1. Introduction

Osteoporosis, the most common metabolic bone disease, affects more than 50 million adults over age 50 in the United States and approximately 200 million worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. With the aging population, its prevalence is projected to rise by about 33% by 2030 [

1]. As osteoporosis becomes more common, so too will spine fractures and the number of osteoporotic patients who may be candidates for spine surgery, particularly spinal fusions. The prevalence of low bone density among spine surgery candidates is substantial: several reports indicate that over 30% have osteoporosis and more than 45% have osteopenia [

4,

5], and one study found that over 50% of women and nearly 14.5% of men older than 50 undergoing spine surgery met the criteria for osteoporosis [

6].

Compromised bone density negatively impacts the clinical success of fixation-dependent procedures, such as fusions, and increases healthcare costs. Because both instrumentation and capacity to form a solid fusion relies on patient bone density, osteoporosis adversely affects outcomes [

7] and is associated with greater difficulty with instrumentation and fixation, along with higher rates of postoperative complications, including pseudoarthrosis, spinal fracture, blood loss, and hardware failure [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. An analysis using the National Inpatient Sample found that osteoporotic patients undergoing cervical spine surgery had a 1.5-times greater chance of requiring revision surgeries and 30% higher hospitalization costs [

15]. In patients undergoing primary posterior thoracolumbar or lumbar fusion, pseudoarthrosis occurred in 46.2% of those with osteoporosis [

8].

Despite evidence that poor bone health worsens spine surgery outcomes, routine screening and treatment for osteoporosis remain inconsistent among spine surgery patients [

16], revealing a care gap and an opportunity for bone health optimization. Bone Health Clinics (BHCs) and Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) are designed to close this gap by improving identification, initiating evidence-based therapy, and follow-up care focused on osteoporosis management [

17]. These programs have been shown to increase treatment rates following a fracture, reduce the rate of secondary fractures, and may lower healthcare costs [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

The purpose of this study is to describe a multidisciplinary approach at a single academic institution using a newly created BHC housed within the orthopedic trauma department. This BHC represents a novel clinic started and run by advanced practice providers specifically focused on evaluating and optimizing the bone density of orthopedic and neurosurgical patients with fragility fractures or upcoming surgeries. We evaluated patient demographics, surgical characteristics, pharmacologic management, decision-making, and postoperative and clinical outcomes. We hypothesized that integrating a dedicated bone health service into perioperative spine care would be feasible, increase treatment initiation, and be associated with favorable early surgical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Patient Population

We retrospectively reviewed 174 perioperative patients referred to the BHC between October 2019 and April 2024 for spine-related indications. Patients were advised for referral based on predefined internal Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guidelines that aim to identify high-risk spine fusion candidates whose bone health needed optimization [

19,

24]. These criteria, as detailed in

Table 1, include clinical risk factors, any prior bone mineral density assessment, and multidisciplinary evaluations. Specific numeric thresholds for malnutrition were not uniformly imposed across all referring surgeons. Clinician documentation often reflected consideration of BMI, unintentional weight loss, and/or laboratory parameters (e.g., low albumin) [

25,

26]. Low CT Hounsfield units (HU) were coded when the evaluating surgeon and/or radiologist documented subthreshold trabecular HU on preoperative lumbar CT, excluding areas with focal degenerative sclerosis. While thresholds vary in practice, the literature supports HU < 110 as suggestive of osteoporosis [

27,

28]. A discussion of these criteria was facilitated by BHC staff with all attending spine surgeons at our institution. The referral workflow was multidisciplinary and typically initiated by the attending spine surgeon (Neurosurgery or Orthopedic Surgery) when a patient met these high-risk criteria. When placing a referral, the surgical team ordered a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan and labs as detailed in the data collection section. Following the surgeon’s referral trigger, the patient underwent standardized evaluation by a dedicated advanced practice provider (APP) within the BHC for comprehensive metabolic bone disease workup and optimization prior to or immediately following surgery.

Our perioperative cohort included patients referred to the BHC who had undergone spine fusion prior to their visit or those referred for optimization prior to a future spine surgery. Patients were included in this study if they had been formally evaluated through the BHC and received pre- and postoperative surgical follow-up. Referral patterns reflected the multidisciplinary integration of the service, with most patients referred from surgical specialties, particularly neurosurgery and orthopedics. The BHC protocol involves comprehensive screening, diagnosis, and initiation of pharmacotherapy. Patients who were identified as having complex or high-risk secondary causes of osteoporosis were referred to specialized services for co-management. This included direct referral to endocrinology services for individuals with suspected or confirmed diagnoses such as uncontrolled hyperparathyroidism, new or complicated Cushing’s syndrome, male hypogonadism requiring specialized therapy, or other complex metabolic or endocrine derangements that fall outside the scope of BHC management. Overall, this cohort represents a consecutive series of patients undergoing standardized evaluation and management at a single-institution bone health optimization program.

