Should the Approach to Pre-Procedural Cardiological Diagnostics in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease Be Reconsidered? The Prevalence of Coronary Artery Disease in Asymptomatic Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CABG | Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CCTA | Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CS | Carotid Artery Disease/Carotid Stenosis |

| DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| FFR | Fractional Flow Reserve |

| HA | Arterial Hypertension |

| IVUS | Intravascular Ultrasound |

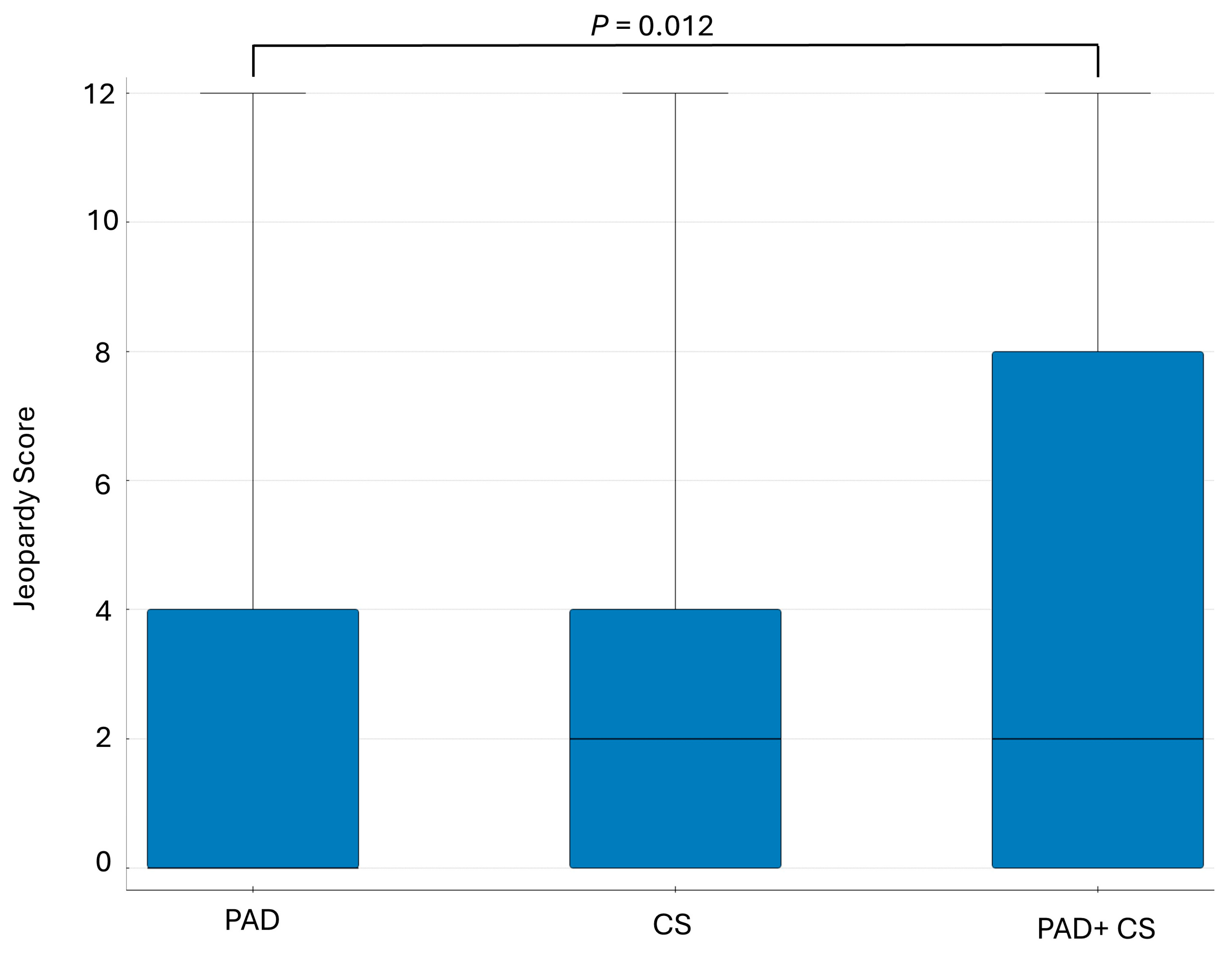

| JSC | Jeopardy Score |

| LM | Left Main Coronary Artery |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PAD | Peripheral Artery Disease |

