Guts, Glucose, and Gallbladders: The Protective Role of GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonists Against Biliary Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Source and Study Design

3. Cohort Definition

- Cohort 1 (Exposed Group): Patients with T2DM and IBD prescribed semaglutide or tirzepatide.

- Cohort 2 (Control Group): Patients with T2DM and IBD not prescribed any GLP-1 or GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist.

4. Outcomes

4.1. Cholelithiasis

- K80.00–K80.21—Calculus of gallbladder with or without cholecystitis or obstruction

- K80.50–K80.51—Calculus of bile duct without cholangitis or cholecystitis, with or without obstruction

4.2. Cholecystitis

- K81.0—Acute cholecystitis

- K81.1—Chronic cholecystitis

- K81.2—Acute on chronic cholecystitis

- K81.9—Cholecystitis, unspecified

4.3. Choledocholithiasis

- K80.30–K80.41—Calculus of bile duct with cholangitis or cholecystitis, with or without obstruction

- K80.60–K80.73—Calculus of bile duct without cholangitis or cholecystitis, with or without obstruction

4.4. Cholangitis

- K83.0—Cholangitis

- K83.01—Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- K83.09—Other cholangitis

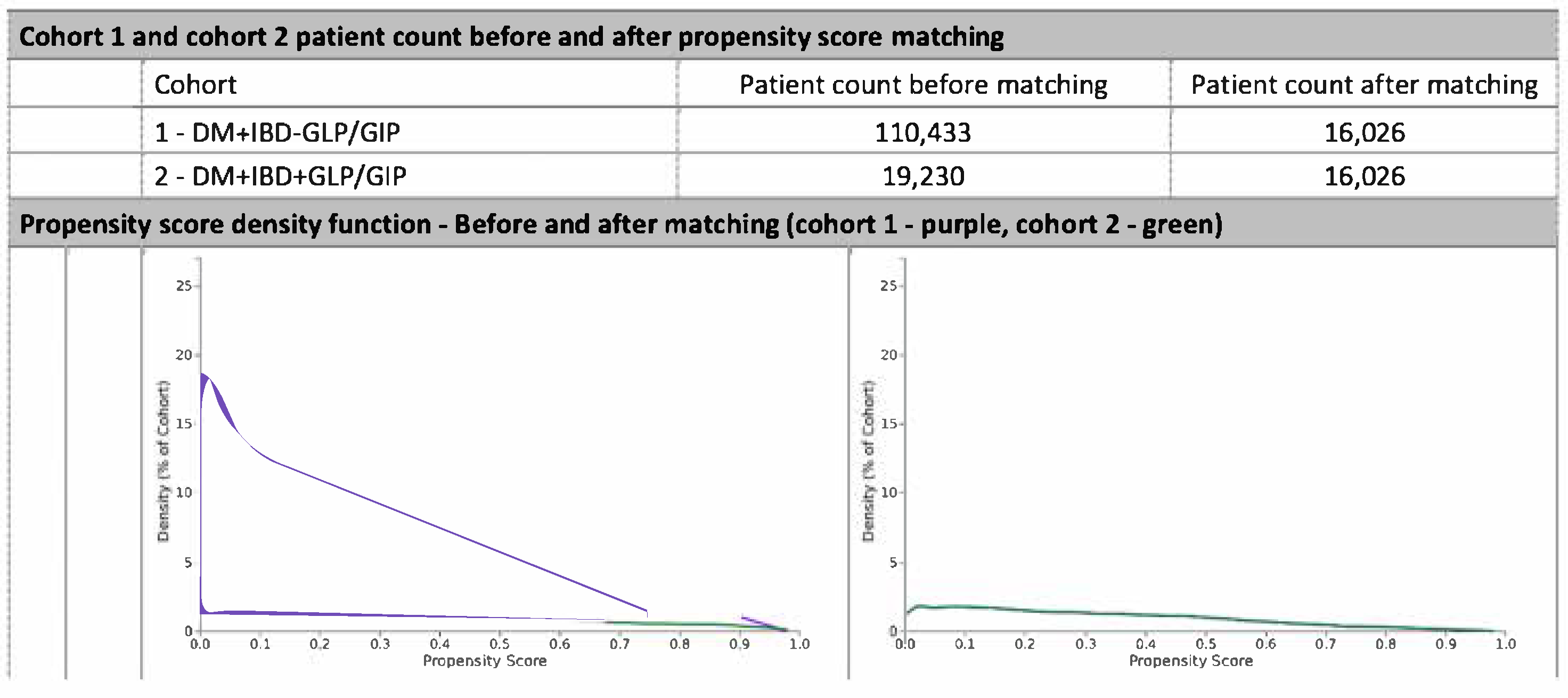

5. Propensity Score Matching

5.1. Statistical Analysis

5.2. Sensitivity Analyses

- Exclusion of Prior Biliary Disease: Analyses were repeated after excluding patients with any biliary diagnosis (ICD-10 codes K80–K83) prior to the index date to eliminate baseline bias.

- Subgroup Analysis by Drug Class: Separate analyses were conducted for patients exposed to GLP-1 receptor agonists (semaglutide) versus dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists (tirzepatide).

- Follow-up Duration Restriction: Outcomes were reassessed after restricting follow-up to 12 months post-index to address potential time-dependent bias.

- Alternative Matching Algorithm: Results were compared using an alternative matching strategy employing a caliper of 0.05 SD of the logit of the propensity score to assess consistency in treatment effect estimates.

6. Results

6.1. Cohort Matching and Baseline Characteristics

6.2. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

6.3. Biliary Outcomes

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, M.A.B.; Hashim, M.J.; King, J.K.; Govender, R.D.; Mustafa, H.; Al Kaabi, J. Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes—Global Burden of Disease and Forecasted Trends. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Truta, B.; Begum, F.; Datta, L.W.; NIDDK IBD Genetics Consortium; Brant, S.R. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Before and After 1990. Gastro. Hep. Adv. 2023, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hyun, C.K. Molecular and Pathophysiological Links between Metabolic Disorders and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, C.H.; Lin, C.L.; Hsu, C.Y.; Kao, C.H. Association Between Type I and II Diabetes with Gallbladder Stone Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hong, R.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Dai, Y. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2025, 18, 17562848241311165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iatcu, C.O.; Steen, A.; Covasa, M. Gut Microbiota and Complications of Type-2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2021, 14, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hunt, J.E.; Holst, J.J.