Chronic Pruritus Severity and Its Association with Clinical Frailty in Geriatric Dermatology Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

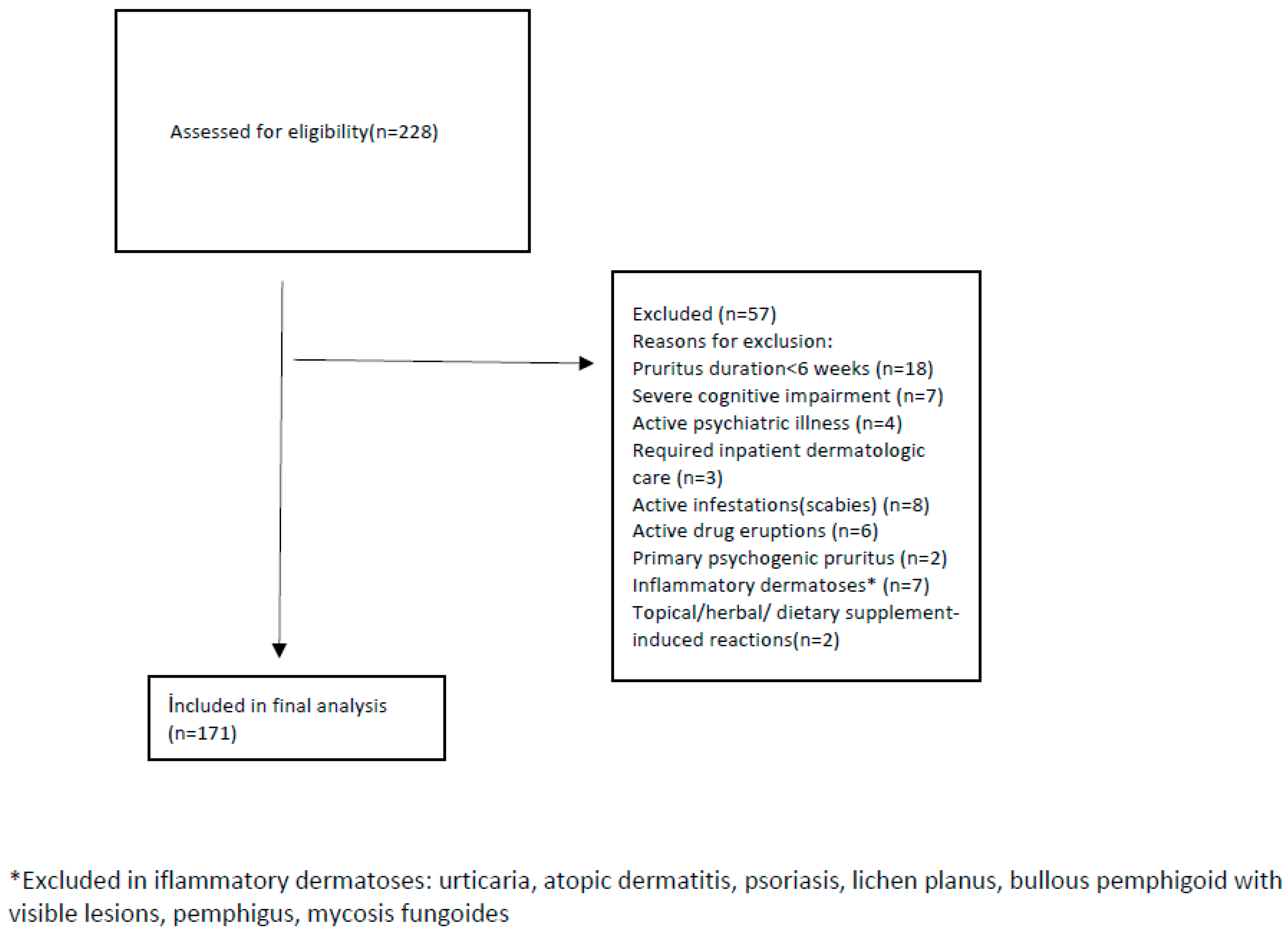

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Pruritus and Frailty Assessments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, T.; Tey, H.L.; Yosipovitch, G. Chronic Pruritus in the Geriatric Population. Dermatol. Clin. 2018, 3, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, M.; Kobus, C.; Perner, C.; Schönenberg, A.; Prell, T. Chronic Pruritus in Geriatric Patients: Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Itch-related Quality of Life. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2025, 105, adv42003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, F.; Xiong, Y. Prevalence and risk factors of senile pruritus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes-Rodriguez, R.; Mollanazar, N.K.; González-Muro, J.; Nattkemper, L.; Torres-Alvarez, B.; López-Esqueda, F.J.; Chan, Y.H.; Yosipovitch, G. Itch prevalence and characteristics in a Hispanic geriatric population: A comprehensive study using a standardized itch questionnaire. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2015, 95, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçin, B.; Tamer, E.; Toy, G.G.; Oztaş, P.; Hayran, M.; Alli, N. The prevalence of skin diseases in the elderly: Analysis of 4099 geriatric patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 2006, 45, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.H.; Chen, K.H.; Tseng, M.P.; Sun, C.C. Pattern of skin diseases in a geriatric patient group in Taiwan: A 7-year survey from the outpatient clinic of a university medical center. Dermatology 2001, 203, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reszke, R.; Białynicki-Birula, R.; Lindner, K.; Sobieszczańska, M.; Szepietowski, J.C. Itch in Elderly People: A Cross-sectional Study. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2019, 99, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, T.G.; Steinhoff, M. Pruritus in elderly patients-eruptions of senescence. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2011, 30, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, A.; Valdes-Rodriguez, R.; Yosipovitch, G. Causes, pathophysiology, and treatment of pruritus in the mature patient. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 36, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerc, C.J.; Misery, L. A Literature Review of Senile Pruritus: From Diagnosis to Treatment. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2017, 97, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourzali, K.M.; Yosipovitch, G. Management of Itch in the Elderly: A Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 9, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhoff, M.; Al-Khawaga, S.; Buddenkotte, J. Itch in elderly patients: Origin, diagnostics, management. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 152, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.Y.; Um, J.Y.; Kim, J.C.; Kang, S.Y.; Park, C.W.; Kim, H.O. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Pruritus in Elderly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Liu, G.; Gao, H.; Wu, Q.; Meng, J.; Wang, F.; Jiang, S.; Chen, M.