| PCI | Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| PL | Polska/Poland |

| PTA | Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty |

| PTCA | Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TIA | Transient Ischemic Attack |

| USA | United States of America |

References

- Welten, G.M.J.M.; Schouten, O.; Hoeks, S.E.; Chonchol, M.; Vidakovic, R.; van Domburg, R.T.; Bax, J.J.; van Sambeek, M.R.; Poldermans, D. Long-Term Prognosis of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 1588–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalke, J.B.; Hiremath, S.; Makhale, C.N. A cross-sectional study on coronary artery disease diagnosis in patients with peripheral artery disease. J. Interv. Med. 2022, 5, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzolai, L.; Teixido-Tura, G.; Lanzi, S.; Boc, V.; Bossone, E.; Brodmann, M.; Bura-Rivière, A.; De Backer, J.; Deglise, S.; Della Corte, A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3538–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuuti, J.; Wijns, W.; Saraste, A.; Capodanno, D.; Barbato, E.; Funck-Brentano, C.; Prescott, E.; Storey, R.F.; Deaton, C.; Cuisset, T.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 407–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Califf, R.M.; Phillips, H.R.; Hindman, M.C.; Mark, D.B.; Lee, K.L.; Behar, V.S.; Johnson, R.A.; Pryor, D.B.; Rosati, R.A.; Wagner, G.S.; et al. Prognostic value of a coronary artery jeopardy score. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1985, 5, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezad, S.M.; McEntegart, M.; Dodd, M.; Didagelos, M.; Sidik, N.; Li Wa, M.K.; Morgan, H.P.; Pavlidis, A.; Weerackody, R.; Walsh, S.J.; et al. Impact of Anatomical and Viability-Guided Completeness of Revascularization on Clinical Outcomes in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 84, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnelli, G.; Belch, J.J.F.; Baumgartner, I.; Giovas, P.; Hoffmann, U. Morbidity and mortality associated with atherosclerotic peripheral artery disease: A systematic review. Atherosclerosis 2020, 293, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.W.; Kim, B.G.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, B.O.; Byun, Y.S.; Rhee, K.J.; Lee, B.K.; Goh, C.W. Prediction of Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease. Int. Heart J. 2015, 56, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuruskan, E.; Saracoglu, E.; Polat, M.; Duzen, I.V. Prediction of coronary artery disease severity in lower extremity artery disease patients: A correlation study of TASC II classification, Syntax and Syntax II scores. Cardiol. J. 2017, 24, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereg, D.; Elis, A.; Neuman, Y.; Mosseri, M.; Segev, D.; Granek-Catarivas, M.; Lishner, M.; Hermoni, D. Comparison of mortality in patients with coronary or peripheral artery disease following the first vascular intervention. Coron. Artery Dis. 2014, 25, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eikelboom, J.W.; Bhatt, D.L.; Fox, K.A.A.; Bosch, J.; Connolly, S.J.; Anand, S.S.; Avezum, A.; Berkowitz, S.D.; Branch, K.R.; Dagenais, G.R.; et al. Mortality Benefit of Rivaroxaban Plus Aspirin in Patients With Chronic Coronary or Peripheral Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, K.K.W.; Gyldenkerne, C.; Thim, T.; Thomsen, R.W.; Maeng, M. Peripheral artery disease, lower limb revascularization, and amputation in diabetes patients with and without coronary artery disease: A cohort study from the Western Denmark Heart Registry. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2021, 9, e001803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertzer, N.R.; Beven, E.G.; Young, J.R.; O’hara, P.J.; Ruschhaupt, W.F.; Graor, R.A.; Dewolfe, V.G.; Maljovec, L.C. Coronary Artery Disease in Peripheral Vascular Patients: A Classification of 1000 Coronary Angiograms and Results of Surgical Management. Ann. Surg. 1984, 199, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illuminati, G.; Ricco, J.B.; Greco, C.; Mangieri, E.; Calio’, F.; Ceccanei, G.; Pacile, M.A.; Schiariti, M.; Tanzilli, G.; Barillà, F.; et al. Systematic Preoperative Coronary Angiography and Stenting Improves Postoperative Results of Carotid Endarterectomy in Patients with Asymptomatic Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2010, 39, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, R. Coronary angiography in patients undergoing carotid artery stenting shows a high incidence of significant coronary artery disease. Heart 2005, 91, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, D.J.; Kizilgul, M.; Aung, W.W.; Roussillon, K.C.; Keeley, E.C. Frequency of Coronary Artery Disease in Patients Undergoing Peripheral Artery Disease Surgery. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, K.; Morton, G.; Sicard, P.; Chong, E.; Indermuehle, A.; Clapp, B.; Thomas, M.; Redwood, S.; Perera, D. Prognostic Utility of BCIS Myocardial Jeopardy Score for Classification of Coronary Disease Burden and Completeness of Revascularization. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 111, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Kabach, M.; Patel, D.B.; Guzman, L.A.; Jovin, I.S. Radial Artery Access Complications: Prevention, Diagnosis and Management. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2022, 40, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFalls, E.O.; Ward, H.B.; Moritz, T.E.; Goldman, S.; Krupski, W.C.; Littooy, F.; Pierpont, G.; Santilli, S.; Rapp, J.; Hattler, B.; et al. Coronary-Artery Revascularization before Elective Major Vascular Surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2795–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poldermans, D.; Schouten, O.; Vidakovic, R.; Bax, J.J.; Thomson, I.R.; Hoeks, S.E.; Feringa, H.H.; Dunkelgrün, M.; de Jaegere, P.; Maat, A.; et al. A Clinical Randomized Trial to Evaluate the Safety of a Noninvasive Approach in High-Risk Patients Undergoing Major Vascular Surgery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 1763–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, M.; Stassano, P.; Di Tommaso, L.; Pepino, P.; Giordano, A.; Pinna, G.B.; Iannelli, G.; Ambrosio, G. Systematic Strategy of Prophylactic Coronary Angiography Improves Long-Term Outcome After Major Vascular Surgery in Medium- to High-Risk Patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.G.; Hong, J.Y.; Rha, S.W.; Choi, C.U.; Lee, M.S. Long-term outcomes of peripheral arterial disease patients with significant coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, J.; Migliaccio-Walle, K.; Ishak, K.J.; Proskorovsky, I. The morbidity and mortality following a diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease: Long-term follow-up of a large database. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2005, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, P.G.; Bhatt, D.L.; Wilson, P.W.F.; D’Agostino, R.; Ohman, E.M.; Röther, J.; Liau, C.S.; Hirsch, A.T.; Mas, J.L.; Ikeda, Y.; et al. One-Year Cardiovascular Event Rates in Outpatients With Atherothrombosis. JAMA 2007, 297, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Lee, C.H.; Chao, T.H.; Tseng, W.K.; Lin, T.H.; Chung, W.J.; Li, J.K.; Huang, H.L.; Liu, P.Y.; Chao, T.K.; et al. Impact of routine coronary catheterization in low extremity artery disease undergoing percutaneous transluminal angioplasty: Study protocol for a multi-center randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016, 17, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Data (n = 350) | |

