Comparative Outcomes of Apixaban and Acenocoumarol in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation: A Retrospective Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Age ≥ 18 years;

- CKD stages 4–5 (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, calculated using the CKD-EPI 2021 formula);

- Documented AF (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent, confirmed by ECG or Holter monitoring);

- Minimum three months of uninterrupted oral anticoagulation.

- Acute kidney injury or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis;

- Active malignancy or hematologic disease;

- Concomitant dual antiplatelet therapy;

- Recent surgery or trauma (<3 months);

- History of kidney transplantation or peritoneal dialysis;

- Hemoglobin < 7 g/dL;

- Hospitalization within 30 days for major infection;

- Missing or incomplete clinical data [6].

2.3. Data Collection and Clinical Parameters

- Major bleeding: Intracranial, retroperitoneal, or gastrointestinal bleeding requiring transfusion or hospitalization.

- Clinically relevant non-major bleeding (minor): Overt bleeding not fulfilling major criteria.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

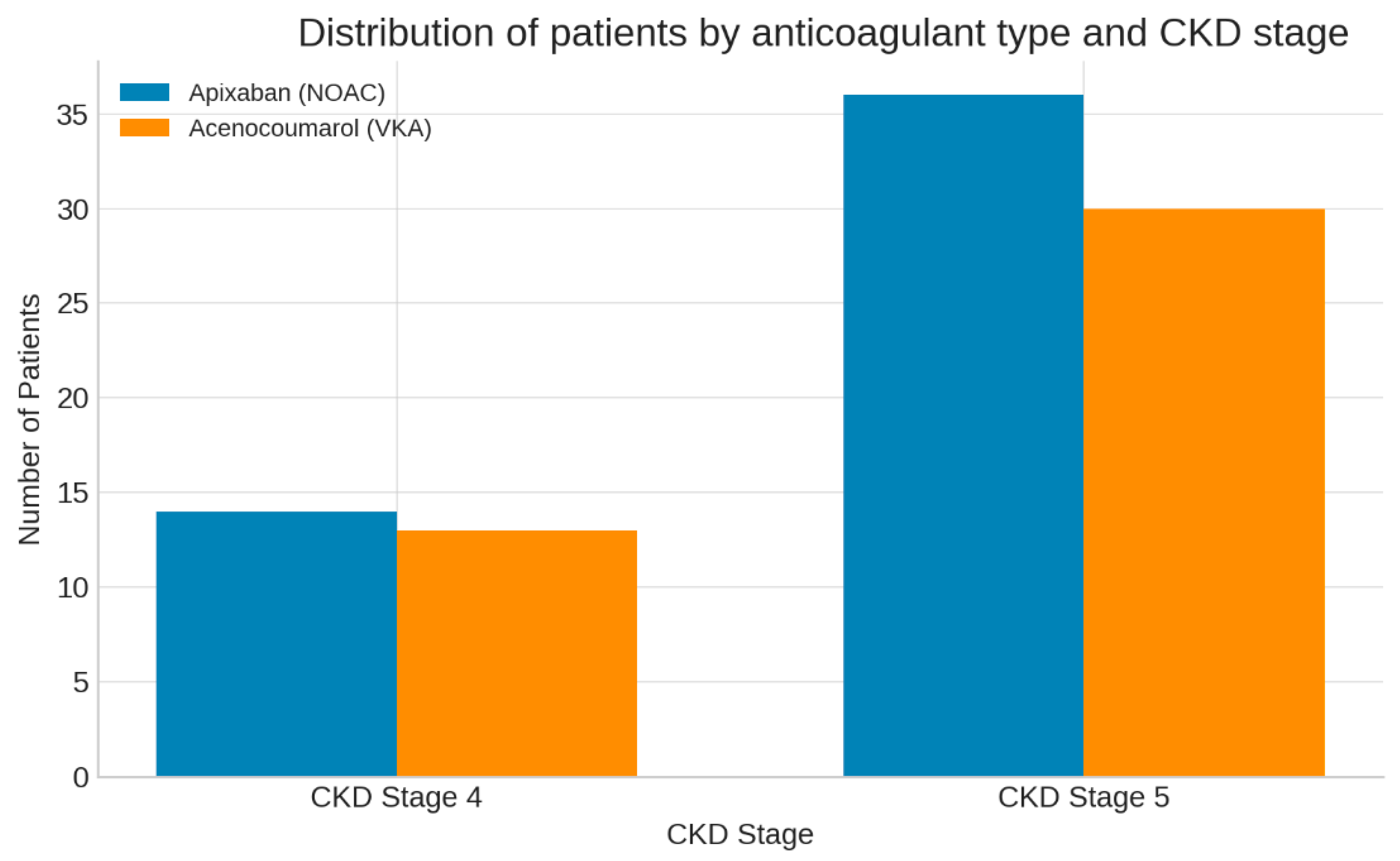

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Inflammatory and Biochemical Markers