2.2. Bone Health Diagnosis

Bone health diagnoses were established in accordance with American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF) guidelines [

29,

30]. Osteoporosis was defined as a T-score ≤ −2.5 at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, or total hip or the presence of a low-energy fragility fracture of the hip or spine regardless of bone mineral density (BMD). Osteopenia was defined as a T-score between −1.0 and −2.4. A diagnosis of osteoporosis was also given to patients in the osteopenia range who had a history of fragility fracture at any site, consistent with guideline-based practice. The lowest T-score across any site (lumbar spine, femoral neck, or total hip) was used for our primary analysis. This is due to local factors such as spine degenerative changes, presence of hardware, or prior fractures that may lead to falsely elevated BMD scores at the lumbar spine and mask systemic osteoporosis.

2.3. Data Collection

A retrospective review of the electronic medical record (Epic, Epic Systems, version May 2025) was performed for all eligible patients. Demographic variables collected included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), race and ethnicity, and health insurance status. Surgical variables included surgical indication, procedure and surgical approach, number of spinal levels fused, hardware failure (screw loosening, pullout, breakage, rod failure), and the length of surgical follow-up. Bone health assessments included DXA scans of the lumbar spine, femur, and distal radius. Laboratory studies obtained at or before the first BHC visit were also collected, including serum calcium, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, albumin, parathyroid hormone (PTH), C-terminal telopeptide (CTx), procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP), and phosphorus. At their first BHC visit, patients completed a structured intake questionnaire documenting established risk factors for osteoporosis and fracture (

Table 2). This included history of prior fragility fractures, family history of osteoporosis or hip fracture, history of falls, height loss, current or prior smoking history, alcohol and caffeine use, exercise habits, and dietary practices such as vegetarianism or veganism. The questionnaire also captured relevant medical comorbidities including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, celiac disease, chronic kidney disease, seizure disorder, HIV/AIDS, gastric bypass, hepatitis B or C, COPD, Paget’s disease, hyperparathyroidism, diabetes, history of cancer, and/or long-term steroid use. Information on medication exposure was recorded for agents known to affect bone health, including bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, zoledronate, pamidronate), PTH analogues (teriparatide, abaloparatide), romosozumab, denosumab, calcitonin, raloxifene, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), oral glucocorticoids, anticonvulsants, opioids, anticoagulants, and hormone replacement therapy. Nutritional supplementation with calcium and vitamin D was also documented.

2.4. Surgical Outcomes and Diagnostic Criteria

Surgical outcomes, including rates of hardware failure (screw loosening, pullout, breakage, rod failure) and subsequent revision surgery, were retrospectively assessed via comprehensive electronic medical record review. The diagnosis of hardware failure was determined based on objective radiologic criteria seen on plain radiographs and/or CT scans.

Postoperative surveillance routinely included X-rays obtained at fixed time points, typically 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. If these X-rays revealed concerning findings (e.g., progressive lucency, hardware migration) or if the patients presented with clinical complaints (e.g., increasing pain or neurological symptoms), a CT scan was performed to further work up and confirm hardware failure. Specifically, screw loosening/pullout was defined as a lucency (halo) greater than 1 mm surrounding the screw threads or documented progressive screw migration on postoperative imaging. Screw or rod breakage and failure was confirmed by demonstrating complete hardware discontinuity on imaging. Interbody subsidence was defined as vertical migration or collapse of the interbody device into adjacent vertebral endplates, as measured radiographically or requiring surgical revision.

Treatment-related data included the first medication prescribed, sequencing of subsequent therapies, contraindications, patient preference, prior osteoporosis treatment, insurance-related barriers, and duration of therapy relative to surgery. All data were stored in REDCap (version 15.8.0) hosted at Stanford University. The study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (Project 59326).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of categorical variables were conducted using chi-squared tests. Graphs were produced using version 10 of GraphPad Prism. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, and all tests used were two-sided. All statistical and graphical analyses were conducted using version 4.3.2 of the R program language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and Microsoft Excel.

