Outcomes of Liver Transplantation in Incidental Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: An Exceptional Perspective from a Single-Center Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection and Follow-Up

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

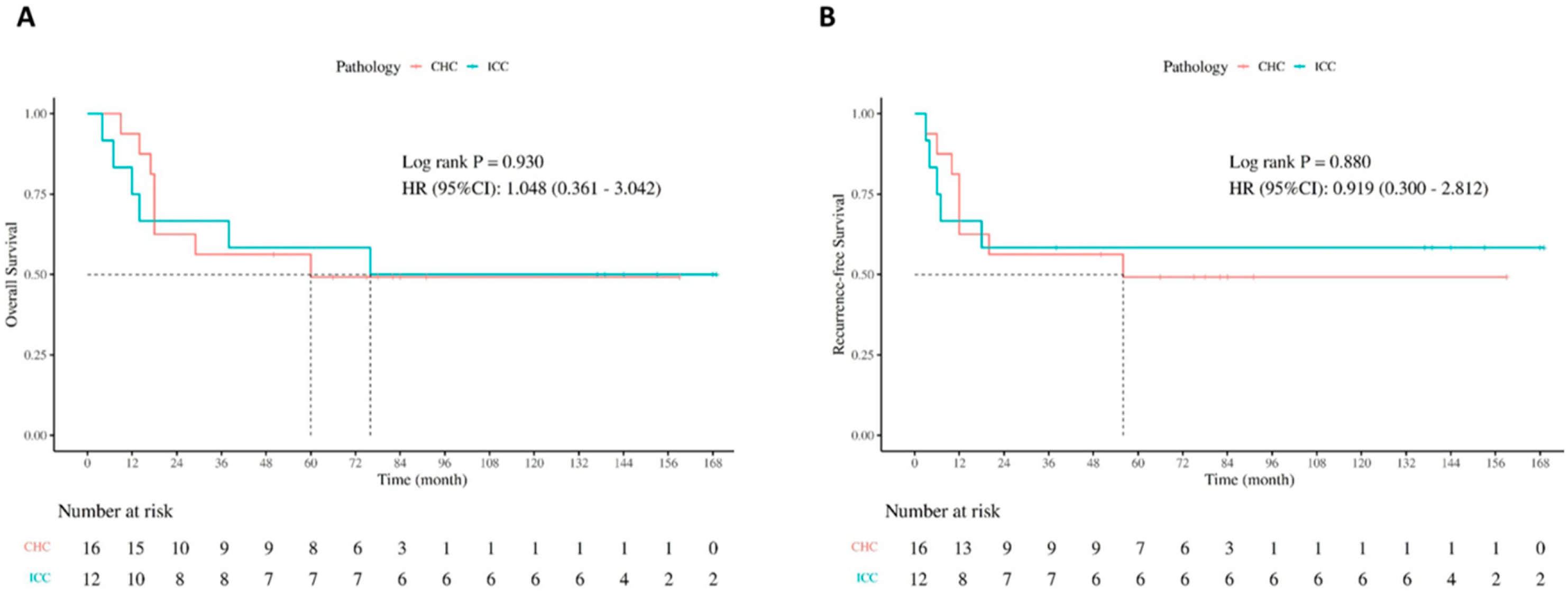

3.2. Analysis Based on Tumor Types

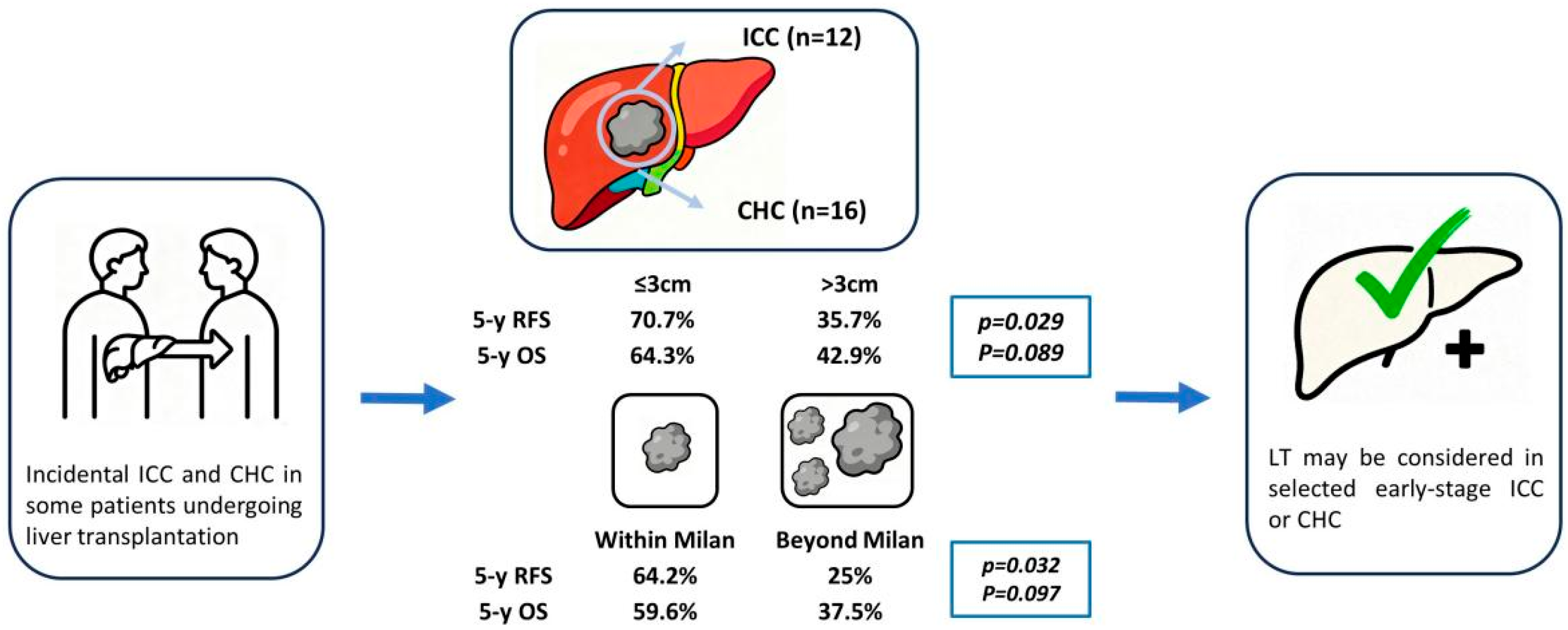

3.3. Analysis Based on Tumor Size

3.4. Analysis Based on Milan Criteria

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moris, D.; Palta, M.; Kim, C.; Allen, P.J.; Morse, M.A.; Lidsky, M.E. Advances in the treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: An overview of the current and future therapeutic landscape for clinicians. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL-ILCA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarathi, R.; Peshin, S.; Zhang, X.; Bachini, M.; Meeks, M.N.; Shroff, R.T.; Pillai, A. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Insights on molecular testing, targeted therapies, and future directions from a multidisciplinary panel. Hepatol. Commun. 2025, 9, e0743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuzillet, C.; Decraecker, M.; Larrue, H.; Ntanda-Nwandji, L.C.; Barbier, L.; Barge, S.; Belle, A.; Chagneau, C.; Edeline, J.; Guettier, C.; et al. Management of intrahepatic and perihilar cholangiocarcinomas: Guidelines of the French Association for the Study of the Liver (AFEF). Liver Int. 2024, 44, 2517–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Schneider, J.S.; Ben Khaled, N.; Schirmacher, P.; Seifert, C.; Frey, L.; He, Y.; Geier, A.; De Toni, E.N.; Zhang, C.; et al. Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: Biology, Diagnosis, and Management. Liver Cancer 2024, 13, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzu, S.; Szodorai, R.; Jung, I.; Banias, L. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: From genesis to molecular pathways and therapeutic strategies. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, M.; Veerankutty, F.H.; Rammohan, A.; Rela, M. Combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma: A clinicopathological update. World J. Hepatol. 2024, 16, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapisochin, G.; Ivanics, T.; Heimbach, J. Liver Transplantation for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Ready for Prime Time? Hepatology 2022, 75, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, S.; Saharia, A.; Ghobrial, R.M. Liver transplantation and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Time to go forward again? Curr. Opin. Organ. Transplant. 2022, 27, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achurra, P.; Fernandes, E.; O’Kane, G.; Grant, R.; Cattral, M.; Sapisochin, G. Liver transplantation for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Who, when and how. Curr. Opin. Organ. Transplant. 