Validity of the Arabic Version of the PROMIS Anxiety and PROMIS Depression in Cancer Questionnaires: Measuring Depression and Anxiety in Oncologic Patients in Saudi Arabia—A Rasch Analysis Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Outcome Measures

2.2. Phase 1: Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the PROMIS-Ca-D

2.3. Phase 2: Rasch Analysis of the PROMIS-Ca-D and PROMIS-Ca-A Questionnaires

Technical Details of the Rasch Analysis Procedure

- Categories functioning,

- Data-model fit,

- Questionnaire’s dimensionality,

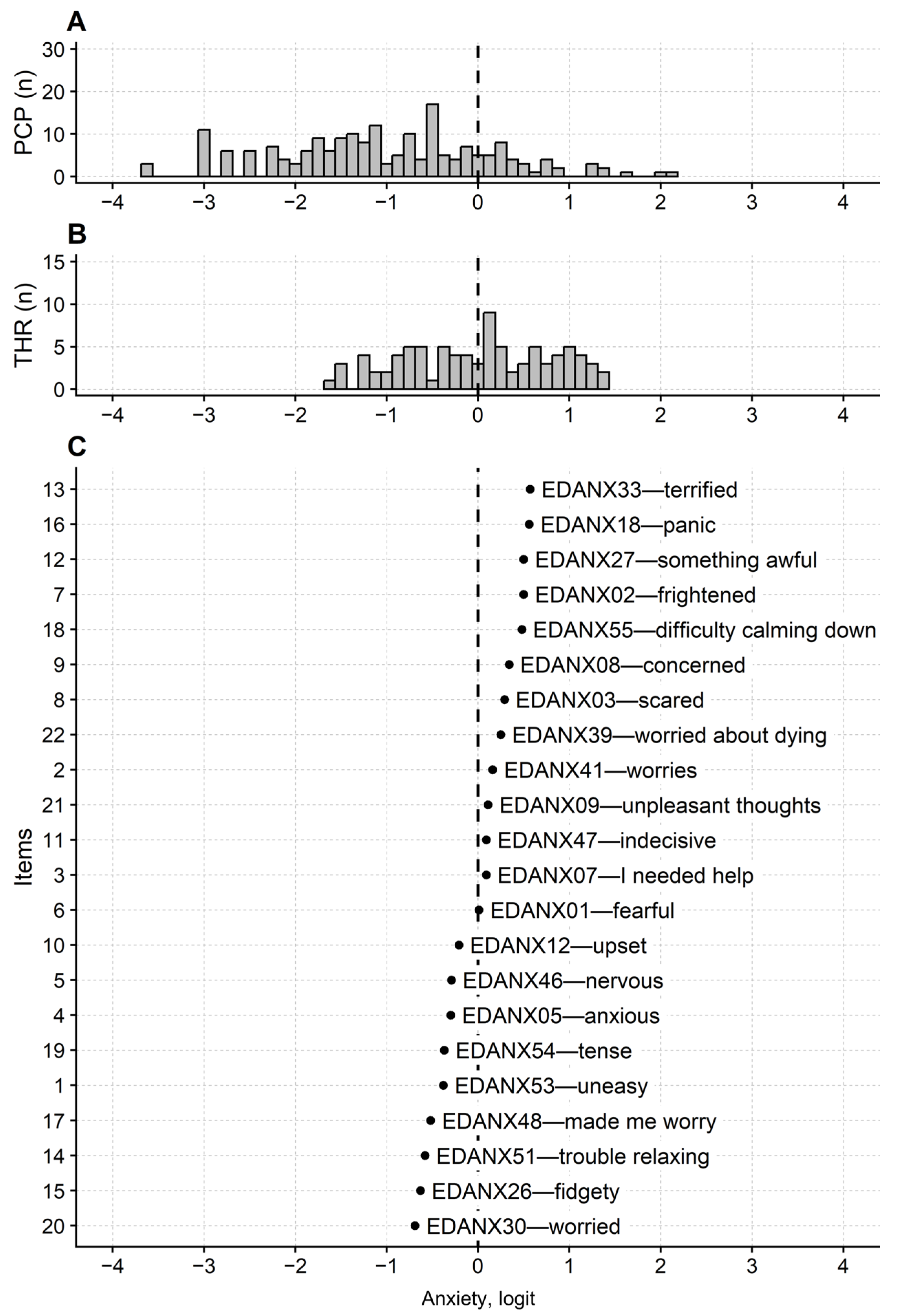

- Questionnaire’s maps,

- Differential Item Functioning (DIF) and

- Persons’ measures reliability.

