Optimizing Interdisciplinary Referral Pathways for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Management Across Cardiology and Pulmonology Specialties in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Burden of COPD

1.2. Epidemiology and Economic Burden in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA)

1.3. Risk Factors for COPD

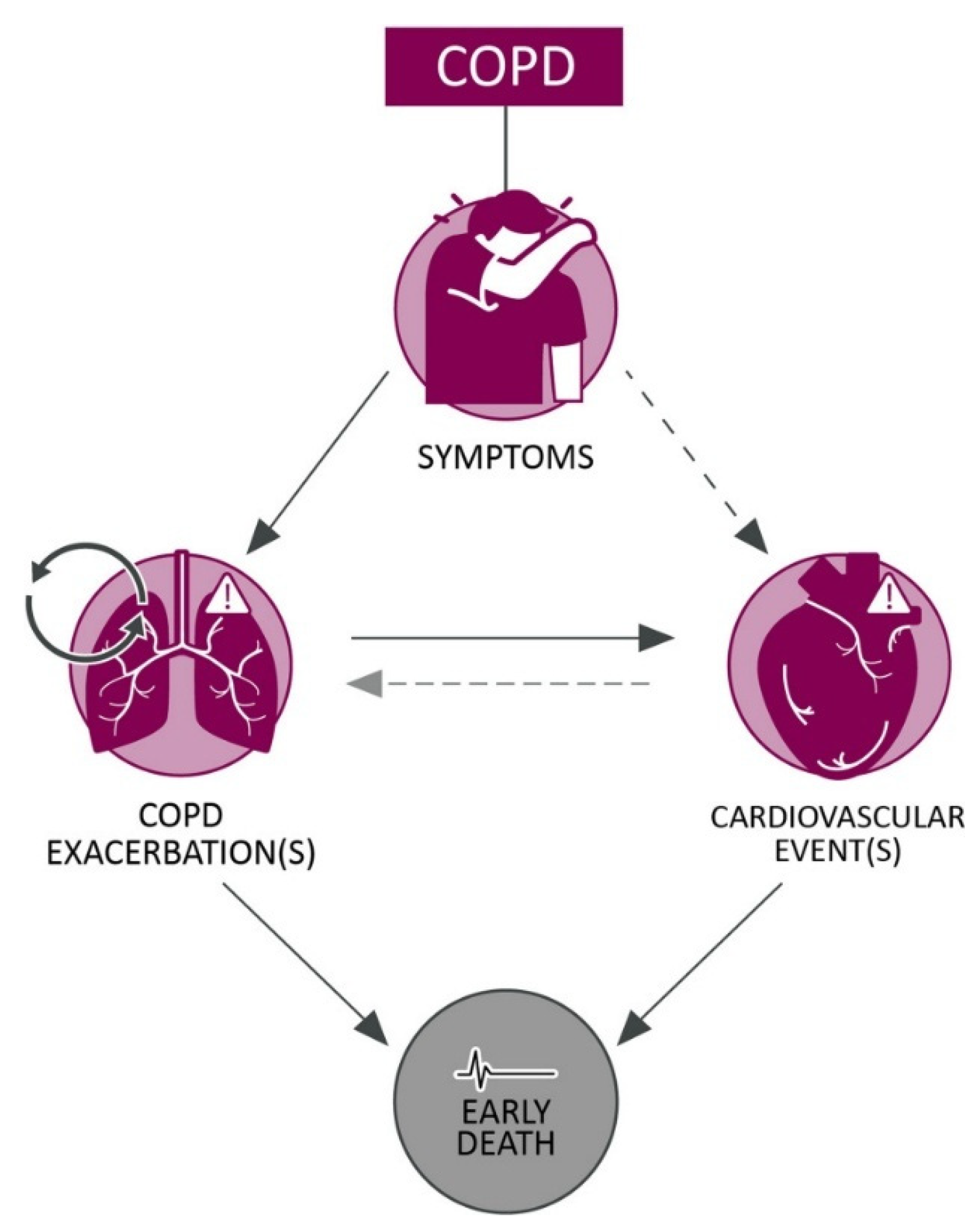

1.4. COPD and Cardiovascular Comorbidities

1.5. COPD Exacerbations and CVD Outcomes