2024, 29, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapisochin, G.; Rodriguez de Lope, C.; Gastaca, M.; Ortiz de Urbina, J.; Suarez, M.A.; Santoyo, J.; Castroagudin, J.F.; Varo, E.; Lopez-Andujar, R.; Palacios, F.; et al. “Very early” intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in cirrhotic patients: Should liver transplantation be reconsidered in these patients? Am. J. Transplant. 2014, 14, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunsford, K.E.; Javle, M.; Heyne, K.; Shroff, R.T.; Abdel-Wahab, R.; Gupta, N.; Mobley, C.M.; Saharia, A.; Victor, D.W.; Nguyen, D.T.; et al. Liver transplantation for locally advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma treated with neoadjuvant therapy: A prospective case-series. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martin, E.; Rayar, M.; Golse, N.; Dupeux, M.; Gelli, M.; Gnemmi, V.; Allard, M.A.; Cherqui, D.; Sa Cunha, A.; Adam, R.; et al. Analysis of Liver Resection Versus Liver Transplantation on Outcome of Small Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma in the Setting of Cirrhosis. Liver Transplant. 2020, 26, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childers, B.G.; Denbo, J.W.; Kim, R.D.; Hoffe, S.E.; Glushko, T.; Qayyum, A.; Anaya, D.A. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Role of imaging as a critical component for multi-disciplinary treatment approach. Abdom. Radiol. 2025, 50, 4110–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, R.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Yang, C.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zeng, M. “Very early” intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (≤ 2.0 cm): MRI manifestation and prognostic potential. Clin. Radiol. 2024, 79, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, N.Z.; Hakeem, A.R.; Faulkes, R.; James, F.; Mason, L.; Masson, S.; Powell, J.; Rowe, I.; Shetty, S.; Jones, R.; et al. Outcomes After Liver Transplantation With Incidental Cholangiocarcinoma. Transpl. Int. 2022, 35, 10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Moreno, V.; Justo-Alonso, I.; Fernandez-Fernandez, C.; Rivas-Duarte, C.; Aranda-Romero, B.; Loinaz-Segurola, C.; Jimenez-Romero, C.; Caso-Maestro, O. “Long-term follow-up of liver transplantation in incidental intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma”. Cir. Esp. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 101, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, T.; Eguchi, S.; Yoshizumi, T.; Akamatsu, N.; Kaido, T.; Hamada, T.; Takamura, H.; Shimamura, T.; Umeda, Y.; Shinoda, M.; et al. Incidental intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients undergoing liver transplantation: A multi-center study in Japan. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2021, 28, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapisochin, G.; de Lope, C.R.; Gastaca, M.; de Urbina, J.O.; Lopez-Andujar, R.; Palacios, F.; Ramos, E.; Fabregat, J.; Castroagudin, J.F.; Varo, E.; et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma in patients undergoing liver transplantation: A Spanish matched cohort multicenter study. Ann. Surg. 2014, 259, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, S.; Kulik, L.; D’Allessio, A.; De Martin, E.; Hakeem, A.R.; Lewinska, M.; Lindsey, S.; Liu, K.; Maravic, Z.; Patel, M.S.; et al. The 2024 ILTS-ILCA consensus recommendations for liver transplantation for HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Transplant. 