4. Discussion

Our institution developed a Bone Health Clinic housed in the orthopedic trauma department in 2019 for fragility fracture and metabolic bone disease, focused on identifying risks, investigating causes, and implementing treatment plans to reduce the risk of future fractures and optimize surgical outcomes. The clinical philosophy driving the BHC emphasizes the long-term management of osteoporosis as a chronic systemic disease. The clinic operates at the intersection of neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, endocrinology, and rheumatology. In this study, we describe our approach to perioperative bone optimization for spinal fusions. Spine surgery (and spinal fusion in particular) is challenging in the elderly due to a high prevalence of poor bone quality [

33,

34,

35]. Osteoporotic patients undergoing spinal fusion face increased perioperative complications, including vertebral fractures after instrumentation, pseudoarthrosis, estimated blood loss, and hardware failures [

9,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. They are also more likely to require revision surgery, have longer hospitalizations, and incur higher inpatient and outpatient costs compared to non-osteoporotic patients. Given these risks, perioperative bone optimization may be beneficial for successful outcomes [

15,

42,

43].

More than 70% of patients referred to the clinic for spine surgery bone optimization received an osteoporosis diagnosis, with an additional 47% diagnosed with osteopenia, underscoring the high prevalence of poor bone quality in this population. Because the average T-score among those diagnosed with osteoporosis was −2.3, we examined patients with an osteoporosis diagnosis despite osteopenia-range DXA scores. Nearly 94% of this subset had prior fragility fractures. Consistent with diagnostic criteria, a documented low-energy fracture (e.g., hip or vertebral) supersedes screening tools such as DXA and should prompt treatment and perioperative optimization. Accordingly, fracture history was prioritized over densitometric thresholds when making therapeutic decisions in this cohort. The remainder were diagnosed by another provider prior to starting treatment at the BHC or due to poor bone quality found intraoperatively. Thus, a substantial proportion of patients carry an osteoporosis diagnosis based on fragility fractures rather than densitometric criteria alone, a critical consideration for treatment decisions. Notably, a previous study found that only 25.6% of patients with primary fragility fractures had received a DXA scan or initiated pharmacotherapy in the two years before the fracture [

44].

Nearly 52% of patients started treatment at the BHC preoperatively, with a mean lead time of 8 months prior to surgery, consistent with current clinical practice [

45,

46]. Although surgery was delayed for these patients, they were generally motivated to optimize their bone health and expressed appreciation for referral. Following comprehensive evaluation, patients with evidence of poor bone health were commonly prescribed medications. Overall, 84% received first-line pharmacotherapy, guided by initial labs, screening for comorbidities and contraindications, and the 2020 AACE Clinical Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis [

30]. This approach targeted patients for drug interventions who were classified as “high-risk” based on clinical factors beyond BMD alone, including those with a recent or multiple fragility fractures (within the last 12 months), fracture occurrence while on approved osteoporosis therapy or while taking long-term corticosteroids, a low T-score (≤−3.0) at the spine, femoral neck, or total hip, a high risk for falls, or a very high FRAX

® probability (>30% for major osteoporotic fracture or >4.5% for hip fracture).

