Comparison of Serum and Cervical Mucus Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Levels in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Healthy Controls

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Inclusion criteria for the PCOS patient group: Women aged between 18 and 40 years who had been diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) were included. The diagnosis of PCOS and phenotypes was established based on the 2003 Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM diagnostic criteria, which rely on ultrasound findings, medical history, clinical features, laboratory parameters, and physical examination.

- Exclusion criteria: Women with a diagnosis or suspicion of any kind of malignancy, history of metformin usage, postmenopausal period, pregnancy, or oral contraceptive therapy within the past three months

- Control group: Women aged between 18 and 40 years who presented for routine check-ups, had regular menstrual cycles, no obstetric or gynecological pathology (such as myoma, endometrioma, etc.), no acute or chronic infections (including upper/lower respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, etc.), and who had not started any medical treatment were included as healthy, voluntary participants.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 17-α OHP | 17-Alpha Hydroxyprogesterone |

| ASRM | American Society for Reproductive Medicine |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| DHEA-S | Dihydroepiandrostenedione Sulfate |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic |

| ESHRE | European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology |

| FPG | Fasting Plasma Glucose |

| FSH | Follicle-Stimulating Hormone |

| fT | Free Testosterone |

| hCG | Human Chorionic Gonadotropin |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| IL-1β | Including Interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LDL | Low-Density Protein |

| LH | Luteinizing Hormone |

| LOX | Lipoxygenase |

| mFGS | modified Ferriman Gallwey Score |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| PRL | Prolactin |

| SPM | Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| TSH | Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone |

| TT | Total Testosterone |

References

- Lizneva, D.; Suturina, L.; Walker, W.; Brakta, S.; Gavrilova-Jordan, L.; Azziz, R. Criteria, prevalence, and phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burghen, G.A.; Givens, J.R.; Kitabchi, A.E. Correlation of Hyperandrogenism with Hyperinsulinism in Polycystic Ovarian Disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1980, 50, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, R.; Basak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Docosahexaenoic acid,22:6n-3: Its roles in the structure and function of the brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2019, 79, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, G.Y.; Simonyi, A.; Fritsche, K.L.; Chuang, D.Y.; Hannink, M.; Gu, Z.; Greenlief, C.M.; Yao, J.K.; Lee, J.C.M.; Beversdorf, D.Q. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA): An essential nutrient and a nutraceutical for brain health and diseases. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 136, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenkci, V.; Fenkci, S.; Yilmazer, M.; Serteser, M. Decreased total antioxidant status and increased oxidative stress in women with polycystic ovary syndrome may contribute to the risk of cardiovascular disease. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 80, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.C.J.; Lyall, H.; Petrie, J.R.; Gould, G.W.; Connell, J.M.C.; Sattar, N. Low Grade Chronic Inflammation in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 2453–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qiao, J. Genetic basis of metabolism and inflammation in PCOS. Hum. Reprod. Prenat. Genet. 2023, 1, 531–563. [Google Scholar]

