Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): New Perspectives on an Evolving Epidemic

Abstract

1. Historical Perspective

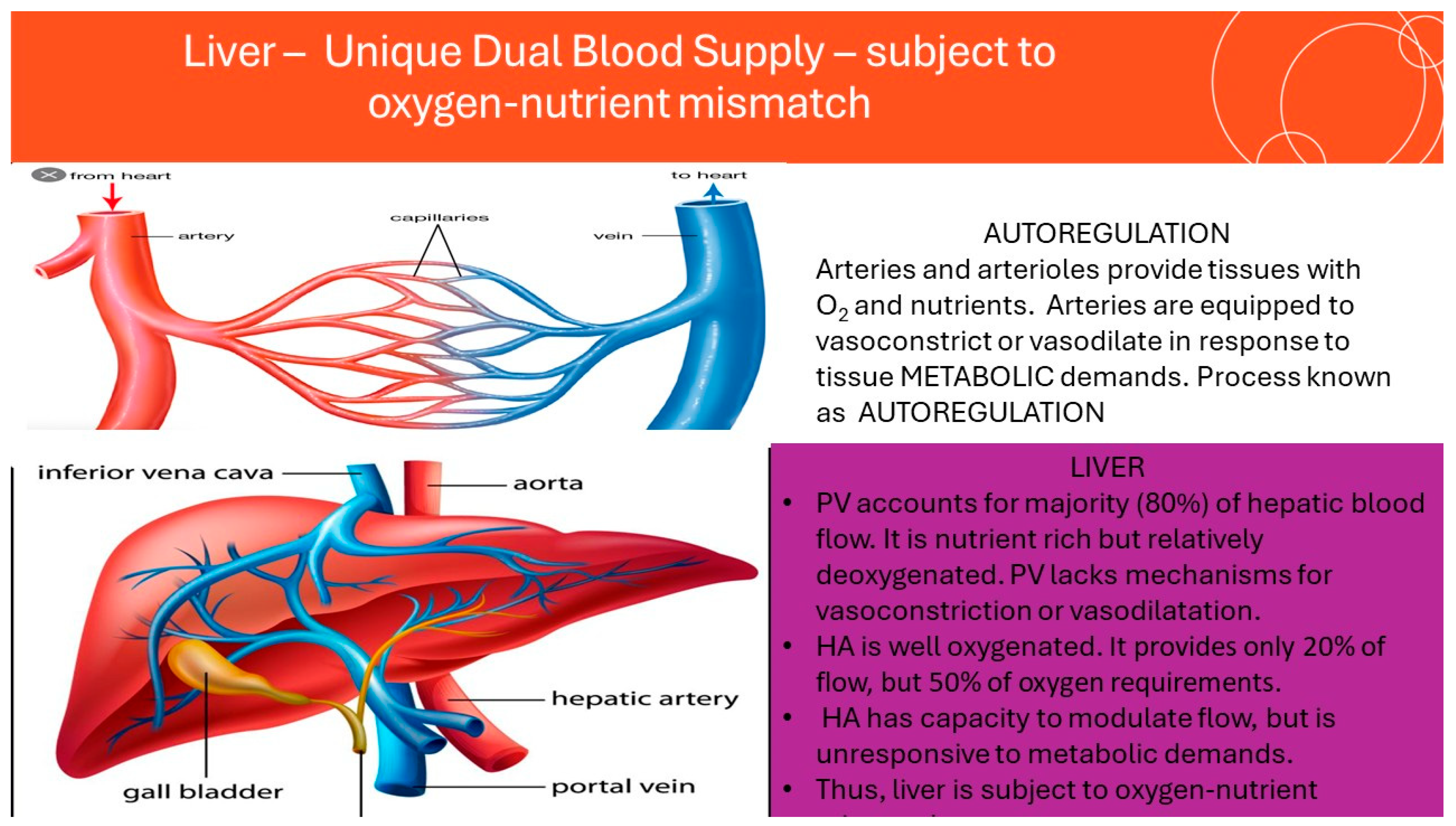

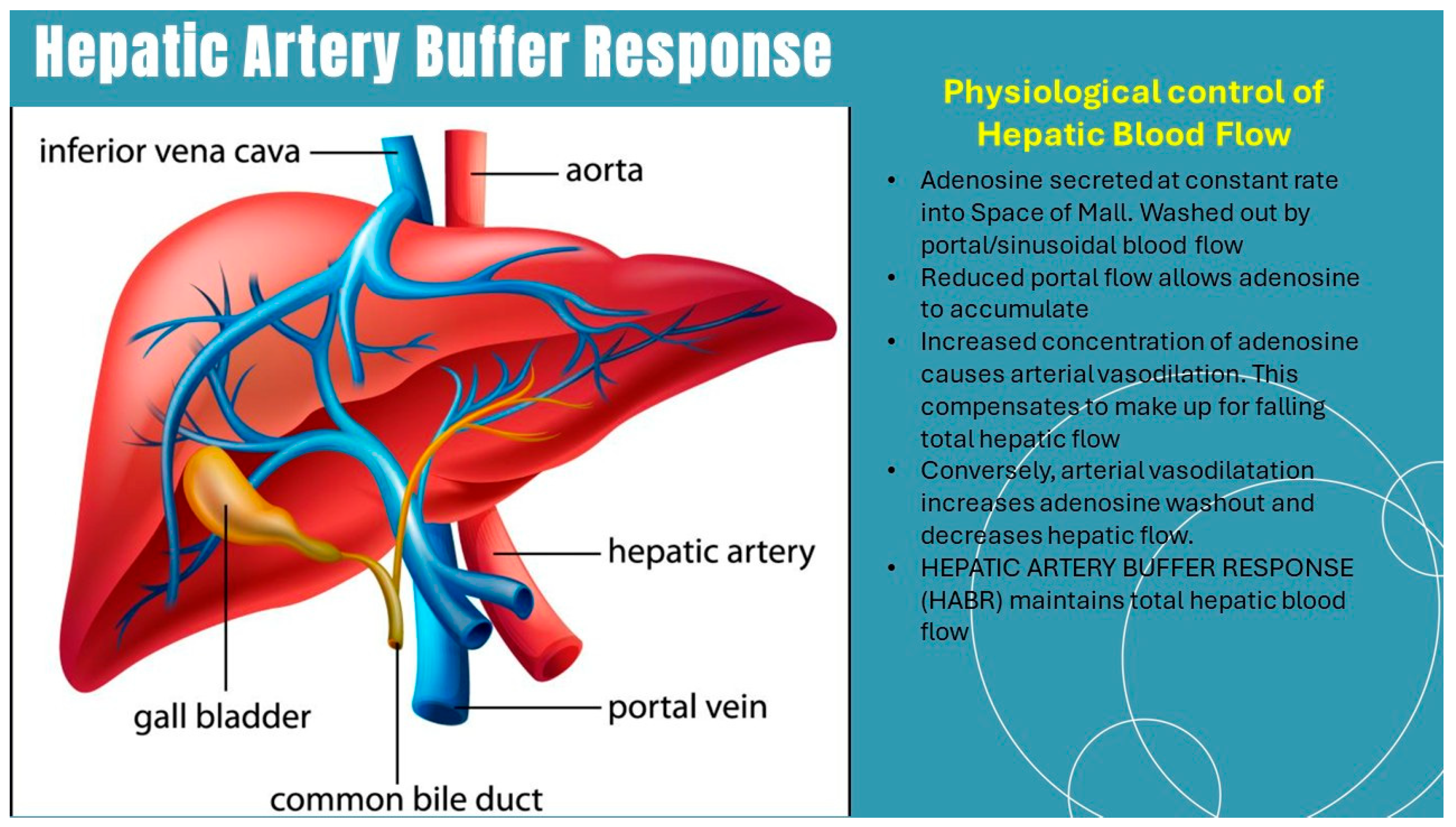

2. Caloric Intake in ALD and MASLD

3. The Concept of Oxygen-Nutrient Mismatch in ALD and MASLD

4. How Ethanol Metabolism Differs from Macronutrient Metabolism in the Liver

5. Treatment of MASLD Based on Re-Balancing the Oxygen-Nutrient Equation

Diet, Exercise

6. Effect of Weight Loss Medications

7. Influence of Drugs Modulating Hepatic Blood Flow

8. Potential Impact of Non-Selective Beta-Blockers

9. Enhancing Hepatic Basal Metabolism

10. Conclusions

11. Directions for Future Research

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ludwig, J.; Viggiano, T.R.; McGill, D.B.; Oh, B.J. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1980, 55, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, F.; Thaler, H. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Prog. Liver Dis. 1986, 8, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saadeh, S.; Younossi, Z.M. The spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2000, 67, 96–97, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake-Bakaar, G. Alcohol and the Liver; Nova Biomedical: Waltham, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Canivet, C.M.; Boursier, J.; Loomba, R. New Nomenclature for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Understanding Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease, Metabolic Dysfunction- and Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease, and Their Implications in Clinical Practice. Semin. Liver. Dis. 2024, 44, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, A.; Tiniakos, D.; Denk, H.; Trauner, M. From the origin of NASH to the future of metabolic fatty liver disease. Gut 2021, 70, 1570–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.C. Autoregulation of blood flow. Circ. Res. 1986, 59, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezai, S.; Sakurabayashi, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Morita, T.; Hirano, M.; Oka, H. Hepatic arterial and portal venous oxygen content and extraction in liver cirrhosis. Liver 1993, 13, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton-Opitz, R. The vascularity of the liver: The influence of the portal blood flow upon the flow in the hepatic artery. Quart. J. Exp. Physiol. Cogn. Med. Sci. 1911, 4, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautt, W.W. Control of hepatic arterial blood flow: Independence from liver metabolic activity. Am. J. Physiol. 