Early Outcomes of Cruciate-Retaining Versus Posterior-Stabilized Total Knee Arthroplasty in Younger Patients: A Prospective Eastern European Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics and Study Design

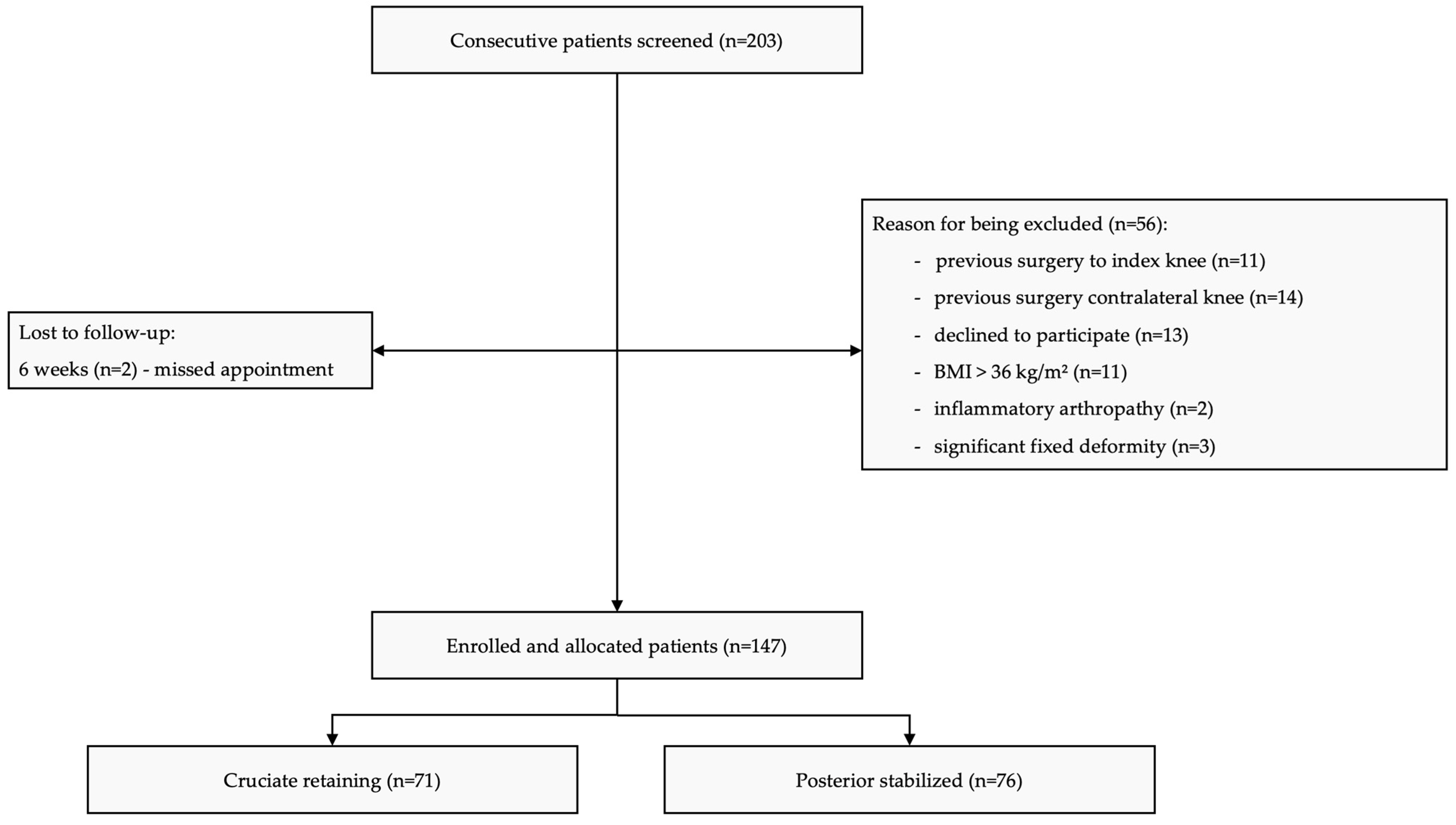

2.2. Participants

2.3. Implant Selection

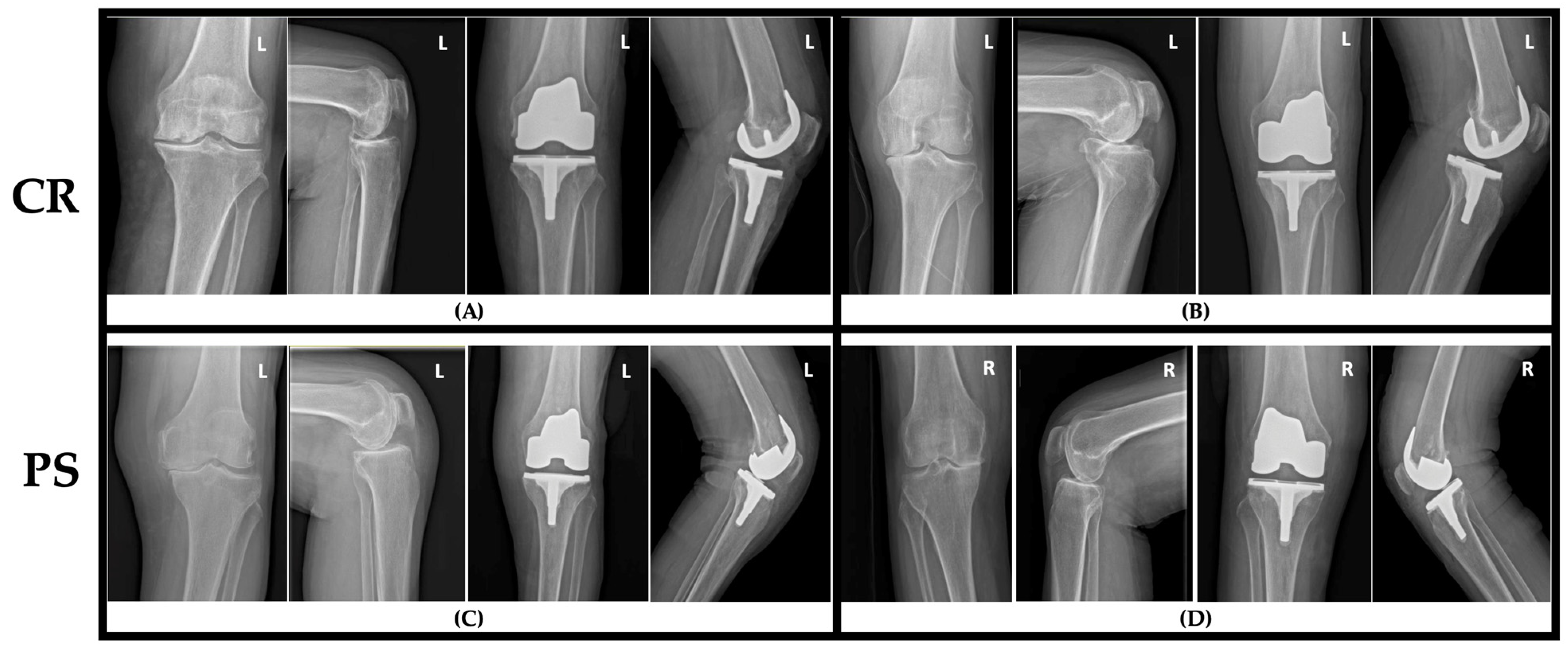

2.4. Surgical Procedure

2.5. Rehabilitation

2.6. Outcomes

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KOA | Knee osteoarthritis |

| TKA | Total knee arthroplasty |

| PS | Posterior-stabilized (implant/design) |

| CR | Cruciate-retaining (implant/design) |

| PCL | Posterior cruciate ligament |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| PROMs | Patient-reported outcome measures |

| LEFS | Lower-Extremity Functional Scale |

| EQ-5D-5L | EuroQol five-dimension, five-level index |

| VAS | Visual analogue scale |

| PROMIS | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Depression |

| FJS | Forgotten Joint Score |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| POLO | Pull-Out–Lift-Off test |

