Oral Hygiene Practices of Hospitalized Patients in Public and Private Hospitals in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

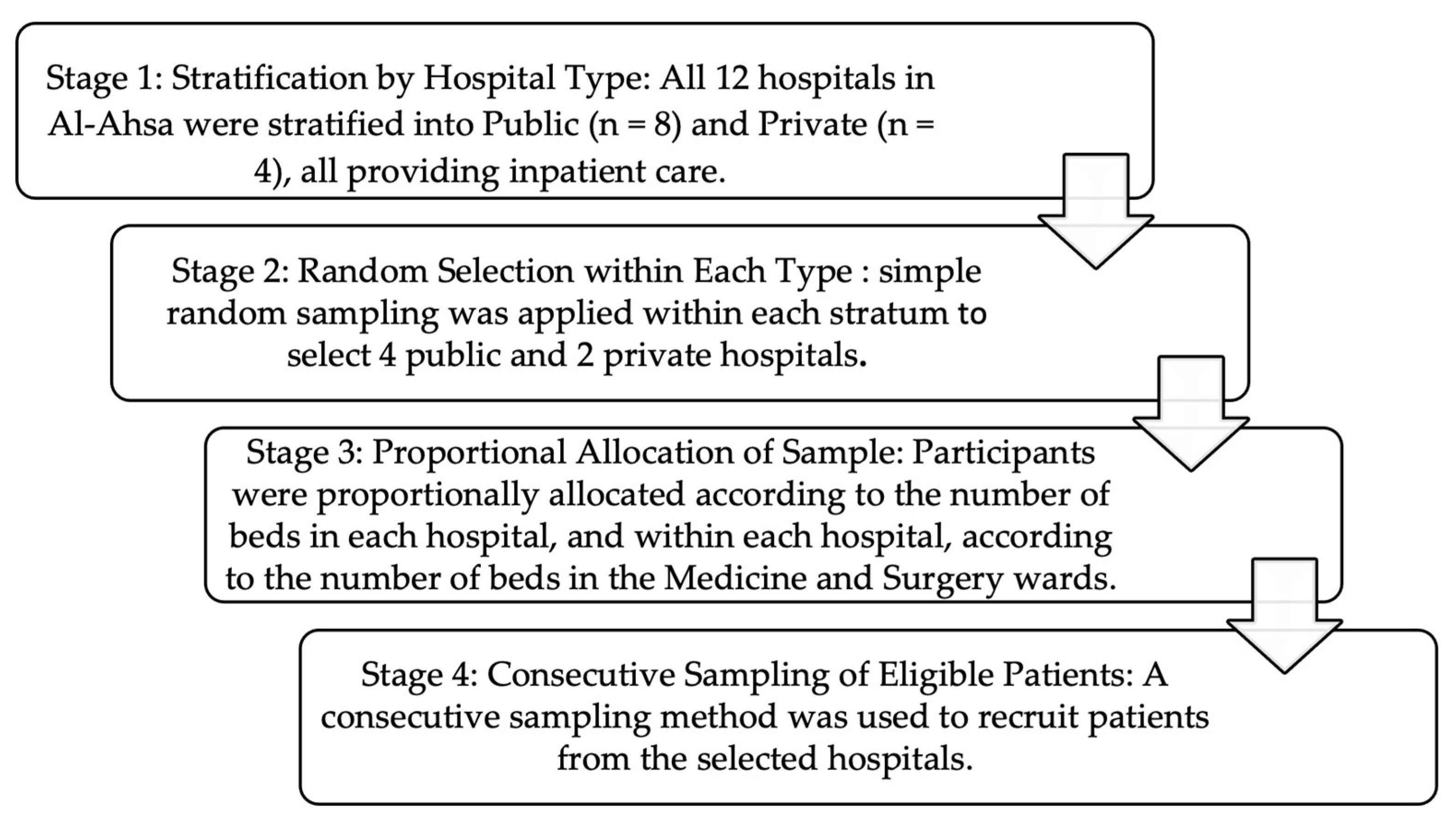

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

2.2. Study Tool

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Hospitalization Profile

3.2. Oral Hygiene Practices Before and During Hospitalization

3.3. Availability of Oral Hygiene Supplies and Oral Care Services

3.4. Satisfaction with Care and Oral Health Issues

3.5. Comparison of Oral Hygiene Practices and Support Services Between Public and Private Hospitals

3.6. Predictors of Toothbrushing Behavior Among Hospitalized Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| n | Required sample size |