3. Results

Rasch Analysis of the PROMIS-Ca-D and PROMIS-Ca-A Questionnaires

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CTT | Classical Test Theory |

| DASS | Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale |

| DIF | Differential Item Functioning |

| FACIT | Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| IRT | Item Response Theory |

| MNSQ | Mean square |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PCs | Principal components |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire—9 items |

| PROMIS | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System |

| PROMIS-Ca-A | PROMIS Anxiety in Cancer questionnaire |

| PROMIS-Ca-D | PROMIS Depression in Cancer questionnaire |

| PROMs | Patient-reported outcome measures |

| RA | Rasch Analysis |

| RSM | Rating Scale Model |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| ZSTD | z-standardized statistics |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbakhsh, N.; Moudi, S.; Abbasian, S.; Khafri, S. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety among Cancer Patients. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 5, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.R. Depression in Cancer Patients: Pathogenesis, Implications and Treatment (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2015, 9, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesio, L.; Scarano, S.; Hassan, S.; Kumbhare, D.; Caronni, A. Why Questionnaire Scores Are Not Measures: A Question-Raising Article. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 102, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almigbal, T.H.; Almutairi, K.M.; Fu, J.B.; Vinluan, J.M.; Alhelih, E.; Alonazi, W.B.; Batais, M.A.; Alodhayani, A.A.; Mubaraki, M.A. Assessment of Psychological Distress among Cancer Patients Undergoing Radiotherapy in Saudi Arabia. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clover, K.; Lambert, S.D.; Oldmeadow, C.; Britton, B.; King, M.T.; Mitchell, A.J.; Carter, G. PROMIS Depression Measures Perform Similarly to Legacy Measures Relative to a Structured Diagnostic Interview for Depression in Cancer Patients. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el-Rufaie, O.E.; Absood, G. Validity Study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale among a Group of Saudi Patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 151, 687–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, M.T.; Lovibond, P.; Laube, R.; Megahead, H.A. Psychometric Properties of an Arabic Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS). Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2017, 27, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B. Validation and Utility of a Self-Report Version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 1999, 282, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.; Al Zaid, K.; Al Faris, E. Screening for Somatization and Depression in Saudi Arabia: A Validation Study of the PHQ in Primary Care. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2002, 32, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Harrasi, S.M.; Al-Awaisi, H.; Al Balushi, M.; Al Balushi, L.; Al Kharusi, S. Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Its Association with Depressive Symptoms Among Adult Omani Female Breast Cancer Survivors. Int. J. Womens Health 2025, 17, 2625–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Hakiri, A.; Fendri, S.; Balti, M.; Labbane, R.; Cheour, M. Evaluation of Religious Coping in Tunisian Muslim Women with Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 1839–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Gagin, R.; Cinamon, T.; Stein, T.; Moscovitz, M.; Kuten, A. Translating “distress” and Screening for Emotional Distress in Multicultural Cancer Patients in Israel. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Ahmed, A.; Sharaf, A.; Kawakami, N.; Abdeldayem, S.M.; Green, J. The Arabic Version of The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21: Cumulative Scaling and Discriminant-Validation Testing. Asian J. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.; Riley, W.; Stone, A.; Rothrock, N.; Reeve, B.; Yount, S.; Amtmann, D.; Bode, R.; Buysse, D.; Choi, S.; et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Developed and Tested Its First Wave of Adult Self-Reported Health Outcome Item Banks: 2005–2008. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.; Choi, S.; Garcia, S.; Cook, K.F.; Rosenbloom, S.; Lai, J.-S.; Tatum, D.S.; Gershon, R. Setting Standards for Severity of Common Symptoms in Oncology Using the PROMIS Item Banks and Expert Judgment. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 2651–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothmund, M.; Pilz, M.J.; Egeter, N.; Lidington, E.; Piccinin, C.; Arraras, J.I.; Grønvold, M.; Holzner, B.; van Leeuwen, M.; Petersen, M.A.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for Emotional Functioning in Cancer Patients: Content Comparison of the EORTC CAT Core, FACT-G, HADS, SF-36, PRO-CTCAE, and PROMIS Instruments. Psychooncology 2023, 32, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recklitis, C.J.; Blackmon, J.E.; Chang, G. Screening Young Adult Cancer Survivors with the PROMIS Depression Short Form (PROMIS-D-SF): Comparison with a Structured Clinical Diagnostic Interview. Cancer 2020, 126, 1568–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.K.; Peipert, J.D.; Cella, D.; Yost, K.J.; Eton, D.T.; Novotny, P.J.; Sloan, J.A.; Dueck, A.C. Identifying Meaningful Change on PROMIS Short Forms in Cancer Patients: A Comparison of Item Response Theory and Classic Test Theory Frameworks. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 1355–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesio, L.; Caronni, A.; Kumbhare, D.; Scarano, S. Interpreting Results from Rasch Analysis 1. The “Most Likely” Measures Coming from the Model. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 46, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesio, L.; Caronni, A.; Simone, A.; Kumbhare, D.; Scarano, S. Interpreting Results from Rasch Analysis 2. Advanced Model Applications and the Data-Model Fit Assessment. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 46, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhahi, M.I.; Bakhsh, H.R.; Bin Sheeha, B.H.; Alhasani, R. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation of an Arabic Version of PROMIS® of Dyspnea Activity Motivation, Requirement Item Pool and Sleep-Related Impairments Item Bank. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2024, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, H.R.; Aldhahi, M.I.; Aldajani, N.S.; Davalji Kanjiker, T.S.; Bin Sheeha, B.H.; Alhasani, R. Arabic Translation and Rasch Validation of PROMIS Anxiety Short Form among General Population in Saudi Arabia. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, H.R.; Aldajani, N.S.; Sheeha, B.B.; Aldhahi, M.I.; Alsomali, A.A.; Alhamrani, G.K.; Alamri, R.Z.; Alhasani, R. Arabic Translation and Psychometric Validation of PROMIS General Life Satisfaction Short Form in the General Population. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.F.; Cella, D.; Clauser, S.B.; Flynn, K.E.; Lad, T.; Lai, J.-S.; Reeve, B.B.; Smith, A.W.; Stone, A.A.; Weinfurt, K. Standardizing Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment in Cancer Clinical Trials: A Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Initiative. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 5106–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresi, J.A.; Ocepek-Welikson, K.; Kleinman, M.; Ramirez, M.; Kim, G. Measurement Equivalence of the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® (PROMIS®) Anxiety Short Forms in Ethnically Diverse Groups. Psychol. Test. Assess. Model. 2016, 58, 183–219. [Google Scholar]

- Eremenco, S.L.; Cella, D.; Arnold, B.J. A Comprehensive Method for the Translation and Cross-Cultural Validation of Health Status Questionnaires. Eval. Health Prof. 2005, 28, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. Sample Size and Item Calibration Stability. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 7, 328. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J.M. Winsteps® Rasch Measurement Computer Program User’s Guide; Version 5.6.0.; Winsteps.com: Portland, OR, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B.; Mokkink, L.B.; Knol, D.L. Validity. In Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide; Practical Guides to Biostatistics and Epidemiology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 150–201. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom, D.; Mellenbergh, G.J.; van Heerden, J. The Concept of Validity. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 111, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linacre, J. Category Disordering (Disordered Categories) vs. Threshold Disordering (Disordered Thresholds). Rasch Meas. Trans. 1999, 13, 675. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J. Category, Step and Threshold: Definitions & Disordering. Rasch Meas. Trans. 2001, 15, 794. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J.M. Transitional Categories and Usefully Disordered Thresholds. Online Educ. Res. J. 2010, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J.M. What Do Infit and Outfit, Mean-Square and Standardized Mean. Rasch Meas. Trans. 2002, 16, 878. [Google Scholar]

