Inhaled Treprostinil: Improvements in Hemodynamics and Quality of Life for Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension on Dual or Triple Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Measurements

2.2. RHC

2.3. QoL Analysis

2.4. Statical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

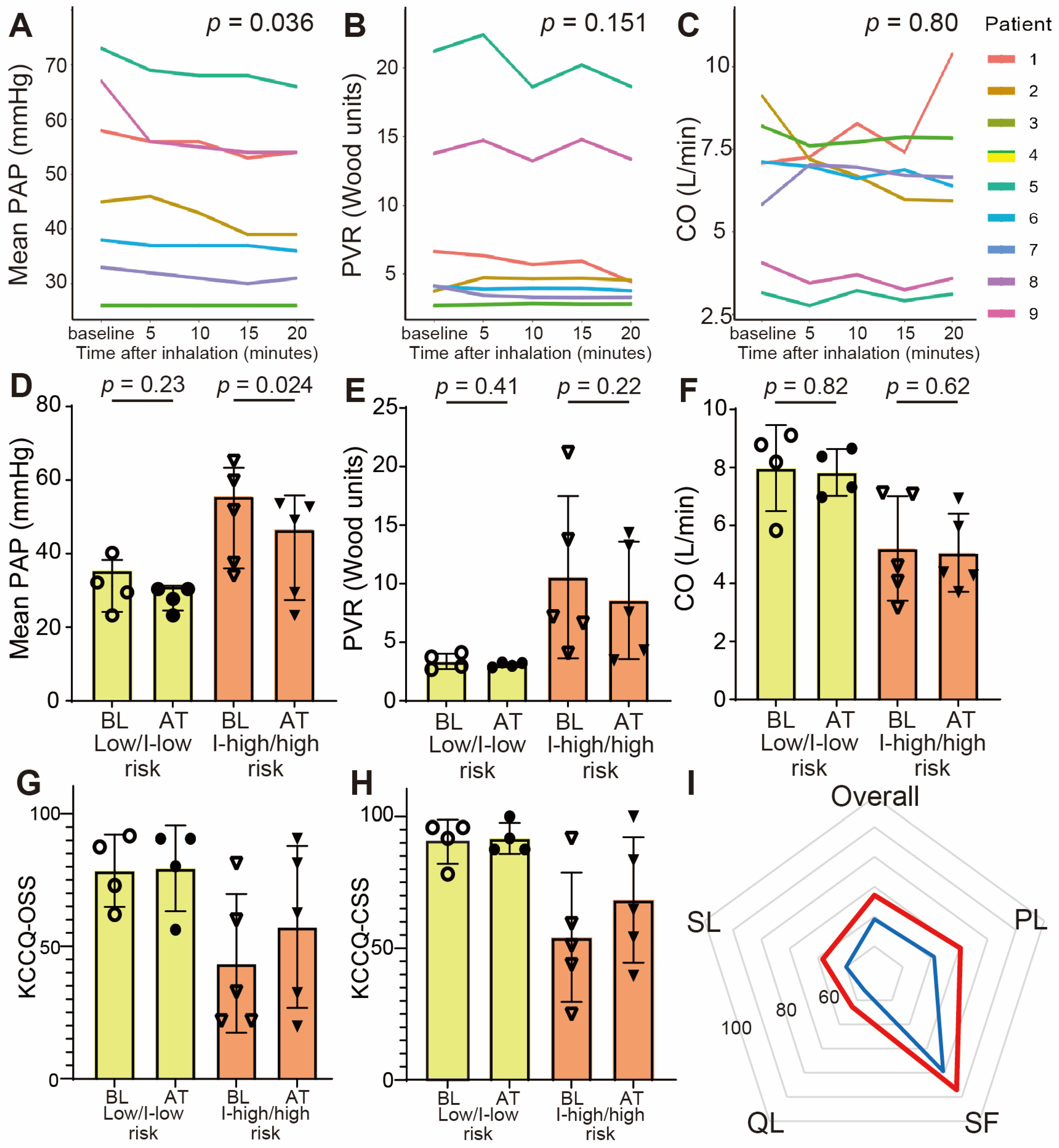

3.2. Acute Response of Inhaled Treprostinil

3.3. Hemodynamic Changes at 3 Months

3.4. Exercise Tolerance

3.5. Quality of Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CO | cardiac output |

| ERA | endothelin receptor antagonists |

| KCCQ | Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire |

| PAH | Pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| PAP | pulmonary artery pressure |