| N | Total population size |

| Z | Z-value corresponding to the desired confidence level (1.96 for 95%) |

| p | Estimated population proportion |

| MOE | Margin of error |

References

- Hapsari, R.N.W.; Mamun, A.A. Oral health: Essential for overall well-being and quality of life. Health Dyn. 2024, 1, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noort, H.H.J.; Witteman, B.J.M.; den Hertog-Voortman, R.; Everaars, B.; Vermeulen, H.; Huisman-de Waal, G. How oral care is delivered in hospitalised patients: A mixed-methods study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 1991–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, S.; Gholap, S.; Parmar, D.; Bhatt, N. Effectiveness of a standard oral care plan during hospitalization in patients with acquired brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 714167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winning, L.; Lundy, F.T.; Blackwood, B.; McAuley, D.F. Oral health care for the critically ill: A narrative review. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, M.B.; Neuburger, M.J.; Magill, S.S.; Perkins, K.M. Oral care in nonventilated hospitalized patients. Am. J. Infect. Control 2025, 53, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livesey, A.; Quarton, S.; Pittaway, H.; Adiga, A.; Grudzinska, F.; Dosanjh, D.; Parekh, D. Practices to prevent non-ventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia: A narrative review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2024, 151, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupi, S.M.; Pascadopoli, M.; Maiorani, C.; Preda, C.; Trapani, B.; Chiesa, A.; Esposito, F.; Scribante, A.; Butera, A. Oral hygiene practice among hospitalized patients: An assessment by dental hygiene students. Healthcare 2022, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viebranz, S.; Dederichs, M.; Kwetkat, A.; Schüler, I.M. Effectiveness of individual oral health care training in geriatric wards. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mubarak, S.; Al-Nowaiser, A.; Rass, M.A.; Alsuwyed, A.; Al-Suwyed, A. Oral health status and oral health-related quality of life among hospitalized and nonhospitalized geriatric patients in Saudi Arabia. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2017, 18, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rababah, D.M.A.; Nassani, M.Z.; Baker, O.G.; Alhelih, E.M.; Almomani, S.A.; Rastam, S. Attitudes and practices of nurses toward oral care of hospitalized patients—Riyadh. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Orem, D.E. Nursing: Concepts of Practice, 6th ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano, K.K.; Penoyer, D.; Middleton, A.; Baker, D. Oral care as prevention for nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia: A four-unit cluster randomized study. Am. J. Nurs. 2021, 121, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehan, P.E.; Browne, K.; Matterson, G.; Cheng, A.C.; Dawson, S.; Graves, N.; Johnson, D.; Kiernan, M.; Madhuvu, A.; Marshall, C.; et al. Oral care practices and HAP prevention: A National survey of Australian nurses. Infect. Dis. Health. 2024, 29, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, I.L.; Halberg, N.; Jensen, P.S. “Why doesn’t anyone ask me?”: Patients’ experiences of oral care in acute orthopaedics. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2023, 37, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Ministry of Health. Saudi Vision 2030: Health Sector Transformation Program; Saudi Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Ministry of Health. Al-Ahsa Health Cluster; Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Aljauid, A.S.; Al-Otaibi, A.O.; Aldawood, M.M.; Mohamed, R.N.; Basha, S.; Thomali, Y.A. Oral health behavior of medical, dental, and pharmacology students in Taif University. J. Adv. Oral Res. 2020, 11, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V. Some practical guidelines for effective sample size determination. Am. Stat. 2001, 55, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, B.; Alarifi, H.; Alharbi, G.; Alanazi, A.; Alshammari, N.; Almutairi, W.; Alshalawi, I. Oral health status among medically compromised children within Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A case-control study. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 5, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Miyabe, S.; Ishibashi, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Goto, M.; Hasegawa, S.; Miyachi, H.; Fujita, K.; Nagao, T. Oral hygiene status and related factors in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 20, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lages, V.A.; Dutra, T.T.B.; Lima, A.N.D.A.; Mendes, R.F.; Prado Júnior, R.R. The impact of hospitalization on periodontal health status: An observational study. RGO Rev. Gaúcha Odontol. 2017, 65, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsaro, A.; Leung, A.; Mikulic, T.; Petrovic, D. The role of oral health literacy and socioeconomic factors in oral hygiene behaviors among adults. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Hawsawi, A.M.; AlHarbi, H.A.; Alzahrani, F.A.; Alghamdi, M.A.; Alotaibi, R.H.; Alzahrani, M.A. Socioeconomic disparities and health behaviors in Saudi adults: Findings from the 2022 National Health Survey. Saudi J. Public Health 2022, 7, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Ministry of Health. Health Statistics Yearbook 2024; Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, S.; Kolyaei, E.; Karimi, P.; Rahmani, K. Supervised oral health care protocol for VAP prevention in ICUs: Double-blind multicenter RCT. Infect. Prev. Pract. 2023, 5, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, S. Family involvement in oral hygiene of hospitalized patients: A multicenter survey from China. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 534. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yao, L.; Yang, X.; Huang, M.; Zhang, B.; Yu, T.; Tang, Y. ICU nursing assistants’ perceptions and barriers to oral care: A qualitative study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 39–79. [Google Scholar]

