The VIRTUE Index: A Novel Echocardiographic Marker Integrating Right–Left Ventricular Hemodynamics in Acute Heart Failure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

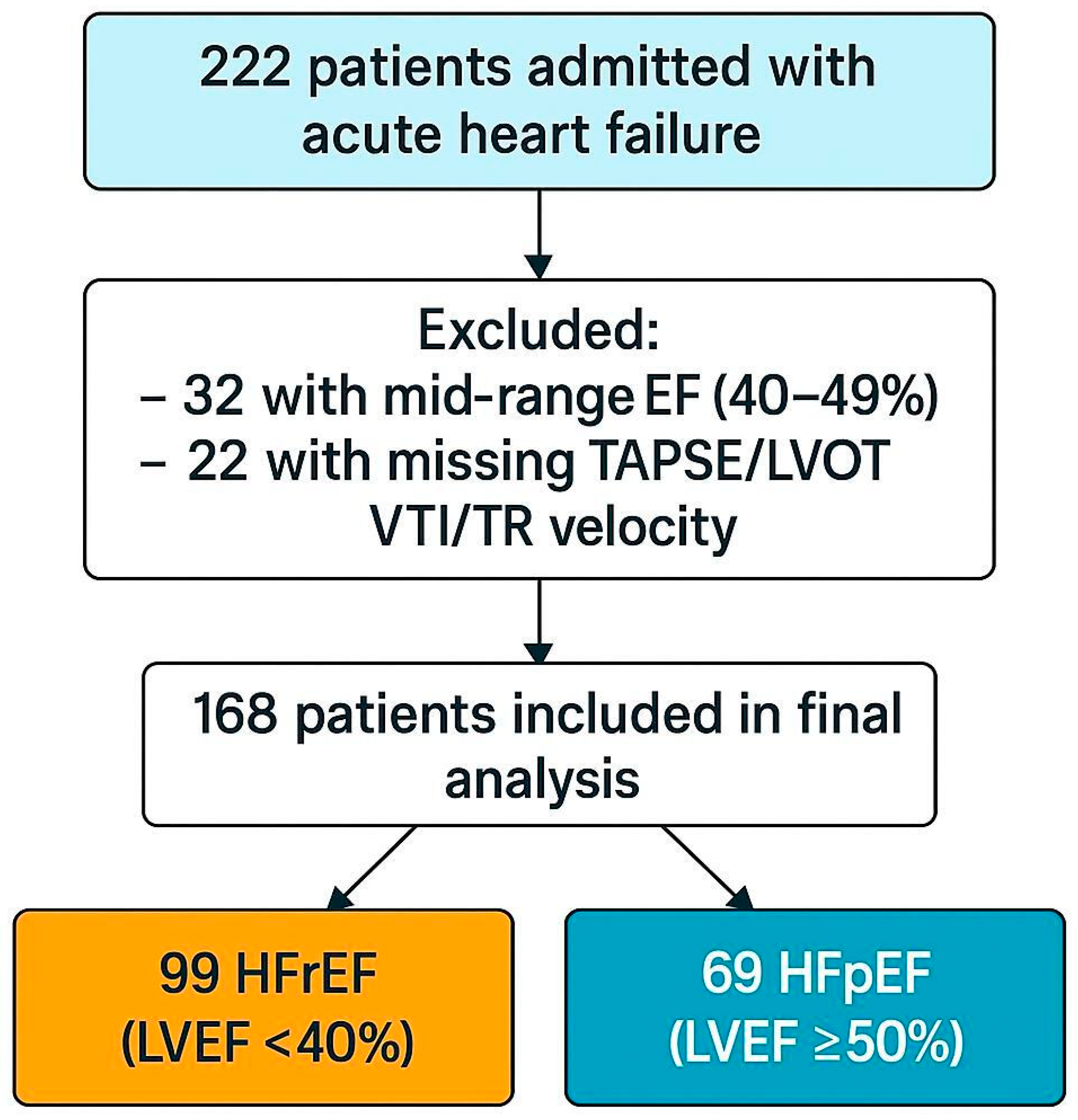

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Echocardiographic Assessment

