Intravascular Imaging-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Transforming Precision and Outcomes in Contemporary Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Technological Overview of Intravascular Imaging

3.1. IVUS

3.2. OCT

3.3. NIRS

3.4. Rationale for Imaging-Guided PCI

3.5. Key Clinical Evidence

3.6. Imaging-Guided PCI Workflow

3.7. Special Scenarios

3.8. Barriers and Challenges

3.8.1. Economic Misalignment vs. Value-Based Care

3.8.2. The Expertise Gap and Educational Standardization

3.8.3. Operational Efficiency and Workflow Integration

3.8.4. Policy and Guideline Enforcement

4. Limitations of Evidence and Areas of Controversy

4.1. Comparative Equivalence and the “Ceiling Effect”

4.2. Technical “Blind Spots” and Interpretation Challenges

4.3. Procedural Risks in Vulnerable Populations

5. Discussion

6. Recent Developments and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truesdell, A.G.; Alasnag, M.A.; Kaul, P.; Rab, S.T.; Riley, R.F.; Young, M.N.; Batchelor, W.B.; Maehara, A.; Welt, F.G.; Kirtane, A.J. Intravascular Imaging During Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

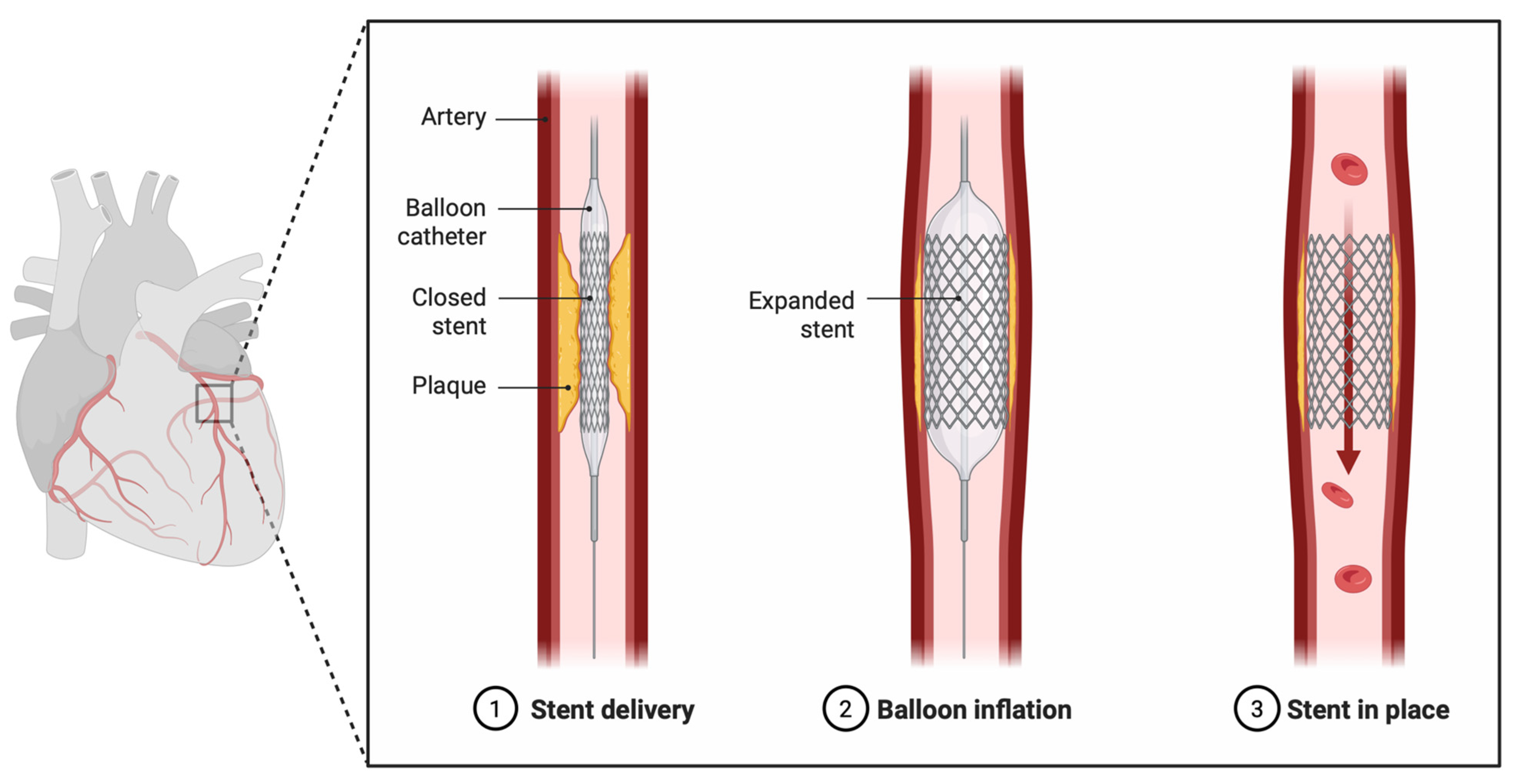

- Alqawasmi, M. Created in BioRender. 2025. Available online: https://biorender.com/yr8q7oj (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Yock, P.G.; Linker, D.T.; Angelsen, B.A.J. Tech Two-Dimensional Intravascular Ultrasound: Technical Development and Initial Clinical Experience. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 1989, 2, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Swanson, E.A.; Lin, C.P.; Schuman, J.S.; Stinson, W.G.; Chang, W.; Hee, M.R.; Flotte, T.; Gregory, K.; Puliafito, C.A.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography. Science 1991, 254, 1178–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.M.; Choi, K.H.; Song, Y.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.M.; Yun, K.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, C.J.; et al. Intravascular Imaging–Guided or Angiography-Guided Complex PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1668–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonetsu, T.; Suh, W.; Abtahian, F.; Kato, K.; Vergallo, R.; Kim, S.-J.; Jia, H.; McNulty, I.; Lee, H.; Jang, I.-K. Comparison of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Optical Coherence Tomography for Detection of Lipid. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 84, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Regar, E.; Mintz, G.S.; Arbustini, E.; Di Mario, C.; Jang, I.