- Goryawala, S.N.; Chavda, P.; Udhani, S.; Pathak, N.V.; Pathak, S.; Ojha, R. A survey on oral hygiene methods practiced by patients at a tertiary care hospital in Central Gujarat. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2016, 6, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneyama, T.; Yoshida, M.; Ohrui, T.; Mukaiyama, H.; Okamoto, H.; Hoshiba, K.; Ihara, S.; Yanagisawa, S.; Ariumi, S.; Morita, T.; et al. Oral care reduces pneumonia in older patients in nursing homes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monica, F.P.E.; Aloweni, F.; Yuh, A.S.; Ayob, E.B.M.; Ahmad, N.B.; Lan, C.J.; Lian, H.A.; Chee, L.L.; Ayre, T.C. Preparation and response to COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore: A case report. Infect. Dis. Health 2020, 25, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.; Paunovic, J.; Hunter, S.C. More than a mouth to clean: Case studies of oral health care in an Australian hospital. Gerodontology 2024, 41, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, M.S.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Alshehri, S.A.; Alotaibi, R.H. Oral health literacy and preventive dental behaviors among Saudi adults. Saudi Dent. J. 2021, 33, 254–261. [Google Scholar]

- Al Qahtani, N.A.; Al-Mutairi, H.A.; Alshahrani, A.M.; Alshehri, M.A. Predictors of oral hygiene practices and preventive dental visits among adults in the Gulf region. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 651. [Google Scholar]

| Socio-Demographic Data | No | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| 18–29 | 37 | (21.5) |

| 30–39 | 28 | (16.4) |

| 40–49 | 34 | (19.9) |

| 50–59 | 23 | (13.5) |

| 60–69 | 29 | (17.0) |

| 70+ | 20 | (11.7) |

| Mean ± SD (95% CI) | 46.9 ± 18.7 (44.1–49.7) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 100 | (58.5) |

| Female | 71 | (41.5) |

| Nationality | ||

| Saudi | 141 | (82.5) |

| Non-Saudi | 30 | (17.5) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 41 | (24.0) |