2.3. Biomarker Measurement

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

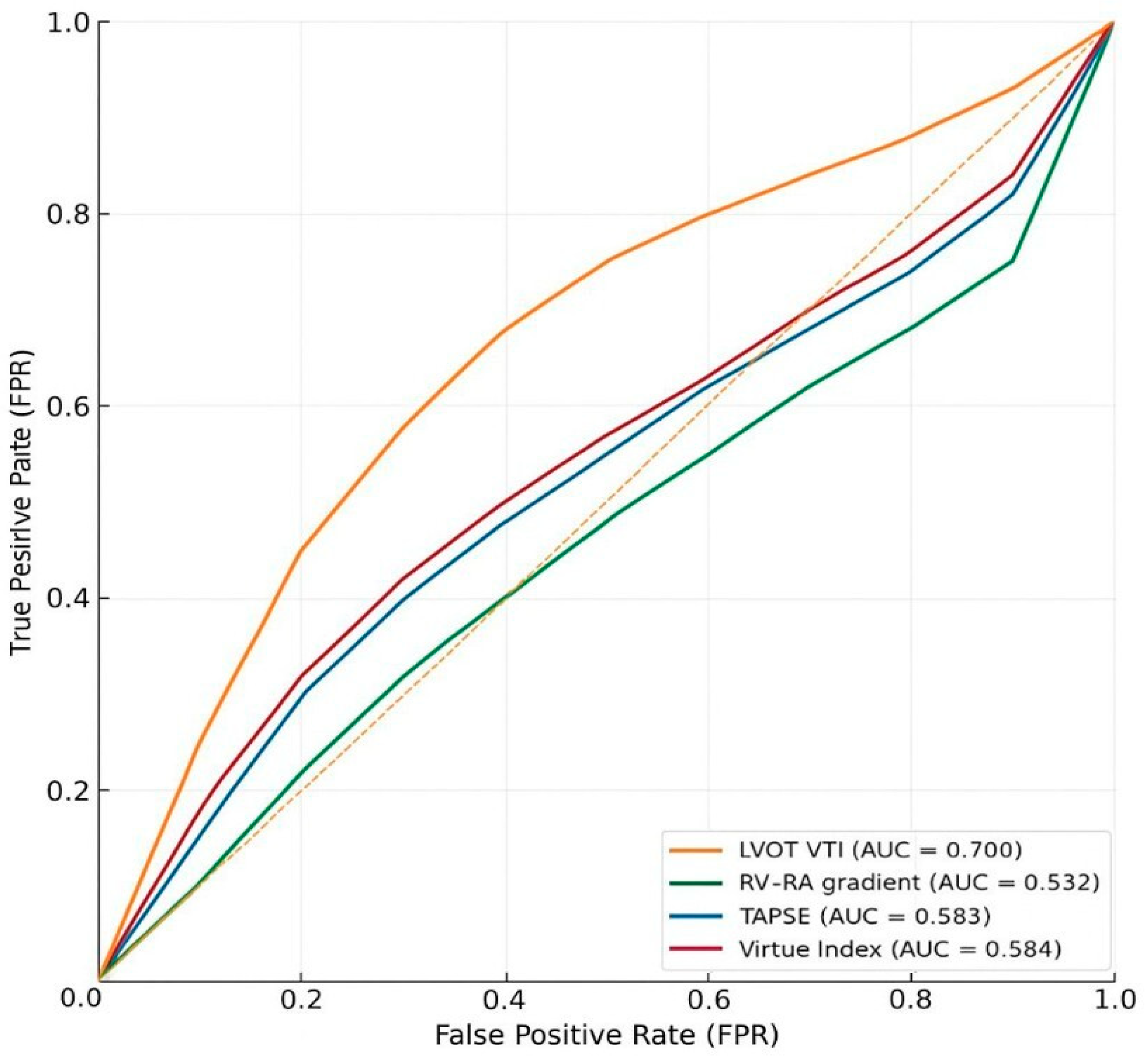

3.2. Prognostic Discrimination for In-Hospital Mortality (ROC/AUC Analyses)

Interpretation

3.3. Correlation Between Virtue Index and NT-proBNP

3.4. Pairwise AUC Comparisons Between Virtue and Conventional Parameters

Interpretation

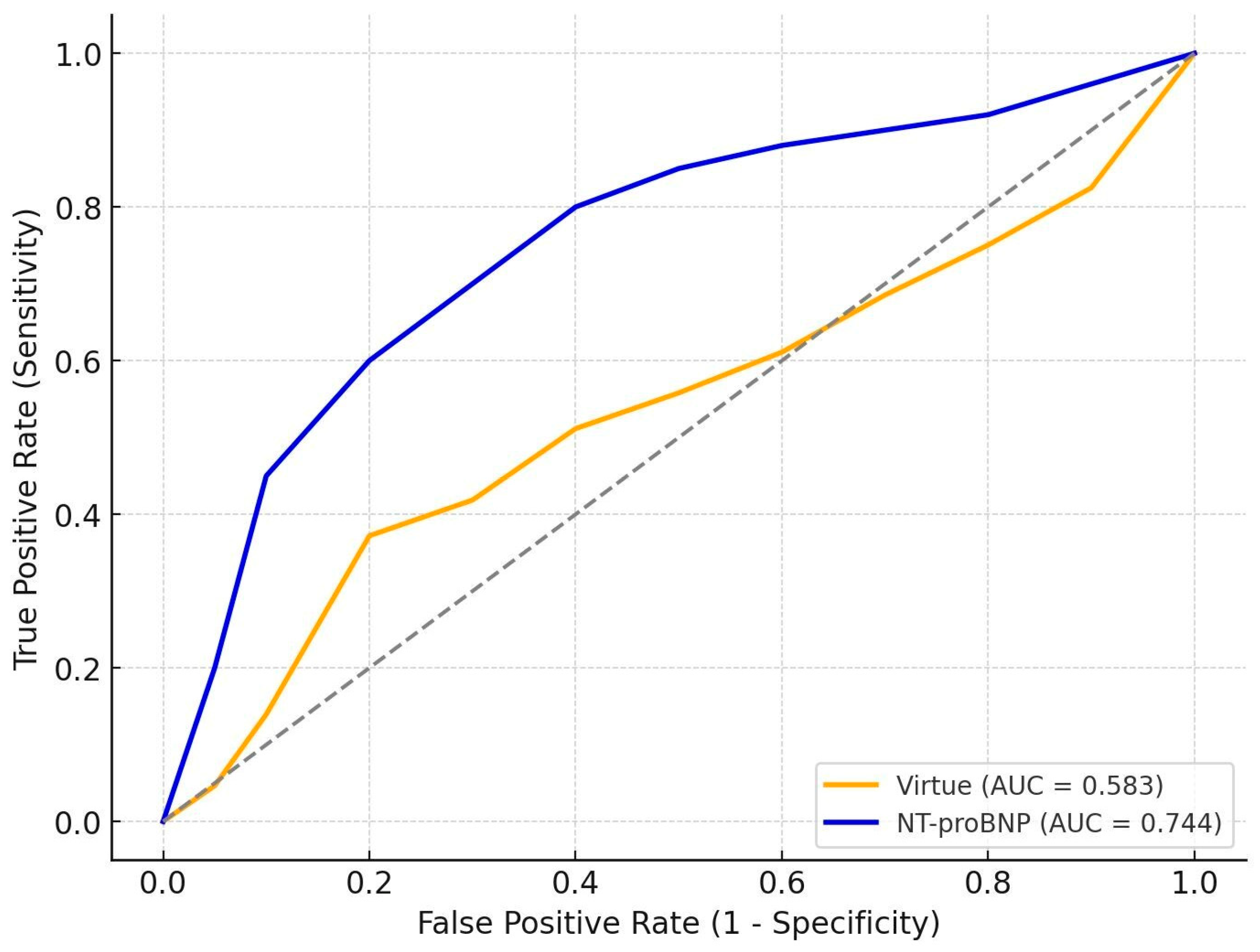