References

- Sutton, P.M.; Holloway, E.S. The young osteoarthritic knee: Dilemmas in management. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, I.N.; Kemp, J.L.; Crossley, K.M.; Culvenor, A.G.; Hinman, R.S. Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis Affects Younger People, Too. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2017, 47, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, J.F.; Purita, J.; Jeyaraman, M.; de Souza, B.F.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Huber, S.C.; Caliari, C.; Santos, G.S.; da Fonseca, L.F.; Dallo, I.; et al. Innovative Approaches in Knee Osteoarthritis Treatment: A Comprehensive Review of Bone Marrow-Derived Products. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tille, E.; Beyer, F.; Lützner, C.; Postler, A.; Lützner, J. Better Flexion but Unaffected Satisfaction After Treatment with Posterior Stabilized Versus Cruciate Retaining Total Knee Arthroplasty—2-year Results of a Prospective, Randomized Trial. J. Arthroplast. 2024, 39, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spekenbrink-Spooren, A.; Van Steenbergen, L.N.; Denissen, G.A.W.; Swierstra, B.A.; Poolman, R.W.; Nelissen, R.G.H.H. Higher mid-term revision rates of posterior stabilized compared with cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasties: 133,841 cemented arthroplasties for osteoarthritis in the Netherlands in 2007–2016. Acta Orthop. 2018, 89, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaballa, E.; Ntani, G.; Harris, E.C.; Arden, N.K.; Cooper, C.; Walker-Bone, K. Return to work and employment retention after uni-compartmental and total knee replacement: Findings from the Clinical Outcomes in Arthroplasty study. Knee 2023, 40, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, G.A.; Cassidy, R.S.; McKee, C.; Hughes, I.; Hill, J.C.; Beverland, D.E. Survivorship of 500 Cementless Total Knee Arthro-plasties in Patients Under 55 Years of Age. J. Arthroplast. 2023, 38, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moewis, P.; Duda, G.N.; Trepczynski, A.; Krahl, L.; Boese, C.K.; Hommel, H. Retention of Posterior Cruciate Ligament Alone May Not Achieve Physiological Knee Joint Kinematics After Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Retrospective Study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2021, 103, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Most, E.; Zayontz, S.; Li, G.; Otterberg, E.; Sabbag, K.; Rubash, H.E. Femoral rollback after cruciate-retaining and stabilizing total knee arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2003, 410, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, M.V.; Scott, D.L.; Rees, J.; Newham, D.J. Sensorimotor changes and functional performance in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1997, 56, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- D’Ambrosi, R.; Menon, P.H.; Salunke, A.; Mariani, I.; Palminteri, G.; Basile, G.; Ursino, N.; Mangiavini, L.; Hantes, M. Octogenarians Are the New Sexagenarians: Cruciate-Retaining Total Knee Arthroplasty Is Not Inferior to Posterior-Stabilized Arthroplasty in Octogenarian Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J. Posterior Cruciate-Retaining vs Posterior Cruciate-Stabilized Prosthesis in Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Meta-Analysis. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2023, 29, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vitalis, L.; Feier, A.-M.; Russu, O.; Zuh, S.-G.; Szórádi, G.-T.; Pop, T.S. Evaluating a Tailored 12-Week Post-Operative Reha-bilitation Program for Younger Patients Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: Addressing a Growing Need. Balneo PRM Res. J. 2023, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, J.M.; Stratford, P.W.; Lott, S.A.; Riddle, D.L. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): Scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. Phys. Ther. 1999, 79, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.P.; Fulton, A.; Quach, C.; Thistle, M.; Toledo, C.; Evans, N.A. Measurement Properties of the Lower Extremity Functional Scale: A Systematic Review. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna-Berna, R.; Lizaur-Utrilla, A.; Vizcaya-Moreno, M.F.; Miralles Muñoz, F.A.; Gonzalez-Navarro, B.; Lopez-Prats, F.A. Cruci-ate-Retaining vs Posterior-Stabilized Primary Total Arthroplasty. Clinical Outcome Comparison with a Minimum Follow-Up of 10 Years. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 2491–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dong, M.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhao, R.; Wei, X. Comparison of posterior cruciate retention and substitution in total knee arthroplasty during gait: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodland, N.; Takla, A.; Estee, M.M.; Franks, A.; Bhurani, M.; Liew, S.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Wang, Y. Patient-Reported Outcomes following Total Knee Replacement in Patients Aged 65 Years and Over-A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, D.C.; Yousef, M.; Yang, W.; Zheng, H. Age-Related Differences in Pain, Function, and Quality of Life Following Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: Results From a FORCE-TJR (Function and Outcomes Research for Comparative Effectiveness in Total Joint Replacement) Cohort. J. Arthroplast. 2023, 38, S169–S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Estrada, E.I.; Ramírez-Yañez, E.; Álvarez-Alarcón, G.; Muñoz-Nieto, D.; Villaseñor-Valdés, J.J.; Núñez-García, L.A. Comparative Outcomes Between Cruciate-Retaining and Posterior-Stabilized Prostheses in Total Knee Arthroplasty. Cureus 2025, 17, e87465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, E.R.; Zheng, H.; Markel, D.C.; Hallstrom, B.R.; Hughes, R.E. Variation in KOOS JR improvement across total knee implant designs: A cohort study from Michigan Arthroplasty Registry Collaborative Quality Initiative. Acta Orthop. 2025, 96, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, N.B.; Brush, P.L.; Santana, A.; Fras, S.I.; Jenkins, E.; Saxena, A. Dissatisfaction and Residual Symptoms in Younger and Older Adult Patients after Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. Glob. Res. Rev. 2025, 9, e25.00167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemans, J.; Banks, S.; Victor, J.; Vandenneucker, H.; Moemans, A. Fluoroscopic analysis of the kinematics of deep flexion in total knee arthroplasty. Influence of posterior condylar offset. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2002, 84, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDuc, R.C.; Upadhyay, D.; Brown, N.M. Cruciate-Retaining Versus Cruciate-Substituting Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Me-ta-Analysis. Indian J. Orthop. 2023, 57, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | PS (n = 76) | CR (n = 71) |