| Married | 109 | (63.7) |

| Divorced/widow | 21 | (12.3) |

| Place of Residency | ||

| Al-Hofuf | 68 | (39.8) |

| Al-Mubarraz | 42 | (24.6) |

| Al-Oyun | 5 | (2.9) |

| Village | 56 | (32.7) |

| Educational level | ||

| Non-educated | 23 | (13.5) |

| Below secondary education | 49 | (28.7) |

| Secondary/diploma | 57 | (33.3) |

| Bachelor degree/above | 42 | (24.6) |

| Employment | ||

| Unemployed | 77 | (45.0) |

| Governmental employee | 14 | (8.2) |

| Self-employed | 5 | (2.9) |

| Private sector employee | 48 | (28.1) |

| Retired | 27 | (15.8) |

| Monthly income | ||

| <5000 SR | 67 | (39.2) |

| 5000–9999 SR | 61 | (35.7) |

| 10,000–15,000 SR | 34 | (19.9) |

| >15,000 SR | 9 | (5.3) |

| Medical and Hospitalization | No | % |

|---|---|---|

| Type of hospital you are currently admitted to | ||

| Public hospital | 80 | (46.8) |

| Private hospital | 91 | (53.2) |

| Ward you are currently admitted to | ||

| Medicine | 88 | (51.5) |

| Surgery | 83 | (48.5) |

| Length of Current Hospital Stay (in days) | ||

| 3–7 days | 101 | (59.1) |

| 7–14 days | 45 | (26.3) |

| >14 days | 25 | (14.6) |

| The cause of your hospitalization | ||

| Acute illness | 104 | (60.8) |

| Chronic condition | 67 | (39.2) |

| Do you have any systemic diseases? | ||

| No systemic diseases | 57 | (33.3) |

| One systemic disease | 63 | (36.8) |

| More than one systemic disease | 51 | (29.8) |

| How are you covering your medical expenses as a hospitalized patient? | ||

| Entitled to free healthcare (complete coverage by government) | 72 | (42.1) |

| Insurance | 98 | (57.3) |

| Out-of-pocket expenses | 1 | (0.6) |

| Have you ever been hospitalized before? | ||

| Yes | 127 | (74.3) |

| No | 44 | (25.7) |

| When was your last hospitalization? | ||

| Within the last 3 months | 49 | (38.6) |

| Within the last 6 months | 21 | (16.5) |

| Within the last 1 year | 11 | (8.7) |

| Over 1 year ago | 46 | (36.2) |

| How many times of previous hospitalizations | ||

| Median (Range) | 3 (1–67) | |

| Items | All No (%) | Public No (%) | Private No (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Hospitalization | ||||

| How often do you brush your teeth? | ||||

| I don’t brush my teeth | 17 (9.9) | 9 (11.2) | 8 (8.8) | 0.940 |

| Once a week | 12 (7.0) | 5 (6.2) | 7 (7.7) | |

| Twice a week | 7 (4.1) | 4 (5.0) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Every other day (alternating days) | 16 (9.4) | 7 (8.8) | 9 (9.9) | |

| Once a day | 50 (29.2) | 21 (26.2) | 29 (31.9) | |

| Twice a day | 55 (32.2) | 26 (32.6) | 29 (31.9) | |

| More than twice a day | 14 (8.2) | 8 (10.0) | 6 (6.6) | |

| Use of mouthwash | 0.700 | |||

| Yes | 30 (17.5) | 15 (18.8) | 15 (16.5) | |

| No | 141 (82.5) | 65 (81.2) | 76 (83.5) | |

| Use of dental floss | 0.360 | |||

| Yes | 19 (11.1) | 7 (8.8) | 12 (13.2) | |

| No | 152 (88.9) | 73 (91.2) | 79 (86.8) | |

| Use of miswak | 0.004 * | |||

| Yes | 7 (4.1) | 7 (8.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 164 (95.9) | 73 (91.2) | 91 (100.0) | |

| During Hospitalization | ||||

| Have your teeth been cleaned since admission? | 0.520 | |||

| Yes | 62 (36.3) | 27 (33.8) | 35 (38.5) | |

| No | 109 (63.7) | 53 (66.2) | 56 (61.5) | |

| When were your teeth first cleaned after admission? | 0.350 | |||

| From the first day | 21 (33.9) | 6 (22.2) | 15 (42.9) | |

| Second day | 15 (24.2) | 8 (29.6) | 7 (20.0) | |

| Third day or later | 26 (41.9) | 13 (48.1) | 13 (37.1) | |

| Reasons teeth not cleaned from first day a (n = 41) | <0.001 * | |||

| No toothbrush available | 20 (48.8) | 17 (81.0) | 3 (15.0) | |

| No oral hygiene instructions | 5 (12.2) | 4 (19.0) | 1 (5.0) | |

| Medical condition prevented brushing | 16 (39.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (80.0) | |

| Ability to clean teeth independently | 0.010 * | |||

| Yes | 75 (43.9) | 26 (32.5) | 49 (53.8) | |

| No | 96 (56.1) | 54 (67.5) | 42 (46.2) | |

| If unable, who assists? | 0.160 ^ | |||

| Nurse | 3 (3.1) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Family member | 17 (17.7) | 6 (11.1) | 11 (26.2) | |

| No assistance | 76 (79.2) | 45 (85.2) | 30 (71.4) | |

| How often do you brush during stay? | 0.310 ^ | |||

| I don’t brush my teeth | 115 (67.3) | 58 (72.5) | 57 (62.6) | |

| Once a week | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Twice a week | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Every other day | 3 (1.8) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Once a day | 26 (15.2) | 11 (13.8) | 15 (16.5) | |

| Twice a day | 22 (12.9) | 6 (7.5) | 16 (17.6) | |

| More than twice a day | 3 (1.8) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Use of mouthwash | 0.250 ^ | |||

| Yes | 4 (2.3) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.1) | |

| No | 167 (97.7) | 77 (96.3) | 90 (98.9) | |

| Use of dental floss | 0.350 ^ | |||

| Yes | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| No | 170 (99.4) | 80 (100.0) | 90 (98.9) | |