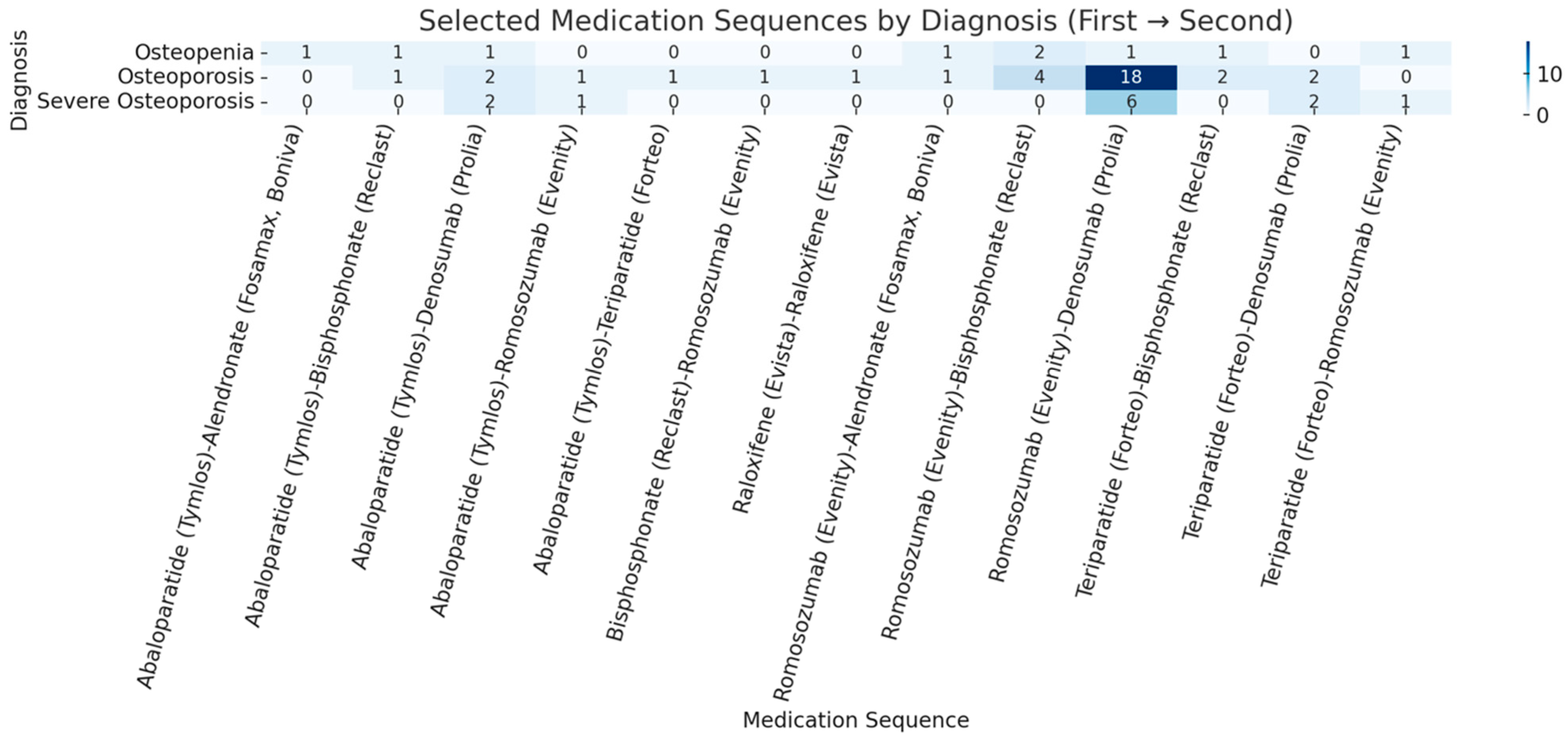

The AACE guidelines recommend anabolic agents first: these include teriparatide, ababaloparatide, or romosozumab. This is why our BHC protocol involves an anabolic-first approach, aimed at sequential therapies to promote rapid and robust bone quality improvement in this high-risk surgical population; 77% of those treated were placed on anabolic agents (romosozumab, abaloparatide, and teriparatide). If the first-line anabolic agents were contraindicated or if patients were unable to obtain insurance coverage, antiresorptive agents, such as denosumab, were considered as a secondary option based off results from this 2016 study [

47]. This approach, while distinct from traditional osteoporosis treatment pathways, reflects the current standard of care for our high-risk patient population [

40]. Patients undergoing spine fusion surgery, particularly those with existing osteoporosis or recent fragility fractures, are considered to be at high risk, necessitating rapid and robust bone quality improvement [

48]. Anabolic agents are increasingly favored perioperatively because they promote bone formation, improve bone mass and architecture, and reduce fracture risk more than traditional antiresorptives [

49,

50,

51].

Teriparatide consistently reduces vertebral fracture risk and increases spine BMD in randomized trials [

52], and human studies suggest it enhances fusion and lowers pedicle screw loosening rates [

52,

53]. Several studies indicate it may be superior to bisphosphonates preoperatively [

53,

54,

55], aligning with clinical practice. In a survey of 18 multidisciplinary physicians, most recommended anabolic agents such as teriparatide or abaloparatide as first-line therapy prior to elective spine reconstruction [

45]. While abaloparatide improves BMD, bone architecture, and fracture protection, it has not yet been studied in spine surgery outcomes [

49].

Romosozumab acts as both an anabolic and antiresorptive agent by binding to and inhibiting sclerostin, a negative regulator of osteoblast activity [

56]. It has shown significant reductions in vertebral fracture risk and gains in bone mass and strength at the lumbar spine, though its effectiveness specific to spine surgery requires further study [

57,

58,

59]. Emerging evidence suggests administration two months before surgery can enhance BMD and bone strength, improving surgical outcomes and reducing complications in corrective spinal fusion surgery [

60]. In our BHC, romosozumab was the most frequently used medication among perioperative patients (33%), which may reflect both clinical efficacy and patient preference. Notably, several studies found suboptimal adherence to teriparatide [

61,

62,

63]. Adherence may be higher with monthly romosozumab injections compared with daily teriparatide.