-K.; Akasaka, T.; Costa, M.; Guagliumi, G.; Grube, E.; et al. Expert Review Document on Methodology, Terminology, and Clinical Applications of Optical Coherence Tomography: Physical Principles, Methodology of Image Acquisition, and Clinical Application for Assessment of Coronary Arteries and Atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnaird, T.; Johnson, T.; Anderson, R.; Gallagher, S.; Sirker, A.; Ludman, P.; De Belder, M.; Copt, S.; Oldroyd, K.; Banning, A.; et al. Intravascular Imaging and 12-Month Mortality After Unprotected Left Main Stem PCI. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzotta, F.; Louvard, Y.; Lassen, J.F.; Lefèvre, T.; Finet, G.; Collet, C.; Legutko, J.; Lesiak, M.; Hikichi, Y.; Albiero, R.; et al. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Bifurcation Coronary Lesions Using Optimised Angiographic Guidance: The 18th Consensus Document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 2024, 20, e915–e926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.; Hong, D.; Singh, M.; Lee, S.H.; Sakai, K.; Dakroub, A.; Malik, S.; Maehara, A.; Shlofmitz, E.; Stone, G.W.; et al. Intravascular Imaging-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Heavily Calcified Coronary Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 40, 1653–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacoppo, D.; Laudani, C.; Occhipinti, G.; Spagnolo, M.; Greco, A.; Rochira, C.; Agnello, F.; Landolina, D.; Mauro, M.S.; Finocchiaro, S.; et al. Coronary Angiography, Intravascular Ultrasound, and Optical Coherence Tomography for Guiding of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2024, 149, 1065–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Wu, H.; Kim, S.; Dai, X.; Jiang, X. Recent Advances in Transducers for Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) Imaging. Sensors 2021, 21, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabris, E.; Stone, G.W. Intravascular Imaging Guidance of Left Main PCI. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 358–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, A.; Klauss, V. Virtual Histology. Heart Br. Card. Soc. 2007, 93, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aumann, S.; Donner, S.; Fischer, J.; Müller, F. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): Principle and Technical Realization. In High Resolution Imaging in Microscopy and Ophthalmology: New Frontiers in Biomedical Optics; Bille, J.F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-16637-3. [Google Scholar]