| Use of miswak | 0.550 ^ | |||

| Yes | 5 (2.9) | 3 (3.8) | 2 (2.2) | |

| No | 166 (97.1) | 77 (96.3) | 89 (97.8) |

| Service | All No (%) | Public No (%) | Private No (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did the hospital provide you with oral hygiene supplies (e.g., toothbrush, toothpaste, mouthwash) during your stay? | ||||

| Yes | 51(29.8) | 2 (2.5) | 49 (53.8) | |

| No | 116(67.8) | 77 (96.3) | 39 (42.9) | <0.001 * |

| Upon request | 4 (2.3) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (3.3) | |

| If not, did you bring your oral hygiene supplies? | ||||

| Yes | 36 (31.0) | 26 (32.5) | 10 (25.6) | 0.370 ^ |

| No | 80 (69.0) | 51 (67.5) | 29 (74.4) | |

| Do you think hospitals should provide oral hygiene supplies during patient stays? | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 3 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Neutral | 8 (4.7) | 1 (1.3) | 7 (7.7) | 0.060 |

| Agree | 27 (15.8) | 15 (18.8) | 12 (13.2) | |

| Strongly agree | 133(77.8) | 64 (80.0) | 69 (75.8) | |

| Did you receive any information about oral care during your hospital stay? | ||||

| No | 171(100) | 80 (100.0) | 91(100.0) | - |

| Did you receive an oral health assessment during your hospital stay? | ||||

| Yes | 16(9.4) | 4 (5.0) | 12 (13.2) | 0.070 ^ |

| No | 155(90.6) | 76 (95.0) | 79 (86.8) | |

| Who examined your mouth? | ||||

| Doctor | 16 (100) | 4 (25.0) | 12 (75.0) | - |

| When was the examination conducted? | ||||

| Upon admission | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (25.0) | |

| During hospital stay | 4 (25.0) | 1(6.3) | 3 (18.8) | 0.660 ^ |

| Before surgery or other major procedures | 8 (50.0) | 3 (18.8) | 5 (31.3) | |

| Based on your request | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) |

| Items | All No (%) | Public No (%) | Private No (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied were you with the oral health examination you received? | ||||

| Very satisfied | 1(6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Satisfied | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (25.0) | 0.760 |

| Neutral | 12(75.0) | 4 (100.0) | 8 (62.5) | |

| Very dissatisfied | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Did you experience any oral health issues during this hospital stay? | ||||

| Yes | 30(17.5) | 14 (17.5) | 16 (17.6) | 0.990 |

| No | 141(82.5) | 66 (82.5) | 75 (82.4) | |

| What are the oral health issues that you faced | ||||

| Dry mouth | 15 (50.0) | 6 (42.9) | 9 (56.3) | |

| Mouth sores | 9 (30.0) | 6 (42.9) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Difficulty swallowing | 6 (20.0) | 5 (35.7) | 1 (6.3) | |

| Gum swelling or inflammation | 5 (16.7) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (12.5) | 0.040 * |

| Bleeding gums | 4 (13.3) | 1 (7.1) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Tooth pain | 3 (10.0) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (6.3) | |

| Oral infections (e.g., thrush) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Fall down of the bridge | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) | |

| How were these issues addressed or treated by the hospital staff? | ||||

| Managed with basic intervention by the physician or medical staff | 9 (30.0) | 3 (21.4) | 6 (37.5) | |

| No concrete efforts were made to address the problem. | 18 (60.0) | 10 (71.4) | 8 (50.0) | 0.490 |

| Only an examination or consultation was performed by the physician or medical staff. | 3 (10.0) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (12.5) |

| Variable | All No (%) | Public No (%) | Private No (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have your teeth been cleaned since admission? | |||||

| Yes | 62 (36.3) | 27 (33.8) | 35 (38.5) | 0.815 (0.435–1.526) | |

| No | 109(63.7) | 53 (66.2) | 56 (61.5) | 0.520 | |

| Can you clean your teeth by yourself during hospital stay? | |||||

| Yes | 75 (43.9) | 26 (32.5) | 49 (53.8) | 0.413 (0.221–0.770) | 0.005 * |

| No | 96 (56.1) | 54 (67.5) | 42 (46.2) | ||

| Assistance with Oral Hygiene | |||||

| Received assistance | 3 (15.0) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) | 3.67 (0.27–49.29) | 0.310 |