2025, 31, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapisochin, G.; Facciuto, M.; Rubbia-Brandt, L.; Marti, J.; Mehta, N.; Yao, F.Y.; Vibert, E.; Cherqui, D.; Grant, D.R.; Hernandez-Alejandro, R.; et al. Liver transplantation for “very early” intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: International retrospective study supporting a prospective assessment. Hepatology 2016, 64, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Che, F.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, B. Role of noninvasive imaging in the evaluation of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: From diagnosis and prognosis to treatment response. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 15, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mar, W.A.; Chan, H.K.; Trivedi, S.B.; Berggruen, S.M. Imaging of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Semin. Ultrasound CT MR 2021, 42, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazian, H.; Mirza-Aghazadeh-Attari, M.; Borhani, A.; Mohseni, A.; Madani, S.P.; Ansari, G.; Pawlik, T.M.; Kamel, I.R. Multimodality imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 128, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samban, S.S.; Hari, A.; Nair, B.; Kumar, A.R.; Meyer, B.S.; Valsan, A.; Vijayakurup, V.; Nath, L.R. An Insight Into the Role of Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) in the Development and Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol. Biotechnol. 2024, 66, 2697–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, A.; Mehta, R.; Sahara, K.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Paredes, A.Z.; Farooq, A.; Hyer, J.M.; Endo, I.; Shen, F.; Guglielmi, A.; et al. The Impact of Preoperative CA19-9 and CEA on Outcomes of Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 2888–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubner, M.G.; Larison, W.G.; Watson, R.; Wells, S.A.; Ziemlewicz, T.J.; Lubner, S.J.; Pickhardt, P.J. Efficacy of percutaneous image-guided biopsy for diagnosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Abdom. Radiol. 2022, 47, 2647–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N.; Connor, A.A.; Saharia, A.; Kodali, S.; Elaileh, A.; Patel, K.; Semaan, S.; Basra, T.; Victor, D.W., 3rd; Simon, C.J.; et al. Neoadjuvant Multiagent Systemic Therapy Approach to Liver Transplantation for Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma. Transplant. Direct 2025, 11, e1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, R.R.; Javle, M.; Kodali, S.; Saharia, A.; Mobley, C.; Heyne, K.; Hobeika, M.J.; Lunsford, K.E.; Victor, D.W., 3rd; Shetty, A.; et al. Survival following liver transplantation for locally advanced, unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, M.; Sposito, C.; Bongini, M.A.; Cascella, T.; Flores, M.; Maccauro, M.; Chiesa, C.; Niger, M.; Pietrantonio, F.; Leoncini, G.; et al. Liver Transplantation for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma After Chemotherapy and Radioembolization: An Intention-To-Treat Study. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 13641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Butler, J.R.; Noguchi, D.; Ha, M.; Aziz, A.; Agopian, V.G.; DiNorcia, J., 3rd; Yersiz, H.; Farmer, D.G.; Busuttil, R.W.; et al. A 3-Decade, Single-Center Experience of Liver Transplantation for Cholangiocarcinoma: Impact of Era, Tumor Size, Location, and Neoadjuvant Therapy. Liver Transplant. 2022, 28, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeline, J.; Lamarca, A.; McNamara, M.G.; Jacobs, T.; Hubner, R.A.; Palmer, D.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; Johnson, P.; Guiu, B.; Valle, J.W. Locoregional therapies in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review and pooled analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2021, 99, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.; Makary, M.S.; Beal, E.W. Locoregional Therapy for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhu, W.W.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J.B.; Wang, S.H.; Bai, F.M.; Li, T.E.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, X.; et al. Driver mutations of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma shape clinically relevant genomic clusters with distinct molecular features and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Theranostics 2022, 12, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Sahai, V.; Hollebecque, A.; Vaccaro, G.; Melisi, D.; Al-Rajabi, R.; Paulson, A.S.; Borad, M.J.; Gallinson, D.; Murphy, A.G.; et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Lu, D.; Chen, R.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, S.; Cui, P.; Song, G.; Rao, D.; et al. Proteogenomic characterization identifies clinically relevant subgroups of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 70–87 e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andraus, W.; Ochoa, G.; de Martino, R.B.; Pinheiro, R.S.N.; Santos, V.R.; Lopes, L.D.; Arantes Junior, R.M.; Waisberg, D.R.; Santana, A.C.; Tustumi, F.; et al. The role of living donor liver transplantation in treating intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1404683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauchfuss, F.; Ali-Deeb, A.; Rohland, O.; Dondorf, F.; Ardelt, M.; Settmacher, U. Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1932–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, M.M.; Dunne, R.F.; Melaragno, J.I.; Chavez-Villa, M.; Hezel, A.; Liao, X.; Ertreo, M.; Al-Judaibi, B.; Orloff, M.; Hernandez-Alejandro, R.; et al. Neoadjuvant pemigatinib as a bridge to living donor liver transplantation for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR2 gene rearrangement. Am. J. Transplant. 2025, 25, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total (n = 28) | CHC (n = 16) | ICC (n = 12) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52 (35–73) | 53 (35–62) | 51 (39–73) | 0.625 |

