irrigants on Biofilms of Root Canal Isolates. Int. Endod. J. 2001, 34, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.T.S.; Cheung, G.S.P. Extension of Bactericidal Effect of Sodium Hypochlorite into Dentinal Tubules. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpiński, T.M. Adaptation Index (KAI)—A New Indicator of Adaptation and Potential Antimicrobial Resistance. Herba Pol. 2024, 70, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, T.M.; Korbecka-Paczkowska, M.; Ożarowski, M.; Włodkowic, D.; Wyganowska, M.L.; Seremak-Mrozikiewicz, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Adaptation to Sodium Hypochlorite and Potassium Permanganate May Lead to Their Ineffectiveness Against Candida albicans. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, D.; Lwin, H.Y.; Aoki-Nonaka, Y.; Matsugishi-Nasu, A.; Minato, Y.; Warita, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Tabeta, K. Ferulic Acid Suppresses Porphyromonas gingivalis Biofilm Formation via the Inhibition of Autoinducer-2 Production and Receptor Activity. Arch. Oral Biol. 2025, 178, 106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Heupt, L.K.; Vierengel, N.; Groß, J.; Opatz, T.; Deschner, J.; von Loewenich, F.D. Antimicrobial Activity of Eucalyptus globulus, Azadirachta indica, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Rheum palmatum Extracts and Rhein against Porphyromonas gingivalis. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-H.; Shin, S.-J.; Tae, H.-J.; Oh, S.-H.; Bae, J.-M. Effects of Colocasia antiquorum Var. Esculenta extract In Vitro and In Vivo against Periodontal Disease. Medicina 2021, 57, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dydak, K.; Junka, A.; Dydak, A.; Brożyna, M.; Paleczny, J.; Fijalkowski, K.; Kubielas, G.; Aniołek, O.; Bartoszewicz, M. In Vitro Efficacy of Bacterial Cellulose Dressings Chemisorbed with Antiseptics against Biofilm Formed by Pathogens Isolated from Chronic Wounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleczny, J.; Junka, A.; Brożyna, M.; Dydak, K.; Oleksy-Wawrzyniak, M.; Ciecholewska-Juśko, D.; Dziedzic, E.; Bartoszewicz, M. The High Impact of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Culture Medium on In Vitro Outcomes of Antimicrobial Activity of Wound Antiseptics and Antibiotic. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paleczny, J.; Junka, A.F.; Krzyżek, P.; Czajkowska, J.; Kramer, A.; Benkhai, H.; Żyfka-Zagrodzińska, E.; Bartoszewicz, M. Comparison of Antibiofilm Activity of Low-Concentrated Hypochlorites vs Polyhexanide-Containing Antiseptic. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1119188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoszewicz, M.; Junka, A.; Dalkowski, P.; Sopata, M. Evaluation of efficacy of antiseptics against biofilmic and planktonic forms of Enterococcus faecalis causing local infection. Forum Zakażeń 2017, 8, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkowski, P.; Bartoszewicz, M.; Junka, A.; Sopata, M. Evaluation of efficacy of antiseptics against biofilmic and planktonic forms of Klebsiella pneumoniae causing local infections. Forum Zakażeń 2017, 8, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, F.S.F.; Garcia, L.M.; Moraes, T.d.S.; Casemiro, L.A.; Alcântara, C.B.d.; Ambrósio, S.R.; Veneziani, R.C.S.; Miranda, M.L.D.; Martins, C.H.G. Antibacterial Activity of Salvia officinalis L. against Periodontopathogens: An In Vitro Study. Anaerobe 2020, 63, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, A.C.R. Anaerobic Culture to Detect Periodontal and Caries Pathogens. J. Oral Biosci. 2015, 57, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E.; Boyanova, L.; Justesen, U.S. ESCMID Study Group of Anaerobic Infections. How to Isolate, Identify and Determine Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Anaerobic Bacteria in Routine Laboratories. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, K.; Rodríguez-Hernández, A.-P.; Martínez-Hernández, M. Insights Into the Mechanism of Action of Chlorhexidine on Porphyromonas gingivalis. Int. J. Dent. 2025, 2025, 1492069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, R.; Alvitez-Temoche, D.; Chiong, L.; Silva, H.; Mauricio, F.; Mayta-Tovalino, F. Antibacterial Efficacy of Matricaria Recutita Essential Oil against Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella Intermedia: In Vitro Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2023, 24, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozza, F.L.; Molgatini, S.L.; Pérez, S.B.; Tejerina, D.P.; Pérez Tito, R.I.; Kaplan, A.E. Antimicrobial Effect in Vitro of Chlorhexidine and Calcium Hydroxide Impregnated Gutta-Percha Points. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 2005, 18, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halkai, K.R.; Mudda, J.A.; Shivanna, V.; Rathod, V.; Halkai, R.S. Evaluation of Antibacterial Efficacy of Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles Derived from Fungi against Endo-Perio Pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis, Bacillus pumilus, and Enterococcus faecalis. J. Conserv. Dent. 2017, 20, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pure Antiseptics | Used Concentration (µg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Octenidine dihydrochloride (OCT) (Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany) | 1000 |