| PAWP | pulmonary artery wedge pressure |

| PDE5 | phosphodiesterase 5 |

| PVR | pulmonary vascular resistance |

| QoL | quality of life |

| RHC | right heart catheterization |

| sGC | soluble guanylate cyclase |

| 6MWD | 6 min walking distance |

References

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alonzo, G.E.; Barst, R.J.; Ayres, S.M.; Bergofsky, E.H.; Brundage, B.H.; Detre, K.M.; Fishman, A.P.; Goldring, R.M.; Groves, B.M.; Kernis, J.T.; et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Results from a national prospective registry. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991, 115, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, V.V.; Benza, R.L.; Rubin, L.J.; Channick, R.N.; Voswinckel, R.; Tapson, V.F.; Robbins, I.M.; Olschewski, H.; Rubenfire, M.; Seeger, W. Addition of inhaled treprostinil to oral therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwana, M.; Abe, K.; Kinoshita, H.; Matsubara, H.; Minatsuki, S.; Murohara, T.; Sakao, S.; Shirai, Y.; Tahara, N.; Tsujino, I.; et al. Efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of inhaled treprostinil in Japanese patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2023, 13, e12198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.M.; Gaine, S.P.; Gerges, C.; Jing, Z.C.; Mathai, S.C.; Tamura, Y.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Sitbon, O. Treatment algorithm for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2401325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardi, F.; Boucly, A.; Benza, R.; Frantz, R.; Mercurio, V.; Olschewski, H.; Rådegran, G.; Rubin, L.J.; Hoeper, M.M. Risk stratification and treatment goals in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2401323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K.; Adachi, S.; Nishiyama, I.; Yoshida, M.; Nakano, Y.; Murohara, T. Inhaled iloprost induces long-term beneficial hemodynamic changes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension receiving combination therapy. Pulm. Circ. 2022, 12, e12074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Xie, F. Efficacy and safety of iloprost in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. 2024, 64, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonneau, G.; Barst, R.J.; Galie, N.; Naeije, R.; Rich, S.; Bourge, R.C.; Keogh, A.; Oudiz, R.; Frost, A.; Blackburn, S.D.; et al. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of treprostinil, a prostacyclin analogue, in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benza, R.L.; Seeger, W.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Channick, R.N.; Voswinckel, R.; Tapson, V.F.; Robbins, I.M.; Olschewski, H.; Rubin, L.J. Long-term effects of inhaled treprostinil in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: The Treprostinil Sodium Inhalation Used in the Management of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (TRIUMPH) study open-label extension. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2011, 30, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, R.T.; Levine, D.J.; Bourge, R.C.; De Souza, S.A.; Rosenzweig, E.B.; Alnuaimat, H.; Burger, C.; Mathai, S.C.; Leedom, N.; DeAngelis, K.; et al. An observational study of inhaled-treprostinil respiratory-related safety in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2016, 6, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waxman, A.; Restrepo-Jaramillo, R.; Thenappan, T.; Ravichandran, A.; Engel, P.; Bajwa, A.; Allen, R.; Feldman, J.; Argula, R.; Smith, P.; et al. Inhaled Treprostinil in Pulmonary Hypertension Due to Interstitial Lung Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spertus, J.A.; Jones, P.G.; Sandhu, A.T.; Arnold, S.V. Interpreting the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in Clinical Trials and Clinical Care: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2379–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.P.; Porter, C.B.; Bresnahan, D.R.; Spertus, J.A. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: A new health status measure for heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 35, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, V.P.; Strom, J.B.; Gami, A.; Beussink-Nelson, L.; Patel, R.; Michos, E.D.; Shah, S.J.; Freed, B.H.; Mukherjee, M. Optimal Method for Assessing Right Ventricular to Pulmonary Arterial Coupling in Older Healthy Adults: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 222, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Azar, J.; Farha, S.; Goyanes, A.M.; Lane, J.E.; Paul, D.; Highland, K.B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Tonelli, A.R. Efficacy and determinants of response to inhaled treprostinil in pulmonary hypertension-interstitial lung disease. Respir. Med. 2024, 234, 107835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassady, S.J.; Ramani, G.V.; Wu, B.; Morland, K.; Burger, C.D. Real-World Comparison of Patients with PH-ILD Initiating Inhaled Treprostinil Versus Patients Who Remain Untreated. Pulm. Circ. 2025, 15, e70203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, V.; Farber, H.W.; Highland, K.B.; Hemnes, A.R.; Chakinala, M.M.; Chin, K.M.; Han, M.; Cho, M.; Tobore, T.; Rahman, M.; et al. Disease characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension treated with selexipag in real-world settings from the SPHERE registry (SelexiPag: tHe usErs dRug rEgistry). J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoi, M.; Hiraide, T.; Shinya, Y.; Momota, H.; Fukui, S.; Kawakami, M.; Fukuda, K.; Kataoka, M. Impact of additional selexipag on prostacyclin infusion analogs in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2022, 36, 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, J.; Corris, P.; Gaine, S.; Gibbs, J.S.; Kiely, D.G.; Harries, C.; Pollock, V.; Armstrong, I. emPHasis-10: Development of a health-related quality of life measure in pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 43, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, R.; Keogh, A.M.; Byth, K.; O’Loughlin, A. Comparison and validation of three measures of quality of life in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Intern. Med. J. 2006, 36, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollister, D.; Shaffer, S.; Badesch, D.B.; Filusch, A.; Hunsche, E.; Schüler, R.; Wiklund, I.; Peacock, A. Development of the Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension-Symptoms and Impact (PAH-SYMPACT®) questionnaire: A new patient-reported outcome instrument for PAH. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, Y.; Kumamaru, H.; Abe, K.; Satoh, T.; Miyata, H.; Ogawa, A.; Tanabe, N.; Hatano, M.; Yao, A.; Tsujino, I.; et al. Improvements in French risk stratification score were correlated with reductions in mean pulmonary artery pressure in pulmonary arterial hypertension: A subanalysis of the Japan Pulmonary Hypertension Registry (JAPHR). BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient | Age (Years) | Sex | Diagnosis | BMI (kg/m2) | WHO-FC | ESC/ERS Risk Stratification | Medications | BNP (pg/mL) | RV FAC (%) | Mean PAP (mmHg) | PVR (Wood Units) | CO (L/min) | PAWP (mmHg) | SaO2 (%) | SvO2 (%) | 6MWD (m) | KCCQ-12 Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | F | IPAH | 25.8 | III | intermediate–high | Macitentan 10 mg Tadatafil 40 mg Selexipag 3.2 mg | 39.3 | 18 | 58 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 11 | 92.4 (**) | 77.4 (**) | 320 | 21.9 |

