Atrial Dilated Cardiomyopathy: From Molecular Pathogenesis to Clinical Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Discussion and State-of-the-Art

- Patients with long-standing heart disease and prior supraventricular arrhythmias. In this cohort, AS was considered the final stage of myocardial fibrosis. Patients often progressed from transient atrial paralysis, still responsive to atrial pacing, to irreversible standstill. Histological examination of right atrial (RA) biopsies revealed diffuse fibrosis, supporting the notion that atrial paralysis can represent a nonspecific outcome of advanced structural remodelling.

- Patients with neuromuscular disorders. These included facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy [7,8,9], Charcot-Marie muscular dystrophy [10], an X-linked humeral-peroneal neuromuscular disease, Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) [11], and limb-girdle muscular dystrophy [12,13]. Remarkably, Woolliscroft described the first case in which permanent AS preceded overt skeletal muscle involvement, highlighting the arrhythmia as an early manifestation [3]. Autopsy data in this subgroup confirmed diffuse atrial fibrosis and myocardial scarring.

- Patients without prior cardiac or neuromuscular disease. In these cases, AS was discovered incidentally during evaluations for syncope, vertigo, or ischemic stroke, or at routine physical examination. Histological studies of RA and ventricular tissue revealed diffuse myocyte degeneration, interstitial expansion, and thickening of the RA endocardium [3].

4. Classification and Etiology

- Partial AS refers to cases in which residual excitability persists in discrete regions of the RA [20,21]. Diagnosis requires multipoint atrial recordings, as standard surface electrocardiography may fail to detect localized activity. This form is often secondary to organic heart disease—including valvular lesions, ischemic cardiomyopathy, or infiltrative processes—and may remain clinically silent for years. In symptomatic patients with significant bradyarrhythmias or chronotropic incompetence, permanent pacing is generally indicated.

- Total AS, by contrast, is defined by the complete absence of excitable atrial tissue and failure to elicit any atrial response to pacing [20]. This form carries a more severe prognosis due to its association with extensive structural remodelling and higher thromboembolic risk.

- The transient form is reversible and typically associated with acute conditions such as myocardial ischemia or infarction, myocarditis, electrolyte disturbances (particularly hyperkalaemia), hypoxia, digitalis or quinidine toxicity, electrical cardioversion, or recent cardiac surgery [29]. In these settings, atrial paralysis is a functional consequence of transient metabolic or inflammatory insults to the atrial myocardium rather than irreversible structural damage.

- The persistent or permanent form reflects chronic and irreversible loss of atrial excitability. It may arise idiopathically or in association with rheumatic heart disease, infiltrative cardiomyopathies, amyloidosis, diabetes mellitus, Ebstein’s anomaly, and hereditary neuromuscular disorders [1]. The electrocardiographic recognition of atrial paralysis now mandates the exclusion of EDMD, in which atrial arrhythmogenic pathology often precedes the clinical onset of skeletal muscle involvement.

5. Pathophysiology and Genetic Background

5.1. LMNA, DES, and EMD Gene Variants

5.2. SCN5A and RYR2 Gene Variants

5.3. NPPA Gene Variant

5.4. MYL4 Gene Variant

6. Role of Atrial Natriuretic Peptide (ANP) in Atrial Dilated Cardiomyopathy

7. Diagnosis, Management and Prognosis

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADCM | Atrial dilated cardiomyopathy |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| ARVC | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| ANP | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| AS | Atrial standstill |

| BrS | Brugada syndrome |

| Cx40 | Connexin40 |

| CPVT | Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia |

| EDMD | Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy |

| EMD | Emerin |

| DCM | Dilated Cardiomyopathy |

| DES | Desmin |

| LA | Left atrium |

| LMNA | Lamin A/C |

| LVNC | Left ventricular noncompaction |

| MYL4 | Myosin Light Chain 4 |

| NPPA | Natriuretic Peptide Precursor A |

| RA | Right atrium |

| RYR2 | Ryanodine receptor 2 |

| SCN5A | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 5 |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

References

- Marini, M.; Arbustini, E.; Disertori, M. Atrial standstill: A paralysis of cardiological relevance. Ital. Heart J. Suppl. 2004, 5, 681–686. [Google Scholar]