|---|---|---|

| Female, yes (%) | 41 (53.9) | 43 (60.6) |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 57.2 ± 6.1 | 58.7 ± 6.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 29.1 ± 4.2 | 28.7 ± 4.4 |

| Rural residence, no (%) | 32 (42.1) | 28 (39.4) |

| Smoker, yes (%) | 18 (23.7) | 15 (21.1) |

| Alcohol use, regular, yes (%) | 12 (15.8) | 11 (15.5) |

| Employed at time of surgery, no (%) | 21 (27.6) | 20 (28.2) |

| Ahlbäck Grade | PS | CR | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade III, no (%) | 18 (23.7) | 20 (28.2) | 0.72 |

| Grade IV, no (%) | 28 (36.8) | 32 (45.1) | 0.41 |

| Grade V, no (%) | 30 (39.5) | 19 (26.8) | 0.09 |

| Follow-Up | Mean ΔLEFS * | 95% CI Low | 95% CI High | p-Value | MCID (%) | 95% CI Low | 95% CI High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks | 0.57 | −0.14 | 1.27 | 0.113 | 17.1 | 2.1 | 31.1 |

| 3 months | 0.27 | −0.94 | 1.48 | 0.661 | 5.9 | −4.9 | 15.6 |

| 6 months | −0.28 | −1.88 | 1.31 | 0.724 | 6.0 | −5.3 | 16.0 |

| 12 months | 0.14 | −1.61 | 1.88 | 0.876 | 6.3 | −5.8 | 16.3 |

| Baseline | 6 Weeks | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | ||||||