| 2 | 35 | M | HPAH | 25.1 | II | low | Macitentan 10 mg Riociguat 7.5 mg Selexipag 3.2 mg | 16.4 | 39.3 | 45 | 3.7 | 9.1 | 11 | 95.4 | 80.7 | 552 | 62 |

| 3 | 46 | F | CHD-PAH * | 20.4 | II | intermediate–low | Macitentan 10 mg Tadatafil 40 mg Selexipag 3.2 mg | 17.6 | 36.6 | 26 | 2.7 | 8.2 | 4 | 94.9 | 76.9 | 430 | 72.9 |

| 4 | 48 | F | HPAH | 21.2 | III | intermediate–high | Macitentan 10 mg Tadatafil 40 mg | 361.8 | 24.6 | 73 | 21.2 | 3.2 | 8 | 96.1 | 58.9 | 425 | 81.3 |

| 5 | 72 | F | HPAH | 21.3 | III | intermediate–high | Macitentan 10 mg Riociguat 7.5 mg Selexipag 3.2 mg | 297 | 36.4 | 38 | 4.1 | 7.1 | 9 | 93.1 | 77 | 388 | 59.9 |

| 6 | 44 | M | IPAH | 28.3 | II | low | Macitentan 10 mg Riociguat 7.5 mg Selexipag 3.2 mg | 6.8 | 28.9 | 33 | 4.1 | 5.8 | 8 | 97.4 | 74.2 | 455 | 87.5 |