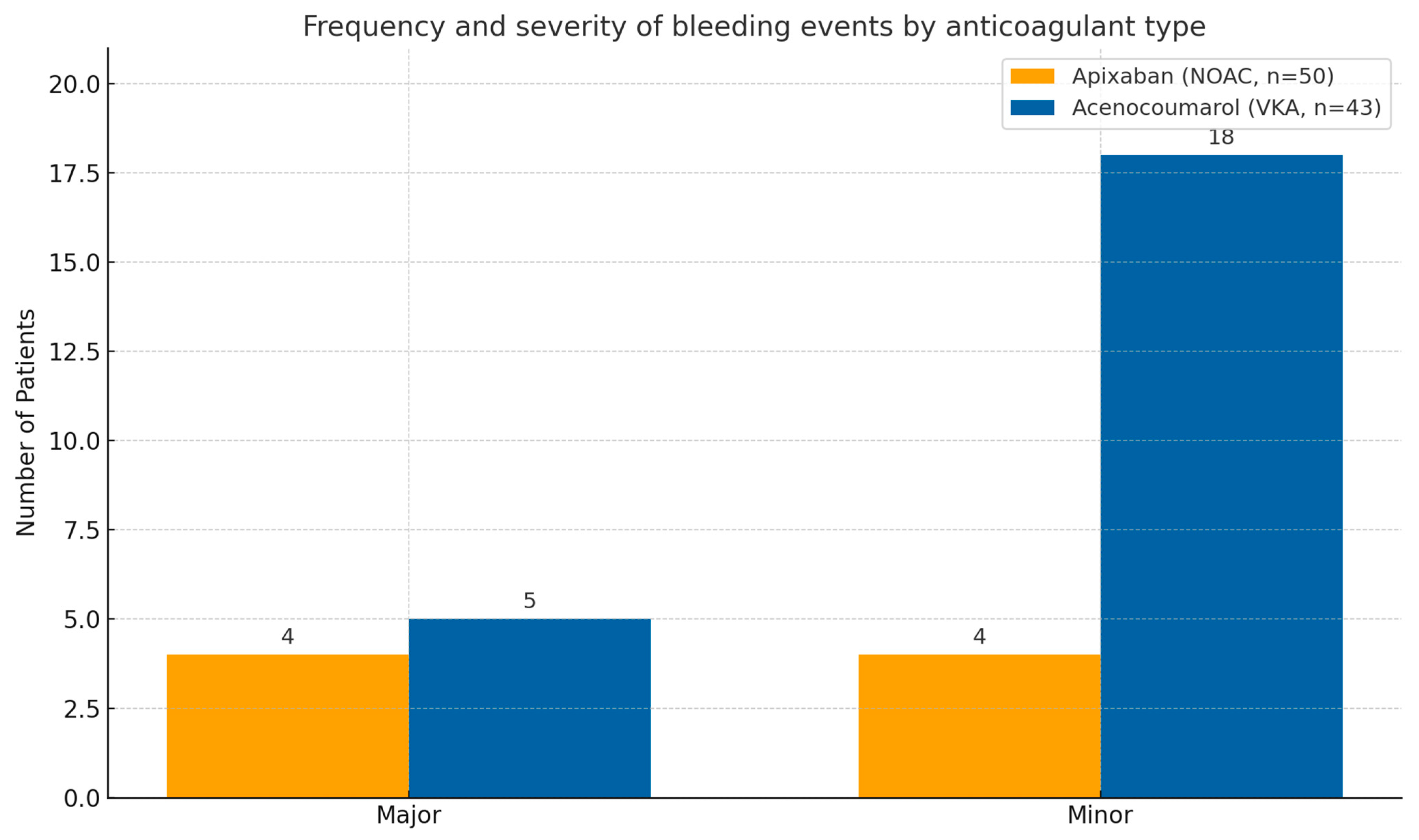

3.3. Bleeding Events

3.4. Thromboembolic Events and Mortality

3.5. Correlation Between Risk Scores and Bleeding

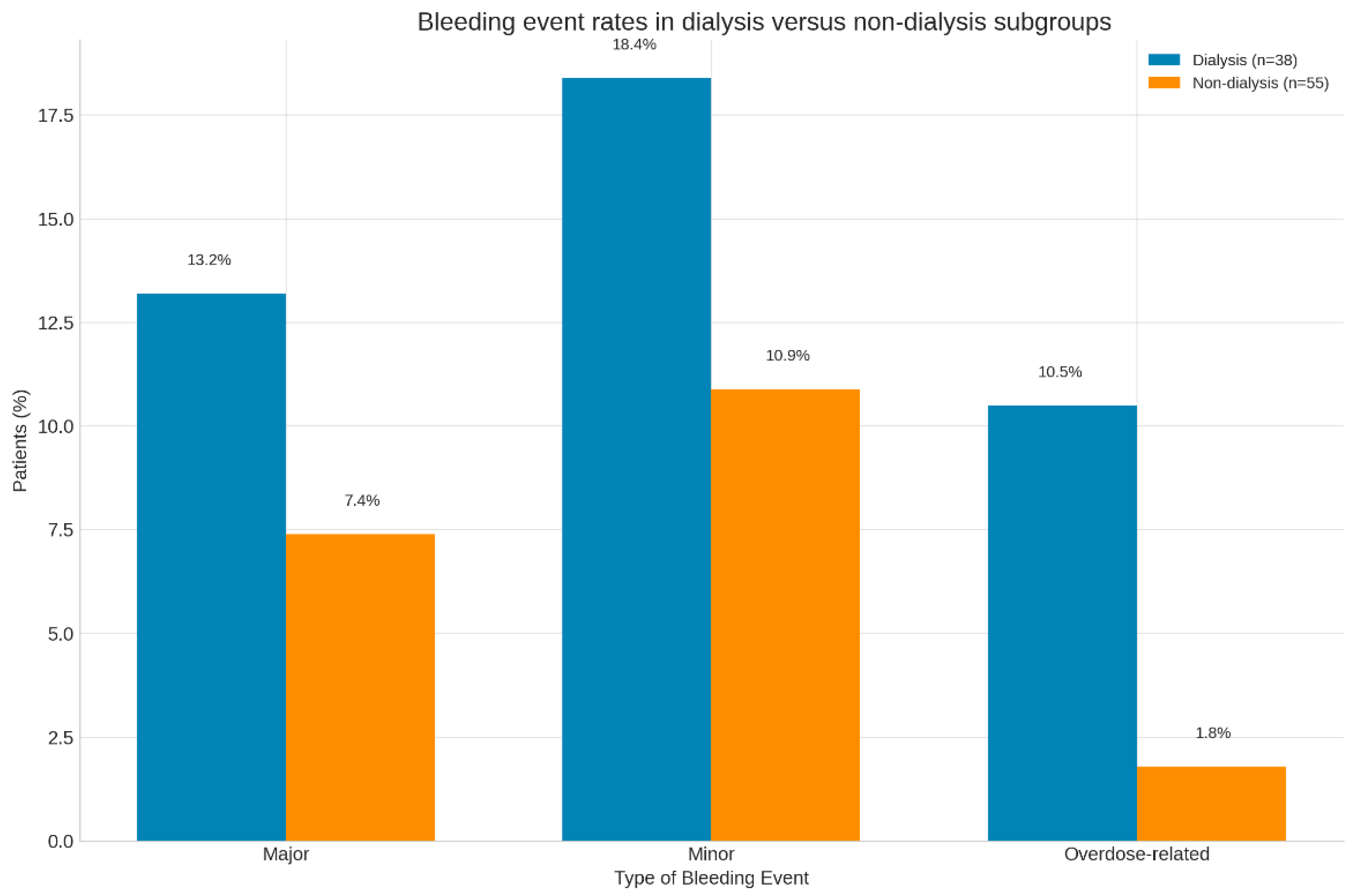

3.6. Dialysis Versus Non-Dialysis Subgroups

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Pathophysiological Insights

4.3. Dialysis Versus Non-Dialysis Patients

4.4. Clinical Relevance and Implications

4.5. Predictive Scores and Risk Stratification

4.6. Study Strengths

4.7. Study Limitations

4.8. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parul, F.; Ratnani, T.; Subramani, S.; Bhatia, H.; Ashmawy, R.E.; Nair, N.; Manchanda, K.; Anyagwa, O.E.; Kaka, N.; Patel, N.; et al. Anticoagulation in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease: A Critical Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siontis, K.C.; Zhang, X.; Eckard, A.; Bhave, N.; Schaubel, D.E.; He, K.; Tilea, A.; Stack, A.G.; Balkrishnan, R.; Yao, X.; et al. Outcomes Associated With Apixaban Use in Patients With End-Stage Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation in the United States. Circulation 2018, 138, 1519–1529, Erratum in Circulation 2018, 138, e425. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tuta, L.; Stanigut, A.; Campineanu, B.; Pana, C. Novel Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Severe Chronic Kidney Disease, a Real Challenge. In Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- Stanifer, J.W.; Pokorney, S.D.; Chertow, G.M.; Hohnloser, S.H.; Wojdyla, D.M.; Garonzik, S.; Byon, W.; Hijazi, Z.; Lopes, R.D.; Alexander, J.H.; et al. Apixaban Versus Warfarin in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. Circulation 2020, 141, 1384–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atreja, N.; Johannesen, K.; Subash, R.; Bektur, C.; Hagan, M.; Hines, D.M.; Dunnett, I.; Stawowczyk, E. US cost-effectiveness analysis of apixaban compared with warfarin, dabigatran and rivaroxaban for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, focusing on equal value of life years and health years in total. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2025, 14, e240163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Granger, C.B.; Alexander, J.H.; McMurray, J.J.; Lopes, R.D.; Hylek, E.M.; Hanna, M.; Al-Khalidi, H.R.; Ansell, J.; Atar, D.; Avezum, A.; et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnelli, G.; Buller, H.R.; Cohen, A.; Curto, M.; Gallus, A.S.; Johnson, M.; Masiukiewicz, U.; Pak, R.; Thompson, J.; Raskob, G.E.; et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingason, A.B.; Hreinsson, J.P.; Agustsson, A.S.; Lund, S.H.; Rumba, E.; Palsson, D.A.; Reynisson, I.E.; Gudmundsdottir, B.R.; Onundarson, P.T.; Bjornsson, E.S. Comparison of the effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants: A nationwide propensity score-weighted study. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 2564–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ellenbogen, M.I.; Ardeshirrouhanifard, S.; Segal, J.B.; Streiff, M.B.; Deitelzweig, S.B.; Brotman, D.J. Safety and effectiveness of apixaban versus warfarin for acute venous thromboembolism in patients with end-stage kidney disease: A national cohort study. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 17, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cohen, A.T.; Sah, J.; Dhamane, A.D.; Lee, T.; Rosenblatt, L.; Hlavacek, P.; Emir, B.; Delinger, R.; Yuce, H.; Luo, X. Effectiveness and Safety of Apixaban versus Warfarin in Venous Thromboembolism Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 122, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frost, C.; Song, Y.; Barrett, Y.C.; Wang, J.; Pursley, J.; Boyd, R.A.; LaCreta, F. A randomized direct comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of apixaban and rivaroxaban. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 6, 179–187, Erratum in Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 10, 71. https://doi.org/10.2147/CPAA.S168295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vio, R.; Proietti, R.; Rigato, M.; Calò, L.A. Clinical Evidence for the Choice of the Direct Oral Anticoagulant in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation According to Creatinine Clearance. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suliman, I.L.; Panculescu, F.G.; Cimpineanu, B.; Popescu, S.; Fasie, D.; Cozaru, G.C.; Gafar, N.; Tuta, L.-A.; Alexandru, A. The Interplay of Cardiovascular Comorbidities and Anticoagulation Therapy in ESRD Patients on Haemodialysis—The South-Eastern Romanian Experience. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khwaja, A. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2012, 120, c179–c184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kister, T.S.; Remmler, J.; Schmidt, M.; Federbusch, M.; Eckelt, F.; Isermann, B.; Richter, H.; Wehner, M.; Krause, U.; Halbritter, J.; et al. Acute kidney injury and its progression in hospitalized patients-Results from a retrospective multicentre cohort study with a digital decision support system. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Givens, G.; Neu, D.; Marler, J. The Risk of Major Bleeding With Apixaban Administration in Patients With Acute Kidney Injury. Ann. Pharmacother. 2023, 57, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarka, F.; Tayler-Gomez, A.; Ducruet, T.; Duca, A.; Albert, M.; Bernier-Jean, A.; Bouchard, J. Risk of incident bleeding after acute kidney injury: A retrospective cohort study. J. Crit. Care. 2020, 59, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.S.; Lin, M.S.; Wu, V.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Chang, J.J.; Chu, P.H.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Chen, M.C. Differential Presentations of Arterial Thromboembolic Events Between Venous Thromboembolism and Atrial Fibrillation Patients. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 775564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shariff, N.; Aleem, A.; Singh, M.; ZLi, Y.; JSmith, S. AF and Venous Thromboembolism—Pathophysiology, Risk Assessment and CHADS-VASc score. J. Atr. Fibrillation 2012, 5, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vu, A.; Qu, T.T.; Ryu, R.; Nandkeolyar, S.; Jacobson, A.; Hong, L.T. Critical Analysis of Apixaban Dose Adjustment Criteria. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2021, 27, 10760296211021158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Eliquis (Apixaban) [Package Insert]; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pokorney, S.D.; Chertow, G.M.; Al-Khalidi, H.R.; Gallup, D.; Dignacco, P.; Mussina, K.; Bansal, N.; Gadegbeku, C.A.; Garcia, D.A.; Garonzik, S.; et al. Apixaban for Patients With Atrial Fibrillation on Hemodialysis: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation 2022, 146, 1735–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinecke, H.; Engelbertz, C.; Bauersachs, R.; Breithardt, G.; Echterhoff, H.H.; Gerß, J.; Haeusler, K.G.; Hewing, B.; Hoyer, J.; Juergensmeyer, S.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Apixaban With the Vitamin K Antagonist Phenprocoumon in Patients on Chronic Hemodialysis: The AXADIA-AFNET 8 Study. Circulation 2023, 147, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffel, J.; Collins, R.; Antz, M.; Cornu, P.; Desteghe, L.; Haeusler, K.G.; Oldgren, J.; Reinecke, H.; Roldan-Schilling, V.; Rowell, N.; et al. 2021 European Heart Rhythm Association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2021, 23, 1612–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eikelboom, J.W.; Connolly, S.J.; Brueckmann, M.; Granger, C.B.; Kappetein, A.P.; Mack, M.J.; Blatchford, J.; Devenny, K.; Friedman, J.; Guiver, K.; et al. RE-ALIGN Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, S.J.; Karthikeyan, G.; Ntsekhe, M.; Haileamlak, A.; El Sayed, A.; El Ghamrawy, A.; Damasceno, A.; Avezum, A.; Dans, A.M.L.; Gitura, B.; et al. INVICTUS Investigators. Rivaroxaban in rheumatic heart disease-associated atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, H.; Brand, E.; Mesters, R.; Schaebitz, W.R.; Fisher, M.; Pavenstaedt, H.; Breithardt, G. Dilemmas in the management of atrial fibrillation in chronic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KDIGO Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for CKD management. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 102, S1–S150. [Google Scholar]