| CR | PS | CR | PS | CR | PS | CR | PS | CR | PS | ||||||

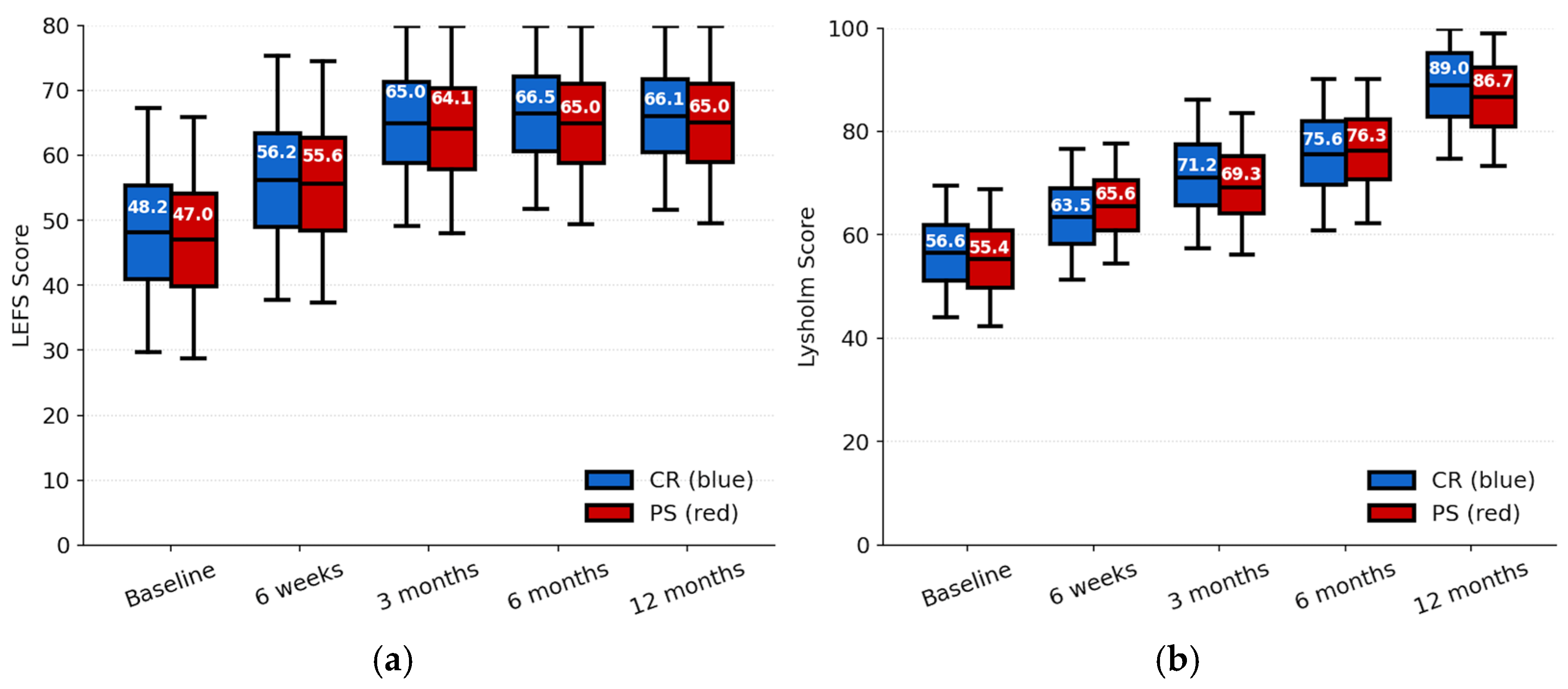

| LEFS | 48.2 ± 14.8 | 47.0 ± 14.6 | 0.63 | 56.2 ± 14.8 | 55.6 ± 14.6 | 0.80 | 65.0 ± 12.8 | 64.1 ± 12.9 | 0.66 | 66.5 ± 11.8 | 65.0 ± 12.4 | 0.46 | 66.1 ± 11.6 | 65.0 ± 12.43 | 0.60 |

| Lysholm | 56.6 ± 10.0 | 55.4 ± 10.4 | 0.47 | 63.5 ± 10.0 | 65.6 ± 9.1 | 0.18 | 71.2 ± 11.4 | 69.3 ± 10.8 | 0.30 | 75.6 ± 11.2 | 76.3 ± 10.7 | 0.69 | 89.0 ± 11.4 | 86.7 ± 10.6 | 0.20 |

