Impact of an Interdisciplinary Care Program on Health Outcomes in Older Patients with Multimorbidity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Multimorbidity Care Program

2.2. Study Population and Eligibility

2.3. Events of Interest and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

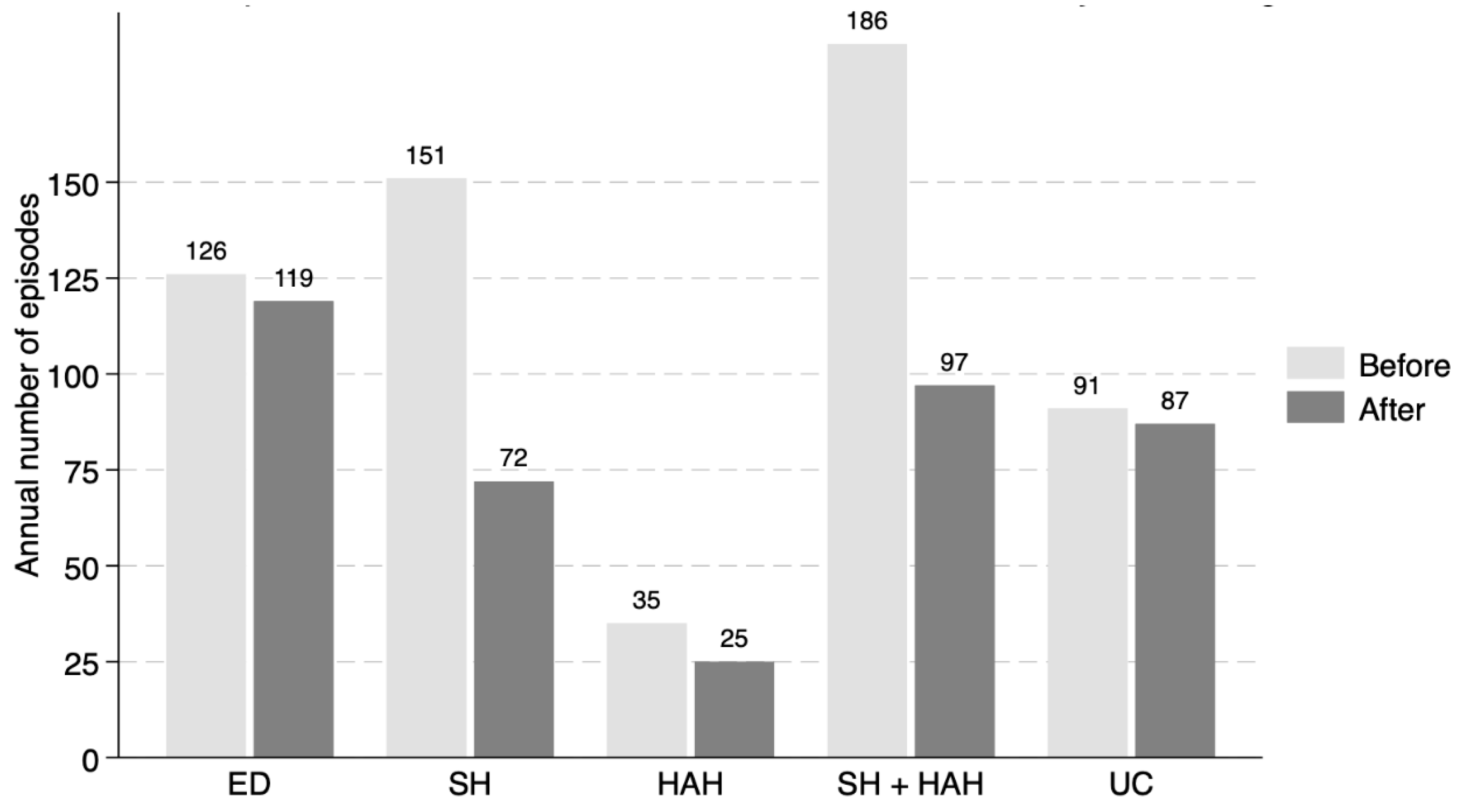

| ED | Emergency Department visits |

| SH | Standard Hospitalization |

| HAH | Hospital-at-home care |

| UC | Unnecessary Medical Consultations |

References

- INEbase/Demografía y Población/Cifras de Población y Censos Demográficos/Proyecciones de Población/Últimos Datos. INE. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176953&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735572981 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Melis, R.; Marengoni, A.; Angleman, S.; Fratiglioni, L. Incidence and predictors of multimorbidity in the elderly: A population-based longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, M.; Stewart, M.; Poitras, M.E.; Almirall, J.; Maddocks, H. A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: Toward a more uniform methodology. Ann. Fam. Med. 2012, 10, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marengoni, A.; Angleman, S.; Melis, R.; Mangialasche, F.; Karp, A.; Garmen, A.; Meinow, B.; Fratiglioni, L. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Lee, D.T.F.; Wang, X.; Chair, S.Y. Effects of a nurse-led medication self-management intervention on medication adherence and health outcomes in older people with multimorbidity: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 134, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobili, A.; Marengoni, A.; Tettamanti, M.; Salerno, F.; Pasina, L.; Franchi, C.; Iorio, A.; Marcucci, M.; Corrao, S.; Licata, G.; et al. Association between clusters of diseases and polypharmacy in hospitalized elderly patients: Results from the REPOSI study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 22, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Fried, T.R.; Boyd, C.M. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition—Multimorbidity. JAMA 2012, 307, 2493–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onder, G.; Palmer, K.; Navickas, R.; Jurevičienė, E.; Mammarella, F.; Strandzheva, M.; Mannucci, P.; Pecorelli, S.; Marengoni, A. Time to face the challenge of multimorbidity. A European perspective from the joint action on chronic diseases and promoting healthy ageing across the life cycle (JA-CHRODIS). Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 26, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S.; Bolshakova, M.; Hochman, M.; Jimenez, E.; Thompson, G.; Motala, A.; Ganz, D.A.; Gabrielian, S.; Edwards, S.; Zenner, J.; et al. Caring for high-need patients. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.; Marengoni, A.; Forjaz, M.J.; Jureviciene, E.; Laatikainen, T.; Mammarella, F.; Muth, C.; Navickas, R.; Prados-Torres, A.; Rijken, M.; et al. Multimorbidity care model: Recommendations from the consensus meeting of the Joint Action on Chronic Diseases and Promoting Healthy Ageing across the Life Cycle (JA-CHRODIS). Health Policy 2018, 122, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skou, S.T.; Mair, F.S.; Fortin, M.; Guthrie, B.; Nunes, B.P.; Miranda, J.J.; Boyd, C.M.; Pati, S.; Mtenga, S.; Smith, S.M. Multimorbidity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollero-Baturone, M.; Álvarez, M.; Barón-Franco, B.; Bernabéu, M.; Codina, A.; Fernández, A.; Garrido, E. Atención al Paciente Pluripatológico. Proceso Asistencial Integrado, 2nd ed.; Consejería de Salud de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/export/drupaljda/salud_5af1956d9ec34_pluri.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Levine, D.M.; Ouchi, K.; Blanchfield, B.; Saenz, A.; Burke, K.; Paz, M.; Diamond, K.; Pu, C.T.; Schnipper, J.L. Hospital-Level Care at Home for Acutely Ill Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, M.Q.; Lim, C.W.; Lai, Y.F. Comparison of Hospital-at-Home models: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.M.; Wallace, E.; O’Dowd, T.; Fortin, M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 1, CD006560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohwer, A.; Toews, I.; Uwimana-Nicol, J.; Nyirenda, J.L.; Niyibizi, J.B.; Akiteng, A.R.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Bavuma, C.M.; Kredo, T.; Young, T. Models of integrated care for multi-morbidity assessed in systematic reviews: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas-Nava, L.A.; Garduño-Espinosa, J.; Mireles Dorantes, J.M.; Medina-Campos, R.; García-Peña, M.C. Models of comprehensive care for older persons with chronic diseases: A systematic review with a focus on effectiveness. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, L.S.; Marton, K.I.; Barbaccia, J.C.; Randolph, J. Physician, nurse, and social worker collaboration in primary care for chronically ill seniors. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 1825–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, P.; Schellevis, F.G.; Rijken, M. Health-related needs of people with multiple chronic diseases: Differences and underlying factors. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazya, A.L.; Garvin, P.; Ekdahl, A.W. Outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment: Effects on frailty and mortality in old people with multimorbidity and high health care utilization. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo Maroto, I.; Cubo Romano, P.; Mafé Nogueroles, M.C.; Matesanz-Fernández, M.; Pérez-Belmonte, L.M.; Criado, I.S.; Gómez-Huelgas, R.; Manglano, J.D.; Focus Group on Aging of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine and the Working Group on Polypathology and Advanced Age. Recommendations on the comprehensive, multidimensional assessment of hospitalized elderly people. Position of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2021, 221, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, R.; McDonough, A.; Ellis, G.; Bennett, K.; O’Neill, D.; Robinson, D. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment for community-dwelling, high-risk, frail, older people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 5, CD012705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevirme, A.; Gokcay, G. The impact of an Education-Based Intervention Program (EBIP) on dyspnea and chronic self-care management among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. A randomized controlled study. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 1350–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Qu, Z.; Zheng, S. Effect of self-management intervention on prognosis of patients with chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markle-Reid, M.; Ploeg, J.; Fraser, K.D.; Fisher, K.A.; Bartholomew, A.; Griffith, L.E.; Miklavcic, J.; Gafni, A.; Thabane, L.; Upshur, R. Community Program Improves Quality of Life and Self-Management in Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus and Comorbidity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmond, P.; Grimes, T.C.; McDonnell, R.; Boland, F.; Hughes, C.; Fahey, T. Impact of medication reconciliation for improving transitions of care. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD010791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Silveira, E.; Fernandez-Villalba, E.M.; García-Mina Freire, M.; Albiñana Pérez, M.S.; Casajús Lagranja, M.P.; Peris Martí, J.F. The impact of Pharmacy Intervention on the treatment of elderly multi-pathological patients. Farm Hosp. 2015, 39, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.B.; McLachlan, A.J.; Brien, J.A.E. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciudad-Gutiérrez, P.; Del Valle-Moreno, P.; Lora-Escobar, S.J.; Guisado-Gil, A.B.; Alfaro-Lara, E.R. Electronic Medication Reconciliation Tools Aimed at Healthcare Professionals to Support Medication Reconciliation: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2023, 48, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, M.; Crisafulli, S.; Vitturi, G.; Besco, M.; Hinek, D.; Sartorio, A.; Tanara, V.; Spadacini, G.; Selleri, M.; Zanconato, V.; et al. Clinical impact of medication review and deprescribing in older inpatients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 3219–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.A.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Alqahtani, M.; E Barry, H.; Cadogan, C.; Rankin, A.; Patterson, S.M.; Kerse, N.; Cardwell, C.R.; Ryan, C.; et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 10, CD008165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 82.5 (7.3) |