- Dimensionality: PCAR Contrasts & Variances: Winsteps Help. Available online: https://www.winsteps.com/winman/principalcomponents.htm (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Linacre, J.M. DIF—DPF—Bias—Interactions Concepts. Available online: https://www.winsteps.com/winman/difconcepts.htm (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Tennant, A.; Pallant, J. DIF Matters: A Practical Approach to Test If Differential Item Functioning Makes a Difference. Rasch Meas. Trans. 2007, 20, 1082–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B.D.; Stone, M. Measurement Essentials; Wide Range Inc.: Singapore, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Caronni, A.; Picardi, M.; Scarano, S.; Rota, V.; Amadei, M. Improving Single-Subject Change Assessment: Deriving the Minimal Detectable Change of Questionnaires’ Ordinal Scores from Rasch Analysis Measures. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, A.; Conaghan, P.G. The Rasch Measurement Model in Rheumatology: What Is It and Why Use It? When Should It Be Applied, and What Should One Look for in a Rasch Paper? Arthritis Care Res. 2007, 57, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitzsch, A.; Kiefer, T.; Wu, M. TAM: Test Analysis Modules. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=TAM (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Vanhoutte, E.K.; Faber, C.G.; Van Nes, S.I.; Jacobs, B.C.; Van Doorn, P.A.; Van Koningsveld, R.; Cornblath, D.R.; Van Der Kooi, A.J.; Cats, E.A.; Van Den Berg, L.H.; et al. Modifying the Medical Research Council Grading System through Rasch Analyses. Brain 2012, 135, 1639–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, A.; Küçükdeveci, A.A. Application of the Rasch Measurement Model in Rehabilitation Research and Practice: Early Developments, Current Practice, and Future Challenges. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2023, 4, 1208670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asamoah, N.A.B.; Turner, R.C.; Lo, W.-J.; Crawford, B.L.; McClelland, S.; Jozkowski, K.N. Evaluating Item Response Format and Content Using Partial Credit Trees in Scale Development. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 2025, 13, 280–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.J.; Wu, M.L.; Wilson, M. The Rasch Rating Model and the Disordered Threshold Controversy. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2012, 72, 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrich, D. An Expanded Derivation of the Threshold Structure of the Polytomous Rasch Model That Dispels Any “Threshold Disorder Controversy”. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 78–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, T.; Kozlowski, A.J.; Johnston, M.V.; Weaver, J.; Terhorst, L.; Grampurohit, N.; Juengst, S.; Ehrlich-Jones, L.; Heinemann, A.W.; Melvin, J.; et al. Rasch Reporting Guideline for Rehabilitation Research (RULER): The RULER Statement. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 1477–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Winckel, A.; Kozlowski, A.J.; Johnston, M.V.; Weaver, J.; Grampurohit, N.; Terhorst, L.; Juengst, S.; Ehrlich-Jones, L.; Heinemann, A.W.; Melvin, J.; et al. Reporting Guideline for RULER: Rasch Reporting Guideline for Rehabilitation Research: Explanation and Elaboration. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HealthMeasures. Anxiety Measure Differences: A Brief Guide to Differences Between the PROMIS® Anxiety Instruments; HealthMeasures: Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- HealthMeasures. Depression Measure Differences: A Brief Guide to Differences Between the PROMIS® Depression Instruments; HealthMeasures: Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Caronni, A.; Scarano, S. Generalisability of the Barthel Index and the Functional Independence Measure: Robustness of Disability Measures to Differential Item Functioning. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 47, 2134–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, N.F.C.; de Melo Costa Pinto, R.; da Silva Mendonça, T.M.; da Silva, C.H.M. Psychometric Validation of PROMIS® Anxiety and Depression Item Banks for the Brazilian Population. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W.P., Jr. IRT and Confusion about Rasch Measurement. Rasch Meas. Trans. 2010, 24, 1288. [Google Scholar]