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Geriatric syndromes, chronic inflammation, and advances in the management of frailty: A review with new insights. Biosci. Trends 2023, 17, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Valencia, M.; Izquierdo, M.; Cesari, M.; Casas-Herrero, Á.; Inzitari, M.; Martínez-Velilla, N. The relationship between frailty and polypharmacy in older people: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1432–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ersoy Altınok, N.; Akyar, İ. Validity and reliability of 5-D itch scale on chronic renal disease patients. ACU Sağlık Bil. Derg. 2018, 9, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.S.; Kwan, Z.; Ch’ng, C.C.; Yong, A.S.W.; Tan, L.L.; Han, W.H.; Kamaruzzaman, S.B.; Chin, A.V.; Tan, M.P. Self-reported generalised pruritus among community-dwelling older adults in Malaysia. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazan, P.; Lesiak, A.; Skibińska, M.; Rynkowska-Kidawa, M.; Bednarski, I.; Sobolewska-Sztychny, D.; Noweta, M.; Narbutt, J. Pruritus prevalence and characteristics in care and treatment facility and geriatric outpatient clinic patients: A cross-sectional study using a standardized pruritus questionnaires. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2024, 41, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, M.; Calvani, R.; Marzetti, E. Frailty in Older Persons. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 33, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zeng, X.; He, F.; Huang, X. Inflammatory biomarkers of frailty: A review. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 179, 112253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorge, N.E.; Scheerders, E.R.; Dudink, K.; Oudshoorn, C.; Polinder-Bos, H.A.; Waalboer-Spuij, R.; Schlejen, P.M.; van Montfrans, C. A prospective, multicentre study to assess frailty in elderly patients with leg ulcers (GERAS study). J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umegaki, H. Frailty, multimorbidity, and polypharmacy: Proposal of the new concept of the geriatric triangle. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2025, 25, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogame, T.; Kamitani, T.; Yamazaki, H.; Ogawa, Y.; Fukuhara, S.; Kabashima, K.; Yamamoto, Y. Longitudinal association between polypharmacy and development of pruritus: A Nationwide Cohort Study in a Japanese Population. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 2059–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokuzlar, O.; Soysal, P.; Isik, A.T. Association between serum vitamin B12 level and frailty in older adults. North. Clin. Istanb. 2017, 4, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miniksar, O.H.; Honca, T.; Parlak Cikrikci, A.; Gocmen, A.Y. Frailty index is associated with vitamin D insufficiency in geriatric surgery patients: A Prospective Observational Study. J. Anesthesiol. Reanim. Spec. Soc. 2023, 31, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) | Mean ± SD/Median [IQR] |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, years | 73.1 ± 6.5, 71.0 [68.0–77.5] | |