- Longobardo, L.; Mattesini, A.; Valente, S.; Di Mario, C. OCT-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Bifurcation Lesions. Interv. Cardiol. Lond. Engl. 2019, 14, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, M. Novel Applications of the Hybrid IVUS-OCT Imaging System. JACC Asia 2025, 5, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, A.; LaCombe, A.; Stickland, A.; Madder, R.D. Intracoronary Near-Infrared Spectroscopy: An Overview of the Technology, Histologic Validation, and Clinical Applications. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2016, 2016, e201618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kook, H.; Park, S.; Heo, R.; Park, J.-K.; Shin, J.; Lee, Y.; Lim, Y.-H. Impact of Post-PCI Lipid Core Burden Index on Angiographic and Clinical Outcomes: Insights From NIRS-IVUS. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yang, F.; Kumar, S.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Tu, S. Intravascular Imaging for Acute Coronary Syndrome. NPJ Cardiovasc. Health 2025, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, C.; Sotomi, Y.; Cavalcante, R.; Suwannasom, P.; Tenekecioglu, E.; Onuma, Y.; Serruys, P.W. Coronary Stent Thrombosis: What Have We Learned? J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ino, Y.; Kubo, T.; Matsuo, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Shiono, Y.; Shimamura, K.; Katayama, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Aoki, H.; Taruya, A.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Predictors for Edge Restenosis After Everolimus-Eluting Stent Implantation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, L.N.; Neghabat, O.; Laanmets, P.; Kumsars, I.; Bennett, J.; Olsen, N.T.; Odenstedt, J.; Burzotta, F.; Johnson, T.W.; O’Kane, P.; et al. Unintended Deformation of Stents During Bifurcation PCI: An OCTOBER Trial Substudy. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmesser, U.; Ali, Z.A.; Maehara, A.; Matsumura, M.; Shlofmitz, R.A.; Guagliumi, G.; Price, M.J.; Hill, J.M.; Akasaka, T.; Prati, F.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Predictors of Clinical Outcomes after Stent Implantation: The ILUMIEN IV Trial. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 4630–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, A.W.; Hodgson, J.M.; Müller, C.; Bestehorn, H.P.; Roskamm, H. Ultrasound-Guided Strategy for Provisional Stenting with Focal Balloon Combination Catheter: Results from the Randomized Strategy for Intracoronary Ultrasound-Guided PTCA and Stenting (SIPS) Trial. Circulation 2000, 102, 2497–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiele, F.; Meneveau, N.; Vuillemenot, A.; Zhang, D.D.; Gupta, S.; Mercier, M.; Danchin, N.; Bertrand, B.; Bassand, J.P. Impact of Intravascular Ultrasound Guidance in Stent Deployment on 6-Month Restenosis Rate: A Multicenter, Randomized Study Comparing Two Strategies—With and without Intravascular Ultrasound Guidance. RESIST Study Group. REStenosis after Ivus Guided STenting. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998, 32, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.-J.; Kim, B.-K.; Shin, D.-H.; Nam, C.-M.; Kim, J.-S.; Ko, Y.-G.; Choi, D.; Kang, T.-S.; Kang, W.-C.; Her, A.-Y.; et al. Effect of Intravascular Ultrasound-Guided vs Angiography-Guided Everolimus-Eluting Stent Implantation: The IVUS-XPL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015, 314, 2155–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, X.; Kan, J.; Ge, Z.; Han, L.; Lu, S.; Tian, N.; Lin, S.; Lu, Q.; Wu, X.; et al. Intravascular Ultrasound Versus Angiography-Guided Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation: The ULTIMATE Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 3126–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.-K.; Shin, D.-H.; Hong, M.-K.; Park, H.S.; Rha, S.-W.; Mintz, G.S.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, H.-Y.; et al. Clinical Impact of Intravascular Ultrasound–Guided Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention with Zotarolimus-Eluting Versus Biolimus-Eluting Stent Implantation: Randomized Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzenbichler, B.; Maehara, A.; Weisz, G.; Neumann, F.-J.; Rinaldi, M.J.; Metzger, D.C.; Henry, T.D.; Cox, D.A.; Duffy, P.L.; Brodie, B.R.; et al. Relationship between Intravascular Ultrasound Guidance and Clinical Outcomes after Drug-Eluting Stents: The Assessment of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy with Drug-Eluting Stents (ADAPT-DES) Study. Circulation 2014, 129, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A.; Maehara, A.; Généreux, P.; Shlofmitz, R.A.; Fabbiocchi, F.; Nazif, T.M.; Guagliumi, G.; Meraj, P.M.; Alfonso, F.; Samady, H.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Compared with Intravascular Ultrasound and with Angiography to Guide Coronary Stent Implantation (ILUMIEN III: OPTIMIZE PCI): A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2016, 388, 2618–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otake, H.; Kubo, T.; Takahashi, H.; Shinke, T.; Okamura, T.; Hibi, K.; Nakazawa, G.; Morino, Y.; Shite, J.; Fusazaki, T.; et al. Optical Frequency Domain Imaging Versus Intravascular Ultrasound in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (OPINION Trial): Results From the OPINION Imaging Study. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, H.I.; Elgendy, M.S.; Shubietah, A.; Amin, A.M.; Ezz, M.R.; Ghazal, A.M.; ElShanat, M.A.; Zayan, H.; Tolba, K.; Abuelazm, M.; et al. Optical Frequency Domain Imaging versus Intravascular Ultrasound for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Coron. Artery Dis. 2025, 36, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.; Hong, D.; Choi, K.H.; Lee, S.H.; Shin, D.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.M.; Yun, K.H.; et al. Intravascular Imaging-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Before and After Standardized Optimization Protocols. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, Y.; Leipsic, J.A.; Collet, C.; Ali, Z.A.; Azzalini, L.; Barbato, E.; Cavalcante, J.L.; Costa, R.A.; Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; Jones, D.A.; et al. Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography to Guide Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Expert Opinion from a SCAI/SCCT Roundtable. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2025, 4, 103664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, E.J.; Mesenbring, E.; Smith, T.; Hebbe, A.; Salahuddin, T.; Waldo, S.W.; Dyal, M.D.; Doll, J.A. Intravascular Imaging as a Performance Measure for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2025, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenogiannis, I.; Pavlidis, A.N.; Kaier, T.E.; Rigopoulos, A.G.; Karamasis, G.V.; Triantafyllis, A.S.; Vardas, P.; Brilakis, E.S.; Kalogeropoulos, A.S. The Role of Intravascular Imaging in Chronic Total Occlusion Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1199067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegere, S.; Narbute, I.; Erglis, A. Use of Intravascular Imaging in Managing Coronary Artery Disease. World J. Cardiol. 2014, 6, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, M.; Adedokun, S.; Narayanan, M.A. Role of Intravascular Ultrasound and Optical Coherence Tomography in Intracoronary Imaging for Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. JGC 2024, 21, 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, G.S. Intravascular Imaging for PCI. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, R.; Yeh, R.W.; Cohen, D.J.; Rao, S.V.; Li, S.; Song, Y.; Secemsky, E.A. Intravascular Imaging during Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Temporal Trends and Clinical Outcomes in the USA. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3845–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Cho, J.; Guallar, E.; Choi, K.H.; Lee, S.H.; Shin, D.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Intravascular Imaging-Guided Complex PCI: Prespecified Analysis of RENOVATE-COMPLEX-PCI Trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 17, e010230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Hong, S.J.; Kim, H.-S.; Yoon, Y.W.; Lee, J.-Y.; Oh, S.-J.; Lee, J.S.; Kang, S.-J.; Kim, Y.-H.; Park, S.-W.; et al. Quantitative Coronary Angiography vs Intravascular Ultrasonography to Guide Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otake, H.; Kubo, T.; Hibi, K.; Natsumeda, M.; Ishida, M.; Kataoka, T.; Takaya, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Sonoda, S.; Shinke, T.; et al. Optical Frequency Domain Imaging-Guided versus Intravascular Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Coronary Syndromes: The OPINION ACS Randomised Trial. EuroIntervention 2024, 20, e1086–e1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwańczyk, S.; Woźniak, P.; Araszkiewicz, A.; Grygier, M.; Klotzka, A.; Lesiak, M. Optical Coherence Tomography in the Diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries. Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2022, 18, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.; Sami, Z.; Cannata, M.; Ciftcikal, Y.; Caron, E.; Thomas, S.V.; Porter, C.R.; Tsioulias, A.; Gujja, M.; Sakai, K.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Intravascular Imaging for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions: A New Era of Precision. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2025, 4, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T.; Theodoropoulos, K.; Latib, A.; Okura, H.; Kobayashi, Y. Coronary Physiologic Assessment Based on Angiography and Intracoronary Imaging. J. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiba, T.; Aizawa, K.; Ho, M.; Ishii, K. Regulatory Review of Robotic-Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Japan. Circ. J. 2024, 88, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlofmitz, E.; Torguson, R.; Mintz, G.S.; Zhang, C.; Sharp, A.; Hodgson, J.M.; Shah, B.; Kumar, G.; Singh, J.; Inderbitzen, B.; et al. The IMPact on Revascularization Outcomes of intraVascular Ultrasound-Guided Treatment of Complex Lesions and Economic Impact (IMPROVE) Trial: Study Design and Rationale. Am. Heart J. 2020, 228, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | OCT A | IVUS B | NIRS C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Source | Near-infrared light | Ultrasound (20–60 MHz) | Near-infrared light |