- Boulman, N.; Levy, Y.; Leiba, R.; Shachar, S.; Linn, R.; Zinder, O.; Blumenfeld, Z.J.T.J.O.C.E. Increased C-Reactive Protein Levels in the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Marker of Cardiovascular Disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regidor, P.A.; Mueller, A.; Sailer, M.; Santos, F.G.; Rizo, J.M.; Egea, F.M. Chronic Inflammation in PCOS: The Potential Benefits of Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators (SPMs) in the Improvement of the Resolutive Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetto, M.; Infante, M.; Sacco, R.L.; Rundek, T.; Della-Morte, D. A Novel Anti-Inflammatory Role of Omega-3 PUFAs in Prevention and Treatment of Atherosclerosis and Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, M.; Kishida, E.; Iwasaki, M.; Kojo, S.; Masuzawa, Y. Docosahexaenoic Acid and Vitamin E Can Reduce Human Monocytic U937 Cell Apoptosis Induced by Tumor Necrosis Factor. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, J.; Yang, J. Eicosapentaenoic Acid Improves Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Rats via Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1 (SREBP 1)/Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Pathway. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouladsahebmadarek, E.; Khaki, A.; Khanahmadi, S.; Ashtiani, H.A.; Paknejad, P.; Ayubi, M.R. Hormonal and metabolic effects of polyunsaturated fatty acid (omega-3) on polycystic ovary syndrome induced rats under diet. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2014, 17, 123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Komal, F.; Khan, M.K.; Imran, M.; Ahmad, M.H.; Anwar, H.; Ashfaq, U.A.; Ahmad, N.; Masroor, N.; Ahmad, R.S.; Nadeem, M.; et al. Impact of different omega-3 fatty acid sources on lipid, hormonal, blood glucose, weight gain and histopathological damages profile in PCOS rat model. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, T.M.; Hanson, P.; Weickert, M.O.; Franks, S. Obesity and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Implications for Pathogenesis and Novel Management Strategies. Clin. Med. Insights Reprod. Health 2019, 13, 117955811987404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Álvarez-Blasco, F.; Botella-Carretero, J.I.; San Millán, J.L.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F. Prevalence and characteristics of the polycystic ovary syndrome in overweight and obese women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 2081–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollila, M.M.E.; Piltonen, T.; Puukka, K.; Ruokonen, A.; Järvelin, M.R.; Tapanainen, J.S.; Franks, S.; Morin-Papunen, L. Weight Gain and Dyslipidemia in Early Adulthood Associate with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasali, E.; Van Cauter, E.; Ehrmann, D.A. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep. Med. Clin. 2008, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoly, N.S.; Khomami, M.B.; Joham, A.E.; Cooray, S.D.; Misso, M.L.; Norman, R.J.; Harrison, C.L.; Ranasinha, S.; Teede, H.J.; Moran, L.J. Ethnicity, obesity and the prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes in PCOS: A systematic review and meta-regression. Hum. Reprod. Update 2018, 24, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, R.A.; Rizzo, M.; Clifton, S.; Carmina, E. Lipid levels in polycystic ovary syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1073–1079.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhija, N.; Tayade, S.; Toshniwal, S.; Tilva, H. Clinico-Metabolic Profile in Lean Versus Obese Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Women. Cureus 2023, 15, e37809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Morreale, H.F.; Luque-Ramírez, M.; González, F. Circulating inflammatory markers in polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1048–1058.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F.; Rote, N.S.; Minium, J.; Kirwan, J.P. Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Oxidative Stress in the Development of Insulin Resistance and Hyperandrogenism in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, Y.; Akcay, T.; Erdem, T.; Ilker Saygili, E.; Gundogdu, S. DNA damage, DNA susceptibility to oxidation and glutathione level in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2009, 65, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Wen, X.; Jia, M.; Shaanxi, M.J. Efficacy of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on hormones, oxidative stress, and inflammatory parameters among polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 8991001–8999001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prostek, A.; Gajewska, M.; Kamola, D.; Bałasińska, B. The influence of EPA and DHA on markers of inflammation in 3T3-L1 cells at different stages of cellular maturation. Lipids Health Dis. 2014, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, K.D.; Van Elswyk, M.E.; Higgins, M.R.; Weatherford, C.A.; Salem, N. Global survey of the omega-3 fatty acids, docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid in the blood stream of healthy adults. Prog. Lipid Res. 2016, 63, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zeng, L.; Bao, T.; Ge, J. Effectiveness of Omega-3 fatty acid for polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, A.; Zeyda, M.; Mascher, D.; Itariu, B.K.; Murano, I.; Leitner, L.; Hochbrugger, E.E.; Fraisl, P.; Cinti, S.; Serhan, C.N.; et al. Impaired Local Production of Proresolving Lipid Mediators in Obesity and 17-HDHA as a Potential Treatment for Obesity-Associated Inflammation. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehuda, S.; Rabinovitz, S.; Mostofsky, D.I. Essential fatty acids and the brain: From infancy to aging. Neurobiol. Aging 2005, 26, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arca, M.; Borghi, C.; Pontremoli, R.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Colivicchi, F.; Desideri, G.; Temporelli, P.L. Hypertriglyceridemia and omega-3 fatty acids: Their often overlooked role in cardiovascular disease prevention. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helland, I.B.; Smith, L.; Saarem, K.; Saugstad, O.D.; Drevon, C.A. Maternal Supplementation with Very-Long-Chain n-3 Fatty Acids During Pregnancy and Lactation Augments Children’s IQ at 4 Years of Age. Pediatrics 2003, 111, e39–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijck-Brouwer, D.A.J.; Hadders-Algra, M.; Bouwstra, H.; Decsi, T.; Boehm, G.; Martini, I.A.; Boersma, E.R.; Muskiet, F.A.J. Lower fetal status of docosahexaenoic acid, arachidonic acid and essential fatty acids is associated with less favorable neonatal neurological condition. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2005, 72, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim-Karakas, S.E.; Almario, R.U.; Gregory, L.; Wong, R.; Todd, H.; Lasley, B.L. Metabolic and Endocrine Effects of a Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid-Rich Diet in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, F. Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids 2012, 77, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, A.; Huynh, K.; Ellery, S.J.; Strauss, B.J.; Joham, A.E.; De Courten, B.; Meikle, P.J.; Teede, H.J. Novel Lipidomic Signature Associated With Metabolic Risk in Women With and Without Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e1987–e1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Shang, J.; Bai, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Song, X. Serum fatty acid profiles associated with metabolic risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1077590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Li, X.; Lv, L.; Xu, Y.; Wu, B.; Huang, C. Dietary and serum n-3 PUFA and polycystic ovary syndrome: A matched case–control study. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | PCOS Group (n = 42) | Control Group (n = 42) | Effect Size | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.00 (26.00–30.00) | 31.00 (27.00–34.00) | −3.00 (−6.35, 0.35) | 0.024 * |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.14 (23.41–31.23) | 25.27 (22.01–27.77) | 1.87 (−0.78, 4.52) | 0.043 * |