- Disertori, M.; Quintarelli, S.; Grasso, M.; Pilotto, A.; Narula, N.; Favalli, V.; Canclini, C.; Diegoli, M.; Mazzola, S.; Marini, M.; et al. Autosomal recessive atrial dilated cardiomyopathy with standstill evolution associated with mutation of Natriuretic Peptide Precursor A. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2013, 6, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolliscroft, J.; Tuna, N. Permanent atrial standstill: The clinical spectrum. Am. J. Cardiol. 1982, 49, 2037–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

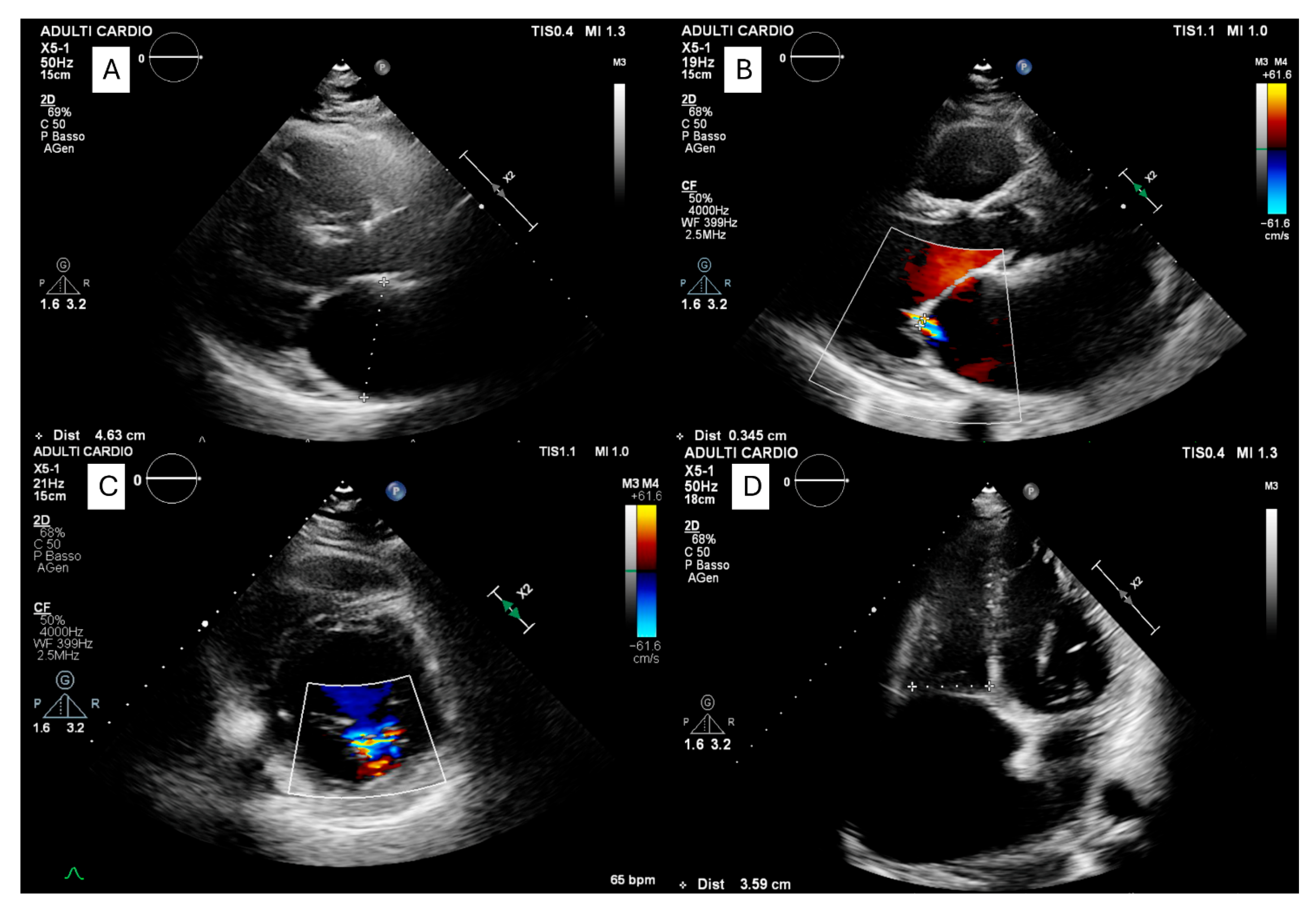

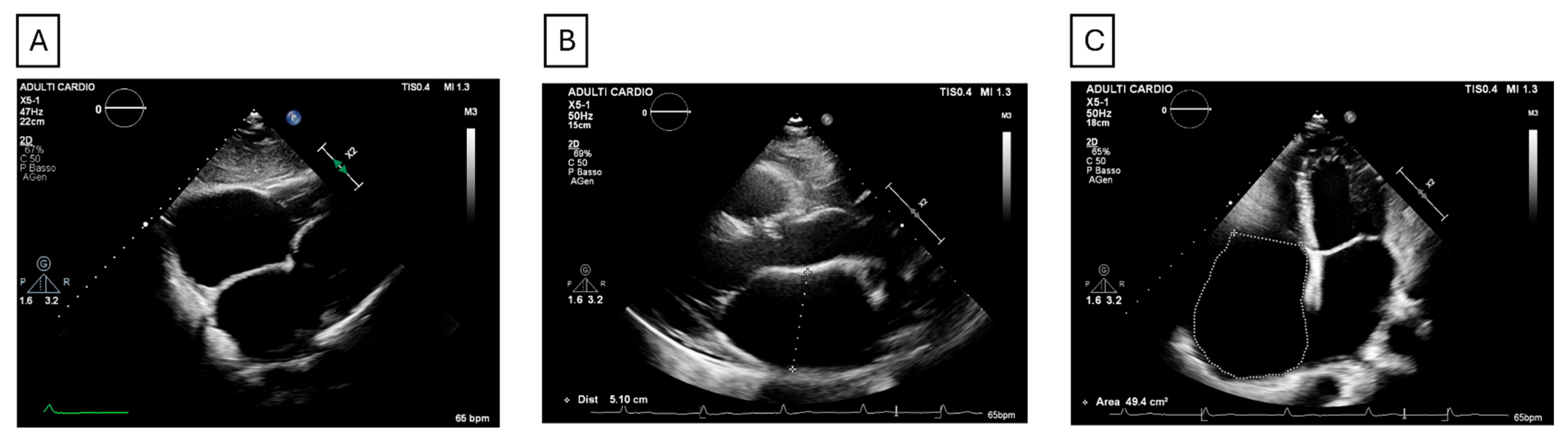

- Forleo, C.; Dicorato, M.M.; Carella, M.C.; Basile, P.; Dentamaro, I.; Santobuono, V.E.; Guaricci, A.I.; Resta, N.; Ciccone, M.M.; Arbustini, E. NPPA-Associated Atrial Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Genotypic and Phenotypic Insights From an Ultrarare Inherited Disorder. JACC Case Rep. 2025, 30, 105141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Cunha, P.; Antunes, D.O.; Laranjo, S.; Coutinho, A.; Abecasis, J.; Oliveira, M.M. Case report: Mutation in NPPA gene as a cause of fibrotic atrial myopathy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1149717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, I.; Brumlik, J.; Sodi Pallares, D. About an extraordinary case of permanent atrial palsy with Keith and Flack node degeneration. Arch. Inst. Cardiol. Mex. 1946, 16, 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, B.J.; Talley, R.C.; Johnson, C.; Nutter, D.O. Permanent paralysis of the atrium in a patient with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1973, 31, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, D.A.; Sinclair-Smith, B.C. Persistent Atrial Standstill. Am. J. Med. 1965, 39, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponnetto, S.; Pastorini, C.; Tirelli, G. Persistent atrial standstill in a patient affected with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Cardiologia 1968, 53, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, D.D.; Nutter, D.O.; Hopkins, L.C.; Dorney, E.R. Cardiac features of an unusual X-linked humeroperoneal neuromuscular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1975, 293, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, L.P.; Fetell, M.; Olarte, M.; Hays, A.; Singh, N.; Wanat, F.E. Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 1979, 5, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, J.H.; Diniz, M.C.; Miranda, D. Persistent atrial standstill with limb girdle muscular dystrophy. Cardiology 1978, 63, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappelli, A.; Gagna, C.; Fabris, F. Permanent atrial standstill in a patient suffering from progressive muscular dystrophy and diabetes mellitus. Minerva Cardioangiol. 1969, 17, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Disertori, M.; Guarnerio, M.; Vergara, G.; Del Favero, A.; Bettini, R.; Inama, G.; Rubertelli, M.; Furlanello, F. Familial endemic persistent atrial standstill in a small mountain community: Review of eight cases. Eur. Heart J. 1983, 4, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Balaji, S.; Till, J.; Shinebourne, E.A. Familial atrial standstill with coexistent atrial flutter. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1998, 21, 1841–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.K.; Subramanyan, R.; Tharakan, J.; Venkitachalam, C.G.; Balakrishnan, K.G. Familial total atrial standstill. Am. Heart J. 1992, 123, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disertori, M.; Mase, M.; Marini, M.; Mazzola, S.; Cristoforetti, A.; Del Greco, M.; Kottkamp, H.; Arbustini, E.; Ravelli, F. Electroanatomic mapping and late gadolinium enhancement MRI in a genetic model of arrhythmogenic atrial cardiomyopathy. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2014, 25, 964–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, K.K.; Dev, V.; Chopra, P.; Dave, T.H.; Radhakrishnan, S. Persistent atrial standstill--clinical, electrophysiological, and morphological study. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1991, 14, 1274–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazato, Y.; Nakata, Y.; Hisaoka, T.; Sumiyoshi, M.; Ogura, S.; Yamaguchi, H. Clinical and electrophysiological characteristics of atrial standstill. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1995, 18, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendy, F.N.; Bolognesi, R.; Bianchi, G.; Visioli, O. Alternation of partial and total atrial standstill. J. Electrocardiol. 1979, 12, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.; Pouget, B.; Bemurat, M.; Lacaze, J.C.; Clementy, J.; Bricaud, H. Partial atrial electrical standstill: Report of three cases and review of clinical and electrophysiological features. Eur. Heart J. 1980, 1, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewegen, W.A.; Firouzi, M.; Bezzina, C.R.; Vliex, S.; van Langen, I.M.; Sandkuijl, L.; Smits, J.P.; Hulsbeek, M.; Rook, M.B.; Jongsma, H.J.; et al. A cardiac sodium channel mutation cosegregates with a rare connexin40 genotype in familial atrial standstill. Circ. Res. 2003, 92, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goette, A.; Kalman, J.M.; Aguinaga, L.; Akar, J.; Cabrera, J.A.; Chen, S.A.; Chugh, S.S.; Corradi, D.; D’Avila, A.; Dobrev, D.; et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus on atrial cardiomyopathies: Definition, characterization, and clinical implication. Europace 2016, 18, 1455–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagura, L.; Porcari, A.; Cameli, M.; Biagini, E.; Canepa, M.; Crotti, L.; Imazio, M.; Forleo, C.; Pavasini, R.; Limongelli, G.; et al. ECG/echo indexes in the diagnostic approach to amyloid cardiomyopathy: A head-to-head comparison from the AC-TIVE study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 122, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, M.; Porcari, A.; Pagura, L.; Cameli, M.; Vergaro, G.; Musumeci, B.; Biagini, E.; Canepa, M.; Crotti, L.; Imazio, M.; et al. A national survey on prevalence of possible echocardiographic red flags of amyloid cardiomyopathy in consecutive patients undergoing routine echocardiography: Study design and patients characterization-the first insight from the AC-TIVE Study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 29, e173–e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guaricci, A.I.; Tarantini, G.; Basso, C.; Corbetti, F.; Rubino, M.; Ieva, R.; Daliento, L.; Gerosa, G.; Ramondo, A.; Thiene, G.; et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Giant