- Negrini, S.; Zaina, F.; Buyukaslan, A.; Fortin, C.; Karavidas, N.; Kotwicki, T.; Korbel, K.; Parent, E.; Sanchez-Raya, J.; Shearer, K.; et al. Cross-Cultural Validation of the Italian Spine Youth Quality of Life Questionnaire: The ISYQOL International. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 59, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total (N = 30) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, Mean (SD) | 35.2 (10.5) |

| Sex, N of females (%) | 15 (50%) |

| Educational level, N (%) | |

| High School | 11 (37%) |

| Diploma | 7 (23%) |

| Undergraduate | 12 (40%) |

| Variables | Total (N = 213) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, Mean (SD) | 49 (15.6) |

| Sex, N of females (%) | 123 (58%) |

| BMI, kg/m2, Mean (SD) | 25.7 (5.3) |

| Diagnosis, N (%) | |

| Breast | 37 (17.4) |

| Colon | 32 (15.0) |

| Leukemia | 22 (10.3) |

| Liver | 17 (8.0) |

| Lymphoma | 12 (5.6) |

| Not specified | 20 (9.4) |

| Time from diagnosis, years, Mean (SD) | 2.35 (2.61) |

| Educational level, N (%) | |

| Uneducated | 21 (10%) |

| Primary or secondary school | 56 (26%) |

| High School | 72 (34%) |

| University | 64 (30%) |

| Employment status, N (%) | |

| Student or worker | 83 (39%) |

| Retired | 29 (14%) |

| Unemployed | 101 (47%) |

| Marital status, N (%) | |

| Married | 135 (63%) |

| Alone (single, divorced or widowed) | 78 (37%) |

| Category Label | Observed Average | Modal Thresholds | Infit MnSq | Outfit MnSq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROMIS-Ca-A | ||||

| 1 Never | −1.88 | None | 0.92 | 0.99 |

| 2 Rarely | −0.91 | −0.39 | 1.01 | 0.79 |

| 3 Sometimes | −0.37 | −0.92 (*) | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| 4 Often | 0.09 | 0.52 | 1.10 | 1.22 |

| 5 Always | 0.71 | 0.79 | 1.23 | 1.37 |

| PROMIS-Ca-D | ||||

| 1 Never | −2.00 | None | 0.90 | 0.99 |

| 2 Rarely | −0.83 | −0.11 | 1.17 | 0.78 |

| 3 Sometimes | −0.44 | −1.06 (*) | 0.99 | 0.94 |

| 4 Often | 0.11 | 0.36 | 1.05 | 1.15 |

| 5 Always | 0.63 | 0.80 | 1.21 | 1.33 |

| Item Number | Item Description | Calibration (SE) | Infit MnSq (Zstd) | Outfit MnSq (Zstd) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (13) EDANX33 | I felt terrified | 0.57 (0.09) | 0.85 (−1.25) | 0.82 (−0.87) |

| (16) EDANX18 | I had sudden feelings of panic | 0.56 (0.09) | 0.95 (−0.35) | 0.73 (−1.40) |

| (12) EDANX27 | I felt something awful would happen | 0.50 (0.09) | 0.81 (−1.68) | 0.82 (−0.89) |

| (7) EDANX02 | I felt frightened | 0.50 (0.09) | 0.96 (−0.32) | 0.82 (−0.93) |

| (18) EDANX55 | I had difficulty calming down | 0.48 (0.09) | 1.01 (0.08) | 0.80 (−1.05) |

| (9) EDANX08 | I was concerned about my mental health | 0.34 (0.9) | 1.25 (2.04) | 1.27 (1.46) |

| (8) EDANX03 | It scared me when I felt nervous | 0.29 (0.09) | 1.04 (0.42) | 0.90 (−0.53) |

| (22) EDANX39 | I worried about dying | 0.25 (0.09) | 1.27 (2.29) | 1.73 (3.53) |

| (2) EDANX41 | My worries overwhelmed me | 0.16 (0.08) | 0.89 (−1.05) | 1.05 (0.38) |