| Female | 95 (55.6) | |

| Male | 76 (44.4) | |

| Education level | ||

| Primary school or below | 21 (12.3) | |

| Middle school | 67 (39.2) | |

| High school | 69 (40.4) | |

| University or above | 14 (8.2) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 113 (66.1) | |

| Single | 8 (4.7) | |

| Divorced | 12 (7.0) | |

| Widowed | 38 (22.2) | |

| Living situation | ||

| With family | 130 (76.0) | |

| Alone | 27 (15.8) | |

| Nursing home/institutionalized | 14 (8.2) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Itch duration, months | 12.5 ± 7.9, 10.0 [7.0–15.5] | |

| Number of drugs | 4.4 ± 1.5, 4.0 [3.0–5.0] | |

| Polypharmacy (≥5 drugs), yes | 83 (48.5) | |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.3 ± 1.0, 1.0 [1.0–2.0] | |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension, yes | 68 (40.5) | |

| Diabetes, yes | 42 (25.0) | |

| Cardiovascular disease, yes | 28 (16.7) | |

| Renal disease, yes | 15 (8.9) | |

| Thyroid disease, yes | 12 (7.1) | |

| Anemia, yes | 20 (11.9) | |

| Malignancy, yes | 10 (6.0) | |

| Pruritus severity | ||

| VAS (0–10) | 6.2 ± 2.6, 6.0 [4.0–8.5] | |

| 5-D Itch total (5–25) | 12.5 ± 3.1, 12.0 [10.0–15.0] | |

| Xerosis (ODS) | ||

| None | 73 (42.7) | |

| Mild | 59 (34.5) | |

| Moderate | 38 (22.2) | |

| Severe | 1 (0.6) | |

| FRAIL categories | ||

| Non-frail (0) | 27 (15.8) | |

| Pre-frail (1–2) | 69 (40.4) | |

| Frail (3–5) | 75 (43.9) |

| Variable | Non-Frail (n = 27) | Pre-Frail (n = 69) | Frail (n = 75) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