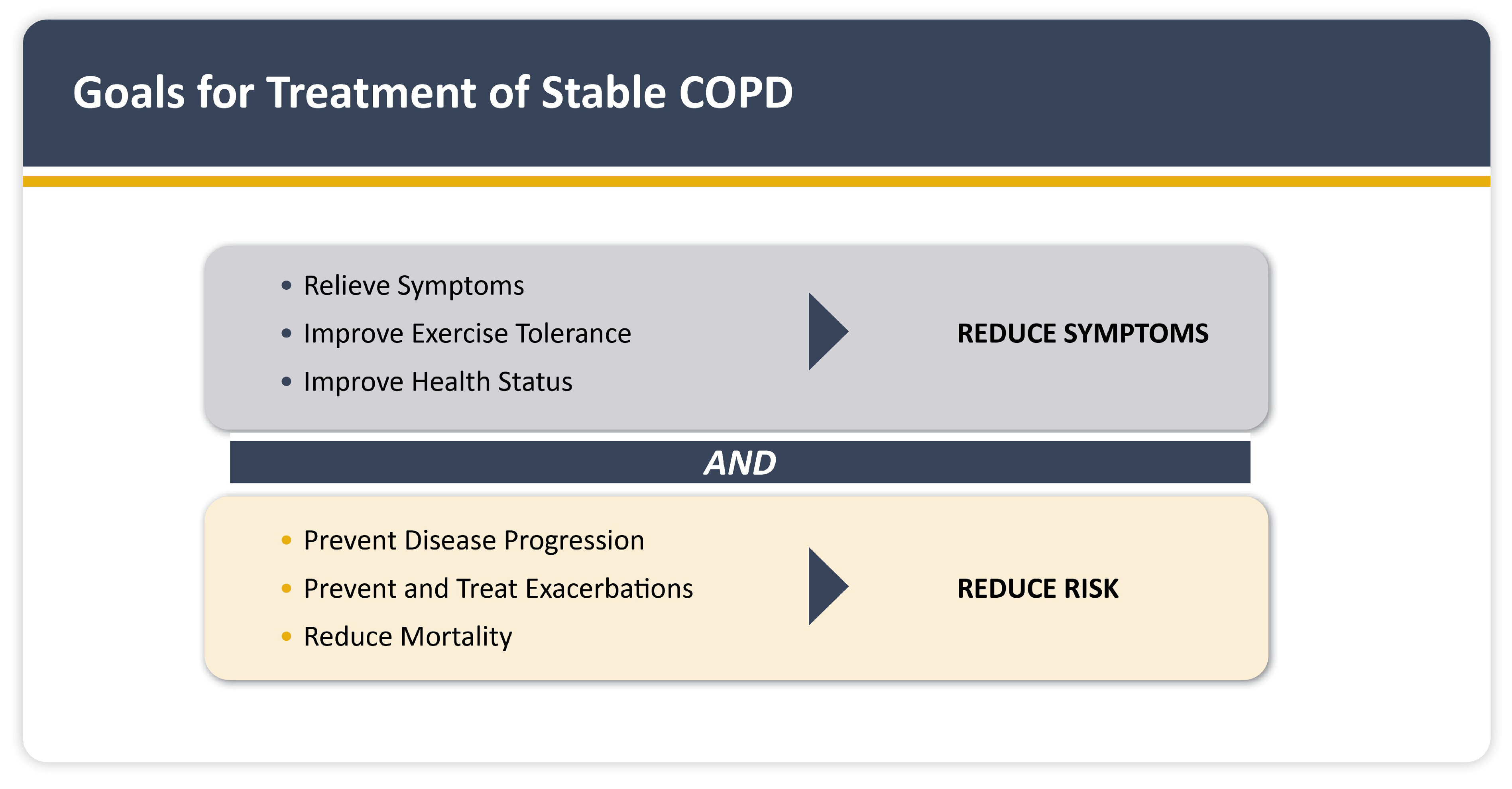

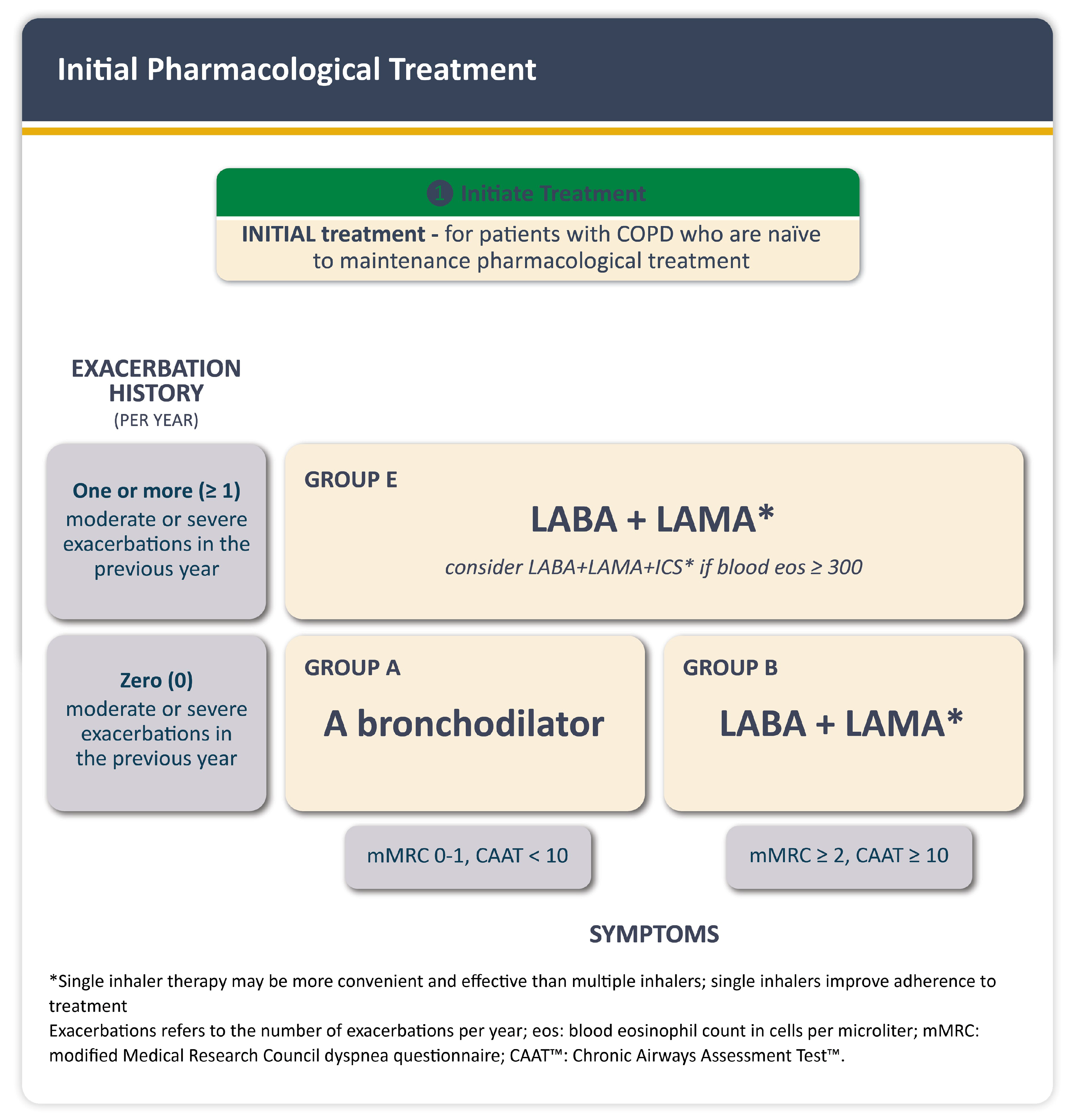

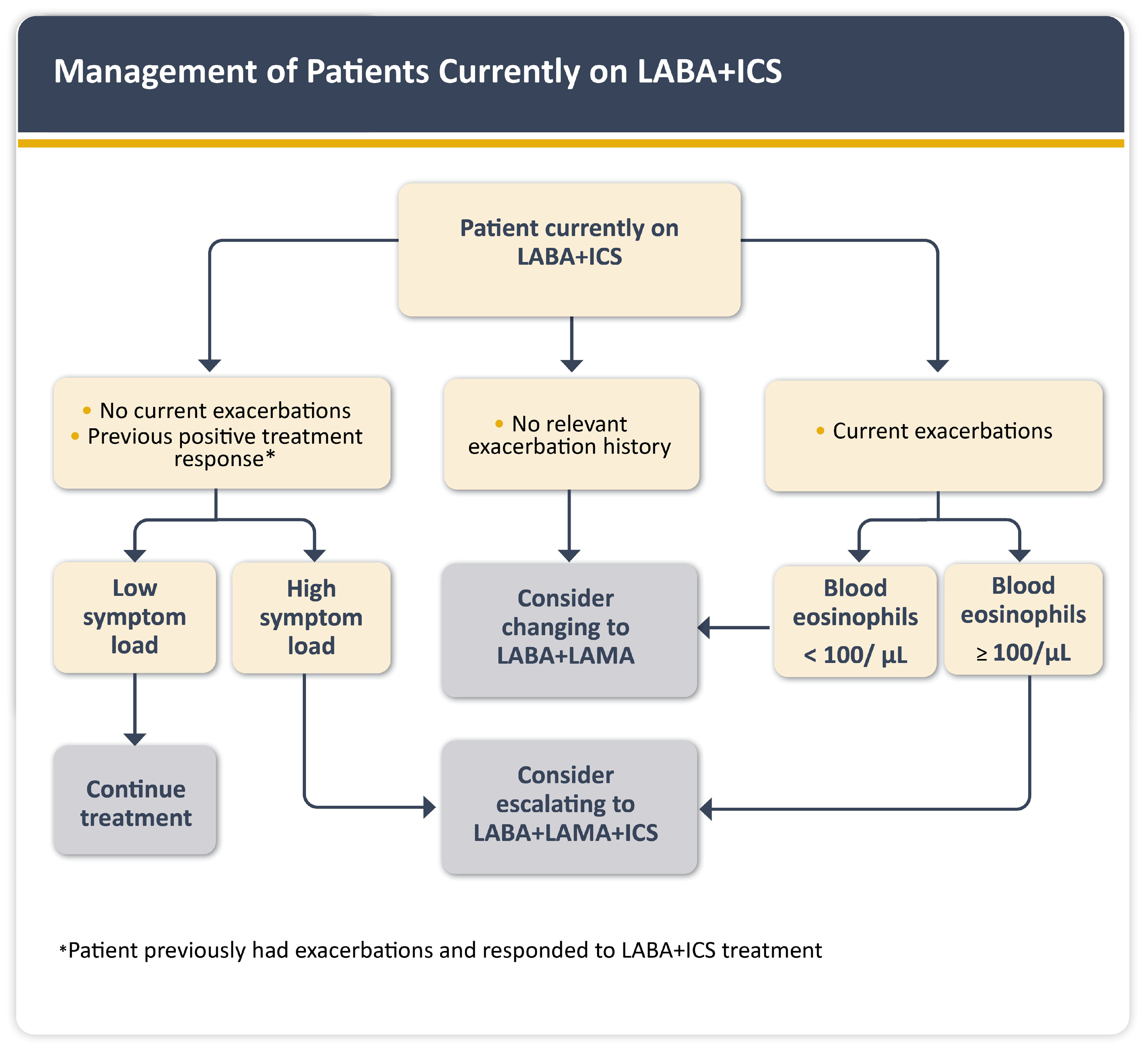

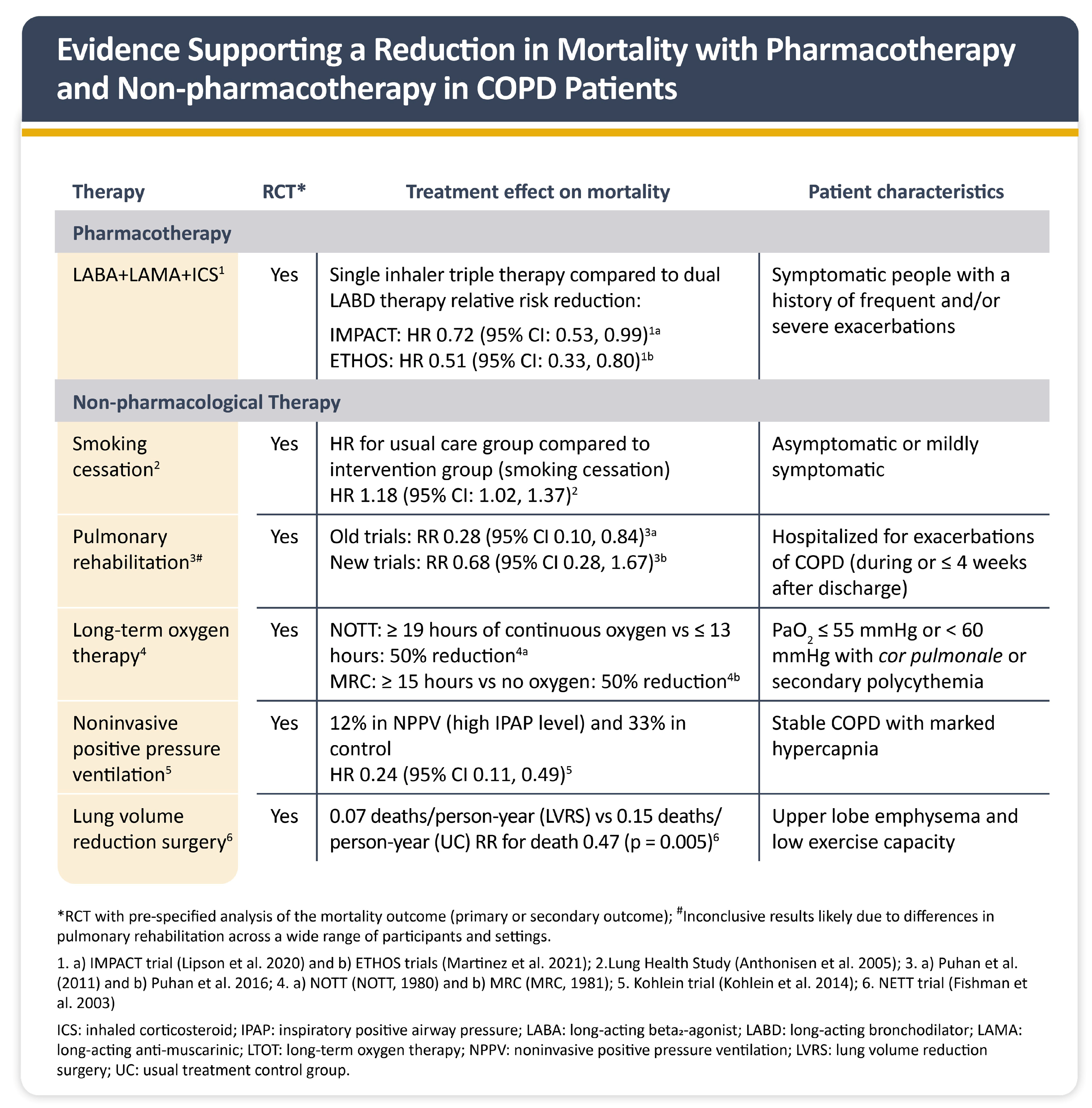

1.6. Management of COPD and CVD Comorbidities

1.7. Diagnostic Challenges, Care Gaps, and Rationale for Bi-Directional Referral Pathways

2. Materials and Methods

- Cardiology-to-Pulmonology referral algorithm to guide cardiologists/non-pulmonologists in identifying patients with suspected or undiagnosed COPD.

- Pulmonology-to-Cardiology referral algorithm to guide pulmonologists in evaluating cardiovascular risk and referring patients for cardiac evaluation.

3. Results

3.1. Cardiology-to-Pulmonology Referral Algorithm

3.2. Pulmonology-to-Cardiology Referral Algorithm

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| GOLD | Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease |

| STS | Society of Thoracic Surgeons |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| PH | Pulmonary Hypertension |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| DALY | Disability-Adjusted Life Year |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa |

| PRISm | Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry |

| KSA | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| NCD | Noncommunicable Disease |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| PEN | Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions |

| ACS | Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| AECOPD | Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| LAMA | Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonist |

| LABA | Long-Acting Beta-2 Agonist |

| ICS | Inhaled Corticosteroid |

| TFDC | Triple Fixed-Dose Combination (LAMA+LABA+ICS) |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| SMARC | Saudi Medical Appointments and Referrals Centre |

| GDMT | Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy |

| PUMA | Prevalence, Underdiagnosis, and Management of COPD in Latin America (questionnaire) |