| (21) EDANX09 | I had unpleasant thoughts that wouldn’t leave my mind | 0.11 (0.08) | 0.94 (−0.52) | 0.84 (−1.00) |

| (3) EDANX07 | I felt like I needed help for my anxiety | 0.90 (0.8) | 1.10 (0.93) | 1.08 (0.53) |

| (11) EDANX47 | I felt indecisive | 0.90 (0.08) | 0.82 (−1.71) | 0.73 (−1.81) |

| (6) EDANX01 | I felt fearful | 0.10 (0.08) | 0.80 (−1.98) | 0.69 (−2.17) |

| (10) EDANX12 | I felt upset | −0.21(0.8) | 0.81 (−1.94) | 0.73 (−2.06) |

| (5) EDANX46 | I felt nervous | −0.29 (0.8) | 1.15 (1.45) | 1.24 (1.68) |

| (4) EDANX05 | I felt anxious | −0.30 (0.8) | 0.87 (−1.35) | 0.94 (−0.42) |

| (19) EDANX54 | I felt tense | −0.37 (0.8) | 0.73 (−2.92) | 0.82 (−1.37) |

| (1) EDANX53 | I felt uneasy | −0.38 (0.8) | 1.30 (2.76) | 1.52 (3.45) |

| (17) EDANX48 | Many situations made me worry | −0.52 (0.8) | 1.18 (1.77) | 1.31 (2.30) |

| (14) EDANX51 | I had trouble relaxing | −0.58 (0.8) | 1.41 (3.71 | 1.46 (3.27) |

| (15) EDANX26 | I felt fidgety | −0.63 (0.8) | 1.26 (2.48) | 1.46 (3.36) |

| (20) EDANX30 | I felt worried | −0.69 (0.8) | 1.04 (0.42) | 1.02 (0.17) |

| Item Number | Item Description | Calibration (SE) | Infit MnSq (Zstd) | Outfit MnSq (Zstd) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (19) EDDEP39 | I felt I had no reason to live | 0.84 (0.10) | 0.86 (−1.00) | 0.70 (−1.03) |

| (29) EDDEP38 | I felt unloved | 0.83 (0.10) | 1.07 (0.56) | 0.83 (−0.51) |

| (21) EDDEP46 | I felt pessimistic | 0.51 (0.09) | 0.83 (−1.37) | 0.57 (−1.92) |

| (10) EDDEP22 | I felt like a failure | 0.51 (0.09) | 0.82 (−1.48) | 0.68 (−1.35) |

| (20) EDDEP41 | I felt hopeless | 0.49 (0.09) | 0.62 (−3.42) | 0.45 (−2.71) |

| (9) EDDEP21 | I felt that I was to blame for things | 0.46 (0.09) | 1.30 (2.26) | 1.31 (1.21) |

| (13) EDDEP27 | I felt that no one needed me | 0.40 (0.09) | 1.17 (1.33) | 0.89 (−0.40) |

| (12) EDDEP26 | I felt disappointed in myself | 0.32 (0.09) | 0.79 (−1.79) | 0.61 (−1.92) |

| (1) EDDEP04 | I felt worthless | 0.25 (0.09) | 0.78 (−1.98) | 0.90 (−0.40) |

| (22) EDDEP48 | I felt my life was empty | 0.25 (0.09) | 0.79 (−1.80) | 0.72 (−1.32) |

| (2) EDDEP05 | I felt like I had nothing to look forward to | 0.18 (0.09) | 1.16 (1.33) | 1.36 (1.58) |

| (8) EDDEP19 | I felt like I wanted to give up everything | 0.14 (0.09) | 1.24 (1.91) | 1.43 (1.85) |

| (30) EDDEP55 | I felt like I needed help for my depression | 0.11 (0.09) | 1.33 (2.61) | 1.12 (0.60) |

| (6) EDDEP14 | I felt that I was not as good as other people | 0.08 (0.09) | 0.89 (−0.91) | 0.84 (−0.77) |