We also examined factors influencing treatment choice. Contraindications were the primary determinant of the agent prescribed, while route of administration, dosing interval, and travel distance substantially influenced patient preference. Insurance coverage and co-payment frequently dictated final selection. Most insurance-related adjustments required opting for alternative agents in place of teriparatide or abaloparatide because of high co-payments or insurance denials despite appeals. Denosumab was commonly prescribed and had low denial rates, which likely contributed to it being the second most frequently used medication despite its antiresorptive mechanism. An anabolic-to-antiresorptive sequence was completed by 48 (27.6%) patients, consistent with literature showing that initiating therapy with an anabolic agent followed by an antiresorptive yields greater gains in bone mass, whereas starting with a bisphosphonate may blunt subsequent anabolic efficacy [

64,

65]. It should also be noted that failure to maintain bone health by following anabolic treatment with an antiresorptive medication results in rapid loss of the gains achieved in bone quality [

64,

66].

With mean post-surgical follow-up approaching two years, our overall hardware failure rate was 11.5%, with failure types including screw loosening, pullout, and rod breaking. The most common failure was screw loosening (6.9%). Notably, we observed rod breakage in 4 cases (2.3%). While the exact mechanism of failure for the rods was not uniformly documented, rod breakage in spinal fusion constructs is widely recognized in the literature as a strong surrogate indicator of pseudoarthrosis (non-union). This failure occurs due to sustained, cyclical fatigue loading on the implant caused by a failed bony fusion. These 4 cases likely represent patients with underlying non-union, a complication exacerbated in patients with poor bone quality [

40].

Only 10 patients (5.7%) required revision surgery for hardware-related complications. Prior studies report substantially higher complication burdens in osteoporotic spine populations, including overall prevalence rates near 32.1%, early complications (e.g., pedicle and compression fractures) in 13%, pseudoarthrosis with instrumentation failure in 11%, loosening of instrumentation in 7% [

8,

9]. Another study found implant loosening of up to 48.6% with revision rates of 26% in elderly patients with poor bone health [

10]. While definitions and follow-up intervals vary across studies, our observed rates appear lower than many published cohorts. The average follow-up period for our spine surgery cohort was 2.9 ± 1.7 years (705.3 ± 570.4 days), exceeding the established benchmark of 12 to 24 months commonly employed for evaluating radiographic fusion outcomes and hardware-related complications, such as screw loosening and pullout, in the spine surgery population [

67,

68,

69,

70]. This robust duration facilitates accurate assessment of both fusion success, typically defined by radiographic criteria on CT or X-ray, and the majority of early-to-mid-term device-related failures [

67,

68,

69,

70]. Notably, clinical trials and retrospective studies analyzing the impact of antifracture medications (e.g., teriparatide, romosozumab) on fusion rates and implant integrity in high-risk populations routinely employ follow-up intervals within this range, further validating our dataset’s ability to capture relevant clinical events, including an observed 11.5% hardware failure rate and the efficacy of our treatment protocols [

63,

64,

65]. Systematic screening and treatment within a dedicated BHC, frequent use of anabolic therapy with adequate preoperative lead time, multidisciplinary coordination that influences surgical planning, and postoperative follow-up may contribute to these differences. Causal effect cannot be established in this small retrospective series and must be interpreted cautiously given potential confounding by patient selection, differing surgical technique by provider, and differences in patient comorbidity profiles.

Of the 80 patients with follow-up DXA scans, 60% had improved T-scores on their most recent study, supporting the effectiveness of BHC treatment. While improved densitometry plausibly contributes to reduced hardware complications and revision surgery, prospective data are needed to confirm the relationship between perioperative bone optimization, changes in BMD, and surgical outcomes.

Limitations

This single-institution study lacks a control group, limiting causal inference and generalizability. Additionally, it is difficult to compare differences in surgical outcomes. The retrospective design introduces potential selection bias (e.g., patients willing to delay surgery and engage in optimization may differ from those who proceed without optimization). Follow-up duration was variable, and loss to follow-up may underestimate late complications or overestimate treatment success. Longer term follow-up (5+ years) is needed to assess for long-term hardware failure. In addition, we acknowledge that using either x-ray or CT scan to detect hardware failure may lead to under-detection of some types of hardware failure, such as subtle screw loosening. However, given the significant amount of increased radiation with CT scans, this is not standard of care for patients who are doing well postoperatively at our institution. CT scans were therefore only obtained for patients in whom hardware failure was suspected due to x-rays or clinical concerns. Another limitation is that due to the relatively low hardware failure rate and our sample size, we are not adequately powered to detect differences between specific medication prescriptions across patients with different BMD classifications. However, our results do suggest that our anabolic-first strategy has promising results for high-risk patients. Finally, therapy management were influenced by insurance coverage and co-payments, which vary across regions and health systems. Surgical techniques were not standardized and may confound outcome comparisons.