| TAPSE | Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion |

| HFmrEF | Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction |

| HFpEF | Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction |

| 6MWD | 6-Minute Walk Distance |

| MACEs | Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events |

| RV | Right Ventricle |

| LV | Left Ventricle |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

References

- 2024, 2025 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease–GOLD: Deer Park, IL, USA, 2025; Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Wang, Z.; Lin, J.; Liang, L.; Huang, F.; Yao, X.; Peng, K.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, J. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2021: An analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Respir Res 2025, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tageldin, M.A.; Nafti, S.; Khan, J.A.; Nejjari, C.; Beji, M.; Mahboub, B.; Obeidat, N.M.; Uzaslan, E.; Sayiner, A.; Wali, S.; et al. Distribution of COPD-related symptoms in the Middle East and North Africa: Results of the BREATHE Study. Respir. Med. 2012, 106, S25–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jahdali, H.; Al-Lehebi, R.; Lababidi, H.; Alhejaili, F.F.; Habis, Y.; Alsowayan, W.A.; Idrees, M.M.; Zeitouni, M.O.; Alshimemeri, A.; Al Ghobain, M.; et al. The Saudi Thoracic Society evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2025, 20, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. All-cause readmission rate and risk factors of 30- and 90-day after discharge in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Kuhn, M.; Prettner, K.; Yu, F.; Yang, T.; Bärnighausen, T.; Bloom, D.E.; Wang, C. The Global Economic Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease for 204 Countries and Territories in 2020–2050: A Health-Augmented Macroeconomic Modelling Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1183–e1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd) (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Feizi, H.; Alizadeh, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Noori, M.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Ahmadian Heris, J.; Kolahi, A.-A.; Collins, G.S.; Safiri, S. The burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in the Middle East and North Africa region, 1990–2019. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, J.S. Prevalence, incidence, morbidity, and mortality rates of COPD in Saudi Arabia: Trends in burden of COPD from 1990 to 2019. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Malkin, J.D.; Baid, D.; Alqunaibet, A.; Mahdi, K.; Al-Thani, M.B.H.; Abdulla Bin Belaila, B.; Al Nawakhtha, E.; Alqahtani, S.; El-Saharty, S.; et al. The impact of seven major noncommunicable diseases on direct medical costs, absenteeism, and presenteeism in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. J. Med. Econ. 2021, 24, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkin, J.; Finkelstein, E.; Baid, D.; Alqunaibet, A.; Almudarra, S.; Herbst, C.H.; Dong, D.; Alsukait, R.; El-Saharty, S.; Algwizani, A. Impact of noncommunicable diseases on direct medical costs and worker productivity, Saudi Arabia. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2022, 28, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettiger, D.C.; Lin, T.K.; Almansour, M.; Hamza, M.M.; Alsukait, R.; Herbst, C.H.; Altheyab, N.; Afghani, A.; Kattan, F. Projected impact of population aging on non-communicable disease burden and costs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2020–2030. BMC Health Serv Res 2023, 23, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federation of International Pharmacists (FIP). The state of COPD in Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://ncd.fip.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/The-state-of-COPD-in-Saudi-Arabia.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. The Investment Case for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention and Control in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [Internet]; WHO and UNDP: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://files.acquia.undp.org/public/migration/sa/180326-MOH-KSA-NCDs-2017.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Adeloye, D.; Song, P.; Zhu, Y.; Campbell, H.; Sheikh, A.; Rudan, I. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Smoking Is the Leading Cause of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/15-11-2023-smoking-is-the-leading-cause-of-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Homoud, M.M.; Qoutah, R.; Krishna, G.; Harbli, N.; Saaty, L.; Obaidan, A.; Alkhathami, A.; Jamil, N.; Alkayyat, T.M.; Alsughayyir, M.; et al. Comparative Assessment of Respiratory, Hematological and Inflammatory Profiles of Long-Term Users of Cigarettes, Shisha, and e-Cigarettes in Saudi Arabia. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2025, 23, 8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaqbani, S.M. Investigating the Association between Vape Use and Respiratory Symptoms in Adults in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2023, 93, 7887–7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaiei, M.; Cafarella, P.; Frith, P.; McEvoy, R.D.; Effing, T. Factors Influencing Management of Chronic Respiratory Diseases in General and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Particular in Saudi Arabia: An Overview. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2018, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, J.S.; Aldhahir, A.M.; Siraj, R.A.; Alqarni, A.A.; AlDraiwiesh, I.A.; AlAnazi, A.F.; Alamri, A.H.; Bajahlan, R.S.; Hakami, A.A.; Alghamdi, S.M.; et al. A Nationwide Survey of Public COPD Knowledge and Awareness in Saudi Arabia: A Population-Based Survey of 15,000 Adults. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogliani, P.; Ritondo, B.L.; Laitano, R.; Chetta, A.; Calzetta, L. Advances in Understanding of Mechanisms Related to Increased Cardiovascular Risk in COPD. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2021, 15, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklós, Z.; Horváth, I. The Role of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Cardiovascular Comorbidities in COPD. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulea, C.; Zakeri, R.; Quint, J.K. Differences in Outcomes between Heart Failure Phenotypes in Patients with Coexistent Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Cohort Study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2022, 19, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiss, H.; Mayer, L.; Furian, M.; Schneider, S.R.; Müller, J.; Saxer, S.; Mademilov, M.; Titz, A.; Shehab, A.; Reimann, L.; et al. Right Ventricular Strain Impairment Due to Hypoxia in Patients with COPD: A Post Hoc Analysis of Two Randomized Controlled Trials. Open Heart 2025, 12, e002837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Han, M.K.; Hawkins, N.M.; Hurst, J.R.; Kocks, J.W.H.; Skolnik, N.; Stolz, D.; El Khoury, J.; Gale, C.P. Implications of Cardiopulmonary Risk for the Management of COPD: A Narrative Review. Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 2151–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sá-Sousa, A.; Rodrigues, C.; Jácome, C.; Cardoso, J.; Fortuna, I.; Guimarães, M.; Pinto, P.; Sarmento, P.M.; Baptista, R. Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, H.A.R.; Zubaid, M.; Mahmeed, W.A.l.; El-Menyar, A.A.; Ridha, M.; Alsheikh-Ali, A.A.; Singh, R.; Assad, N.; Al Habib, K.; Al Suwaidi, J. Prevalence and Prognosis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among 8167 Middle Eastern Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome. Clin. Cardiol. 2010, 33, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelmeier, C.F.; Rhodes, K.; Garbe, E.; Abram, M.; Halbach, M.; Müllerová, H.; Kossack, N.; Timpel, P.; Kolb, N.; Nordon, C. Elucidating the Risk of Cardiopulmonary Consequences of an Exacerbation of COPD: Results of the EXACOS-CV Study in Germany. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2024, 11, e002153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Manito, N.; Sánchez-Covisa, J.; Hernández, I.; Corregidor, C.; Escudero, L.; Rhodes, K.; Nordon, C. Risk of Severe Cardiovascular Events Following COPD Exacerbations: Results from the EXACOS-CV Study in Spain. Rev. Española De Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2025, 78, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnant, S.R.A.; De Roos, E.; Kavousi, M.; Stricker, B.H.; Terzikhan, N.; Lahousse, L.; Brusselle, G.G. Trajectory and Mortality of Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry: The Rotterdam Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1901217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapsomaniki, E.; Hughes, R.; Make, B.; Del Olmo, R.; Papi, A.; Price, D.; Belton, L.; Franzen, S.; Vestbo, J.; Müllerová, H.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes in Patients with Pre-COPD or PRISm in NOVELTY. In Monitoring Airway Disease; European Respiratory Society: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2023; p. OA4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, D.; Mkorombindo, T.; Schumann, D.M.; Agusti, A.; Ash, S.Y.; Bafadhel, M.; Bai, C.; Chalmers, J.D.; Criner, G.J.; Dharmage, S.C.; et al. Towards the Elimination of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Lancet Commission. Lancet 2022, 400, 921–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentaro, G.; Pelaia, C.; Cassano, V.; Miceli, S.; Maio, R.; Perticone, M.; Pastori, D.; Pignatelli, P.; Andreozzi, F.; Violi, F.; et al. Association between right ventricular dysfunction and adverse cardiac events in mild COPD patients. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 53, e13887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, J.H.; Lu, H.; Kondo, T.; Bachus, E.; de Boer, R.A.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Jhund, P.S.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.A.; et al. Heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: Insights from DELIVER. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 2078–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monshi, S.S.; Alanazi, A.M.M.; Alzahrani, A.M.; Alzhrani, A.A.; Arbaein, T.J.; Alharbi, K.K.; ZAlqahtani, M.; Alzahrani, A.H.; AElkhobby, A.; Almazrou, A.M.; et al. Awareness and Utilization of Smoking Cessation Clinics in Saudi Arabia, Findings from the 2019 Global Adult Tobacco Survey. Subst. Abus. Treat Prev. Policy 2023, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2025, 2026 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease–GOLD: Deer Park, IL, USA, 2025; Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2026-gold-report-and-pocket-guide/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e895–e1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, D.A.; Crim, C.; Criner, G.J.; Day, N.C.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Han, M.K.; Jones, C.E.; Kilbride, S.; Lange, P.; et al. Reduction in All-Cause Mortality with Fluticasone Furoate/Umeclidinium/Vilanterol in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.J.; Rabe, K.F.; Ferguson, G.T.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Singh, D.; Wang, C.; Rossman, K.; St Rose, E.; Trivedi, R.; Ballal, S.; et al. Reduced All-Cause Mortality in the ETHOS Trial of Budesonide/Glycopyrrolate/Formoterol for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter, Parallel-Group Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonisen, N.R.; Skeans, M.A.; Wise, R.A.; Manfreda, J.; Kanner, R.E.; Connett, J.E.; Lung Health Study Research Group. The Effects of a Smoking Cessation Intervention on 14.5-Year Mortality: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhan, M.A.; Gimeno-Santos, E.; Scharplatz, M.; Troosters, T.; Walters, E.H.; Steurer, J. Pulmonary Rehabilitation Following Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 10, CD005305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhan, M.A.; Gimeno-Santos, E.; Cates, C.J.; Troosters, T. Pulmonary Rehabilitation Following Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 12, CD005305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial (NOTT) Group. Continuous or Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy in Hypoxemic Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: A Clinical Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1980, 93, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical Research Council (MRC) Working Party. Long-Term Domiciliary Oxygen Therapy in Chronic Hypoxic Cor Pulmonale Complicating Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema. Lancet 1981, 1, 681–686. [Google Scholar]