| Men, n (%) | 222 (63.43%) |

| Age, years | 66 ± 8.5 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 296 (84.57%) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 146 (41.71%) |

| Type 2 diabetes on oral therapy, n (%) | 77 (22.00%) |

| Type 2 diabetes on insulin therapy, n (%) | 46 (13.14%) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 5 (1.43%) |

| Patients with a history of heart attack—at least one year before admission, n (%) | 31 (8.86%) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 202 (57.71%) |

| Past smoking, n (%) | 53 (15.14%) |

| Family history of cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 79 (22.57%) |

| Clinical Characteristics (n = 350) | |

| Isolated peripheral artery disease (PAD), n (%) | 274 (78.29%) |

| Isolated carotid artery disease, n (%) | 35 (10.00%) |

| Peripheral artery disease and carotid artery disease, n (%) | 41 (11.71%) |

| ST-T segment changes in resting ECG, n (%) | 51 (14.57%) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (%) | 60 (50–60) |

| Number of Affected Vessels | |

| Without significant coronary artery lesions, n (%) | 163 (46.57%) |

| Single-vessel disease, n (%) | 102 (29.14%) |

| Double-vessel disease, n (%) | 50 (14.28%) |

| Multivessel disease, n (%) | 35 (10.01%) |

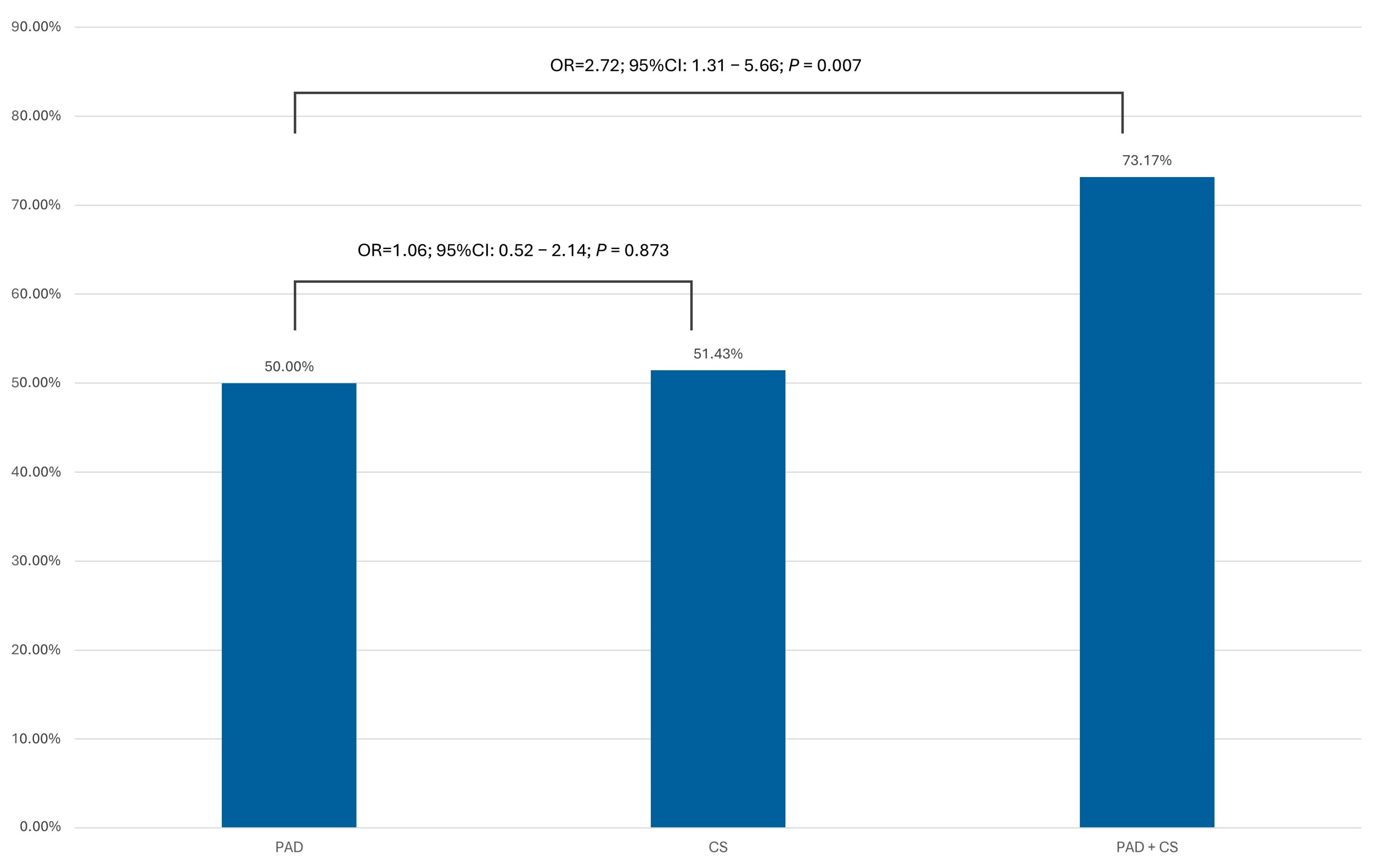

| Frequency of Significant Coronary Artery Lesions (>70% Diameter Stenosis) in the PAD, CS, and PAD + CS Subgroups | |