1980, 239, H559–H564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautt, W.W. Role and Control of the Hepatic Artery. Hepatic Circulation in Health and Disease; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lautt, W.W. The 1995 Ciba-Geigy Award Lecture. Intrinsic regulation of hepatic blood flow. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1996, 74, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautt, W.W. Mechanism and role of intrinsic regulation of hepatic arterial blood flow: Hepatic arterial buffer response. Am. J. Physiol. 1985, 249, G549–G556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake-Bakaar, G.; Robertson, J.; Aardema, C. The effect of obeticholic acid on hepatic blood flow in isolated, perfused porcine liver: Correction of oxygen-nutrient mismatch might be a putative mechanism of action in NASH. Clin. Transl. Discov. 2022, 2, e98. [Google Scholar]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Minville, C.; Tordjman, J.; Levy, P.; Bouillot, J.L.; Basdevant, A.; Bedossa, P.; Clement, K.; Pepin, J.L. Chronic intermittent hypoxia is a major trigger for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in morbid obese. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Clement, K.; Pepin, J.L. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obstructive sleep apnea. Metabolism 2016, 65, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Pepin, J.L. New insights in the pathophysiology of chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced NASH: The role of gut-liver axis impairment. Thorax 2015, 70, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, E.A.; El-Badry, A.M.; Mocchegiani, F.; Montalti, R.; Hassan, A.E.A.; Redwan, A.A.; Vivarelli, M. Impact of Graft Steatosis on Postoperative Complications after Liver Transplantation. Surg. J. 2018, 4, e188–e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drager, L.F.; Li, J.; Reinke, C.; Bevans-Fonti, S.; Jun, J.C.; Polotsky, V.Y. Intermittent hypoxia exacerbates metabolic effects of diet-induced obesity. Obesity 2011, 19, 2167–2174. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine, M.; Serfaty, L. Chronic intermittent hypoxia: A breath of fresh air in the understanding of NAFLD pathogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Miao, Y.; Wu, F.; Du, T.; Zhang, Q. Effect of CPAP therapy on liver disease in patients with OSA: A review. Sleep Breath. 