Prediction of Periodontal Disease Progression During Supportive Periodontal Therapy Using an Oral Fluid Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity-Based Test Strip

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

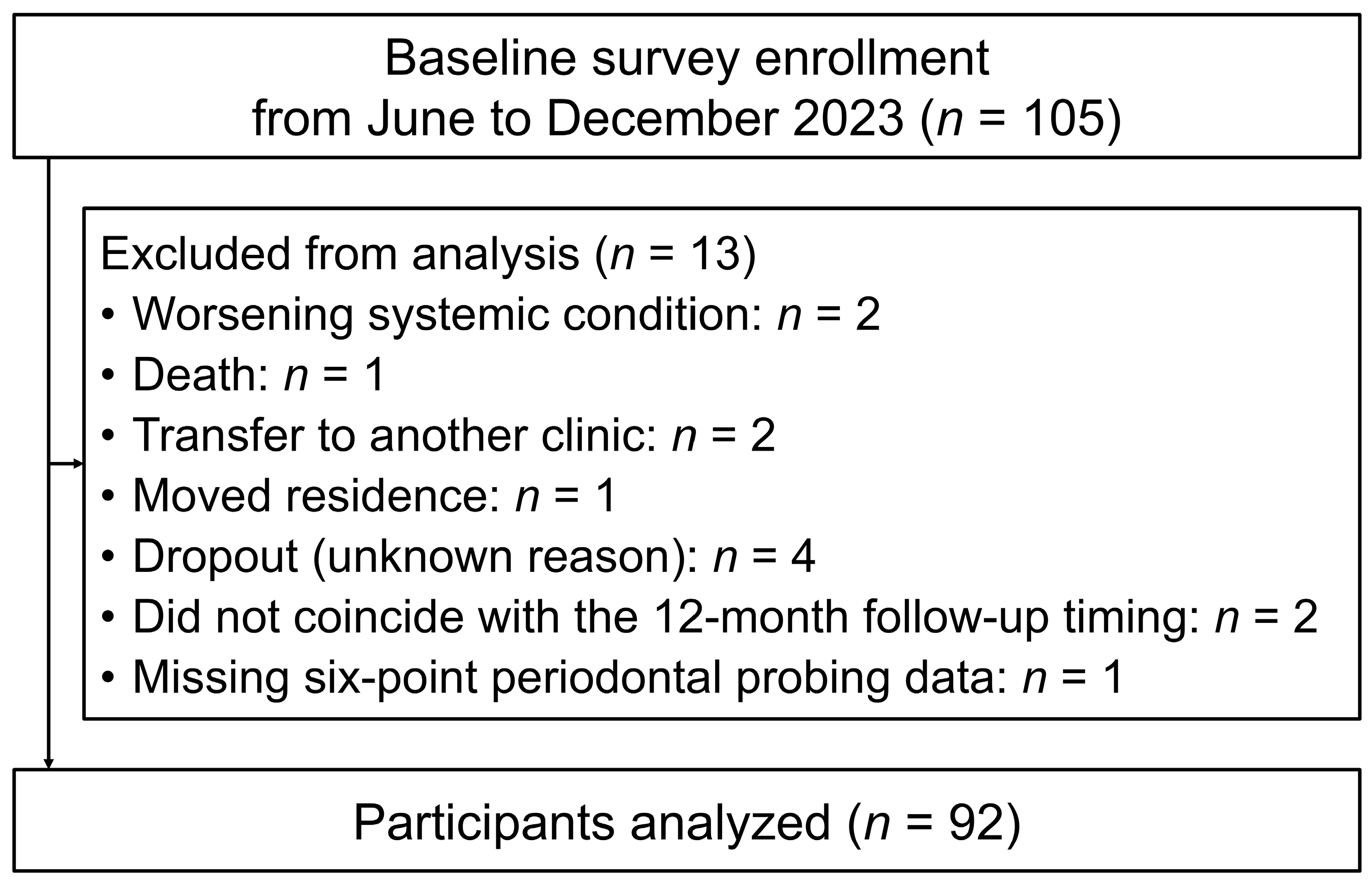

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Data Collection Using Medical Records and Questionnaires