| Gender, Male | 23 (82.1) | 13 (81.3) | 10 (83.3) | 1.000 |

| Presence of HBV infection | 22 (78.6) | 11 (68.8) | 11 (91.7) | 0.196 |

| Presence of cirrhosis | 21 (75.0) | 12 (75.0) | 9(75.0) | 1.000 |

| AFP level (ng/mL) | 107.4 (4.1–9950) | 193.0 (4.1–9950) | 25.5 (4.8–3000) | 0.302 |

| CA19-9 level (U/mL) | 25.2 (2.0–325) | 18.9 (2–82) | 42.3 (14.5–325) | 0.007 |

| Maximum tumor size (cm) | 3.3 (0.8–12.0) | 3.5 (1.5–10.0) | 3 (0.8–12.0) | |

| Tumor number, Single | 20 (71.4) | 12 (75) | 8 (66.7) | 0.691 |

| Presence of micro-vascular invasion | 11 (39.3) | 7 (43.8) | 4 (33.3) | 0.705 |

| Differentiation | 0.242 | |||

| Well | 16 (57.1) | 11 (68.8) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Moderate | 8 (28.6) | 4 (25.0) | 4 (33.3) | |

| Poor | 4 (14.3) | 1 (6.2) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Presence of perineural invasion | 2 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (8.3) | 1.000 |

| Within Milan criteria | 20 (71.4) | 11 (68.8) | 9 (75.0) | 1.000 |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| I | 12 (42.9) | 7 (43.8) | 5 (41.7) | 0.680 |

| II | 15 (53.6) | 9 (56.2) | 6 (50.0) | |

| III | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | |

| Type | ||||

| Incidental tumor | 3 (10.7) | 0 | 3 (25.0) | 0.067 |

| Presumed HCC | 25 (89.3) | 16 (100.0) | 9 (75.0) | |

| Preoperative treatment | 10 (35.7) | 7 (43.8) | 3 (25.0) | 0.434 |

| Postoperative adjuvant therapy | 5 (17.9) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (16.8) | 1.000 |

| ICC | CHC | p-Value | |||||

| 1-Year | 3-Year | 5-Year | 1-Year | 3-Year | 5-Year | ||

| RFS% | 66.7 | 58.3 | 58.3 | 62.5 | 56.3 | 49.2 | 0.880 |

| OS% | 75 | 66.7 | 58.3 | 93.8 | 62.5 | 49.2 | 0.930 |

| <3 cm | ≥3 cm | p-value | |||||

| 1-year | 3-year | 5-year | 1-year | 3-year | 5-year | ||

| RFS% | 85.7 | 78.6 | 70.7 | 42.9 | 35.7 | 35.7 | 0.029 |

| OS% | 92.9 | 78.6 | 64.3 | 78.6 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 0.089 |

| Within Milan criteria | Beyond Milan criteria | p-value | |||||

| 1-year | 3-year | 5-year | 1-year | 3-year | 5-year | ||

| RFS% | 75 | 70 | 64.2 | 37.5 | 25 | 25 | 0.032 |

| OS% | 90 | 75 | 59.6 | 75 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 0.097 |

| ICC (n = 12) | CHC (n = 16) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Size > 3 cm (n = 5) | Size ≤ 3 cm (n = 7) | p-Value | Size > 3 cm (n = 9) | Size ≤ 3 cm (n = 7) | p-Value |

| Age, years | 50 (49–58) | 52 (39–73) | 1.000 | 52 (35–62) | 54 (46–61) | 0.490 |

| Gender, Male | 4 (80.0) | 6 (85.7) | 1.000 | 6 (66.7) | 7 (100.0) | 0.212 |

| Presence of HBV infection | 5 (100.0) | 6 (85.7) | 1.000 | 6 (66.7) | 5 (71.4) | 1.000 |

| Presence of cirrhosis | 4 (80.0) | 5 (71.4) | 1.000 | 6 (66.7) | 6 (85.7) | 0.585 |

| AFP level (ng/mL) | 49.8 (18–3000) | 7.1 (4.8–1429.1) | 0.149 | 235 (5.1–9950) | 186 (4.1–458.0) | 0.299 |

| CA19-9 level (U/mL) | 51.9 (39–325) | 36.0 (14.5–165.6) | 0.149 | 15 (2–63) | 21 (3.1–82.0) | 0.681 |

| Tumor number, Single | 3 (60.0) | 5 (71.4) | 1.000 | 7 (77.8) | 5 (71.4) | 1.000 |