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Kissow, H. GLP-1 and Intestinal Diseases. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Drucker, D.J. Efficacy and Safety of GLP-1 Medicines for Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1873–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frías, J.P.; Davies, M.J.; Rosenstock, J.; Pérez Manghi, F.C.; Fernández Landó, L.; Bergman, B.K.; Liu, B.; Cui, X.; Brown, K.; SURPASS-2 Investigators. Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide Once Weekly in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, R.; Basheer, F.T.; Poojari, P.G.; Thunga, G.; Chandran, V.P.; Acharya, L.D. Adverse drug reactions of GLP-1 agonists: A systematic review of case reports. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2022, 16, 102427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Wang, J.; Ping, F.; Yang, N.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, H. Association of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Use with Risk of Gallbladder and Biliary Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alchirazi, K.; Alsabbagh, K.; Baliss, M.; El Telbany, A.; Alsabbagh, M.; Alsakarneh, S.; Kiwan, W.; Bilal, M. S181 Impact of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist on Gallbladder and Biliary Diseases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.P.; Bain, I.M.; Kumar, D.; Dowling, R.H. Bile composition in inflammatory bowel disease: Ileal disease and colectomy, but not colitis, induce lithogenic bile. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 17, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, B.G.; Gavaler, J.S.; Belle, S.H.; Shreiner, D.P.; Peleman, R.R.; Sarva, R.P.; Yingvorapant, N.; Van Thiel, D.H. Impairment of gallbladder emptying in diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology 1988, 95, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrikou, E.; Tsioufis, C.; Andrikou, I.; Leontsinis, I.; Tousoulis, D.; Papanas, N. GLP-1 receptor agonists and cardiovascular outcome trials: An update. Hell. J. Cardiol. 2019, 60, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, R.; Ding, Y.; Yang, K.; Meng, X.; Sun, X. Association between various insulin resistance surrogates and gallstone disease based on national health and nutrition examination survey. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.H. Anti-inflammatory role of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and its clinical implications. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 15, 20420188231222367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mehdi, S.F.; Pusapati, S.; Anwar, M.S.; Lohana, D.; Kumar, P.; Nandula, S.A.; Nawaz, F.K.; Tracey, K.; Yang, H.; LeRoith, D.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1: A multi-faceted anti-inflammatory agent. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wadden, T.A.; Chao, A.M.; Moore, M.; Tronieri, J.S.; Gilden, A.; Amaro, A.; Leonard, S.; Jakicic, J.M. The Role of Lifestyle Modification with Second-Generation Anti-obesity Medications: Comparisons, Questions, and Clinical Opportunities. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Category | Cohort 1 Patients | Cohort 2 Patients | % of Cohort 1 | % of Cohort 2 | p-Value | Standardized Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Index | 16,026 | 16,026 | 100% | 100% | 0.096 | 0.019 |