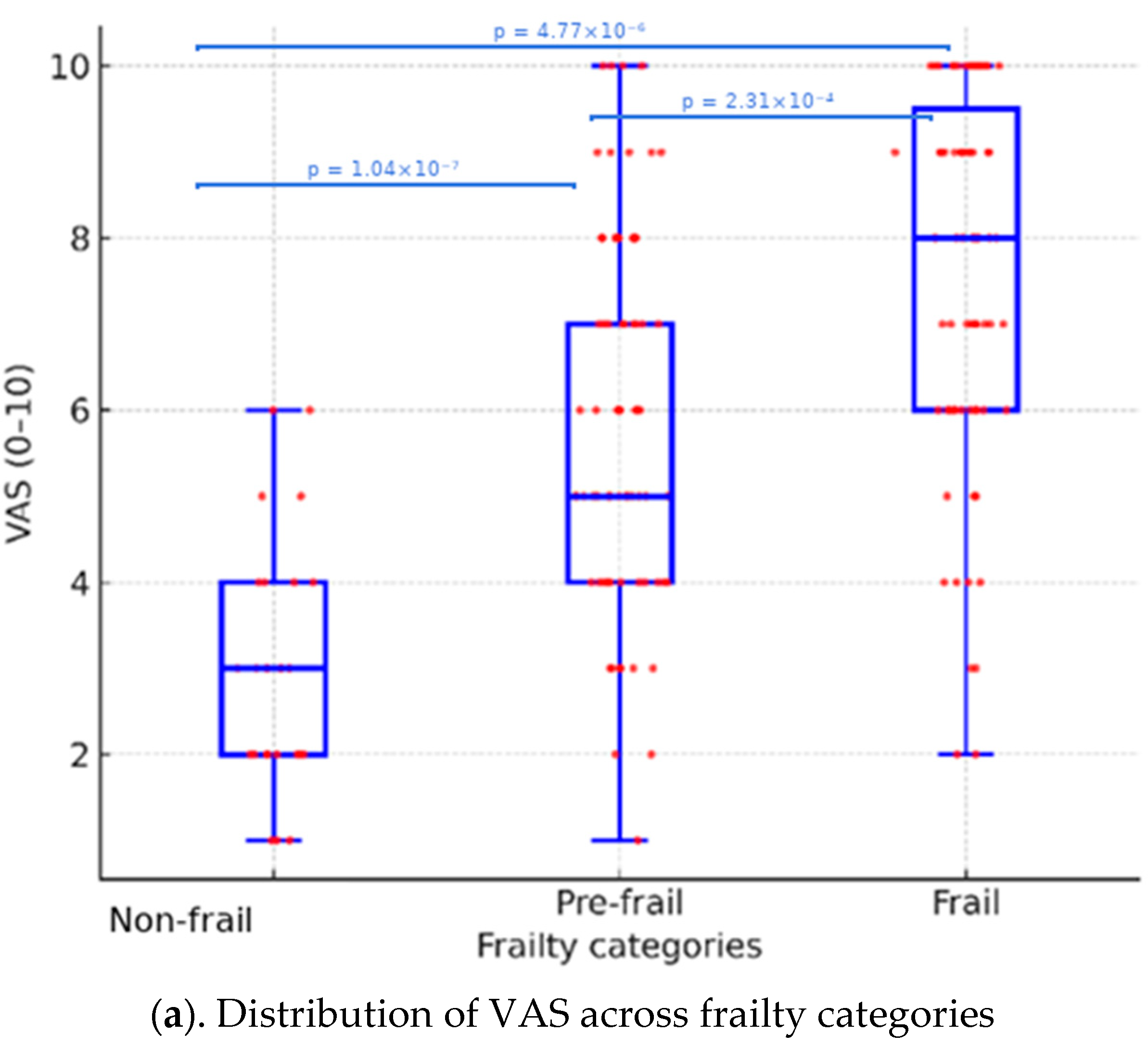

| VAS (0–10) | 3.0 ± 1.4, 3.0 [2.0–4.0] | 5.8 ± 2.2, 5.0 [4.0–7.0] | 7.7 ± 2.2, 8.0 [6.0–9.5] | <0.001 * |

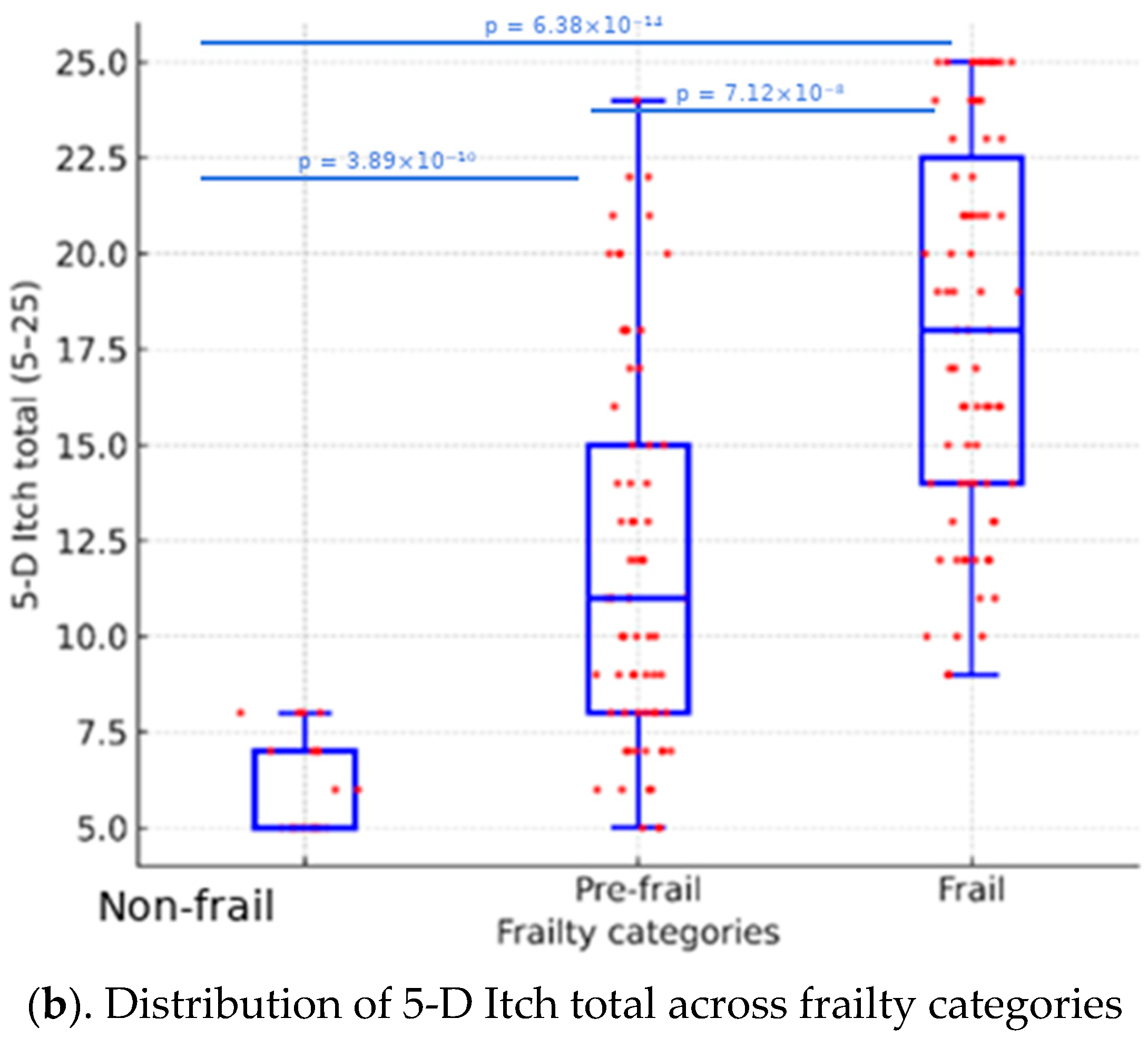

| 5-D Itch total score (5–25) | 5.8 ± 1.2, 5.0 [5.0–7.0] | 11.9 ± 5.0, 11.0 [8.0–15.0] | 18.0 ± 5.0, 18.0 [14.0–22.5] | <0.001 * |

| Itch duration, months | 8.2 ± 4.3, 7.0 [5.5–9.0] | 12.2 ± 6.9, 10.0 [8.0–16.0] | 14.3 ± 9.1, 11.0 [8.0–18.5] | 0.001 * |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.0 ± 0.9, 1.0 [0.0–2.0] | 1.6 ± 1.0, 1.0 [1.0–2.0] | 1.2 ± 1.0, 1.0 [0.5–2.0] | 0.038 * |

| Polypharmacy, yes | 4 (14.8%) | 30 (43.5%) | 49 (65.3%) | <0.001 * |

| Xerosis (ODS ≥ 2), yes | 3 (11.1%) | 17 (24.6%) | 19 (25.3%) | 0.041 * |

| Variable | No Polypharmacy (n = 88) | Polypharmacy (n = 83) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAS (0–10) | 4.8 ± 2.2, 5.0 [3.0–6.0] | 7.7 ± 2.1, 8.0 [6.0–9.5] | <0.001 * |