| Gravida (n) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) | 1.00 (0.00–2.00) | −1.00 (−2.08, 0.08) | 0.062 † |

| Parity (n) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) | 1.00 (0.00–2.00) | −1.00 (−1.68, −0.32) | 0.005 ** |

| Abortions (n) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.036 * |

| mFGS | 14.50 (10.50–19.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 14.50 (11.52, 17.48) | <0.001 *** |

| Oligo-/amenorrhea n (%) | 36 (85.7%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0.000 * |

| Smoking n (%) | 10 (23.8%) | 7 (16.7%) | 1.56 (0.53, 4.59) | 0.417 |

| Mid-luteal Progesterone (ng/mL) | 0.82 (0.57–4.54) | 8.75 (1.75–13.44) | −7.93 (−10.47, −5.39) | <0.001 *** |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 5.39 (4.39–6.50) | 5.57 (4.66–6.98) | −0.18 (−1.02, 0.66) | 0.426 |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 7.10 (5.16–8.46) | 5.00 (3.88–5.85) | 2.09 (0.81, 3.38) | <0.001 *** |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 44.47 (38.12–55.60) | 51.55 (41.40–69.11) | −7.09 (−15.53, 1.36) | 0.106 |

| PRL (ng/mL) | 10.26 (7.96–12.45) | 9.09 (7.27–13.23) | 1.17 (−1.28, 3.63) | 0.724 |

| TSH (µIU/mL) | 2.41 ± 1.25 | 2.38 ± 1.06 | 0.03 (−0.48, 0.53) | 0.912 |

| Total Testosterone (ng/dL) | 30.49 (9.32) | 22.87 (7.45) | 7.62 (3.93, 11.31) | <0.001 *** |