aneurysm of the right atrial appendage in a 39-year-old woman. Circulation 2007, 115, e194–e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoun, M.A.; Toufayli, H.; Touma, M.J.; Nasr, S.R. Persistent Atrium Standstill Post Atrial Fibrillation Ablation Therapy. Cureus 2022, 14, e25293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottkamp, H.; Schreiber, D. The Substrate in “Early Persistent” Atrial Fibrillation: Arrhythmia Induced, Risk Factor Induced, or From a Specific Fibrotic Atrial Cardiomyopathy? JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2016, 2, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldo, A.L.; Vitikainen, K.J.; Kaiser, G.A.; Bowman, F.O., Jr.; Malm, J.R. Atrial standstill secondary to atrial inexcitability (atrial quiescence). Recognition and treatment following open-heart surgery. Circulation 1972, 46, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Volpato, V.; Cau, R.; Chiesa, M.; Saba, L.; Guglielmo, M.; Senatieri, A.; Chierchia, G.; Pontone, G.; Dell’Aversana, S.; et al. Application of AI in cardiovascular multimodality imaging. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Sciaccaluga, C.; Loiacono, F.; Simova, I.; Miglioranza, M.H.; Nistor, D.; Bandera, F.; Emdin, M.; Giannoni, A.; Ciccone, M.M.; et al. The analysis of left atrial function predicts the severity of functional impairment in chronic heart failure: The FLASH multicenter study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 286, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattel, S.; Burstein, B.; Dobrev, D. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: Mechanisms and implications. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2008, 1, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Fernandez, M.; Bueno Sen, A.; Cantolla Pablo, P.; Val Blasco, A.; Ruiz Hurtado, G.; Delgado, C.; Cubillos, C.; Bosca, L.; Fernandez Velasco, M. Atrial Myopathy and Heart Failure: Immunomolecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghamdi, B.; Hassan, W. Atrial Remodeling And Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanistic Interactions And Clinical Implications. J. Atr. Fibrillation 2009, 2, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Mishima, H.; Barc, J.; Takahashi, M.P.; Hirono, K.; Terada, S.; Kowase, S.; Sato, T.; Mukai, Y.; Yui, Y.; et al. Cardiac Emerinopathy: A Nonsyndromic Nuclear Envelopathy With Increased Risk of Thromboembolic Stroke Due to Progressive Atrial Standstill and Left Ventricular Noncompaction. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, e008712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretto, G.; Barison, A.; Forleo, C.; Di Resta, C.; Esposito, A.; Aquaro, G.D.; Scardapane, A.; Palmisano, A.; Emdin, M.; Resta, N.; et al. Late gadolinium enhancement role in arrhythmic risk stratification of patients with LMNA cardiomyopathy: Results from a long-term follow-up multicentre study. Europace 2020, 22, 1864–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forleo, C.; Carella, M.C.; Basile, P.; Carulli, E.; Dadamo, M.L.; Amati, F.; Loizzi, F.; Sorrentino, S.; Dentamaro, I.; Dicorato, M.M.; et al. Missense and Non-Missense Lamin A/C Gene Mutations Are Similarly Associated with Major Arrhythmic Cardiac Events: A 20-Year Single-Centre Experience. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, K.N.; Decker, J.A.; Friedman, R.A.; Kim, J.J. Homozygous mutation in SCN5A associated with atrial quiescence, recalcitrant arrhythmias, and poor capture thresholds. Heart Rhythm. 2011, 8, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takehara, N.; Makita, N.; Kawabe, J.; Sato, N.; Kawamura, Y.; Kitabatake, A.; Kikuchi, K. A cardiac sodium channel mutation identified in Brugada syndrome associated with atrial standstill. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 255, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.B.; Gando, I.; Bu, L.; Cecchin, F.; Coetzee, W. A homozygous SCN5A mutation associated with atrial standstill and sudden death. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2018, 41, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, W.P.; Sinagra, G.; Taylor, M.R.; Di Lenarda, A.; Ferguson, D.A.; Salcedo, E.E.; Slavov, D.; Zhu, X.; Caldwell, J.H.; Mestroni, L.; et al. SCN5A mutations associate with arrhythmic dilated cardiomyopathy and commonly localize to the voltage-sensing mechanism. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Riele, A.S.; Agullo-Pascual, E.; James, C.A.; Leo-Macias, A.; Cerrone, M.; Zhang, M.; Lin, X.; Lin, B.; Sobreira, N.L.; Amat-Alarcon, N.; et al. Multilevel analyses of SCN5A mutations in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy suggest non-canonical mechanisms for disease pathogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, A.A.M.; Amin, A.S. Clinical Spectrum of SCN5A Mutations: Long QT Syndrome, Brugada Syndrome, and Cardiomyopathy. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2018, 4, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makita, N.; Sasaki, K.; Groenewegen, W.A.; Yokota, T.; Yokoshiki, H.; Murakami, T.; Tsutsui, H. Congenital atrial standstill associated with coinheritance of a novel SCN5A mutation and connexin 40 polymorphisms. Heart Rhythm. 2005, 2, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Nozaki, Y.; Takahashi-Igari, M.; Sugano, M.; Makita, N.; Horigome, H. Progressive atrial myocardial fibrosis in a 4-year-old girl with atrial standstill associated with an SCN5A gene mutation. Hear. Case Rep. 2022, 8, 636–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, T.S.; Chiang, D.Y.; Ceresnak, S.R.; Ladouceur, V.B.; Whitehill, R.D.; Czosek, R.J.; Knilans, T.K.; Ahnfeldt, A.M.; Borresen, M.L.; Jaeggi, E.; et al. Atrial Standstill in the Pediatric Population: A Multi-Institution Collaboration. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 9, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuiyan, Z.A.; van den Berg, M.P.; van Tintelen, J.P.; Bink-Boelkens, M.T.; Wiesfeld, A.C.; Alders, M.; Postma, A.V.; van Langen, I.; Mannens, M.M.; Wilde, A.A. Expanding spectrum of human RYR2-related disease: New electrocardiographic, structural, and genetic features. Circulation 2007, 116, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollob, M.H. Expanding the Clinical Phenotype of Emerinopathies: Atrial Standstill and Left Ventricular Noncompaction. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, e009338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, N.; Arnaout, R.; Gula, L.J.; Spears, D.A.; Leong-Sit, P.; Li, Q.; Tarhuni, W.; Reischauer, S.; Chauhan, V.S.; Borkovich, M.; et al. A mutation in the atrial-specific myosin light chain gene (MYL4) causes familial atrial fibrillation. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Tang, K.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, H.; Li, D.; Yu, Y.; et al. Dysfunction of Myosin Light-Chain 4 (MYL4) Leads to Heritable Atrial Cardiomyopathy With Electrical, Contractile, and Structural Components: Evidence From Genetically-Engineered Rats. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e007030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson-Zingman, D.M.; Karst, M.L.; Zingman, L.V.; Heublein, D.M.; Darbar, D.; Herron, K.J.; Ballew, J.D.; de Andrade, M.; Burnett, J.C., Jr.; Olson, T.M. Atrial natriuretic peptide frameshift mutation in familial atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, P.M.; Fox, J.E.; Kim, R.; Rockman, H.A.; Kim, H.S.; Reddick, R.L.; Pandey, K.N.; Milgram, S.L.; Smithies, O.; Maeda, N. Hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and sudden death in mice lacking natriuretic peptide receptor A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 14730–14735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellaichamy, E.; Kaur, K.; Pandey, K.N. Enhanced activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in mice lacking natriuretic peptide receptor-A. Peptides 2007, 28, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McGrath, M.F.; de Bold, A.J. Determinants of natriuretic peptide gene expression. Peptides 2005, 26, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrudo, C.S.; Cavallero, S.; Rodriguez Fermepin, M.; Gonzalez, G.E.; Donato, M.; Kouyoumdzian, N.M.; Gelpi, R.J.; Hertig, C.M.; Choi, M.R.; Fernandez, B.E. Cardiac Natriuretic Peptide Profiles in Chronic Hypertension by Single or Sequentially Combined Renovascular and DOCA-Salt Treatments. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 651246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, M.; Rubattu, S. Editorial: Natriuretic Peptides in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 890158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vad, O.B.; van Vreeswijk, N.; Yassin, A.S.; Blaauw, Y.; Paludan-Muller, C.; Kanters, J.K.; Graff, C.; Schotten, U.; Benjamin, E.J.; Svendsen, J.H.; et al. Atrial cardiomyopathy: Markers and outcomes. Eur. Heart J. 2025, ehaf793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazelifar, A.F.; Arya, A.; Haghjoo, M.; Sadr-Ameli, M.A. Familial atrial standstill in association with dilated cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2005, 28, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaminisharif, A.; Shafiee, A.; Sahebjam, M.; Moezzi, A. Atrial standstill: A rare case. J. Tehran Heart Cent. 2011, 6, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Yang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Chen, Q.; Jin, Q. Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing in a Giant Atrium with Atrial Standstill: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 836964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Subtype | Etiology | Main Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary (Idiopathic) | Familial/Sporadic | SCN5A, NPPA, EMD, LMNA, MYL4, RYR2 | Biatrial, progressive, may be isolated |