| Wavelength (µm) | 1.3 | 35–80 | 800–2500 |

| Resolution (µm) | 15–20 (axial); 20–40 (lateral) | 100–200 (axial); 200–300 (lateral) | Low (not intended for morphological resolution) |

| Frame Rate (Frames/S) | 15–20 | 30 | N/A |

| Pull-Back Rate (mm/S) | 1–3 | 0.5–1 | 0.5–1 |

| Maximum Scan Diameter (mm) | 7 | 15 | 15 |

| Tissue Penetration (mm) | 1–2.5 | 10 | 1–1.5 |

| Blood Clearing | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Advantages | Can measure and characterize thickness of calcium | More favorable imaging in larger vascular structures (e.g., left main) | Detects lipid-core plaques; quantifies lipid burden (Lipid Core Burden Index) |

| Disadvantages | Cannot accurately assess residual plaque burden at stent edges | Inferior detection of stent malapposition and edge dissections | Cannot visualize lumen or stent apposition; low spatial resolution |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alqawasmi, M.; Blankenship, J.C. Intravascular Imaging-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Transforming Precision and Outcomes in Contemporary Practice. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8883. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248883

Alqawasmi M, Blankenship JC. Intravascular Imaging-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Transforming Precision and Outcomes in Contemporary Practice. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8883. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248883

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqawasmi, Malik, and James C. Blankenship. 2025. "Intravascular Imaging-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Transforming Precision and Outcomes in Contemporary Practice" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8883. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248883

APA StyleAlqawasmi, M., & Blankenship, J. C. (2025). Intravascular Imaging-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Transforming Precision and Outcomes in Contemporary Practice. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8883. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248883