2018, 22, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesarwi, O.A.; Loomba, R.; Malhotra, A. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Hypoxia, and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, G.; Olivetti, C.; Cassader, M.; Gambino, R. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Emerging evidence and mechanisms. Semin. Liver Dis. 2012, 32, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajantri, B.; Lvovsky, D. A Case of Concomitant Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis Treated With CPAP Therapy. Gastroenterol. Res. 2018, 11, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Ahmed, A.; Kushida, C. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, S.S.; Halbower, A.C.; Klawitter, J.; Pan, Z.; Robbins, K.; Capocelli, K.E.; Sokol, R.J. Treating Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia Improves the Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children. J. Pediatr. 2018, 198, 67–75.e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Wang, H.; Han, X.; Liu, H.; Zhu, D.; Feng, W.; Wu, J.; Bi, Y. Oxygen therapy alleviates hepatic steatosis by inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 246, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuele, F.; Biondo, M.; Tomasello, L.; Arnaldi, G.; Guarnotta, V. Ketogenic Diet in Steatotic Liver Disease: A Metabolic Approach to Hepatic Health. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.F.; Varady, K.A.; Wang, X.D.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tayyem, R.; Latella, G.; Bergheim, I.; Valenzuela, R.; George, J.; et al. The role of dietary modification in the prevention and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international multidisciplinary expert consensus. Metabolism 2024, 161, 156028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, K.; Michael Trauner, M.; Bergheim, I. Pathogenic aspects of fructose consumption in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): A narrative review. Cell Stress 2025, 9, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Prough, R.A.; McClain, C.J.; Song, M. Different Types of Dietary Fat and Fructose Interactions Result in Distinct Metabolic Phenotypes in Male Mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 111, 109189. [Google Scholar]