| Female gender, % | 50 |

| Barthel index, mean (SD) | 78.6 (21.6) |

| Lawton scale, mean (SD) | 4.0 (2.5) |

| Dawnton scale, mean (SD) | 2.6 (1.1) |

| Chronic Pain, % | 24.5 |

| MNA SF index, mean (SD) | 10.2 (2.4) |

| Cognitive status (Pfeiffer scale) | |

| No cognitive impairment, % | 71.9 |

| Mild cognitive impairment, % | 15.6 |

| Severe cognitive impairment, % | 12.5 |

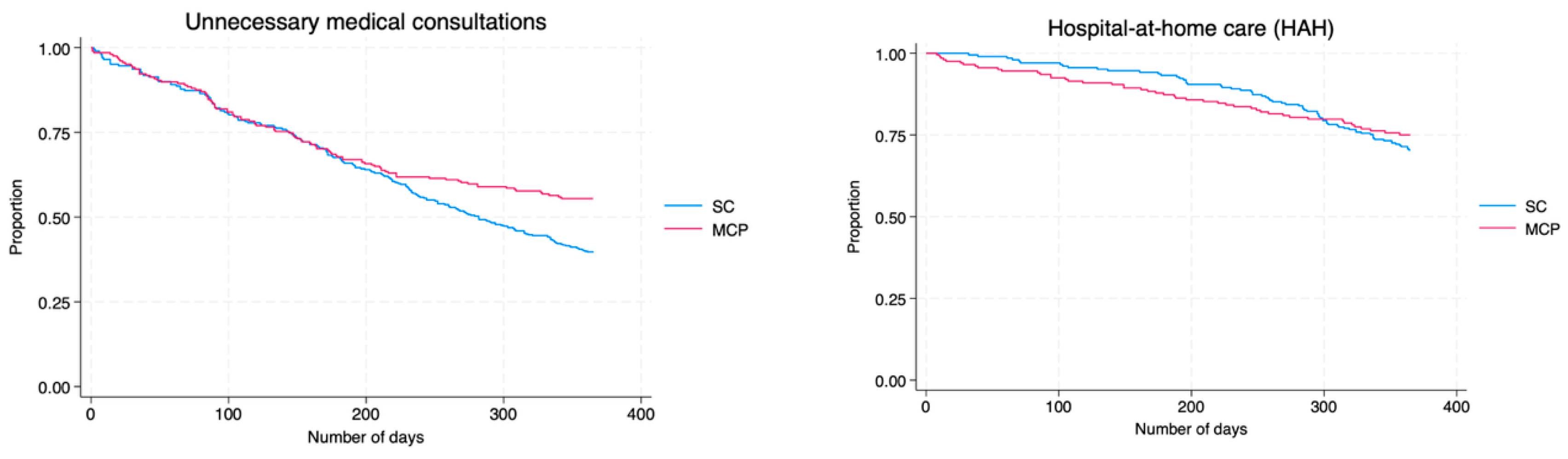

| Outcomes | HR (95% CI), Multimorbidity Care Program/Standard Care | p |

|---|---|---|

| Standard hospitalization | 0.54 (0.44–0.68) | <0.001 |

| Hospital-at-home care | 0.87 (0.54–1.38) | 0.545 |

| SH + HAH | 0.60 (0.47–0.75) | <0.001 |

| Emergency department visits | 0.74 (0.60–0.92) | 0.006 |

| Avoidable outpatient consultations | 0.66 (0.51–0.86) | 0.002 |

| Outcomes | Incidence Rate Ratios |

|---|---|

| Standard hospitalization (SH) | 0.51 (0.41–0.64) |

| Hospital-at-home care (HAH) | 0.84 (0.51–1.36) |

| SH + HAH | 0.58 (0.46–0.74) |

| Emergency department visits | 0.77 (0.62–0.95) |

| Avoidable outpatient consultations | 0.81 (0.64–1.03) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cubo-Romano, P.; García-de-la-Torre, P.; Medina-de-Campos, C.; Casado-López, I.; de-Castro-García, M.; Estrada-Santiago, A.; Majo-Carbajo, Y.; Núñez-Palomares, S.; Casas-Rojo, J.M. Impact of an Interdisciplinary Care Program on Health Outcomes in Older Patients with Multimorbidity. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248856

Cubo-Romano P, García-de-la-Torre P, Medina-de-Campos C, Casado-López I, de-Castro-García M, Estrada-Santiago A, Majo-Carbajo Y, Núñez-Palomares S, Casas-Rojo JM. Impact of an Interdisciplinary Care Program on Health Outcomes in Older Patients with Multimorbidity. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248856

Chicago/Turabian StyleCubo-Romano, Pilar, Pilar García-de-la-Torre, Carolina Medina-de-Campos, Irene Casado-López, María de-Castro-García, Alejandro Estrada-Santiago, Yolanda Majo-Carbajo, Sara Núñez-Palomares, and José Manuel Casas-Rojo. 2025. "Impact of an Interdisciplinary Care Program on Health Outcomes in Older Patients with Multimorbidity" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248856

APA StyleCubo-Romano, P., García-de-la-Torre, P., Medina-de-Campos, C., Casado-López, I., de-Castro-García, M., Estrada-Santiago, A., Majo-Carbajo, Y., Núñez-Palomares, S., & Casas-Rojo, J. M. (2025). Impact of an Interdisciplinary Care Program on Health Outcomes in Older Patients with Multimorbidity. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8856. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248856