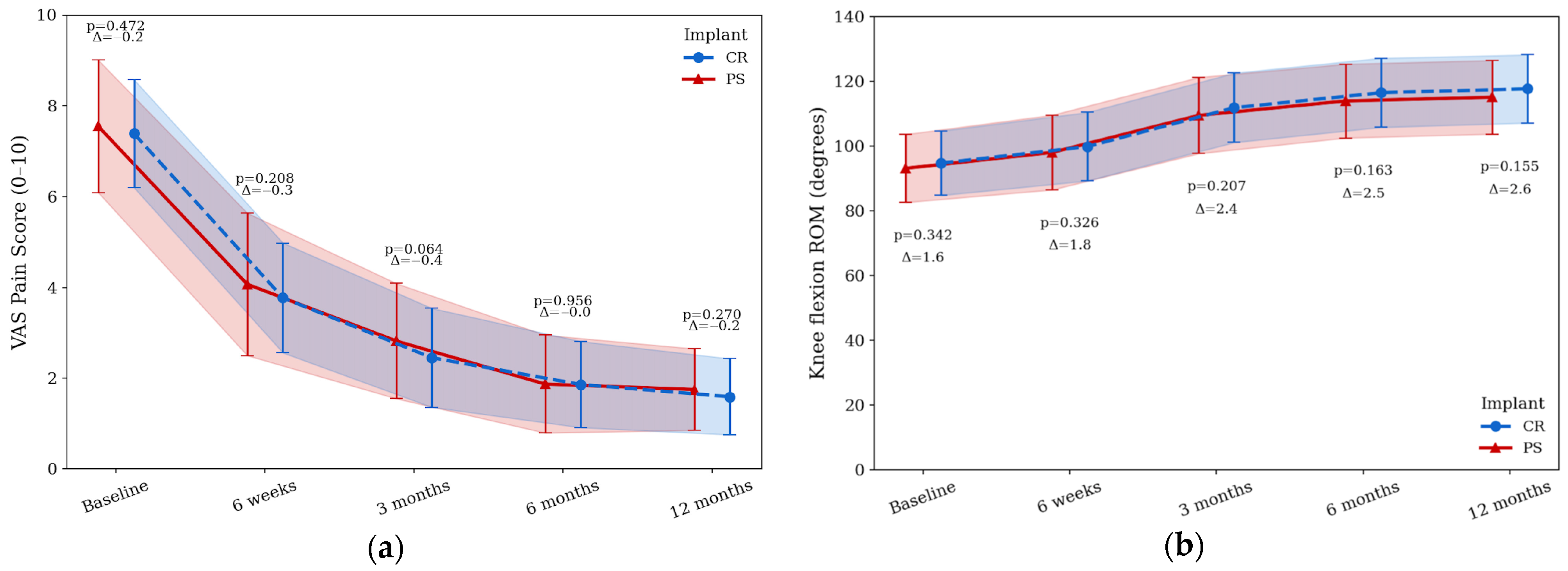

| Flexion | 94.6 ± 9.9 | 93.0 ± 10.5 | 0.34 | 99.7 ± 10.5 | 97.9 ± 11.5 | 0.32 | 111.7 ± 10.7 | 109.3 ± 11.7 | 0.20 | 116.3 ± 10.6 | 113.8 ± 11.4 | 0.16 | 117.5 ± 10.5 | 115.0 ± 11.3 | 0.15 |

| Baseline | 6 Weeks | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | ||||||