2.3. Measurement of LD Activity in Oral Fluid

2.4. Oral Examination

2.5. Calculation of PISA and PISA-Japanese Version

2.6. Ethical Issues

2.7. Statistical Analyses

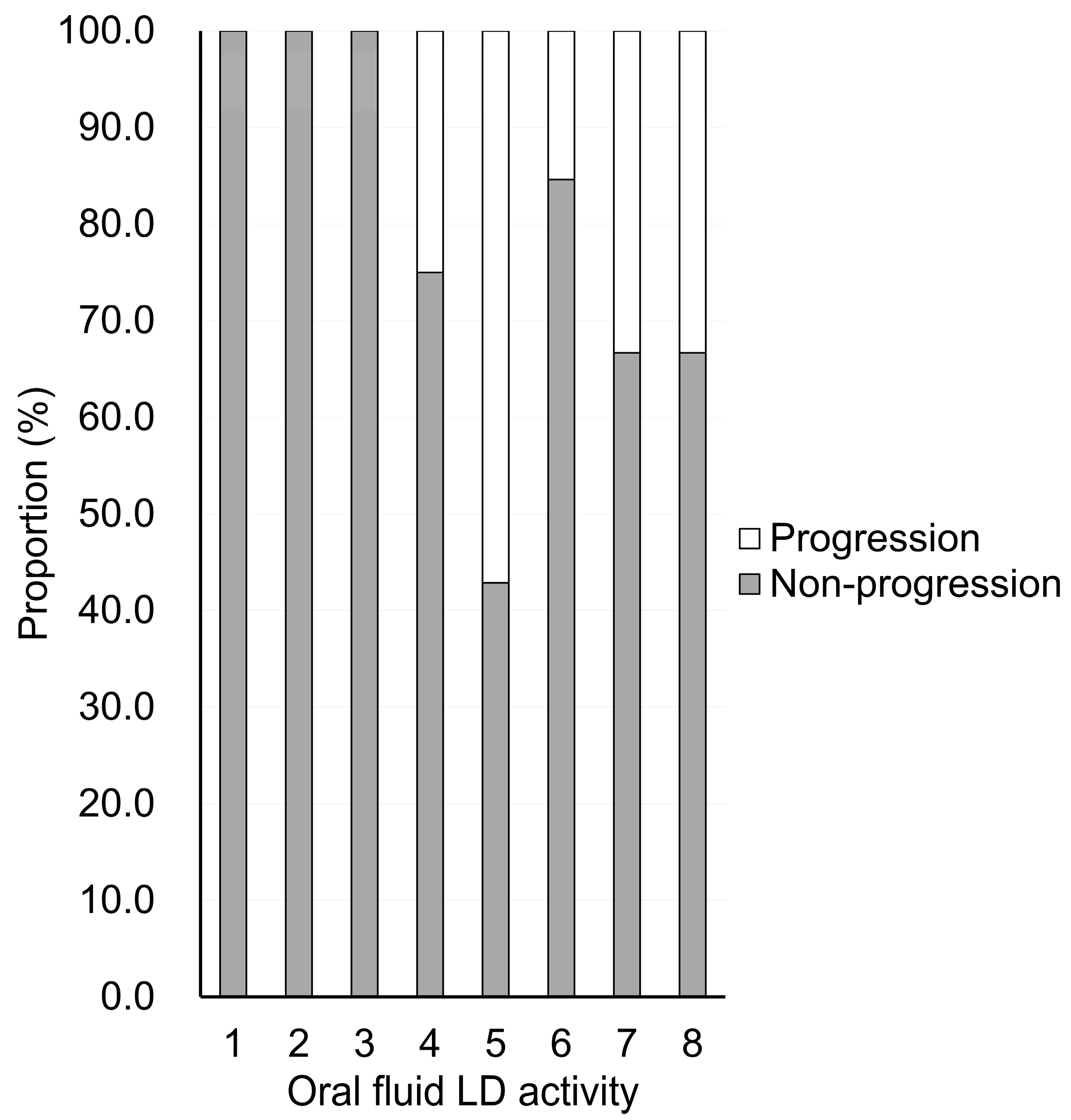

3. Results

oral fluid LD activity + 1.236 × (medication use: yes = 1, no = 0) − 4.542)))