| 7 | 69 | F | IPAH | 17.7 | IV | high | Macitentan 10 mg Riociguat 7.5 mg Selexipag 3.2 mg | 163.9 | 34.4 | 42 | 7.2 | 4.6 | 7 | 97.3 | 71.1 | NA | 32.8 |

| 8 | 40 | F | IPAH | 19.1 | II | low | Macitentan 10 mg Riociguat 7.5 mg Selexipag 3.2 mg | 23.7 | 36.3 | 36 | 3 | 8.8 | 10 | 95.3 | 78.7 | 675 | 91.7 |

| 9 | 76 | M | HPAH | 16.2 | III | high | Macitentan 10 mg Riociguat 7.5 mg Selexipag 3.2 mg | 294.5 | 18.2 | 67 | 13.8 | 4.1 | 8 | 97.6 | 73.8 | NA | 21.9 |

| Baseline | After 3 Months | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean BP (mmHg) | 74.3 ± 7.4 | 81.2 ± 9.8 | 0.0972 |

| Mean PAP (mmHg) | 46.4 ± 16.1 | 39.8 ± 14.1 | 0.014 |

| PVR (WU) | 7.4 ± 6.2 | 6.1 ± 4.6 | 0.155 |

| CO (L/min) | 6.4 ± 2.1 | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 0.636 |

| PAWP (mmHg) | 8.4 ± 2.2 | 7.0 ± 2.1 | 0.105 |

| SaO2 (%) | 95.5 ± 1.9 | 93.5 ± 4.4 | 0.407 |

| SvO2 (%) | 74.3 ± 6.4 | 71.1 ± 7.3 | 0.075 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 39.3 [17.6, 294.5] | 22.3 [16.7, 163.1] | 0.812 |

| LVEF (%) | 65.3 ± 10.0 | 68.1 ± 5.7 | 0.407 |

| RVFAC (%) | 30.3 ± 8.2 | 30.3 ± 9.1 | 1 |

| 6MWD (m) | 464 ± 117 | 464 ± 114 | 1 |

| peak VO2 (mL/kg/min) | 16.0 ± 4.2 | 17.5 ± 5.6 | 0.419 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 39.7 ± 5.5 | 38.1 ± 2.7 | 0.59 |

| %VC | 94.9 ± 9.2 | 95.7 ± 12.4 | 0.447 |

| %FVC | 94.8 ± 11.7 | 95.3 ± 12.1 | 0.8 |

| FEV1.0% | 67.2 ± 9.4 | 66.1 ± 5.6 | 0.554 |

| %DLco | 58.9 ± 11.7 | 60.8 ± 14.2 | 0.272 |

| %DLco/VA | 64.1 ± 12.2 | 65.5 ± 11.9 | 0.353 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ikegami, S.; Hiraide, T.; Maeda, T.; Momoi, M.; Shinya, Y.; Anzai, A.; Shiraishi, Y.; Katsumata, Y.; Ieda, M. Inhaled Treprostinil: Improvements in Hemodynamics and Quality of Life for Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension on Dual or Triple Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8776. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248776

Ikegami S, Hiraide T, Maeda T, Momoi M, Shinya Y, Anzai A, Shiraishi Y, Katsumata Y, Ieda M. Inhaled Treprostinil: Improvements in Hemodynamics and Quality of Life for Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension on Dual or Triple Therapy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8776. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248776

Chicago/Turabian StyleIkegami, Shogo, Takahiro Hiraide, Takashi Maeda, Mizuki Momoi, Yoshiki Shinya, Atsushi Anzai, Yasuyuki Shiraishi, Yoshinori Katsumata, and Masaki Ieda. 2025. "Inhaled Treprostinil: Improvements in Hemodynamics and Quality of Life for Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension on Dual or Triple Therapy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8776. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248776

APA StyleIkegami, S., Hiraide, T., Maeda, T., Momoi, M., Shinya, Y., Anzai, A., Shiraishi, Y., Katsumata, Y., & Ieda, M. (2025). Inhaled Treprostinil: Improvements in Hemodynamics and Quality of Life for Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension on Dual or Triple Therapy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8776. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248776