| White | 12,430 | 12,346 | 77.6% | 77.0% | 0.263 | 0.013 |

| Unknown Race | 519 | 523 | 3.2% | 3.3% | 0.900 | 0.001 |

| Female | 9669 | 9463 | 60.3% | 59.0% | 0.019 | 0.026 |

| Unknown Ethnicity | 2335 | 2213 | 14.6% | 13.8% | 0.051 | 0.022 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 12,717 | 12,878 | 79.4% | 80.4% | 0.025 | 0.025 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 974 | 935 | 6.1% | 5.8% | 0.357 | 0.010 |

| Black or African American | 2150 | 2180 | 13.4% | 13.6% | 0.624 | 0.005 |

| Male | 6341 | 6553 | 39.6% | 40.9% | 0.016 | 0.027 |

| Category | Cohort 1 Patients | Cohort 2 Patients | % of Cohort 1 | % of Cohort 2 | p-Value | Standardized Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1224 | 1287 | 7.6% | 8.0% | 0.190 | 0.015 |

| Anal abscess | 216 | 243 | 1.3% | 1.5% | 0.204 | 0.014 |

| Anal fistula | 286 | 296 | 1.8% | 1.8% | 0.676 | 0.005 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3540 | 3584 | 22.1% | 22.4% | 0.554 | 0.007 |

| Chronic vascular intestinal disorder | 82 | 92 | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.447 | 0.008 |

| Liver disease | 5114 | 5122 | 31.9% | 32.0% | 0.924 | 0.001 |

| Intestinal fistula | 215 | 206 | 1.3% | 1.3% | 0.659 | 0.005 |

| Heart failure | 2624 | 2679 | 16.4% | 16.7% | 0.408 | 0.009 |

| HIV | 124 | 136 | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.455 | 0.008 |

| Ischiorectal abscess | 106 | 119 | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.384 | 0.010 |

| Neoplasms | 9142 | 9178 | 57.0% | 57.3% | 0.684 | 0.005 |

| Nicotine dependence | 3122 | 3159 | 19.5% | 19.7% | 0.603 | 0.006 |

| Other infections | 338 | 336 | 2.1% | 2.1% | 0.938 | 0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2402 | 2464 | 15.0% | 15.4% | 0.335 | 0.011 |

| COPD | 2296 | 2325 | 14.3% | 14.5% | 0.645 | 0.005 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1523 | 1592 | 9.5% | 9.9% | 0.193 | 0.015 |

| Other rheumatoid arthritis | 1077 | 1122 | 6.7% | 7.0% | 0.320 | 0.011 |

| Obesity | 11,093 | 10,855 | 69.2% | 67.7% | 0.004 | 0.032 |

| Peptic ulcer | 393 | 395 | 2.5% | 2.5% | 0.942 | 0.001 |

| Rectal abscess | 239 | 278 | 1.5% | 1.7% | 0.084 | 0.019 |

| RA with RF | 263 | 266 | 1.6% | 1.7% | 0.895 | 0.001 |

| Connective tissue disease | 660 | 654 | 4.1% | 4.1% | 0.866 | 0.002 |

| Dementia | 199 | 217 | 1.2% | 1.4% | 0.374 | 0.010 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 872 | 896 | 5.4% | 5.6% | 0.557 | 0.007 |