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | area under the curve |

| BOP | bleeding on probing |

| CAL | clinical attachment level |

| LD | lactate dehydrogenase |

| NPV | negative predictive value |

| PISA | periodontal inflamed surface area |

| PPD | probing pocket depth |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| SPC | supportive periodontal care |

| SPT | supportive periodontal therapy |

References

- GBD 2021 Oral Disorders Collaborators. Trends in the global, regional, and national burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, S.Q.; Zhao, L.; Ren, Z.H.; Hu, C.Y. Global, regional, and national burden of periodontitis from 1990 to 2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihlstrom, B.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Johnson, N.W. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005, 366, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, T.C.; Clarkson, J.E.; Worthington, H.V.; MacDonald, L.; Weldon, J.C.; Needleman, I.; Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z.; Wild, S.H.; Qureshi, A.; Walker, A.; et al. Treatment of periodontitis for glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 2022, CD004714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Marco Del Castillo, A.; Jepsen, S.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; D’Aiuto, F.; Bouchard, P.; Chapple, I.; Dietrich, T.; Gotsman, I.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: Consensus report. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renvert, S.; Persson, G.R. Supportive periodontal therapy. Periodontol. 2000 2004, 36, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Herrera, D.; Kebschull, M.; Chapple, I.; Jepsen, S.; Berglundh, T.; Sculean, A.; Tonetti, M.S.; Participants, E.W.; Consultants, M. Treatment of stage I–III periodontitis—The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 4–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.; Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Mascarenhas, P.; Alcoforado, G.; Mendes, J.J.; Chambrone, L. Predictors of tooth loss during long-term periodontal maintenance: An updated systematic review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2021, 48, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.S.O.; de Freitas, M.R.; Costa, F.O.; Cortelli, S.C.; Rovai, E.S.; Cortelli, J.R. The Effects of Patient Compliance in Supportive Periodontal Therapy on Tooth Loss: A systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Int. Acad. Periodontol. 2021, 23, 17–30, Published 20210101. [Google Scholar]