- Yki-Jarvinen, H.; Luukkonen, P.K.; Hodson, L.; Moore, J.B. Dietary carbohydrates and fats in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 770–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.; Monserrat-Mesquida, M.; Ugarriza, L.; Casares, M.; Gomez, C.; Mateos, D.; Angullo-Martinez, E.; Tur, J.A.; Bouzas, C. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Metabolic-Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Longitudinal and Sustainable Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geladari, E.V.; Kounatidis, D.; Christodoulatos, G.S.; Psallida, S.; Pavlou, A.; Geladari, C.V.; Sevastianos, V.; Dalamaga, M.; Vallianou, N.G. Ultra-Processed Foods and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): What Is the Evidence So Far? Nutrients 2025, 17, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Qiao, W.; Zhuang, J.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Association of ultra-processed food intake with severe non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A prospective study of 143073 UK Biobank participants. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2024, 28, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, V.A.; Cabezas, M.C.; Hernandez Vargas, J.A.; Trujillo-Caceres, S.J.; Mendez Pernicone, N.; Bridge, L.A.; Raeisi-Dehkordi, H.; Dietvorst, C.A.W.; Dekker, R.; Uriza-Pinzon, J.P.; et al. Effects of Mediterranean diet, exercise, and their combination on body composition and liver outcomes in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channapragada, T.; Batra, S.; Hummer, B.L.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Huang, D.; Loomba, R.; Schreibman, I.R.; Stine, J.G. Aerobic Exercise Training Leads to MASH Resolution as Defined by the MASH Resolution Index. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2025, 70, 4209–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Nie, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Shao, B. Exercise ameliorates hepatic lipid accumulation via upregulating serum PRL and activating hepatic PRLR-mediated JAK2/STAT5 signaling pathway in NAFLD mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1647231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Meng, Q.; Wu, P. Effects of Weight Loss on Insulin Resistance and Liver Health in T2DM and NAFLD Patients. Med. Sci. Monit. 2025, 31, e947157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Sohal, A.; Noureddin, M.; Kowdley, K.V. Resmetirom: The first approved therapy for treating metabolic dysfunction associated steatohepatitis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2025, 26, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. MASLD Pharmacotherapy: Current Standards, Emerging Treatments, and Practical Guidance for Indian Physicians. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2025, 73, e45–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concepcion-Zavaleta, M.J.; Fuentes-Mendoza, J.M.; Gonzales-Yovera, J.G.; Ruvalcaba-Barbosa, G.Y.; Cura-Rodriguez, L.D.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.S.; Concepcion-Urteaga, L.A.; Perez-Reyes, A.I.; Quiroz-Aldave, J.E.; Paz-Ibarra, J. Efficacy and safety of anti-obesity drugs in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: An updated review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 111435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, N.; Hartmann, P. Antiobesity medications in adult and pediatric obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2025, 77, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somabattini, R.A.; Sherin, S.; Siva, B.; Chowdhury, N.; Nanjappan, S.K. Unravelling the complexities of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: The role of metabolism, transporters, and herb-drug interactions. Life Sci. 2024, 351, 122806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suffert, L.C.; Beis, L.P.P.; Padilha, I.H.; de Abreu, H.S.; de Souza, J.S.; Galvao, V.A.; Friedrich, F.; da Silva, M.C.A. Propranolol versus endoscopic variceal ligation for primary prophylaxis of esophageal varices in cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hepatol. Int. 