| DHEA-S (µg/dL) | 226.44 ± 103.22 | 190.18 ± 98.99 | 0.104 | |

| 17-OH Progesterone (ng/mL) | 1.26 ± 0.52 | 0.81 ± 0.41 | 0.44 (0.24, 0.65) | <0.001 *** |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 196.6 ± 34.1 | 185.4 ± 27.7 | 11.14 (−2.35, 24.64) | 0.104 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 48.50 (40.17–53.75) | 51.00 (45.00–59.75) | −2.50 (−8.57, 3.57) | 0.125 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 105.00 (76.25–134.00) | 88.50 (74.00–107.75) | 16.50 (−2.32, 35.32) | 0.273 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 123.59 ± 31.16 | 112.12 ± 27.01 | 11.47 (−1.19, 24.13) | 0.075 † |

| Fasting Blood Glucose (mg/dL) | 86.50 (81.50–93.25) | 87.50 (82.50–93.00) | −1.00 (−4.67, 2.67) | 0.694 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 86.00 (77.25–95.50) | 79.00 (75.00–88.00) | 7.00 (1.06, 12.94) | 0.019 * |

| Hip Circumference (cm) | 106.50 (100.25–115.00) | 102.00 (98.00–110.00) | 4.50 (−1.38, 10.38) | 0.058 † |

| High Waist-to-Hip Ratio | 11 (26.19%) | 4 (9.52%) | 0.30 (0.09, 1.02) | 0.055 † |