| Did not receive assistance | 17 (85.0) | 6 (75.0) | 11 (91.7) | ||

| Tooth brushing | |||||

| Regular brushing | 51 (29.8) | 18 (22.5) | 33 (36.3) | 1.90 (0.94–3.86) | 0.070 |

| Infrequent/Never | 120 (70.2) | 62 (77.5) | 58 (63.7) | ||

| Do you use mouthwash? | |||||

| Yes | 4 (2.3) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| No | 167 (97.7) | 77 (96.3) | 90 (98.9) | 3.506 (0.357–34.403) | 0.250 |

| Do you use dental floss? | |||||

| Yes | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | ** | 0.350 |

| No | 170 (99.4) | 80 (100.0) | 90 (98.9) | ||

| Do you use miswak? | |||||

| Yes | 5 (2.9) | 3 (3.8) | 2 (2.2) | 1.734 (0.282–10.647) | 0.550 |

| No | 166 (97.1) | 77 (96.3) | 89 (97.8) | ||

| Hospital provided oral hygiene supplies? | |||||

| Yes | 55 (32.2) | 3 (3.8) | 52 (57.1) | 0.029 (0.009–0.100) | <0.001 ^ |

| No | 116 (67.8) | 77 (96.3) | 39 (42.9) | ||

| If not, did you bring your supplies? | |||||

| Yes | 36 (31.0) | 26 (33.8) | 10 (25.6) | 1.478 (0.626–3.494) | 0.372 |

| No | 80 (69.0) | 51 (66.2) | 29 (74.4) | ||

| Received oral health assessment during stay? | |||||

| Yes | 16 (9.4) | 4 (5.0) | 12 (13.2) | 0.346 (0.107–1.122) | 0.067 |

| No | 155 (90.6) | 76 (95.0) | 79 (86.8) |

| Predictor | B (SE) | AOR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.012 (0.010) | 1.01 | (0.99–1.03) | 0.230 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (Ref.) | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.923 (0.392) | 2.52 | (1.17–5.43) | 0.018 * |

| Nationality | ||||

| Saudi (Ref.) | 1 | |||

| Non-Saudi | 1.363 (0.595) | 3.91 | (1.22–12.55) | 0.022 * |

| Educational level | ||||

| Non-educated (Ref.) | 1 | |||

| Below secondary education | 0.340 (0.555) | 1.41 | (0.47–4.17) | 0.540 |

| Secondary/Diploma | 0.747 (0.563) | 2.11 | (0.70–6.37) | 0.185 |

| Bachelor’s degree/above | 1.733 (0.666) | 5.66 | (1.53–20.88) | 0.009 * |

| Hospital type | ||||

| Public (Ref.) | 1 | |||

| Private | 0.157 (0.358) | 1.17 | (0.58–2.36) | 0.661 |

| Department | ||||

| Medicine (Ref.) | 1 | |||

| Surgery | 0.068 (0.367) | 1.07 | (0.52–2.20) | 0.854 |

| Length of stay (days) | –0.015 (0.019) | 0.99 | (0.95–1.02) | 0.427 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kassem, A.O.; Umer, M.F.; Hamidaddin, M.A.; Nasir, E.F.; Alomran, A.J.; Alsuwayi, H.I.; AlQahtani, M.A.; Mahabob Basha, N.; Bokhari, S.A.H. Oral Hygiene Practices of Hospitalized Patients in Public and Private Hospitals in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8698. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248698

Kassem AO, Umer MF, Hamidaddin MA, Nasir EF, Alomran AJ, Alsuwayi HI, AlQahtani MA, Mahabob Basha N, Bokhari SAH. Oral Hygiene Practices of Hospitalized Patients in Public and Private Hospitals in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8698. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248698

Chicago/Turabian StyleKassem, Amany Osama, Muhammad Farooq Umer, Mohammad Alhussein Hamidaddin, Elwalid Fadul Nasir, Areej Jafar Alomran, Hajar Ibrahim Alsuwayi, Mohammad Abdullah AlQahtani, Nazargi Mahabob Basha, and Syed Akhtar Hussain Bokhari. 2025. "Oral Hygiene Practices of Hospitalized Patients in Public and Private Hospitals in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8698. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248698

APA StyleKassem, A. O., Umer, M. F., Hamidaddin, M. A., Nasir, E. F., Alomran, A. J., Alsuwayi, H. I., AlQahtani, M. A., Mahabob Basha, N., & Bokhari, S. A. H. (2025). Oral Hygiene Practices of Hospitalized Patients in Public and Private Hospitals in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8698. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248698