| Location of atherosclerosis | Present stenosis (>70% DS, >50% LM) |

| Study group, n (%) | 185 (52.86%) |

| PAD subgroup, n (%) | 137 (50.00%) |

| CS subgroup, n (%) | 18 (51.43%) |

| PAD + CS subgroup, n (%) | 30 (73.17%) |

| Presence of Significant Stenoses Depending on ECG Changes and Echocardiographic Examination | |

| Present stenosis (>70% DS, >50% LM) | |

| Patients without symptoms, without changes in ECG and echocardiographic examination- Group 1 (n = 164), n (%) | 71 (43.29%) |

| The rest of patients- Group 2 (n = 186), n (%) | 114 (61.29%) |

| (A) Univariable Logistic Regression Model | (B) Multivariable Logistic Regression Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | −95% CI | +95% CI | p-Value | OR | −95% CI | +95% CI | p-Value | |

| Age | 1.350 | 0.880 | 2.061 | 0.165 | ||||

| Sex | 1.973 | 1.269 | 3.067 | 0.003 | 1.683 | 1.053 | 2.691 | 0.029 |

| DM | 1.435 | 0.911 | 2.26 | 0.119 | ||||

| HA | 2.141 | 1.177 | 3.894 | 0.013 | 1.990 | 1.048 | 3.781 | 0.035 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.04 | 0.679 | 1.592 | 0.857 | ||||

| TIA or stroke | 2.12 | 1.172 | 3.834 | 0.013 | 1.866 | 0.997 | 3.492 | 0.051 |

| CKD | 3.624 | 0.401 | 32.758 | 0.252 | ||||

| Smoking | 0.756 | 0.47 | 1.217 | 0.250 | ||||

| Medical interview | 1.324 | 0.798 | 2.197 | 0.278 | ||||

| ECG changes | 2.72 | 1.710 | 4.325 | <0.0001 | 2.107 | 1.286 | 3.454 | 0.003 |

| Reduced LVEF | 3.875 | 1.86 | 8.073 | 0.0003 | 2.691 | 1.230 | 5.839 | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hrycek, E.; Grzadziel, G.; Konkolewska, M.; Halatek, E.; Nowakowski, P.; Buszman, P.; Milewski, K.; Zurakowski, A. Should the Approach to Pre-Procedural Cardiological Diagnostics in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease Be Reconsidered? The Prevalence of Coronary Artery Disease in Asymptomatic Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8858. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248858

Hrycek E, Grzadziel G, Konkolewska M, Halatek E, Nowakowski P, Buszman P, Milewski K, Zurakowski A. Should the Approach to Pre-Procedural Cardiological Diagnostics in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease Be Reconsidered? The Prevalence of Coronary Artery Disease in Asymptomatic Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8858. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248858

Chicago/Turabian StyleHrycek, Eugeniusz, Gabriel Grzadziel, Magda Konkolewska, Edyta Halatek, Przemyslaw Nowakowski, Piotr Buszman, Krzysztof Milewski, and Aleksander Zurakowski. 2025. "Should the Approach to Pre-Procedural Cardiological Diagnostics in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease Be Reconsidered? The Prevalence of Coronary Artery Disease in Asymptomatic Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8858. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248858

APA StyleHrycek, E., Grzadziel, G., Konkolewska, M., Halatek, E., Nowakowski, P., Buszman, P., Milewski, K., & Zurakowski, A. (2025). Should the Approach to Pre-Procedural Cardiological Diagnostics in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease Be Reconsidered? The Prevalence of Coronary Artery Disease in Asymptomatic Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8858. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248858