- Köhnlein, T.; Windisch, W.; Köhler, D.; Drabik, A.; Geiseler, J.; Hartl, S.; Karg, O.; Laier-Groeneveld, G.; Nava, S.; Schönhofer, B.; et al. Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation for the Treatment of Severe Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Prospective, Multicentre, Randomised, Controlled Clinical Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, A.; Martinez, F.; Naunheim, K.; Piantadosi, S.; Wise, R.; Ries, A.; Weinmann, G.; Wood, D.E. National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. A Randomized Trial Comparing Lung-Volume-Reduction Surgery with Medical Therapy for Severe Emphysema. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2059–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaphe, M.A.; Alshehri, M.; Alajam, R.A.; Ghazwani, A.; Temehy, B.F.; Sahely, A.; Alfaifi, B.H.; Hakamy, A.; Khan, A.; Aafreen, A.; et al. Evaluating the physiological responses to treadmill exercise based on the 6-minute walk test in individuals with COPD across severity levels. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1668559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammri, G.F.; Almutairi, B.N.; Almutairi, M.A. Proposed protocol for developing a rehabilitation program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Phys. Ther. Res. Pract. 2024, 3, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, F.H. Optimizing Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Saudi Arabia: Current Practices, Challenges, and Future Directions. Medicina 2025, 61, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.T.; Glasziou, P.; Dobler, C.C. Use of the Terms “Overdiagnosis” and “Misdiagnosis” in the COPD Literature: A Rapid Review. Breathe 2019, 15, e8–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, M.; Franssen, F.M.E.; Olschewski, H.; Lainscak, M.; Böhm, M.; Tavazzi, L.; Rosenkranz, S. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Gaps in Patients With Heart Failure and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tash, A.A.; Al-Bawardy, R.F. Cardiovascular Disease in Saudi Arabia: Facts and the Way Forward. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2023, 35, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljerian, N.A.; Alharbi, A.A.; AlOmar, R.S.; Binhotan, M.S.; Alghamdi, H.A.; Arafat, M.S.; Aldhabib, A.; Alabdulaali, M.K. Showcasing the Saudi E-Referral System Experience: The Epidemiology and Pattern of Referrals Utilising Nationwide Secondary Data. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1348442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehab, A.; Alzaabi, A.; Al Zubaidi, A.; Mahboub, B.; Skouri, H.; Alhameli, H.; El-Tamimi, H.; Iqbal, M.N. Streamlining Referrals by Establishing a UAE-Specific Referral Algorithm for CVD Patients with Overlapping COPD: A Collaborative Effort by Cardiologists and Pulmonologists. Front Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1531966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrikrishna, D.; Steer, J.; Bostock, B.; Dickinson, S.W.; Piwko, A.; Ramalingam, S.; Saggu, R.; Stonham, C.A.; Storey, R.F.; Taylor, C.J.; et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and the Management of Cardiopulmonary Risk in the UK: A Systematic Literature Review and Modified Delphi Study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2025, 20, 2073–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C.P.; Hurst, J.R.; Hawkins, N.M.; Bourbeau, J.; Han, M.K.; Lam, C.S.P.; Marciniuk, D.D.; Price, D.; Stolz, D.; Gluckman, T.; et al. Identification and Management of Cardiopulmonary Risk in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, zwaf119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Chiara, C.; Sartori, G.; Fantin, A.; Castaldo, N.; Crisafulli, E. Reducing Hospital Readmissions in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients: Current Treatments and Preventive Strategies. Med. (B Aires) 2025, 61, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lai, W.; Lin, C.; Qiu, K.; Wu, J.; Yao, W. Triple Therapy in the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2018, 363, k4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miguel-Díez, J.; Núñez Villota, J.; Santos Pérez, S.; Manito Lorite, N.; Alcázar Navarrete, B.; Delgado Jiménez, J.F.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Pascual Figal, D.; Sobradillo Ecenarro, P.; Gómez Doblas, J.J. Multidisciplinary Management of Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Cardiovascular Disease. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2024, 60, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, C.J.; Steigner, M.L.; Piazza, G.; Goldhaber, S.Z. Collaborative Cardiology and Pulmonary Management of Pulmonary Hypertension. Chest 2019, 156, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au-Doung, P.L.W.; Wong, C.K.M.; Chan, D.C.C.; Chung, J.W.H.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Leung, M.K.W. PUMA Screening Tool to Detect COPD in High-Risk Patients in Chinese Primary Care–A Validation Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.-C.; Hsiao, Y.-H.; Ko, H.-K.; Chou, K.-T.; Jeng, T.-H.; Perng, D.-W. The Accuracy of PUMA Questionnaire in Combination With Peak Expiratory Flow Rate to Identify At-Risk, Undiagnosed COPD Patients. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2024, 60, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344249 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Solomon, J.; Dauber-Decker, K.; Richardson, S.; Levy, S.; Khan, S.; Coleman, B.; Persaud, R.; Chelico, J.; King, D.; Spyropoulos, A.; et al. Integrating Clinical Decision Support Into Electronic Health Record Systems Using a Novel Platform (EvidencePoint): Developmental Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e44065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Idrees, M.M.; Habis, Y.Z.; Jelaidan, I.; Alsowayan, W.; Almogbel, O.; Alasiri, A.M.; Al-Ghamdi, F.; Bakhsh, A.; Alhejaili, F. Optimizing Interdisciplinary Referral Pathways for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Management Across Cardiology and Pulmonology Specialties in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8865. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248865

Idrees MM, Habis YZ, Jelaidan I, Alsowayan W, Almogbel O, Alasiri AM, Al-Ghamdi F, Bakhsh A, Alhejaili F. Optimizing Interdisciplinary Referral Pathways for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Management Across Cardiology and Pulmonology Specialties in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8865. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248865

Chicago/Turabian StyleIdrees, Majdy M., Yahya Z. Habis, Ibrahim Jelaidan, Waleed Alsowayan, Osama Almogbel, Abdalla M. Alasiri, Faisal Al-Ghamdi, Abeer Bakhsh, and Faris Alhejaili. 2025. "Optimizing Interdisciplinary Referral Pathways for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Management Across Cardiology and Pulmonology Specialties in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8865. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248865

APA StyleIdrees, M. M., Habis, Y. Z., Jelaidan, I., Alsowayan, W., Almogbel, O., Alasiri, A. M., Al-Ghamdi, F., Bakhsh, A., & Alhejaili, F. (2025). Optimizing Interdisciplinary Referral Pathways for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Management Across Cardiology and Pulmonology Specialties in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8865. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248865