| Secondary (Acquired) | Myocarditic, Infiltrative, Postsurgical | Amyloidosis, Ebstein’s anomaly, post-ablation, postoperative scarring | Partial or total, reversible or permanent |

| Neuromuscular | EDMD, muscular dystrophies | LMNA, EMD | Cardiac involvement may precede skeletal muscle manifestations |

| Gene | Protein | Pathogenic Mechanism | Inheritance Pattern | Phenotypic Features | Genotype–Phenotype Correlations Relevant to Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPPA | Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) | Reduced secretion and atrial fibrosis | Autosomal recessive | Biatrial, progressive, preserved ventricular function | Very high thromboembolic risk even without AF → early anticoagulation; regular imaging to monitor fibrotic progression |

| SCN5A | Sodium Voltage-Gated Channel Alpha Subunit 5 | Loss-of-function variants | Autosomal dominant or recessive | Atrial/ventricular arrhythmias, early-onset AS | Monitor for ventricular arrhythmias; anticipate device-implant challenges; consider anticoagulation when atrial capture is absent |

| EMD | Emerin | Nuclear envelope defect | X-linked recessive | AS with LVNC, thromboembolic strokes | Family screening; early anticoagulation; surveillance for LVNC and pacing issues |

| LMNA | Lamin A/C | Nuclear envelope defect | Autosomal dominant | AS in the context of laminopathy or DCM: high risk of ventricular arrhythmias, atrioventricular block, and sudden cardiac death | Close rhythm monitoring, frequent ECG Holters; low threshold for ICD due to malignant arrhythmic risk |

| MYL4 | Myosin light chain 4 | Impaired sarcomeric integrity | Autosomal dominant | Familial AF, progressive AS | Follow disease progression; evaluate for AF and loss of atrial mechanical function |

| RYR2 | Ryanodine receptor 2 | Abnormal calcium handling | Autosomal dominant | Catecholaminergic arrhythmias, sinoatrial and atrioventricular node dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, rare AS cases | Avoid adrenergic triggers; rhythm control; monitor for ventricular arrhythmias |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carella, M.C.; Dicorato, M.M.; Santobuono, V.E.; Dentamaro, I.; Basile, P.; Piccolo, S.; Labellarte, A.; Latorre, M.D.; Urgesi, E.; Pontone, G.; et al. Atrial Dilated Cardiomyopathy: From Molecular Pathogenesis to Clinical Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8773. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248773

Carella MC, Dicorato MM, Santobuono VE, Dentamaro I, Basile P, Piccolo S, Labellarte A, Latorre MD, Urgesi E, Pontone G, et al. Atrial Dilated Cardiomyopathy: From Molecular Pathogenesis to Clinical Implications. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8773. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248773

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarella, Maria Cristina, Marco Maria Dicorato, Vincenzo Ezio Santobuono, Ilaria Dentamaro, Paolo Basile, Stefania Piccolo, Antonio Labellarte, Michele Davide Latorre, Eduardo Urgesi, Gianluca Pontone, and et al. 2025. "Atrial Dilated Cardiomyopathy: From Molecular Pathogenesis to Clinical Implications" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8773. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248773

APA StyleCarella, M. C., Dicorato, M. M., Santobuono, V. E., Dentamaro, I., Basile, P., Piccolo, S., Labellarte, A., Latorre, M. D., Urgesi, E., Pontone, G., Resta, N., Arbustini, E., Ciccone, M. M., Guaricci, A. I., & Forleo, C. (2025). Atrial Dilated Cardiomyopathy: From Molecular Pathogenesis to Clinical Implications. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8773. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248773