| (18) EDDEP36 | I felt unhappy | −0.06 (0.08) | 0.80 (−1.82) | 0.77 (−1.21) |

| (5) EDDEP09 | I felt that nothing could cheer me up | −0.07 (0.08) | 0.82 (−1.66) | 0.70 (−1.68) |

| (3) EDDEP06 | I felt helpless | −0.08 (0.08) | 0.86 (−1.31) | 0.87 (−0.66) |

| (15) EDDEP29 | I felt depressed | −0.10 (0.08) | 0.89 (−0.94) | 0.93 (−0.34) |

| (16) EDDEP31 | I felt discouraged about the future | −0.10 (0.08) | 0.83 (−1.52) | 1.10 (0.56) |

| (14) EDDEP28 | I felt lonely | −0.10 (0.08) | 1.05 (0.46) | 1.16 (0.88) |

| (24) EDDEP02 | I felt lonely even when I was with other people | −0.14 (0.08) | 0.68 (−3.22) | 0.57 (−2.72) |

| (23) EDDEP54 | I felt emotionally drained | −0.14 (0.08) | 1.09 (0.80) | 1.08 (0.46) |

| (11) EDDEP23 | I had trouble feeling close to people | −0.29 (0.08) | 1.16 (1.41) | 1.15 (0.89) |

| (17) EDDEP35 | I felt that the circumstances of my life were getting the better of me | −0.37 (0.08) | 0.85 (−1.41) | 0.90 (−0.60) |

| (26) EDDEP16 | I felt like crying | −0.46 (0.08) | 1.40 (3.32) | 1.75 (3.92) |

| (27) EDANG09 | I felt angry | −0.49 (0.08) | 1.20 (1.81) | 1.27 (1.65) |

| (7) EDDEP17 | I felt sad | −0.54 (0.08) | 1.10 (0.90) | 1.16 (1.05) |

| (4) EDDEP07 | I moved away from others (*) | −0.63 (0.08) | 1.61 (4.84) | 1.48 (2.86) |

| (28) EDANG29 | I felt quick to anger | −0.66 (0.08) | 1.34 (2.91) | 1.42 (2.56) |

| (25) EDDEP12 | I had mood swings | −1.14 (0.08) | 1.30 (2.65) | 1.43 (2.97) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakhsh, H.R.; Bin sheeha, B.; Tesio, L.; Simone, A.; Scarano, S.; Alowain, N.; Bin Dayel, G.A.; Aldhahi, M.I.; Alhasani, R.; Caronni, A. Validity of the Arabic Version of the PROMIS Anxiety and PROMIS Depression in Cancer Questionnaires: Measuring Depression and Anxiety in Oncologic Patients in Saudi Arabia—A Rasch Analysis Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8774. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248774

Bakhsh HR, Bin sheeha B, Tesio L, Simone A, Scarano S, Alowain N, Bin Dayel GA, Aldhahi MI, Alhasani R, Caronni A. Validity of the Arabic Version of the PROMIS Anxiety and PROMIS Depression in Cancer Questionnaires: Measuring Depression and Anxiety in Oncologic Patients in Saudi Arabia—A Rasch Analysis Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8774. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248774

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakhsh, Hadeel R., Bodor Bin sheeha, Luigi Tesio, Anna Simone, Stefano Scarano, Nouf Alowain, Ghada A. Bin Dayel, Monira I. Aldhahi, Rehab Alhasani, and Antonio Caronni. 2025. "Validity of the Arabic Version of the PROMIS Anxiety and PROMIS Depression in Cancer Questionnaires: Measuring Depression and Anxiety in Oncologic Patients in Saudi Arabia—A Rasch Analysis Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8774. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248774

APA StyleBakhsh, H. R., Bin sheeha, B., Tesio, L., Simone, A., Scarano, S., Alowain, N., Bin Dayel, G. A., Aldhahi, M. I., Alhasani, R., & Caronni, A. (2025). Validity of the Arabic Version of the PROMIS Anxiety and PROMIS Depression in Cancer Questionnaires: Measuring Depression and Anxiety in Oncologic Patients in Saudi Arabia—A Rasch Analysis Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8774. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248774