- Domienik-Karłowicz, J.; Tronina, O.; Lisik, W.; Durlik, M.; Pruszczyk, P. The use of anticoagulants in chronic kidney disease: Common point of view of cardiologists and nephrologists. Cardiol. J. 2020, 27, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variable | Apixaban (n = 50) | Acenocoumarol (n = 43) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.6 ± 7.6 | 66.9 ± 10.6 | 0.47 |

| Male (%) | 52 | 49 | 0.74 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 14.1 ± 8.3 | 12.8 ± 5.9 | 0.55 |

| CKD stage 5 (%) | 72 | 70 | 0.81 |

| Hypertension (%) | 92 | 93 | 0.88 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 44 | 51 | 0.49 |

| Ischemic heart disease (%) | 36 | 42 | 0.61 |

| Heart failure (%) | 40 | 49 | 0.42 |

| Stroke/TIA history (%) | 26 | 30 | 0.70 |

| Hemodialysis (%) | 40 | 42 | p = 0.82 |

| Parameter | Apixaban (n = 50) | Acenocoumarol (n = 43) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.2 ± 1.8 | 10.4 ± 1.7 | 0.04 * |

| Serum Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 0.02 * |

| C-reactive protein (CRP, mg/L) | 8.9 ± 6.4 | 13.7 ± 9.5 | 0.03 * |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL) | 6.1 ± 2.3 | 7.3 ± 2.8 | 0.01 * |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 14.4 ± 7.8 | 12.9 ± 5.6 | 0.27 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 325 ± 118 | 348 ± 132 | 0.41 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 427 ± 91 | 458 ± 102 | 0.16 |

| INR (VKA only) | — | 2.8 ± 0.7 | — |

| HAS-BLED score | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 0.56 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 5.7 ± 1.0 | 5.9 ± 1.3 | 0.61 |

| Event Type | Apixaban (n = 50) | Acenocoumarol (n = 43) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major bleeding | 4 (8.0%) | 5 (11.6%) | 0.64 |

| Minor bleeding | 4 (8.0%) | 18 (41.9%) | 0.04 |

| Total bleeding events | 7 (16.0%) | 15 (53.5%) | 0.02 |

| Event | Dialysis (n = 38) | Non-Dialysis (n = 55) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major bleeding (%) | 13.2 | 7.4 | 0.31 |

| Minor bleeding (%) | 18.4 | 10.9 | 0.25 |

| Overdose-related (%) | 10.5 | 1.8 | 0.02 |

| Thromboembolic (%) | 0 | 0 | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suliman, I.L.; Tuta, L.-A.; Panculescu, F.G.; Alexandru, A.; Fasie, D.; Cimpineanu, B.; Cozaru, G.C.; Popescu, S.; Enache, F.-D.; Manac, I.; et al. Comparative Outcomes of Apixaban and Acenocoumarol in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation: A Retrospective Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8860. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248860

Suliman IL, Tuta L-A, Panculescu FG, Alexandru A, Fasie D, Cimpineanu B, Cozaru GC, Popescu S, Enache F-D, Manac I, et al. Comparative Outcomes of Apixaban and Acenocoumarol in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation: A Retrospective Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8860. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248860

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuliman, Ioana Livia, Liliana-Ana Tuta, Florin Gabriel Panculescu, Andreea Alexandru, Dragos Fasie, Bogdan Cimpineanu, Georgeta Camelia Cozaru, Stere Popescu, Florin-Daniel Enache, Iulian Manac, and et al. 2025. "Comparative Outcomes of Apixaban and Acenocoumarol in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation: A Retrospective Observational Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8860. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248860

APA StyleSuliman, I. L., Tuta, L.-A., Panculescu, F. G., Alexandru, A., Fasie, D., Cimpineanu, B., Cozaru, G. C., Popescu, S., Enache, F.-D., Manac, I., Chisnoiu, T., Alexandrescu, L., & Bordeianu, I. (2025). Comparative Outcomes of Apixaban and Acenocoumarol in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation: A Retrospective Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8860. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248860