| CR | PS | CR | PS | CR | PS | CR | PS | CR | PS | ||||||

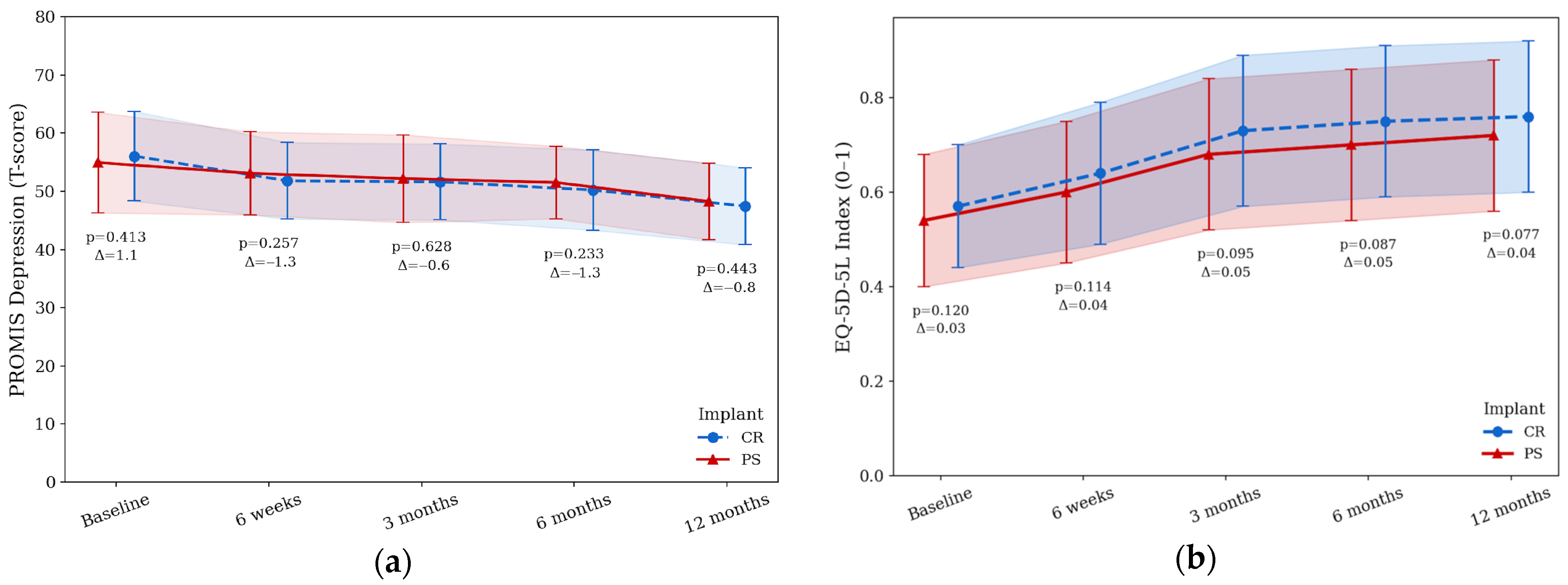

| EQ-5D-5L | 0.57 ± 0.13 | 0.54 ± 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.60 ± 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.73 ± 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.16 | 0.95 | 0.75 ± 0.16 | 0.70 ± 0.16 | 0.87 | 0.76 ± 0.16 | 0.72 ± 0.16 | 0.07 |

| VAS | 7.39 ± 1.19 | 7.55 ± 1.46 | 0.47 | 3.77 ± 1.21 | 4.07 ± 1.57 | 0.20 | 2.45 ± 1.09 | 2.82 ± 1.27 | 0.06 | 1.86 ± 0.95 | 1.87 ± 1.08 | 0.95 | 1.59 ± 0.84 | 1.75 ± 0.90 | 0.27 |

| PROMIS | 56.06 ± 7.7 | 54.95 ± 8.6 | 0.41 | 51.82 ± 6.5 | 53.11 ± 7.1 | 0.25 | 51.63 ± 6.5 | 52.20 ± 7.5 | 0.62 | 50.23 ± 6.8 | 51.53 ± 6.2 | 0.23 | 47.45 ± 6.6 | 48.29 ± 6.5 | 0.44 |

| Satisfaction | n/a | n/a | n/a | 5.83 ± 1.40 | 6.01 ± 1.53 | 0.45 | 7.23 ± 1.24 | 7.04 ± 1.37 | 0.39 | 7.97 ± 1.13 | 7.92 ± 1.19 | 0.79 | 8.14 ± 1.02 | 8.17 ± 1.22 | 0.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vitalis, L.; Feier, A.M.; Zuh, S.G.; Russu, O.M.; Pop, T.S. Early Outcomes of Cruciate-Retaining Versus Posterior-Stabilized Total Knee Arthroplasty in Younger Patients: A Prospective Eastern European Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8893. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248893

Vitalis L, Feier AM, Zuh SG, Russu OM, Pop TS. Early Outcomes of Cruciate-Retaining Versus Posterior-Stabilized Total Knee Arthroplasty in Younger Patients: A Prospective Eastern European Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8893. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248893

Chicago/Turabian StyleVitalis, Lorand, Andrei Marian Feier, Sandor György Zuh, Octav Marius Russu, and Tudor Sorin Pop. 2025. "Early Outcomes of Cruciate-Retaining Versus Posterior-Stabilized Total Knee Arthroplasty in Younger Patients: A Prospective Eastern European Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8893. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248893

APA StyleVitalis, L., Feier, A. M., Zuh, S. G., Russu, O. M., & Pop, T. S. (2025). Early Outcomes of Cruciate-Retaining Versus Posterior-Stabilized Total Knee Arthroplasty in Younger Patients: A Prospective Eastern European Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8893. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248893