| 5-D Itch total (5–25) | 10.3 ± 4.9, 9.0 [6.8–13.0] | 17.2 ± 5.7, 18.0 [13.0–21.5] | <0.001 * |

| Itch duration, months | 9.0 ± 5.6, 8.0 [6.0–10.0] | 16.3 ± 8.3, 13.0 [10.0–22.0] | <0.001 * |

| Number of comorbidities | 0.9 ± 0.8, 1.0 [0.0–1.2] | 1.8 ± 1.0, 2.0 [1.0–3.0] | <0.001 * |

| Xerosis (ODS ≥ 2), yes | 11 (12.5%) | 28 (33.7%) | 0.002 * |

| Frailty categories | <0.001 * | ||

| Non-frail | 22 (25.0%) | 5 (6.0%) | |

| Pre-frail | 41 (46.6%) | 28 (33.7%) | |

| Frail | 25 (28.4%) | 50 (60.2%) |

| Variable | 0 Comorbidities (n = 37) | 1 Comorbidity (n = 66) | ≥2 Comorbidities (n = 68) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS (0–10) | 5.0 [3.0–7.0] | 6.0 [5.0–9.0] | 6.0 [4.0–9.0] | 0.063 |

| 5-D Itch total (5–25) | 10.0 [8.0–15.0] | 14.0 [8.5–20.0] | 12.0 [8.0–20.0] | 0.097 |

| Variable | ODS 0—None (n = 73) | ODS 1—Mild (n = 59) | ODS 2—Moderate (n = 38) | ODS 3—Severe (n = 1) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS (0–10) | 5.0 [3.0–7.0] | 6.0 [4.0–8.0] | 7.0 [5.0–9.0] | 9.0 [9.0–9.0] | <0.001 * |

| 5-D Duration | 2.0 [1.0–3.0] | 3.0 [2.0–4.0] | 3.0 [2.0–4.0] | 4.0 [4.0–4.0] | <0.001 * |

| 5-D Intensity | 2.0 [1.0–3.0] | 3.0 [2.0–4.0] | 4.0 [3.0–5.0] | 4.0 [4.0–4.0] | <0.001 * |

| 5-D Direction | 1.0 [1.0–2.0] | 2.0 [1.0–2.0] | 2.0 [2.0–3.0] | 3.0 [3.0–3.0] | 0.014 * |

| 5-D Disability | 2.0 [1.0–3.0] | 3.0 [2.0–4.0] | 3.0 [2.0–4.0] | 4.0 [4.0–4.0] | <0.001 * |

| 5-D Distribution | 2.0 [1.0–3.0] | 3.0 [2.0–4.0] | 3.0 [2.0–4.0] | 4.0 [4.0–4.0] | <0.001 * |

| Variable | VAS (r, p) | 5-D Itch Total (r, p) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.035 (p = 0.646) | 0.052 (p = 0.503) |

| Itch duration (months) | 0.786 (p < 0.001) | 0.610 (p < 0.001) |

| Number of comorbidities | 0.188 (p = 0.014 *) | 0.111 (p = 0.148) |

| Number of medications | 0.555 (p < 0.001) | 0.538 (p < 0.001) |

| Xerosis (ODS score) | 0.660 (p < 0.001) | 0.538 (p < 0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurmuş, G.I.; Menteşoğlu, D.; Çöteli, S.; Kartal, S.P. Chronic Pruritus Severity and Its Association with Clinical Frailty in Geriatric Dermatology Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8809. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248809

Kurmuş GI, Menteşoğlu D, Çöteli S, Kartal SP. Chronic Pruritus Severity and Its Association with Clinical Frailty in Geriatric Dermatology Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8809. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248809

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurmuş, Gökçe Işıl, Dilek Menteşoğlu, Süheyla Çöteli, and Selda Pelin Kartal. 2025. "Chronic Pruritus Severity and Its Association with Clinical Frailty in Geriatric Dermatology Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8809. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248809

APA StyleKurmuş, G. I., Menteşoğlu, D., Çöteli, S., & Kartal, S. P. (2025). Chronic Pruritus Severity and Its Association with Clinical Frailty in Geriatric Dermatology Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8809. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248809