2025, 19, 1162–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurohit, S.; Musunuri, B.; Basthi Mohan, P.; Bhat, G.; Shetty, S. Is carvedilol superior to propranolol in patients with cirrhosis with portal hypertension: A systematic and meta-analysis. Drugs Context 2025, 14, 2024-11-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, R.I.; Minea, H.O.; Huiban, L.; Damian, I.R.; Muset, M.C.; Juncu, S.; Muzica, C.M.; Zenovia, S.; Singeap, A.M.; Girleanu, I.; et al. Advancements in Beta-Adrenergic Therapy and Novel Personalised Approach for Portal Hypertension: A Narrative Review. Life 2025, 15, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almenara, S.; Lozano-Ruiz, B.; Herrera, I.; Gimenez, P.; Miralles, C.; Bellot, P.; Rodriguez, M.; Palazon, J.M.; Tarin, F.; Sarmiento, H.; et al. Immune changes over time and survival in patients with cirrhosis treated with non-selective beta-blockers: A prospective longitudinal study. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, H.R.; Chuah, C.S.; Tripathi, D.; Stanley, A.J.; Forrest, E.H.; Hayes, P.C. Carvedilol is associated with improved survival in patients with cirrhosis: A long-term follow-up study. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 53, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hones, G.S.; Sivakumar, R.G.; Hoppe, C.; Konig, J.; Fuhrer, D.; Moeller, L.C. Cell-Specific Transport and Thyroid Hormone Receptor Isoform Selectivity Account for Hepatocyte-Targeted Thyromimetic Action of MGL-3196. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, A.M.; Mahmoud, M.; AlShuraiaan, G.M. Resmetirom: The First Disease-Specific Treatment for MASH. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 2025, 6430023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, F.; Elshaer, A.; Odeh, N.B.; Alatout, M.H.; Shahin, T.; Worden, A.R.; Albunni, H.N.; Lizaola-Mayo, B.C.; Jayasekera, C.R.; Chascsa, D.M.H.; et al. Resmetirom in the Management of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Steatohepatitis. Life 2025, 15, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Gu, Y.; Hu, L.; Qu, H.; Li, N.; Xia, C.; Feng, L.; Qin, L.; Hai, L.; Yang, Y.; et al. Discovery of Highly Potent, Selective, and Liver-Targeted THR-beta Agonists for the Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 17457–17472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.H.; Zeng, Q.M.; Hu, T.Y.; Huang, Y.; Song, Y.; Guan, H.; Rockey, D.C.; Tang, H.; Li, S. Resmetirom and thyroid hormone receptor-targeted treatment for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Portal Hypertens. Cirrhosis 2025, 4, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venediktova, N.; Khmil, N.; Pavlik, L.; Mikheeva, I.; Mironova, G. Pathological Changes in Liver Mitochondria of Rats with Experimentally Induced Hyperthyroidism and Their Correction with Uridine. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 83, 5217–5226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, L.; Shaukat, A.; Akilimali, A. Resmetirom: A Breakthrough in the Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupland, B.R.; Laupland, K.; Thistlethwaite, K.; Webb, R. Contemporary practices of blood glucose management in diabetic patients: A survey of hyperbaric medicine units in Australia and New Zealand. Diving Hyperb. Med. 2023, 53, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lake-Bakaar, G. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): New Perspectives on an Evolving Epidemic. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248872

Lake-Bakaar G. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): New Perspectives on an Evolving Epidemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248872

Chicago/Turabian StyleLake-Bakaar, Gerond. 2025. "Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): New Perspectives on an Evolving Epidemic" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248872

APA StyleLake-Bakaar, G. (2025). Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): New Perspectives on an Evolving Epidemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248872