- Salvi, G.E.; Roccuzzo, A.; Imber, J.C.; Stähli, A.; Klinge, B.; Lang, N.P. Clinical periodontal diagnosis. Periodontol. 2000 2023. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.P.; Joss, A.; Orsanic, T.; Gusberti, F.A.; Siegrist, B.E. Bleeding on probing. A predictor for the progression of periodontal disease? J. Clin. Periodontol. 1986, 13, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, C.G.; Mitchell, D.H.; Highfield, J.E.; Grossberg, D.E.; Stewart, D. Bacteremia due to periodontal probing: A clinical and microbiological investigation. J. Periodontol. 2001, 72, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, T. Constant force probing with and without a stent in untreated periodontal disease: The clinical reproducibility problem and possible sources of error. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1987, 14, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukwuma, D.; Arowojolu, M.; Ankita, J. A review of salivary biomarkers of periodontal disease. Ann. Ib. Postgrad. Med. 2024, 22, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nomura, Y.; Tamaki, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Arakawa, H.; Tsurumoto, A.; Kirimura, K.; Sato, T.; Hanada, N.; Kamoi, K. Screening of per-iodontitis with salivary enzyme tests. J. Oral Sci. 2006, 48, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekuni, D.; Yamane-Takeuchi, M.; Kataoka, K.; Yokoi, A.; Taniguchi-Tabata, A.; Mizuno, H.; Miyai, H.; Uchida, Y.; Fukuhara, D.; Sugiura, Y.; et al. Validity of a new kit measuring salivary lactate dehydrogenase level for screening gingivitis. Dis. Markers 2017, 2017, 9547956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi-Tabata, A.; Ekuni, D.; Azuma, T.; Yoneda, T.; Yamane-Takeuchi, M.; Kataoka, K.; Mizuno, H.; Miyai, H.; Iwasaki, Y.; Morita, M. The level of salivary lactate dehydrogenase as an indicator of the association between gingivitis and related factors in Japanese university students. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 61, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irie, K.; Sato, S.; Kamata, Y.; Mochida, Y.; Hirata, T.; Komaki, M.; Yamamoto, T. Estimation of periodontal inflamed surface area by salivary lactate dehydrogenase level using a test kit. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Irie, K.; Mochida, Y.; Hirata, T.; Azuma, T.; Iwai, K.; Yonenaga, T.; Sasai, Y.; Tomofuji, T.; Kamata, Y.; et al. Compatibility of salivary lactate dehydrogenase level using a test kit with the community periodontal index in Japanese adults. Odontology 2025, 113, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesse, W.; Abbas, F.; van der Ploeg, I.; Spijkervet, F.K.; Dijkstra, P.U.; Vissink, A. Periodontal inflamed surface area: Quantifying inflammatory burden. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, H.; Aoyama, N.; Fuchida, S.; Mochida, Y.; Minabe, M.; Yamamoto, T. Development of a Japanese version of the formula for calculating periodontal inflamed surface area: A simulation study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, K.L.; Beck, J.D.; Offenbacher, S. Clinical risk factors associated with incidence and progression of periodontal conditions in pregnant women. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, Y.; Shimada, Y.; Hanada, N.; Numabe, Y.; Kamoi, K.; Sato, T.; Gomi, K.; Arai, T.; Inagaki, K.; Fukuda, M.; et al. Salivary biomarkers for predicting the progression of chronic periodontitis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012, 57, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enevold, C.; Nielsen, C.H.; Christensen, L.B.; Kongstad, J.; Fiehn, N.E.; Hansen, P.R.; Holmstrup, P.; Havemose-Poulsen, A.; Damgaard, C. Suitability of machine learning models for prediction of clinically defined Stage III/IV periodontitis from questionnaires and demographic data in Danish cohorts. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siow, D.S.F.; Goh, E.X.J.; Ong, M.M.A.; Preshaw, P.M. Risk factors for tooth loss and progression of periodontitis in patients undergoing periodontal maintenance therapy. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, R.; Benecha, H.K.; Preisser, J.S.; Moss, K.; Starr, J.R.; Corby, P.; Genco, R.; Garcia, N.; Giannobile, W.V.; Jared, H.; et al. Modelling changes in clinical attachment loss to classify periodontal disease progression. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2016, 43, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostanci, N.; Grant, M.M.; Kebschull, M. Biological definition of periodontal diseases: A historical review of host-response diagnostics and their implications for disease classification. Periodontol. 2000 2025. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Martín, I.; Cha, J.K.; Yoon, S.W.; Sanz-Sánchez, I.; Jung, U.W. Long-term assessment of periodontal disease progression after surgical or non-surgical treatment: A systematic review. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2019, 49, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandarathodiyil, A.K.; Ramanathan, A.; Garg, R.; Doss, J.G.; Abd Rahman, F.B.; Ghani, W.M.N.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels in the Saliva of Cigarette and E-Cigarette Smokers (Vapers): A Comparative Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 3227–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangappa, S.B.; Mysore Babu, H.; R, C.S.; Jithendra, A. Diagnostic accuracy of salivary hemoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase and Interleukin-6 to determine chronic periodontitis and tooth loss in type 2 diabetics. J. Oral. Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2024, 14, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Non-Progression (n = 75) | Progression (n = 17) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 23 (30.7%) | 10 (58.8%) | 0.030 |

| Female | 52 (69.3%) | 7 (41.2%) | |

| Age (years) | 68.0 (55.0–75.0) | 69.0 (60.0–76.0) | 0.484 |

| Past smoking | |||

| No | 70 (93.3%) | 15 (88.2%) | 0.383 |

| Yes | 5 (6.7%) | 2 (11.8%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| No | 72 (96.0%) | 16 (94.1%) | 0.565 |

| Yes | 3 (4.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 60 (80.0%) | 9 (52.9%) | 0.026 |

| Yes | 15 (20.0%) | 8 (47.1%) | |

| Medication | |||

| No | 50 (66.7%) | 7 (41.2%) | 0.048 |

| Yes | 25 (33.3%) | 10 (58.8%) | |

| Oral fluid LD activity | 3 (2–5) | 5 (5–6) | <0.001 |

| Number of teeth present | 26 (21–28) | 25 (24–26) | 0.808 |

| BOP rate (%) | 2.9 (1.3–5.4) | 6.0 (4.8–9.1) | <0.001 |

| Mean PPD (mm) | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | 2.4 (2.2–2.6) | <0.001 |