| Category | Cohort 1 Patients | Cohort 2 Patients | % of Cohort 1 | % of Cohort 2 | p-Value | Standardized Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colectomy, partial | 127 | 127 | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Surgical Procedures on Colon & Rectum | 7219 | 7318 | 45.0% | 45.7% | 0.267 | 0.012 |

| Intestinal surgery (non-rectum) | 1003 | 1001 | 6.3% | 6.2% | 0.963 | 0.001 |

| Stomach surgery | 341 | 367 | 2.1% | 2.3% | 0.323 | 0.011 |

| Category | Cohort 1 Patients | Cohort 2 Patients | % of Cohort 1 | % of Cohort 2 | p-Value | Standardized Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INSULIN | 8195 | 8201 | 51.1% | 51.2% | 0.947 | 0.001 |

| canagliflozin | 476 | 514 | 3.0% | 3.2% | 0.220 | 0.014 |

| dapagliflozin | 893 | 998 | 5.6% | 6.2% | 0.013 | 0.028 |

| empagliflozin | 2067 | 2324 | 12.9% | 14.5% | <0.001 | 0.047 |

| acarbose | 67 | 62 | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.659 | 0.005 |

| ertugliflozin | 42 | 48 | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.527 | 0.007 |

| glimepiride | 1516 | 1535 | 9.5% | 9.6% | 0.718 | 0.004 |

| bexagliflozin | 10 | 10 | 0.1% | 0.1% | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| sotagliflozin | 0 | 10 | 0% | 0.1% | 0.002 | 0.035 |

| glyburide | 523 | 511 | 3.3% | 3.2% | 0.704 | 0.004 |

| glipizide | 2199 | 2239 | 13.7% | 14.0% | 0.518 | 0.007 |

| sitagliptin | 2025 | 2057 | 12.6% | 12.8% | 0.592 | 0.006 |

| metformin | 9595 | 9517 | 59.9% | 59.4% | 0.375 | 0.010 |

| repaglinide | 182 | 185 | 1.1% | 1.2% | 0.875 | 0.002 |

| rosiglitazone | 55 | 54 | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.924 | 0.001 |

| saxagliptin | 148 | 150 | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.907 | 0.001 |

| Glucocorticoids | 12,784 | 12,722 | 79.8% | 79.4% | 0.390 | 0.010 |

| Immune suppressants | 2478 | 2510 | 15.5% | 15.7% | 0.622 | 0.006 |

| Other antirheumatics | 2249 | 2291 | 14.0% | 14.3% | 0.501 | 0.008 |

| Outcome | Events (GLP/GIP) | Events (No GLP/GIP) | Risk (GLP/GIP) | Risk (No GLP/GIP) | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholelithiasis | 555 | 1005 | 0.035 | 0.063 | 0.552 (0.499–0.611) | 0.788 (0.708–0.877) | <0.001 |

| Cholecystitis | 129 | 353 | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.365 (0.299–0.447) | 0.541 (0.440–0.666) | <0.001 |

| Choledocholithiasis | 90 | 245 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.367 (0.289–0.467) | 0.526 (0.410–0.674) | <0.001 |

| Cholangitis | 18 | 34 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.529 (0.299–0.937) | 0.935 (0.507–1.724) | 0.080 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kazi, M.A.I.; Singh, S.; Haq, N. Guts, Glucose, and Gallbladders: The Protective Role of GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonists Against Biliary Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248882

Kazi MAI, Singh S, Haq N. Guts, Glucose, and Gallbladders: The Protective Role of GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonists Against Biliary Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248882

Chicago/Turabian StyleKazi, Muhammad Ali Ibrahim, Sanmeet Singh, and Nowreen Haq. 2025. "Guts, Glucose, and Gallbladders: The Protective Role of GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonists Against Biliary Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Inflammatory Bowel Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248882

APA StyleKazi, M. A. I., Singh, S., & Haq, N. (2025). Guts, Glucose, and Gallbladders: The Protective Role of GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonists Against Biliary Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248882