| Presence of micro-vascular invasion | 3 (60.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0.222 | 5 (55.6) | 2 (28.6) | 0.358 |

| Differentiation | 0.773 | 1.000 | ||||

| Well | 2 (40.0) | 3 (42.9) | 6 (66.7) | 5 (71.4) | ||

| Moderate | 1 (20.0) | 3 (42.9) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (28.6) | ||

| Poor | 2 (40.0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (22.2) | 0 | ||

| Presence of perineural invasion | 1 (20.0) | 0 | 0.417 | 1 (11.1) | 0 | |

| Within Milan criteria | 2 (40.0) | 7 (100.0) | 0.045 | 4 (44.4) | 7 (100.0) | 0.034 |

| Tumor stage | 0.369 | |||||

| I | 1 (20.0) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (57.1) | 0.615 | |

| II | 3 (60.0) | 3 (42.9) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| III | 1 (20.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Preoperative treatment | 2 (40.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0.523 | 4 (44.4) | 3 (42.9) | 1.000 |

| Postoperative adjuvant therapy | 2 (40.0) | 0 | 0.152 | 2 (22.2) | 1 (14.3) | 1.000 |

| ICC (n = 12) | CHC (n = 16) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Within Milan Criteria (n = 9) | Beyond Milan Criteria (n = 3) | p-Value | Within Milan Criteria (n = 11) | Beyond Milan Criteria (n = 5) | p-Value |

| Age, years | 49 (39–73) | 51 (50–58) | 0.516 | 54 (37–62) | 52 (35–59) | 0.733 |

| Gender, Male | 8 (88.9) | 2 (66.7) | 0.455 | 9 (81.8) | 4 (80.0) | 1.000 |

| Presence of HBV infection | 8 (88.9) | 3 (100) | 1.000 | 7 (63.6) | 4 (80.0) | 1.000 |

| Presence of cirrhosis | 7 (77.8) | 2 (66.7) | 1.000 | 9 (81.8) | 3 (60.0) | 0.547 |

| AFP level (ng/mL) | 19.5 (4.8–1429.1) | 769.3 (18–3000) | 0.209 | 186 (4.1–458) | 485 (100–9950) | 0.090 |

| CA19-9 level (U/mL) | 39.0 (14.5–165.6) | 65.3 (51.9–325) | 0.036 | 16.7 (2–82) | 25.0 (10.3–63) | 0.441 |

| Maximum tumor size (cm) | 2.5 (0.8–4.0) | 10 (10–12) | 0.015 | 3.00 (1.5–4.5) | 6.50 (5–10) | 0.002 |

| Tumor number, Single | 7 (77.8) | 1 (33.3) | 0.236 | 9 (81.8) | 3 (60.0) | 0.547 |

| Presence of micro-vascular invasion | 2 (22.2) | 2 (66.7) | 0.236 | 5 (45.5) | 2 (40.0) | 1.000 |

| Differentiation | 1.000 | 0.471 | ||||

| Well | 4 (44.5) | 1 (33.3) | 8 (72.7) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| Moderate | 3 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Poor | 2 (22.2) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Presence of perineural invasion | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 1.000 | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Tumor stage | 0.159 | 1.000 | ||||

| I | 5 (55.6) | 0 | 5 (45.5) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| II | 4 (44.4) | 2 (66.7) | 6 (54.5) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| III | 0 | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Preoperative treatment | 2 (22.2) | 1 (33.3) | 1.000 | 4 (36.4) | 3 (60.0) | 0.596 |

| Postoperative adjuvant therapy | 1 (11.1) | 1 (33.3) | 0.455 | 1 (9.1) | 2 (40.0) | 0.214 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, L.; Xia, Q.; Sha, M. Outcomes of Liver Transplantation in Incidental Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: An Exceptional Perspective from a Single-Center Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248857

Ma L, Xia Q, Sha M. Outcomes of Liver Transplantation in Incidental Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: An Exceptional Perspective from a Single-Center Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248857

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Lijie, Qiang Xia, and Meng Sha. 2025. "Outcomes of Liver Transplantation in Incidental Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: An Exceptional Perspective from a Single-Center Experience" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248857

APA StyleMa, L., Xia, Q., & Sha, M. (2025). Outcomes of Liver Transplantation in Incidental Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: An Exceptional Perspective from a Single-Center Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248857