| Chlorhexidine digluconate (CHX) (Sigma-Aldrich, Poznań, Poland) | 1000 |

| Polyaminopropyl biguanide (Polihexanide, PHMB) (Arxada AG, Basel, Switzerland) | 1000 |

| Boric acid (BA) (Herbapol, Poznań, Poland) | 30,000 |

| Ethacridine lactate (ET) (Herbapol, Poznań, Poland) | 1000 |

| Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) (Cerkamed, Stalowa Wola, Poland) | 100 |

| Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Hasco-Lek S.A., Wrocław, Poland) | 30,000 |

| Potassium permanganate (KMnO4) (Hasco-Lek S.A., Wrocław, Poland) | 10,000 |

| Mouthwashes | Active Compound and Its Concentration (µg/mL) |

| Octenident® (Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany) | OCT 500 |

| Octenisept Oral Mono® (Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany) | OCT 1000 |

| Eludril Classic® (Pierre Fabre, Cahors, France) | CHX 1000 |

| SeptOralMed® (Avec Pharma, Wrocław, Poland) | CHX 2000 |

| ProntOral® (B Braun, Melsungen, Germany) | PHMB 1500 |

| Antiseptic/Mouthwash | MICs of the Product [%] | MICs/MBCs of Active Compound [µg/mL] | CEMIC | MBC/MIC Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octenidine dihydrochloride (OCT) 1000 µg/mL | 0.024–0.049 | 0.24–0.49 | 0.00024–0.00049 | 1 |

| Chlorhexidine digluconate (CHX) 1000 µg/mL | 0.098–0.195 | 0.98–1.95 | 0.00098–0.00195 | 1 |

| Polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) 1000 µg/mL | 0.781–1.56 | 7.81–15.63 | 0.00781–0.0156 | 1 |

| Boric acid (BA) 30,000 µg/mL | 12.5 | 3750 | 0.125 | 1 |

| Ethacridine lactate (ET) 1000 µg/mL | 6.25 | 62.5 | 0.00625 | 1 |

| Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) 30,000 µg/mL | 1.56 | 470 | 0.0157 | 1 |

| Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) 200 µg/mL | 100 | 100/200 | 1 | 2 |

| Potassium permanganate (KMnO4) 10,000 µg/mL | 100 | 10,000 | 1 | 1 |

| Octenident® (OCT 800 µg/mL) | 0.098 | 0.78 | 0.00098 | 1 |

| Octenisept Oral Mono® (OCT 1000 µg/mL) | 0.024–0.049 | 0.24–0.49 | 0.00024–0.00049 | 1 |

| Eludril Classic® (CHX 1000 µg/mL) | 0.049–0.098 | 0.49–0.98 | 0.00049–0.00098 | 1 |

| SeptOralMed® (CHX 2000 µg/mL) | 0.024 | 0.49 | 0.000245 | 1 |

| ProntOral® (PHMB 1500 µg/mL) | 0.781 | 11.72 | 0.0078 | 1 |

| Antiseptic | Absorbance After 1 h Exposure Time |

|---|---|

| Control | 0.841 ± 0.033 |

| OCT 1000 µg/mL | 0.172 ± 0.033 *** |

| CHX 1000 µg/mL | 0.196 ± 0.028 *** |

| PHMB 1000 µg/mL | 0.260 ± 0.036 *** |

| BA 30,000 µg/mL | 0.708 ± 0.033 ns |

| ET 1000 µg/mL | 0.553 ± 0.031 ** |

| H2O2 30,000 µg/mL | 0.405 ± 0.053 *** |

| NaOCl 200 µg/mL | 0.766 ± 0.042 ns |

| KMnO4 10,000 µg/mL | 0.790 ± 0.063 ns |

| Antiseptic | Clinical Efficiency of MIC (CEMIC) | Significant Reduction in Biofilm | Clinical Utility Against P. gingivalis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass | Viability | Thickness | |||

| Octenidine dihydrochloride (OCT) 1000 µg/mL | Excellent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chlorhexidine digluconate (CHX) 1000 µg/mL | Excellent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) 1000 µg/mL | Excellent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ethacridine lactate (ET) 1000 µg/mL | Excellent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) 30,000 µg/mL | Excellent | Yes | Yes | No | Partially |

| Boric acid (BA) 30,000 µg/mL | Moderate | No | Yes | No | Partially |

| Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) 200 µg/mL | Poor | No | Yes | No | No |

| Potassium permanganate (KMnO4) 10,000 µg/mL | Poor | No | No | No | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korbecka-Paczkowska, M.; Karpiński, T.M.; Ożarowski, M. Comparative Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity of Antiseptics and Commercial Mouthwashes Against Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8909. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248909

Korbecka-Paczkowska M, Karpiński TM, Ożarowski M. Comparative Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity of Antiseptics and Commercial Mouthwashes Against Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8909. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248909

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorbecka-Paczkowska, Marzena, Tomasz M. Karpiński, and Marcin Ożarowski. 2025. "Comparative Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity of Antiseptics and Commercial Mouthwashes Against Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8909. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248909

APA StyleKorbecka-Paczkowska, M., Karpiński, T. M., & Ożarowski, M. (2025). Comparative Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity of Antiseptics and Commercial Mouthwashes Against Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8909. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248909