| PPD ≥ 4 mm, sites | 2 (0–5) | 14 (6–20) | <0.001 |

| PPD ≥ 4 mm, rate (%) | 1.2 (0.0–3.9) | 9.3 (4.8–13.3) | <0.001 |

| PPD ≥ 6 mm, sites | 0 (0–1) | 3 (1–6) | <0.001 |

| PPD ≥ 6 mm, rate (%) | 0.0 (0.0–0.7) | 2.0 (0.6–4.1) | <0.001 |

| PISA (mm2) | 28.6 (17.1–65.3) | 113.5 (49.9–176.2) | <0.001 |

| PISA-Japanese (mm2) | 37.4 (21.6–86.2) | 132.5 (70.6–171.0) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Non-Progression (n = 75) | Progression (n = 17) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of teeth present | 26 (21–28) | 25 (24–25) | 0.442 |

| BOP rate (%) | 1.8 (0.0–5.8) | 5.6 (4.7–10.1) | 0.002 |

| Mean PPD (mm) | 2.1 (1.8–2.3) | 2.6 (2.2–2.8) | <0.001 |

| PPD ≥ 4 mm, sites | 1 (0–4.5) | 17 (10–20) | <0.001 |

| PPD ≥ 4 mm, rate (%) | 0.9 (0.0–3.1) | 10.7 (7.9–14.7) | <0.001 |

| PPD ≥ 6 mm, sites | 0 (0–1) | 5 (4–9) | <0.001 |

| PPD ≥ 6 mm, rate (%) | 0.0 (0.0–0.6) | 3.3 (2.6–6.0) | <0.001 |

| PISA (mm2) | 18.1 (0.0–71.8) | 125.7 (81.5–164.5) | <0.001 |

| PISA-Japanese (mm2) | 31.0 (0.0–92.8) | 129.3 (89.4–177.7) | <0.001 |

| Number of sites with progression | 0 (0–1) | 6 (5–7) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Cutoff Point | Area Under the Curve | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | Likelihood Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral fluid LD activity | 3.5 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 2.14 |

| BOP rate (%) | 3.3 | 0.78 | 1.00 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 1.00 | 2.27 |

| Mean PPD (mm) | 2.4 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.46 | 0.91 | 3.74 |

| PPD ≥ 4 mm, sites | 5.5 | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.94 | 3.37 |

| PPD ≥ 4 mm, rate (%) | 4.7 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.46 | 0.94 | 3.83 |

| PPD ≥ 6 mm, sites | 1.5 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 0.91 | 4.04 |

| PPD ≥ 6 mm, rate (%) | 1.5 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 0.91 | 4.04 |

| PISA (mm2) | 44.5 | 0.82 | 0.94 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 2.52 |

| PISA-Japanese (mm2) | 111.1 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 0.50 | 0.91 | 4.40 |

| Independent Variables | Coefficients | Standard Error | Wald Value | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Oral fluid LD activity | 0.548 | 0.182 | 9.018 | 1.730 | 1.21 | 2.473 | 0.003 |

| Medication (yes: 1, no: 0) | 1.236 | 0.605 | 4.181 | 3.443 | 1.053 | 11.261 | 0.041 |

| Constant | −4.542 | 1.063 | 18.266 | 0.011 | - | - | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamamoto, T.; Sato, S.; Kamata, Y.; Hirata, T.; Nanashima, K.; Irie, K.; Komaki, M. Prediction of Periodontal Disease Progression During Supportive Periodontal Therapy Using an Oral Fluid Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity-Based Test Strip. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8810. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248810

Yamamoto T, Sato S, Kamata Y, Hirata T, Nanashima K, Irie K, Komaki M. Prediction of Periodontal Disease Progression During Supportive Periodontal Therapy Using an Oral Fluid Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity-Based Test Strip. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8810. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248810

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamamoto, Tatsuo, Satsuki Sato, Yohei Kamata, Takahisa Hirata, Keiichiro Nanashima, Koichiro Irie, and Motohiro Komaki. 2025. "Prediction of Periodontal Disease Progression During Supportive Periodontal Therapy Using an Oral Fluid Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity-Based Test Strip" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8810. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248810

APA StyleYamamoto, T., Sato, S., Kamata, Y., Hirata, T., Nanashima, K., Irie, K., & Komaki, M. (2025). Prediction of Periodontal Disease Progression During Supportive Periodontal Therapy Using an Oral Fluid Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity-Based Test Strip. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8810. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248810