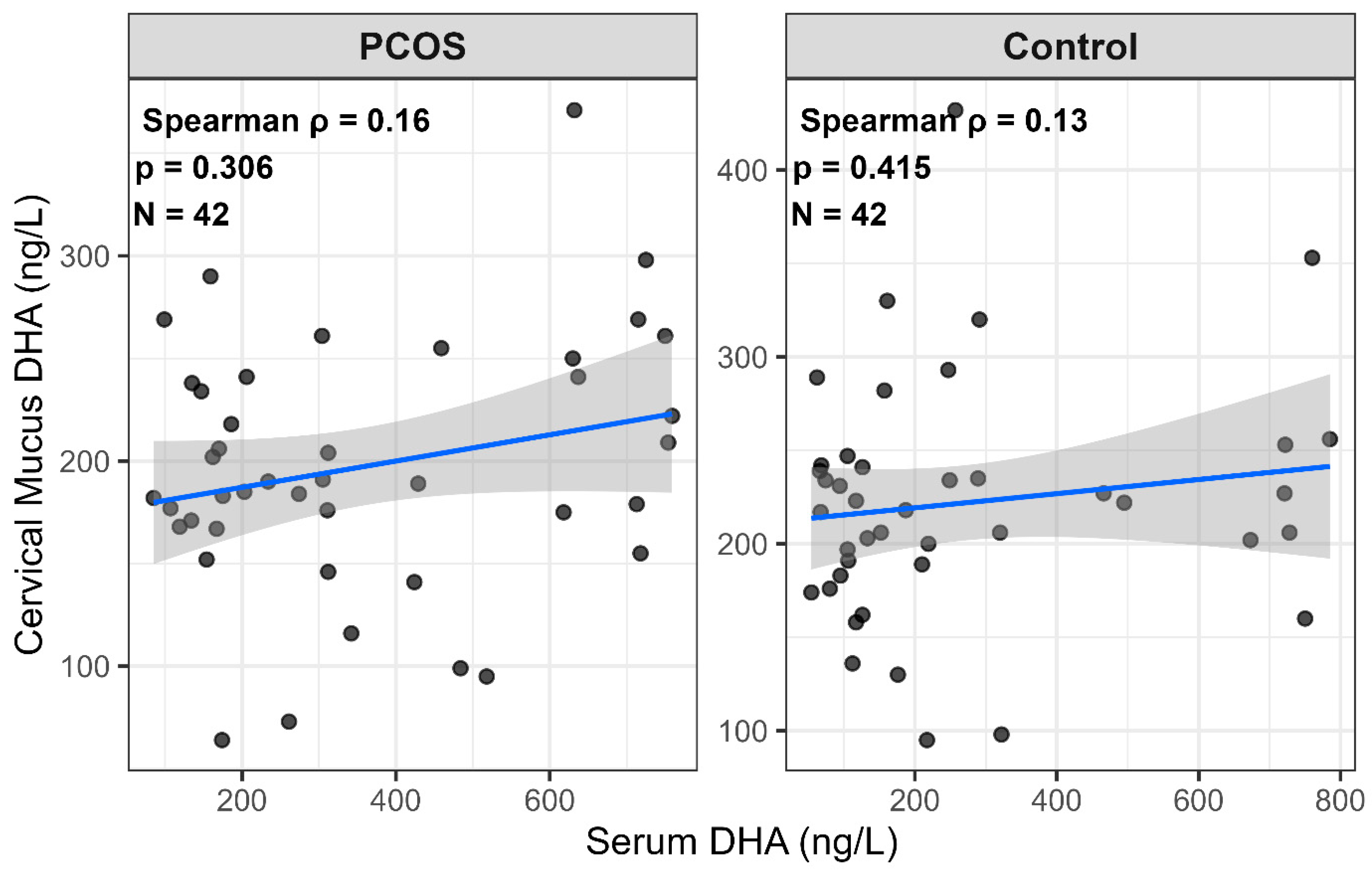

| Serum DHA (ng/L) | 304.50 (167.75–593.00) | 168.50 (105.25–312.75) | 136.00 (18.46, 284.50) | 0.015 * |

| Cervical Mucus DHA (ng/L) | 189.50 (168.75–240.25) | 220.00 (189.50–241.75) | −30.50 (−63.01, −12.00) | 0.098 † |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.25 (2.82–5.50) | 3.15 (2.62–3.80) | 0.10 (−0.90, 0.60) | 0.108 |

| Parameter | PCOS Group (n = 42) | Control Group (n = 42) | Effect Size | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum DHA (ng/L) | 304.50 (167.75–593.00) | 168.50 (105.25–312.75) | 136.00 (18.46, 284.50) | 0.015 * |

| Cervical Mucus DHA (ng/L) | 189.50 (168.75–240.25) | 220.00 (189.50–241.75) | −30.50 (−63.01, −12.00) | 0.098 † |

| Serum-to-cervical mucus DHA ratio | 1.65 (0.85–2.83) | 0.80 (0.52–1.93) | 0.85 (0.10, 1.60) | 0.002 ** |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.25 (2.82–5.50) | 3.15 (2.62–3.80) | 0.10 (−0.90, 0.60) | 0.108 |

| PCOS Phenotype A (n = 42) | PCOS Phenotype C (n = 6) | PCOS Phenotype D (n = 3) | Control (n = 42) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum DHA (ng/L) | 311 (167–618) | 395 (274–637) | 154 (119–174) | 169 (105–320) | 0.023 * |

| Cervical Mucus DHA (ng/L) | 202 (175–241) | 188 (184–241) | 152 (64–168) | 220 (189–242) | 0.073 † |

| Serum-to-cervical mucus DHA ratio | 1.70 [0.83–2.95] | 2.12 [1.49–2.87] | 1.01 [0.71–2.72] | 0.80 [0.52–2.05] | 0.014 * |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.60 (2.90–5.70) | 2.95 (2.70–3.70) | 3.00 (2.60–7.00) | 3.15 (2.60–3.80) | 0.252 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bayrak, C.C.; Yilmaz, B.; Kagitci, M.; Ince, O.; Mataraci Karakas, S.; Yilmaz, A. Comparison of Serum and Cervical Mucus Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Levels in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Healthy Controls. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248899

Bayrak CC, Yilmaz B, Kagitci M, Ince O, Mataraci Karakas S, Yilmaz A. Comparison of Serum and Cervical Mucus Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Levels in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Healthy Controls. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248899

Chicago/Turabian StyleBayrak, Cigdem Can, Bulent Yilmaz, Mehmet Kagitci, Onur Ince, Sibel Mataraci Karakas, and Adnan Yilmaz. 2025. "Comparison of Serum and Cervical Mucus Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Levels in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Healthy Controls" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248899

APA StyleBayrak, C. C., Yilmaz, B., Kagitci, M., Ince, O., Mataraci Karakas, S., & Yilmaz, A. (2025). Comparison of Serum and Cervical Mucus Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Levels in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Healthy Controls. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248899