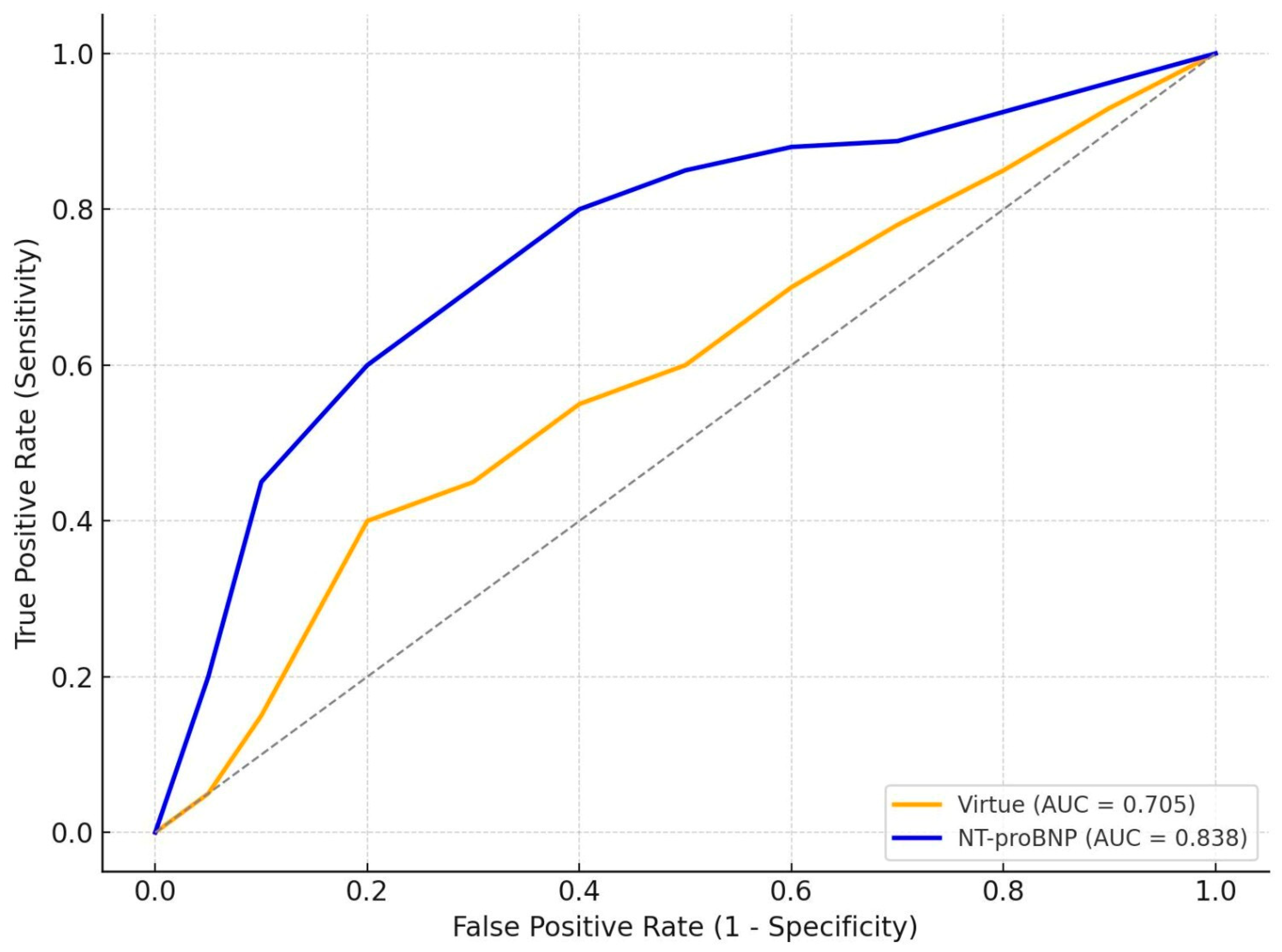

3.5. Comparative Prognostic Performance of Virtue and NT-proBNP

Interpretation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| AHF | Acute Heart Failure |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| EF | Ejection Fraction |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| HFpEF | Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LV | Left Ventricle |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| LVOT VTI | Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Velocity Time Integral |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| RV | Right Ventricle |

| RV–RA gradient | Right Ventricular to Right Atrial Pressure Gradient |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TAPSE | Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion |

References

- Ambrosy, A.P.; Fonarow, G.C.; Butler, J.; Chioncel, O.; Greene, S.J.; Vaduganathan, M.; Nodari, S.; Lam, C.S.; Sato, N.; Shah, A.N.; et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: Lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioncel, O.; Mebazaa, A.; Harjola, V.; Coats, A.J.; Piepoli, M.F.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Laroche, C.; Seferovic, P.M.; Anker, S.D.; Ferrari, R.; et al. Clinical phenotypes and outcome of patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: The ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1242–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.K.; Powers, J.C.; Nomeir, A.M.; Fowle, K.; Kitzman, D.W.; Rankin, K.M.; Little, W.C. The pathogenesis of acute pulmonary edema associated with hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiade, M.; De Luca, L.; Fonarow, G.C.; Filippatos, G.; Metra, M.; Francis, G.S. Pathophysiologic targets in the early phase of acute heart failure syndromes. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 11G–17G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.-P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2129–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.J.; Katz, D.H.; Deo, R.C. Phenotypic spectrum of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail. Clin. 2014, 10, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passantino, A.; Scrutinio, D. Risk stratification in acute heart failure: We need a new agenda for clinical research. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 293, 179–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, P.A.; Nowak, R.M.; McCord, J.; Hollander, J.E.; Herrmann, H.C.; Steg, P.G.; Duc, P.; Westheim, A.; Omland, T.; Knudsen, C.W.; et al. B-type natriuretic peptide and clinical judgment in emergency diagnosis of heart failure: Analysis from the Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study. Circulation 2002, 106, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisel, A.S.; Krishnaswamy, P.; Nowak, R.M.; McCord, J.; Hollander, J.E.; Duc, P.; Omland, T.; Storrow, A.B.; Abraham, W.T.; Wu, A.H.; et al. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Januzzi, J.L., Jr.; Camargo, C.A.; Anwaruddin, S.; Baggish, A.L.; Chen, A.A.; Krauser, D.G.; Tung, R.; Cameron, R.; Nagurney, J.T.; Chae, C.U.; et al. The N-terminal Pro-BNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 95, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudski, L.G.; Lai, W.W.; Afilalo, J.; Hua, L.; Handschumacher, M.D.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Solomon, S.D.; Louie, E.K.; Schiller, N.B. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 685–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obokata, M.; Reddy, Y.N.V.; Borlaug, B.A. The role of echocardiography in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: What do we want from imaging? Heart Fail. Clin. 2019, 15, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, F.L.; Barletta, V.; Ballo, P.; Cioffi, G.; Pugliese, N.R.; Rossi, A.; Bajraktari, G.; Ghio, S.; Henein, M.Y. Left ventricular outflow indices in chronic systolic heart failure: Thresholds and prognostic value. Echocardiography 2025, 42, e70109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omote, K.; Nagai, T.; Iwano, H.; Tsujinaga, S.; Kamiya, K.; Aikawa, T.; Konishi, T.; Sato, T.; Kato, Y.; Komoriyama, H.; et al. Left ventricular outflow tract velocity time integral in hospitalized heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F.; Doyle, R.; Murphy, D.J.; Hunt, S.A. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, part II: Pathophysiology, clinical importance, and management of right ventricular failure. Circulation 2008, 117, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guazzi, M.; Naeije, R.; Arena, R.; Corrà, U.; Ghio, S.; Forfia, P.; Rossi, A.; Cahalin, L.P.; Bandera, F.; Temporelli, P. Echocardiography of right ventriculoarterial coupling combined with cardiopulmonary exercise testing to predict outcome in heart failure. Chest 2015, 148, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grapsa, J.; Dawson, D.; Nihoyannopoulos, P. Assessment of right ventricular structure and function in pulmonary hypertension. J. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2011, 19, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, V.C.; Takeuchi, M. Echocardiographic assessment of right ventricular systolic function. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2018, 8, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, M.I.; Kanwar, M.K.; Lander, M.M.; Hamid, N.B.; Raina, A.; Sethi, S.S.; Finn, M.T.; Fried, J.A.; Raikhelkar, J.; Masoumi, A.; et al. Impact of interventricular interaction on ventricular function: Insights from right ventricular pressure–volume analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2024, 12, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.C.; Ciobanu, M.; Țînț, D.; Nechita, A.C. Linking heart function to prognosis: The role of a novel echocardiographic index and NT-proBNP in acute heart failure. Medicina 2025, 61, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 233–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F., 3rd; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 277–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badano, L.P.; Addetia, K.; Pontone, G.; Torlasco, C.; Lang, R.M.; Parati, G.; Muraru, D. Advanced imaging of right ventricular anatomy and function. Heart 2020, 106, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, K.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Ghosh, S.; Chowdhury, S. Natriuretic peptides: Diagnostic and therapeutic use. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 15, S345–S353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, H.; Albert, N.M.; Coats, A.J.S.; Anker, S.D.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Butler, J.; Chioncel, O.; Defilippi, C.R.; Drazner, M.H.; Felker, G.M.; et al. Natriuretic peptides: Role in the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettersten, N. Biomarkers in acute heart failure: Diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Int. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 3, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K. T test as a parametric statistic. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2015, 68, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachar, N. The Mann–Whitney U: A test for assessing whether two independent samples come from the same distribution. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2008, 4, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.H. Handbook of Biological Statistics, 3rd ed.; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzuoli, A.; Cartocci, A.; Pirrotta, F.; Vannuccini, F.; Campora, A.; Martini, L.; Dini, F.L.; Carluccio, E.; Ruocco, G. Different right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary coupling in acute heart failure according to left ventricular ejection fraction. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 81, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttin, O.; Fraser, A.G.; Lund, L.H.; Donal, E.; Linde, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Erdei, T.; Machu, J.; Duarte, K.; Rossignol, P.; et al. Risk stratification with echocardiographic biomarkers in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The MEDIA Echo Score. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 1827–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melenovsky, V.; Hwang, S.J.; Lin, G.; Redfield, M.M.; Borlaug, B.A. Right heart dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 3452–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschöpe, C.; Birner, C.; Böhm, M.; Bruder, O.; Frantz, S.; Luchner, A.; Maier, L.; Störk, S.; Kherad, B.; Laufs, U. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Current management and future strategies. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2018, 107, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, J.; Luo, Z.; Tan, X.; Ren, R.; Fujita, T.; Kashima, Y.; Tanimura, T.L.; Wang, M.; et al. Right ventricular–pulmonary arterial coupling and outcome in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Clin. Cardiol. 2024, 47, e24308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabima, D.M.; Philip, J.L.; Chesler, N.C. Right ventricular–pulmonary vascular interactions. Physiology 2017, 32, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.; de la Espriella, R.; Rossignol, P.; Voors, A.A.; Mullens, W.; Metra, M.; Chioncel, O.; Januzzi, J.L.; Mueller, C.; Richards, A.M.; et al. Congestion in heart failure: A circulating biomarker-based perspective. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 1751–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guazzi, M.; Villani, S.; Generati, G.; Ferraro, O.E.; Pellegrino, M.; Alfonzetti, E.; Labate, V.; Gaeta, M.; Sugimoto, T.; Bandera, F. Right ventricular contractile reserve and pulmonary circulation uncoupling during exercise challenge in heart failure: Pathophysiology and clinical phenotypes. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troughton, R.W.; Richards, A.M. B-type natriuretic peptides and echocardiographic measures of cardiac structure and function. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2009, 2, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n = 168) | HFrEF (n = 99) | HFpEF (n = 69) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71 ± 14 | 65.9 ± 14.9 | 77.6 ± 9.6 | <0.001 |

| Male sex, % | 50.6% | 66.7% | 27.5% | <0.001 |

| Smoking, % | 25.5% | 36.4% | 8.7% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 88.1% | 82.8% | 95.7% | 0.017 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 94.6% | 94.9% | 94.2% | 0.830 |

| Obesity, % | 28.1% | 30.3% | 24.6% | 0.460 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 39.9% | 41.4% | 37.7% | 0.630 |

| Valvular heart disease, % | 78.0% | 80.8% | 73.9% | 0.290 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 143 ± 31 | 143 ± 31 | 142 ± 31 | 0.837 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 85 ± 17 | 87 ± 17 | 81 ± 17 | 0.026 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 7830 (3698–21,764) | 8453 (4957–21,121) | 6537 (2180–24,554) | 0.411 |

| RV–RA gradient (mmHg) | 30.0 (22.8–40.0) | 17.0 (14.0–22.0) | 21.0 (17.0–24.0) | <0.001 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 21 ± 9 | 20 ± 10 | 21 ± 7 | 0.410 |

| LVOT VTI (cm) | 16 ± 5 | 14 ± 4 | 21 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 41 ± 18 | 28 ± 7 | 60 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 47.0% | 36.4% | 62.3% | 0.002 |

| CAD | 45.8% | 58.6% | 27.5% | <0.001 |

| eGFR at admission | 60.0 (44.8–81.0) | 63.0 (46.0–81.5) | 54.0 (44.0–80.0) | 0.030 |

| In-hospital mortality | 10.1% | 9.1% | 11.6% | 0.788 |

| Virtue Index | 0.098 (0.057–0.190) | 0.135 (0.069–0.215) | 0.075 (0.049–0.110) | <0.001 |

| Group | Predictor | n | Events | AUC | CI 95% | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFrEF | Virtue Index | 99 | 9 | 0.584 | 0.364 to 0.791 | 0.441 |

| HFrEF | RV–RA gradient | 105 | 9 | 0.532 | 0.463 to 0.724 | 0.631 |

| HFrEF | TAPSE | 105 | 9 | 0.583 | 0.454 to 0.770 | 0.303 |

| HFrEF | LVOT VTI | 102 | 9 | 0.700 | 0.530 to 0.850 | 0.014 |

| HFpEF | Virtue Index | 69 | 8 | 0.704 | 0.536 to 0.852 | 0.011 |

| HFpEF | RV–RA gradient | 76 | 8 | 0.724 | 0.542 to 0.902 | 0.015 |

| HFpEF | TAPSE | 76 | 8 | 0.637 | 0.457 to 0.891 | 0.216 |

| HFpEF | LVOT VTI | 71 | 8 | 0.669 | 0.456 to 0.861 | 0.102 |

| Group | N_Pairs | Spearman_rho | CI 95% | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFrEF | 96 | 0.191 | −0.006 to 0.384 | 0.061 |

| HFpEF | 66 | 0.380 | 0.134 to 0.580 | 0.002 |

| Group | Comparison | Delta_AUC (Virtue—X) | Z | p-Value | N_Common |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFrEF | Virtue vs. RV–RA gradient | 0.052 | 0.407 | 0.684 | 99 |

| HFrEF | Virtue vs. TAPSE | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.994 | 99 |

| HFrEF | Virtue vs. LVOT VTI | −0.116 | −0.894 | 0.372 | 99 |

| HFpEF | Virtue vs. RV–RA gradient | −0.020 | −0.186 | 0.852 | 69 |

| HFpEF | Virtue vs. TAPSE | 0.067 | 0.504 | 0.614 | 69 |

| HFpEF | Virtue vs. LVOT VTI | 0.035 | 0.277 | 0.782 | 69 |

| Group | n | AUC_Virtue | AUC_NT-proBNP | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFrEF | 99 | 0.583 | 0.744 | 0.040 |

| HFpEF | 69 | 0.705 | 0.838 | 0.050 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popescu, D.-C.; Ciobanu, M.; Țînț, D.; Nechita, A.-C. The VIRTUE Index: A Novel Echocardiographic Marker Integrating Right–Left Ventricular Hemodynamics in Acute Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248803

Popescu D-C, Ciobanu M, Țînț D, Nechita A-C. The VIRTUE Index: A Novel Echocardiographic Marker Integrating Right–Left Ventricular Hemodynamics in Acute Heart Failure. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248803

Chicago/Turabian StylePopescu, Dan-Cristian, Mara Ciobanu, Diana Țînț, and Alexandru-Cristian Nechita. 2025. "The VIRTUE Index: A Novel Echocardiographic Marker Integrating Right–Left Ventricular Hemodynamics in Acute Heart Failure" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248803

APA StylePopescu, D.-C., Ciobanu, M., Țînț, D., & Nechita, A.-C. (2025). The VIRTUE Index: A Novel Echocardiographic Marker Integrating Right–Left Ventricular Hemodynamics in Acute Heart Failure. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248803